Issue #345: Understanding Jean-Pierre Melville's Late Period with No Context

This weekend, I rewatched Philadelphia (1993) and watched The Verdict (1982) for the first time. Philadelphia has one of the best Denzel Washington signature phrases and The Verdict, I learned, has an SSD flyer in it.

I’ve been meaning to watch Anatomy of a Murder (1959), and all three films are in the Criterion Channel’s courtroom dramas section.

I’m doing my background research in reverse, watching the films Anatomy of a Murder (probably) influenced to have a better grasp when I finally run it. But something stood out to me in both Philadelphia and The Verdict: business cards. I think business cards are actually more important to these movies than to American Psycho (2000).

In both Philadelphia and The Verdict, handing out a business cards signals the same things: desperation and moral degradation. The attorney who hands out his business card in a form of incessant advertisement is lacking in scruples, so follows from the logic of the film. But Philadelphia makes Denzel Washington’s Joe Miller look so damn cool soliciting personal injury cases.

By contrast, Paul Newman’s Frank Galvin is caught trying to drum up business at funerals.

In both films, though, the business card serves to flatten Miller and Galvin, with the added insult to Miller being referred to repeatedly as “the TV guy.” The flattened subject, the subject of business cards and legal proceedings, is a critical formulation for this genre of film. I’m not going to be putting any money on business cards being an important feature of Anatomy of a Murder, but I can only hope.

I shared out an event calendar last week, but I purposefully left out the most important one of all: the Medford citywide yard sale. I am participating both days. If you are in the area, I’ll be selling items related to various Paradox Newsletter topics. That means movies (yes, even ones directed by Hitchcock), t-shirts (mostly subcultural music shirts in size small and medium), sneakers, books, and sealed Magic: the Gathering product. Lots of stuff. If you would like to know exactly where this stuff will be, I recommend reaching out to me via Instagram: @outofsuit. This way it will be easier to tell who I am sharing my personal information with. Hope to see you there.

Finally, I have something a little extra for the paid subscribers at the end of the letter. It’s an experiment, but I hope you like it. If there’s anything that looks unusual, or this newsletter says “paid,” it’s not, really. The vast majority of the letter, the main stuff you expect, is available to all. But you’ll have to cop a paid subscription to read the inaugural Paradox Personal Shopper, below where the letter usually ends.

Capers and Critique: Late Style in Jean-Pierre Melville’s Un flic

Becoming One’s Own Notion

A couple weeks ago, I wrote about William Dean Howells. He has a very important quotation in “The Man of Letters as a Man of Business” (1893), one I quoted but was somewhat peripheral to my actual argument:

An author’s first book is too often not only his luckiest, but really his best; it has a brightness that dies out under the school he puts himself to, but a painter or sculptor is only the gainer by all the school he can give himself.

While I can’t speak too much for painting or sculpture, for writing, cinema, and music, I often find this to be all too true. I don’t think anyone would argue that the later works of Nietzsche, Henry James, or Sick of It All are better or more significant than what preceded them. There are some pretty obvious reasons why those artists would produce worse work, but I imagine whoever is reading this probably has plenty of examples who fit this trend. As a counterexample, the late Lacan is prized among scholars for its complexity, depth, and substance, with the work benefiting from the elimination of the guard rails of reputational uncertainty. There is something instructive about this idea, perhaps there’s an opposition between the “brightness” Howells describes and the confidence of an artist to produce something without any concern for the audience.

Though I am loathe to admit it, and I never would in conversation, Alfred Hitchcock may have an artistic trajectory more like Nietzsche than Lacan. Beginning with Marnie (1964), Hitchock’s final five films are of dubious quality, including Torn Curtain (1966), Topaz (1969), Frenzy (1972), and Family Plot (1976). While I think they are all good, and worth watching, Torn Curtain and Topaz stand out as relative lemons. But even Frenzy has a certain self-referential quality that renders it less powerful than Hitchcock’s work before 1964. It, more than any other film, elucidates the very nature of the late period, and suggests that the potential opposition between an appreciated and unappreciated final bunch of works may be less an issue of those works’ substance and quality and more an issue of their perception. With Frenzy, Hitchcock is evidently confronted with the challenge of retaining the essence of his work without repeating himself. Its weight, like the late Lacan, comes from being situated within a robust body of thought. The same could be said of the late Nietzsche or James, to account for the perception of its quality — though the same probably could not be argued of SOIA.

