Issue #368: Does Severance Think Women Are Enemies of Civilization?

This year’s LACK conference, the fifth in-person meeting since 2016, will be held at Otterbein University from March 13th until March 15th.

The preliminary schedule is available now and I encourage everyone who might be in the area to check it out. As of now I’ll be chairing and presenting on the “Classroom Subjects” panel, on Friday from 12pm to 1pm. Several friends of the letter will also be presenting:

My collaborators from the recent Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society special issue “Just a Game?”, Ryan Engley, Jack Black, and Joseph S. Reynoso present on topics related to the special issue on Thursday at 2pm

Clint Burnham and Rosemary Overell present on Thursday at 3:15pm, Burnham’s paper entitled “Reply-all: Beautiful Soul or Bartleby?” and Overell’s “Who is the Woman of the semblant? Post-MeToo feminism and the de Robertis incident”

Bright and early on Friday at 9:30am, Sheldon George will present “Race and the Vicissitudes of Jouissance”

On Saturday at 10:45am, Jared Pence presents “Total Destruction: Antigone and Aversions to Negativity”

All of these papers will be appointment viewing.

Speaking of appointment viewing, GQuuuuuuX (2025) is in U.S. theaters this week. I am going in with sky high expectations. If this film can meet or exceed them, I’ll probably write less about it than if it’s a disappointment.

This week I have a substantial Severance piece, complete with subheadings. The Discord will also be Severance-ing again this week. It’s never too late to join in.

I also review the new Captain America film. You think they’ll put me on Rotten Tomatoes?

Innies Inherit the Earth in Severance’s “Attila”

I want to begin with a Freudian digression, reflecting on this season of Severance (2022) as a whole. And why not? The show seems to upset the psychoanalytic paradigm of the gendered circulation of desire. Take, for instance, Jacques-Alain Miller’s reading of Civilization and its Discontents (1930) in “Of Women and Semblants” (1992):

Given the limited quantity of libido, what [men] give on one side, they have to withdraw from the other. Which is why Freud does not hesitate to make of women the enemies of civilization, which is to say the enemies of the semblants of civilization. He places them on the side of the real[.] (The Lacanian Review No. 13 Pg. 57)

A more contemporary, culturally savvy feminist view might accept enthusiastically Miller’s reading. Women as “the enemies of civilization” has the explosive, salacious quality of queer theory’s so-called anti-social turn in the late 90s and early 2000s. And, indeed, we have seen in repeated examples the opposition of woman to the notion of reproductive fecundity, as in Love Lies Bleeding (2024) and The Substance (2024).

To take this position to its most facile extreme and embrace the notion of “women’s wrongs” as the humorous reversal and resignification of “women’s rights,” one might read Helena as a sympathetic character: an amoral “girlboss” dedicated to the elevation of her status without sacrificing the whims of her wants and desires. In “Woe’s Hollow,” her knowledge gathering — in the realm of “corporate espionage” — included that of the biblical variety.

But I don’t think Severance lends itself very well to this reading, subverting the Freudo-Lacanian theoretical underpinnings I argue are essential to Love Lies Bleeding and The Substance. Instead, I feel compelled to look to Mark S’s (Adam Scott) refining of the Cold Harbor file. In “Trojan’s Horse,” Mr. Drummond (Darri Ólafsson) says Mark’s completion of the project “will be remembered as one of the greatest moments in the history of this planet.” What Mark does is contribute to the iteration of civilization, a moment that will follow in a series of corporate innovations from the personal computer to the iPhone to the procedure of severance itself. And what Mark requires to complete this task, in the logic of the show, is Helly R (Britt Lower). She is not literally necessary to the completion of the task, but Mark refuses to work without her to the extent that Lumon believes she is essential.

This structure makes Helly R and Helena allies of civilization rather than its opponents. But given the sinister character of Lumon and its activities — and the fact that the example of severance is a perfect one to show what their innovations share with the monkey’s paw — we will likely find that this next iteration of society that will be brought about by Cold Harbor’s refinement is not desirable.

