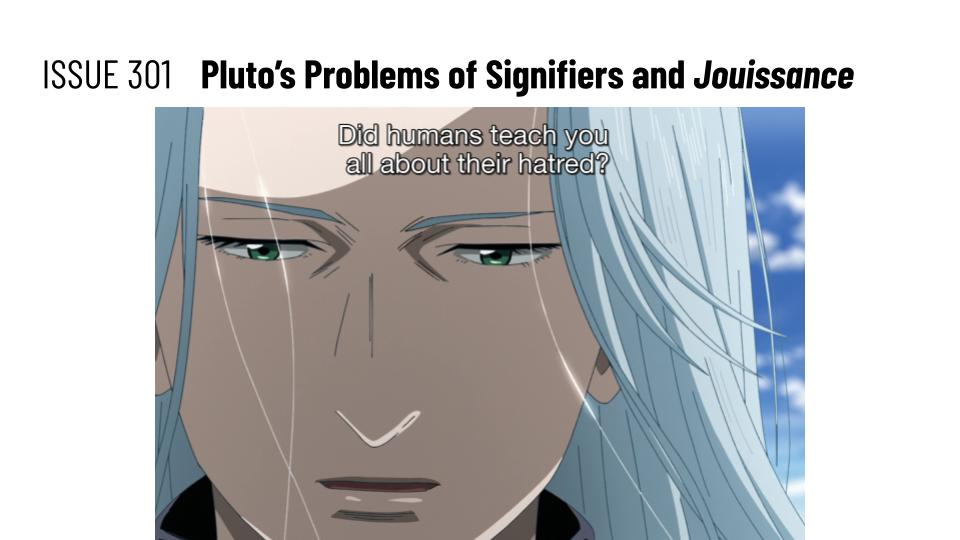

Issue #301: Pluto's Problems of Signifiers and Jouissance

Last week, I had a great time at my friend AJ’s screening of Drive (1997) at our local movie theater. Not the Ryan Gosling one. He gave Paradox Newsletter some much appreciated credit on the flyer, but I didn’t do anything other than help choose the date to my benefit. But, capitalizing on that generosity, I can say this was the second in a two film scr…