Issue #349: Authors Keeping Secrets from Themselves

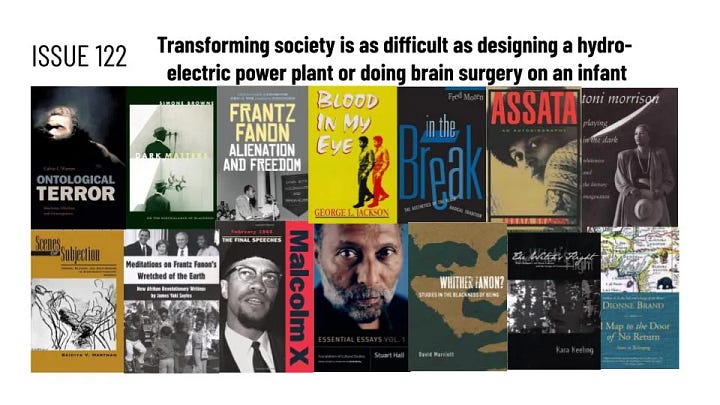

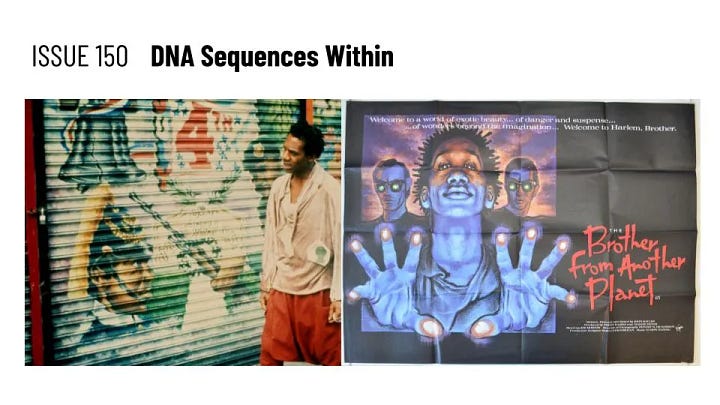

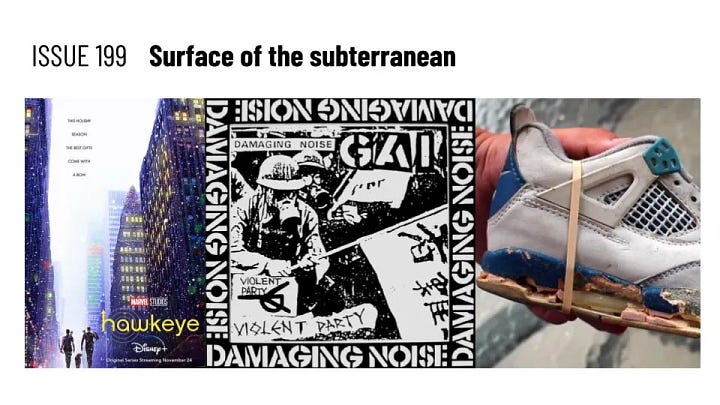

It should be obvious at this point that I am in a period of experimentation with my header images. Previously, I used a template Erin made for me in Google Slides. It’s the template I’ve used for 248 issues. That’s almost five years of Paradox Newsletter. I, obviously, thought it was good. But it’s had its ups and downs:

It had plenty of downsides. It wa…