Discussing Hitchcock’s earliest work, Slavoj Žižek describes those films as “before he became his own notion” (Everything You Always… 3). Žižek alludes to Hegel in his usage of notion, referring back to Hegel’s enumeration of the notion or the concept in Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences Part I (1817). Hegel writes:

The Notion is the principle of freedom, the power of substance self-realised. It is a systematic whole, in which each of its constituent functions is the very total which the notion is, and is put as indissolubly one with it. Thus in its self-identity it has original and complete determinateness. (William Wallace trans.)

In the more recent Klaus Brinkmann and Daniel O. Dahlstrom translation, they use “concept” rather than “notion”:

The concept is the free, as the substantial power that is for itself, and it is the totality, since each of the moments in the whole that it is, and each is posited as an undivided unity with it. So, in its identity with itself, it is what is determinate in and for itself. (Brinkmann and Dahlstrom trans. 233)

Hegel suggests that his concept of the notion makes irrelevant the opposition between form and content:

As far as the opposition of form and content is concerned in this connection, namely, with respect to the concept as allegedly merely formal, this opposition, like all the other oppositions held fast by reflection, is already behind us as something overcome dialectically, that is to say through itself, and it is precisely the concept which contains all the earlier determinations of thinking as sublated determinations in itself. (Brinkmann and Dahlstrom trans. 233)

He goes on to say that the concept “contains the entire richness of these two spheres in an ideal unity” (Brinkmann and Dahlstrom trans. 233). When relating this to artistic style, particularly late style, the “notion” as Žižek uses it (or “concept” in later Hegel translations) serves to represent the apotheosis of a given style. It is determinate and ideal, the guarantor of the idea of style. When a work appears idiosyncratic to the “notion” of an artist, it can either transform that notion or be so distinct from it that it falls short of the ideal (in the Platonic sense, as Hegel intends) that it is rendered an aesthetic failure or assigned some other agency outside of that of the artist.

The formulation of the notion includes all the aspects of the object (as a specific philosophical formulation) Hegel outlines in the Phenomenology (1807) (Miller trans. 480). In The Encyclopedia, Hegel writes:

The concept as such contains the moments of universality (as the free sameness with itself in its determinacy), particularity (the determinacy in which the universal remains the same as itself, unalloyed), and individuality (as the reflection-in-itself of the determinacies of universality and particularity, the negative unity with itself that is the determinate in and for itself and at the same time identical with itself or universal). (Brinkmann and Dahlstrom trans. 236)

If the notion is so all-encompassing, it has a curious effect on artistic output that redirects critical attention from form and content to the notion as such. The notion has its own dialectical relationship with art, as art produces the notion, which in turn is the criterion by which art is judged — retroactively, contemporarily, and in the future. Such is the case in Žižek’s periodization of Hitchcock.

“I am in no way an author”

This idea of a determinate and guaranteeing notion, an ideal standard, must be an element of consideration for an artist in the late period. They react to their own notion, make it coherent or try to attack it. Whatever approach they take, the artist stands in their own shadow. Lacan actively resisted the idea of allowing a notion of his work to emerge as a coherent whole which could define his formal elements and the content of his theorization. In Lacan’s 1980 Caracas seminar, squarely within his late period, he began his remarks giving an account of his orientation, “It’s up to you to be Lacanians if you wish. For my part, I’m a Freudian” (Price trans.)

To the last, he rejected a notion of Lacan that would provide sense to the idea of “Lacanian,” asserting that he fits not within his own notion but that of Freud. Likewise, Lacan’s aversion to and critique of publishing culminates in the assertion that Lacan himself is not a Lacanian. He reflects on his formulation of poubellication (that I have written about several times) in Seminar XVI (2006)

[W]e must define the status of the discourse known as “psychoanalytic discourse,” whose emergence in our era entails so many consequences. A label has been placed on the way in which this discourse proceeds [le procés du discours]. “Structuralism,” it has been called — a term that did not require much ingenuity on the part of the publicist who suddenly coined it a few months ago, in order to emcompass a certain number of writers whose work had already long since sketched out several of the avenues of this discourse. I just mentioned a publicist. You are all aware of the play on words I have allowed myself around poubellication [a combination of poubelle (garbage can or rubbish bin) and publication…]. A certain number of us have thus been dumped into the same trash can thanks to he whose job it was to do so. I could have found myself in worse company. Indeed, I can hardly be uncomfortable about those with whom I find myself lumped, they being people for whose work I have the highest regard. (3)