Severance also makes clear Helly R/Helena is a distraction for Mark, albeit a necessary one if Lumon’s read of their dynamic is right. And what Helly might distract Mark from is not the refining, but the search for yet another woman, Gemma (Dichen Lachman).

This is an altogether more complex dynamic than the zero-sum expression of libido that Miller articulates, “what they give on one side, they have to withdraw from the other.” The font of Mark’s libido is also greater than that of a normal man. He is, after all, two men, unless of course the severing to bring this duality into existence involves “severing one’s balls” or castration.

The Headless Subject

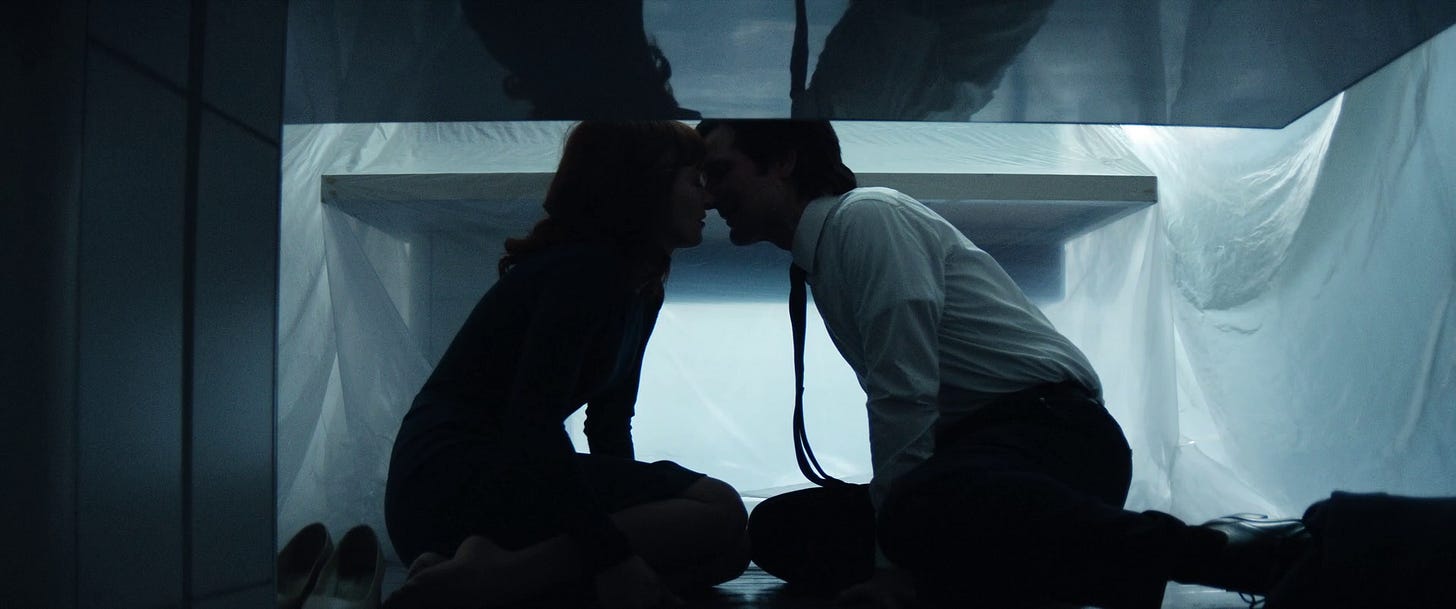

This lengthy preamble to my actual discussion of the episode is crucial to navigate the complex dynamic of gender in “Attila,” an episode with a sex act experienced by two separate subjects, Mark S and Mark Scout, over a remove of time. It is also an episode that speculates on the sex bodies may or may not be having without the knowledge of those that inhabit them. There are no shortage of evocative symbols in the course of exploring these (non-)relations, including that of the mirrored surface.

