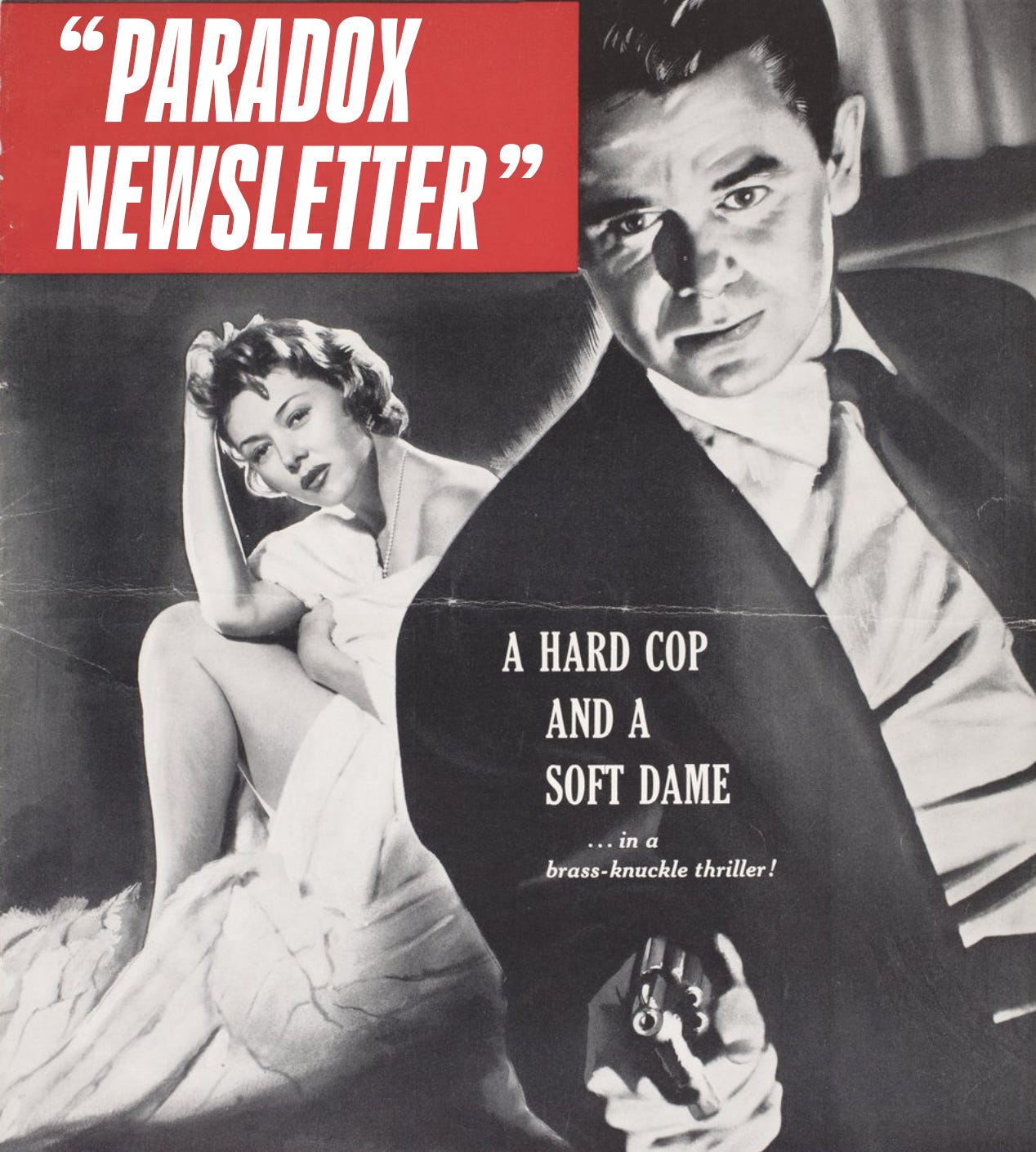

Issue #353: A Fritz Lang Double Feature Changed My Life

My birthday is on Friday. It’s a perfect time to buy a celebratory newsletter subscription with a birthday note.

I recently had an experience, celebrating someone else’s birthday, where they made a comment along the lines of “I’m not having any more after this.” The idea is that they are no longer aging, or no longer documenti…