There is a clear connection between the idea of poubellication and the specificity of a psychoanalytic discourse that is determinate and describable. Lacan throws that idea into question, however, suggesting that this discourse involves “statements [that] lie outside of meaning” (5). The following year, in Seminar XVII (1991), he would go on to give an account of Écrits (1966) that shows precisely why and how Lacan objects to the possibility of a notion emerging of his work:

I am in no way an author. Nobody even dreams of this when they read my Écrits. For a very long time this had remained carefully confined to an organ that had no other interest than to be as close as possible to what I am trying to define as calling knowledge into question. (191)

Hegel’s notion carries with it the knowledge of a person’s work that produces a certainty regarding what their ideal form is. Critics judge work relative to that ideal. But the work of the late period, “successful” or not, whether it is by James, Nietzsche, Hitchcock, or venerable NYHC bands, necessarily writhes against the constraints of the notion as an aesthetic ideal. Whether the work is seen as fitting within, expanding, subverting, rejecting, or ignoring the notion, this relation is impossible to avoid. Though Hegel may advance the idea as crucial for understanding the dialectical component of thought, Lacan’s phobia of being assimilated or sublimated into a notion of his own shows the risks of assuming one knows what an artist should express or how they should express it.

Indistinct Judgment and Diacritical Judgment

All of this puts me in a somewhat awkward position when evaluating the work that has, above all, inspired this train of thought: Jean-Pierre Melville’s Un flic (1972). Haden Guest, introducing the film, said it is considered “a relatively minor Melville,” which seemed to me a euphemism. Compared to Le deuxième souffle (1966), it is less organic. Un flic is both hewn to a sharp point and concretized within the notion of Melville. To that end, the question of Un flic that impresses itself upon me above all others is the question of late style. Un flic, especially the way I necessarily read it as only the second Melville I’ve seen, is in conversation with the idea of late style more than other texts.

Un flic may be a good movie — I think that it is — but it has another function as an object of criticism. Alain Badiou outlines the different avenues of critiquing a film:

There is a first way of talking about a film that consists in saying things like “I liked it” or “It didn’t grab me.” This stance is indistinct, since the rule of “liking” leaves its norm hidden. With reference to what expectation is judgment passed? … Let us call this first phase of speech “the indistinct judgment.” It concerns the indispensable exchange of opinions … There is a second way of talking about a film, which is precisely to defend it against the indistinct judgment. To show — which already requires the existence of some arguments — that the film in question cannot simply be placed in the space between pleasure and forgetting … The second species of judgment aims to designate a singularity whose emblem is the author … Let us call this judgment “the diacritical judgment.” It argues for the consideration of film as style. Style is what stands opposed to the indistinct. Linking the style to the author, the diacritical judgment proposes that something be salvaged from cinema, that cinema not be consigned to the forgetfulness of pleasures. (Cinema 94-95)

Reading Hegel into Badiou’s critical schema, the “diacritical judgment” intervenes specifically on the (Hegelian) notion of an author. The “indistinct judgment” may well use an author’s notion as the criterion for its judgment, but the ambiguity of the expression of “liking” leaves open the question of the evaluative system. Crucially, Badiou’s association of diacritical judgment to “salvag[ing] from cinema” a something that can’t be “consigned to the forgetfulness of pleasures” helps make sense of why an author’s notion is good for criticism. If we take Lacan’s claim seriously, though, such a notion is bad for art itself. Or, at least, a surmountable but unavoidable challenge every serious artist will eventually encounter.

With all of this in mind, I think it is also clear why an artist might make a work that intends primarily toward self-critique or deconstruction of one’s own notion, concept, ideal, take your pick. For Hitchcock, Frenzy is certainly that. As is The Golden Bowl (1904) for James. But for those authors, I’ve watched or read the majority of their oeuvre. For Melville, I can only judge Un flic against Le deuxième souffle.