These mirrors are significant for more than just their symbolic value. In the bottom right image, of Milchick (Tramell Tillman) attempting to hew his diction down to the finest possible point, Eric Voss of New Rockstars points out that this is filmed practically. Instead of using a real mirror, Tillman stands on the side of a windowed cut out facing the camera with a body double facing away from the camera, giving the impression of a mirror.

This setup is necessary to avoid having to airbrush the camera’s reflection out of the image in post-production. Just another example of the impressive craft of Severance.

In the bottom left image of Mark S and Helly R under the table, there is the crucial detail of their missing heads in the upper reflection. They are always framed so their heads are absent, and as they get physically closer the reflection creates the illusion of two bodies attached to either side of their head.

The headless reflections evoke, to me, this bit from Jacques Lacan’s Seminar XI: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis (1973):

Do we not see in the Freudian metaphor the embodiment of this fundamental structure [the drive]—something that emerges from a rim, which redoubles its enclosed structure, following a course that returns, and of which nothing else ensures the consistency except the object, as something that must be circumvented.

This articulation leads us to make of the manifestation of the drive the mode of a headless subject, for everything is articulated in it in terms of tension, and has no relation to the subject other than one of topological community. (181)

Later, in the question and answer segment, Lacan answers Miller:

The object of the drive is to be situated at the level of what I have metaphorically called a headless subjectification, a subjectification without subject, a bone, a structure, an outline, which represents one side of the topology. The other side is that which is responsible for the fact that a subject, through his relations with the signifier, is a subject-with-holes. These holes came from somewhere. (184, emphasis added)

Let’s put aside the question of the so-emphasized subject-with-holes and what that might evoke about the back of Mark’s head or human anatomy. I promise I’ll come back to it.

In an attempt to simplify this provocative formulation from Lacan, one should know he is outlining both the function of the drive itself and the drive’s relation to human subjectivity. The drive’s trajectory is set by its necessary function: circulating around the drive’s object, the objet a. Lacan describes the subject acting in accordance with the drive as “headless,” the outline of a subject lacking its subjective contents. In terms of Severance corollaries, the moment of absolute disorientation between the consciousness of “outie” and “innie” may fit the bill.

What is even more important, however, is that this sexual encounter is every bit the bizarre ménage à trois referenced by Milchick in his character assassination of Harmony Cobel (Patricia Arquette). Mark Scout flashes back to the subjective experience of this encounter in the course of his reintegration. This is the headless subject par excellence, Mark Scout thrown into the experience of a sexual encounter that completely defies temporal sense logic. As Petey (Yul Vazquez) describes his sense experience during reintegration, “the relativity is fucked” (Severance S01E03, “In Perpetuity”).

Despite the reflection of the underside of the table, Mark S and Helly R aren’t headless subjects as Lacan describes. They decide to have sex because they want to, not at the behest of the drive.

It’s Mark Scout who is rendered driven by the drive, a subject-with-holes, as he seeks a fantasmatic wholeness that his reintegration will not provide, even if he manages to become one subject. Mark, both S and Scout, must pay the cost of undifferentiated jouissance to be subjects. Marcus André Vieira writes in “Love and Ravage” (2022):

Thus, since Freud, we have assumed that there is no way to recover lost jouissance, simply because this Eden never existed. This part of lost jouissance is irretrievable, not because we once ate the apple, but because it is precisely the part of ourselves to be lost for us to become people, to become the cultural beings that we are. (The Lacanian Review No. 13 Pg. 31)

Neither reintegrating his innie and outie, nor sex with Helly, nor finding Gemma will bring about this irretrievable wholeness.

Lacan’s formulation of the non-relation is that which cannot be bargained with and will always leave Mark S and Mark Scout unfulfilled — marked by the lack of his cranial cavity and the excess of the severance chip itself.

Being “like” a Head of the Company, or Being a Woman

Once again, Severance is unparalleled in its filming and staging of the HR-scandalizing sex scene between Mark S and Helly R. Their awkwardness demonstrates the imbalance between the two, Mark having his first sexual encounter with Helena during their ill-fated ORTBO and Helly having her first sexual encounter now.