Melville, Major and Minor

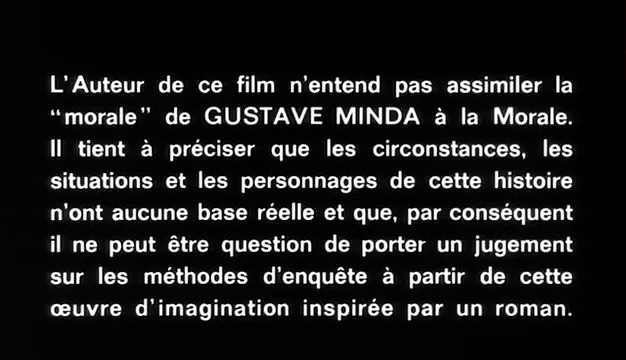

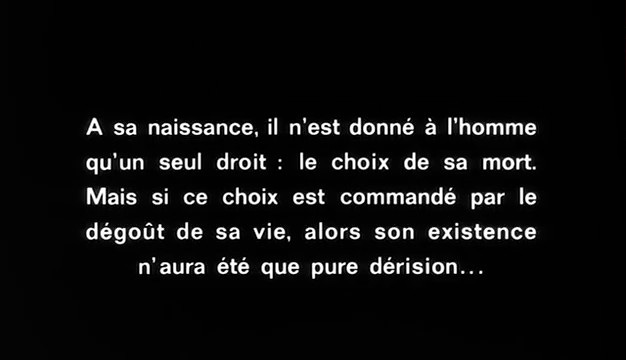

My examination of the two works begins with an ostensibly facile list of shared characteristics. Both films begin with some kind of epigraphic text card. In Le deuxième souffle:

It’s not the filmmaker’s intention to defend Gustave Minda’s ethical code. Persons and circumstances portrayed herein have no basis in fact and therefore no judgment is called for regarding the police methods portrayed in this work of fiction based on a novel.

A man is given but one right at birth: to choose his own death. But if he chooses because he’s weary of life, then his entire existence has been without meaning.

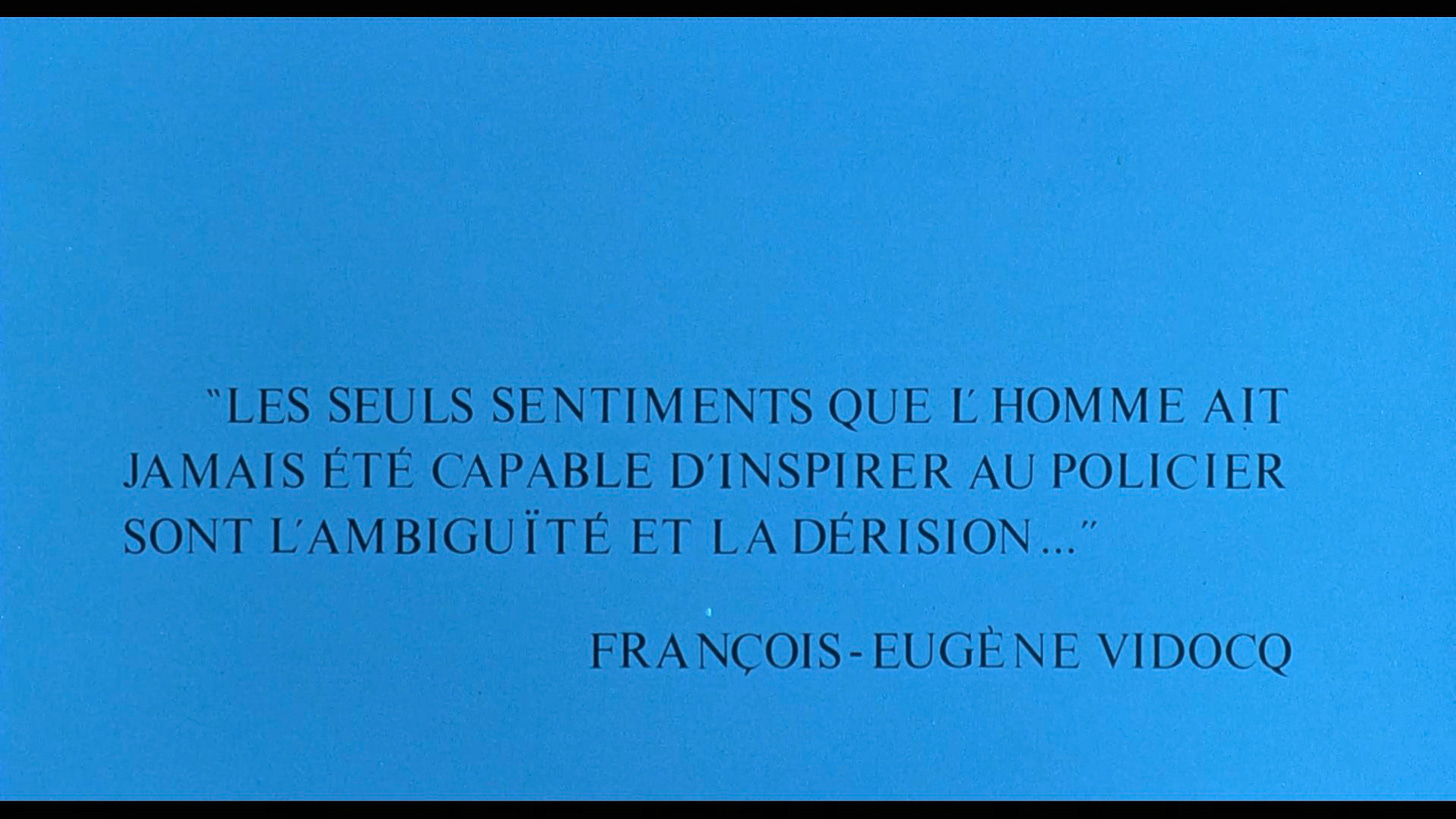

In Un flic, the epigraph is more brief, and attributed:

The only feelings mankind inspired in policemen are indifference and scorn

Unlike the steadiness of a text card, Melville’s camera can transform the realism of a scene into something bizarre and seemingly impossible, almost Escher-esque. Le deuxième souffle showcases this tendency right away, in the opening prison escape:

The dimensions of the space aren’t too unusual, but the position of the camera is disorienting and unsteady. Melville uses a ceiling mirror to similar effect in Un flic:

These are run-of-the-mill similarities, of course, along with the amoral or immoral police officers of Blot (Paul Meurisse) and Edouard Coleman (Alain Delon), the generic structure of the crime thriller film, and so on. But the text card opening and disorienting camera angles seem to me to demonstrate a similar kind of ambition. Even as the epigraphs appear to provide something one can hang their hat on, to say something definitive about the film that will follow, Melville then presents images that might elude coherent comprehension of the viewer.

This is at the level of plot, as well, with the hazily motivated Ricci family gunning for Gu (Lino Ventura) and his associates, then subsequently allying with them until that alliance is disrupted by a deception undertaken by Blot threatening Gu with reprisal by another crime boss, the Angel. Likewise, Mathieu (Léon Minisini) the heroin mule seemingly comes out of nowhere in Un flic to serve as yet another fixture to triangulate Coleman, Simon (Richard Crenna) and Cathy (Catherine Deneuve). In this case, Gaby (Valérie Wilson) is substituted for Cathy, as the one who knows something about Mathieu. But her knowledge can’t pass to Coleman, in turn causing Coleman to believe Gaby lied to him. The confrontation between Coleman and Gaby in the wake of the spectacular train robbery is where Un flic seems to disintegrate and distinguish itself from Le deuxième souffle. The cuts are more aggressive and the plot unfolds quickly. Le deuxième souffle never feels like anything but a tightly constructed work of film. Un flic’s climax and dénouement are like a spool of thread unraveling. In the film’s final moments, Coleman finds himself in the exact same spot, uttering the same words, as in the opening moments of the film.

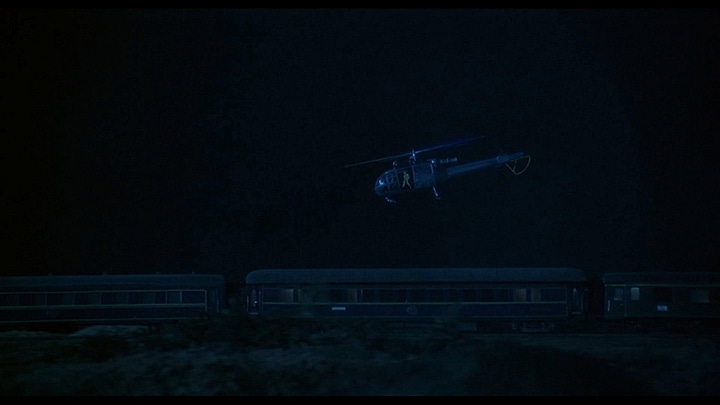

There’s a cyclical resolution to Un flic, but the film has the texture of anything but a circle. In the outrageous train robbery scene, Simon rappels from a helicopter to the top of a fast-moving train and climbs along it like Mission: Impossible (1996).

Un flic’s rough, explosive edges are the result, in my view, of a filmmaker attempting to escape the strictures of a definitive style. Le deuxième souffle is a character study of Gu and Blot, whereas Un flic seems, at times, totally disinterested in the interiority of its characters. Instead, it is fueled by the psycho-sexual relations in a triad of characters, two in direct opposition to one another and one serving as the switch point between them. What primes the pumps through which that symbolic fuel will flow is the idea that enforcement agents of the written law may contravene a greater Law, and there is honor among thieves who adhere to that Law more than the police (as was the case in Le deuxième souffle). But more than the earlier film, Un flic’s world is one where that line of separation, transgressed by both Coleman and Simon in their relationship with Cathy, is so thin it is nearly indiscernible.

In Melville’s case, William Dean Howells’ description of early and late style is right only by accident. Melville is not cowed by schooling or defanged by filmmaking norms. He, like many other artists, experienced a self-evident crisis in the confrontation with his own notion. Such a confrontation is what produced Un flic, as well as other messy, unforgettable works at the end of great artists’ period of productivity. Un flic might come across vastly different to me as I come to understand Melville’s work better, seeing more films through the series. But its unmistakable resemblance to the late work of Hitchcock and James makes evident Melville’s upheaval of himself.

Weekly Reading List

https://www.espn.com/sports-betting/story/_/id/41234480/congressmen-propose-new-federal-regulations-sports-betting — The current state of U.S. sports betting could be taught in a business school class called “How to Facilitate Widespread Industry Corruption.” It will be taught in history classes after the inevitable collapse of U.S. sport, crushed under the weight of massive and repeated gambling scandals, or economic collapse, whichever comes first. Media companies have financial stakes in sportsbooks and their commentators star in the commercials. Some even cut out the middleman and just work for the sportsbook, when you really don’t care about the appearance of impropriety. TV talking heads transparently make absurd predictions for a game’s outcome to stimulate a flaccid moneyline. Here’s a hint: if a TV network makes money when you bet, and all their commentators predict a team to win that Vegas odds have at +1000, that’s corruption.

When there is a supposed “scandal” with a sports player betting on themselves, their sport, whatever, the governing bodies and league executives look like surprised Pikachu. Players are subject to the most sports betting advertisement of all. They might as well be doing ad reads for it.

While there’s plenty I don’t agree with in this proposed legislation to create federal regulations for sports betting, this bit stands out to me:

If passed, the SAFE Bet act would prohibit gambling operators from running advertisements between the hours of 8 a.m. and 10 p.m. and during live sporting events.

I don’t care what time they air, but the prohibition of sports betting advertisements is a good start. It should also be illegal for a sports commentator to do sports betting commercials, work for a sports book, or bet themselves. Sports leagues and stadium owners should have no financial relationship with gambling operators. But none of this matters. Legislation like this will never, ever pass. There is way too much money in sports betting to put the guard rails on it that are needed to maintain the integrity of sports competition.

https://www.lacanonline.com/2024/09/news-august-2024/ — Owen Hewitson’s LacanOnline has posted its monthly news roundup for August. There’s a lot of great new Lacanian and psychoanalytic scholarship available, including Santanu Biswas’ The Major Literary Seminars of Jacques Lacan (2024) and the edited collection Towards the Limits of Freudian Thinking (2024), both of which I am reading right now. I am also anticipating Jean Allouch’s book, New Remarks on the Passage to the Act due out in English next year.

This youtube channel, Deadly Venoms, has been posting a treasure trove of NYHC videos I’ve never seen before.

I like videos that elucidate the samples used in popular music, and this one is full of some surprising hits like this one:

Until next time.

Except for paid subscribers, because the first edition of Paradox Personal Shopper is coming to you behind the paywall.