The innies are infantilized, not simply by the Lumon jargon. They are children, coming into existence years or months ago, long after their corporeal body. Dylan G (Zach Cherry) showcases this infantile disposition meeting with his wife and Helly chafes against it remarking on how Helena “dresses [her] in the morning like [she’s] a baby.” The season one episode “In Perpetuity” also makes the connection through Petey, “my first day at Lumon's as far back as my fifth birthday.”

Perhaps the treatment of the innies as infantile corresponds to the material facts of the duration of their existence. But it is evocative, too, of the imperiled position women find themselves in relative to a masculinist society. Helena opening the possibility of her being a distraction, as she does in “Woe’s Hollow,” feeds into a quotidian misogyny that posits women as “distractions” in the workplace simply because of their presence. Helena seems to be navigating the complexity of being a woman in tech in many of the ways self-help books advise. She asserts her authority with a minor caveat, “like.” “Like” is only used as a verbal tic to punctuate her utterance, but we can also read into it the confession of a limit to her power because of her gender. It is the mark of the shortcoming others will perceive in her leadership, only present by virtue of being a woman rather than a cisgender man.

Contrasting the claim of authority, but in concert with the qualification, Helena also defers credit for the severance procedure — “Please, Mr. Severance is my father, I’m just Helena.” There is something misleading about this whole conversation. As Eric Voss points out in his recap, neither Helena nor James Eagan are likely to have been the scientific minds behind severance despite getting the credit for it, just as Steve Jobs is unlikely to have been the actual engineer or product designer who deserves the most credit for the iPhone and iOS. Nonetheless, the corporate head becomes a metonymy for the labor products of the entire company.

One might feel some compassion for Helena given the complexity of her gendered subject position, but the show won’t let the audience forget her villainy.

Helena, who unquestionably knows about Gemma given her status as “like, the head of the company,” is devious in her “accidental” misnaming. H and N are only separated by G and M by one letter of the alphabet, both incremented forward. Both substitutions also make the name closer to Helena’s as she attempts to supplant Gemma as the object of Mark’s affection. If there’s any question about the intentionality of this, one only need to refer to the subtitles’ specific spelling of “Hanna” without a concluding “H”, to match the number of letters in “Gemma.”

Bargaining for Business and Pleasure

This encounter between Mark Scout and Helena Eagan, the first of its kind, renews Mark’s commitment to the reintegration that should aid in Lumon’s downfall. The question becomes what exactly is Mark willing to give up in order to achieve his goal, and what will he actually need to give up?

Mark recounting bargaining to Asal Reghabi (Karen Aldridge) as “one of the stages,” leaving out the word “grief,” also evokes the act of bargaining in a business context. Many bargains are struck in the course of running a corporation like Lumon. Contracts between businesses and service providers and informal agreements with employees that promise pineapple bobbing and conjugal visits in exchange for continued labor.

Milchick’s Bargains

Milchick’s sequestration into a closet to perform a mixture of training and penance for his “contentions” is harrowing.

Milchick’s shaking hands make the paperclip training look unexpectedly brutal. And his transformation of his diction is unsettling with an undercurrent of humor, humor that alludes to another TV show with an office setting. As Milchick speaks, each iteration of his phrasing reduces the number of words he says. “You must eradicate from yourself childish folly” and “grow up” might be roughly equivalent sentiments, but he takes it too far when he reduces his utterance simply to “grow,” which he repeats over and over.

This is a form of malicious compliance, Milchick changing his manner of speech such that it follows Lumon’s instructions but becomes incoherent. The repeating “grow, grow, grow” also gives the word itself that uncanny quality of meaninglessness that comes when a word is said over and over.

A Perfectly Charming Dinner Party

The urbane Milchick might have been right at home as Burt (Christopher Walken) and Fields’s (John Noble) dinner guest. The pair talk with Irving (John Turturro) about “paint meant to evoke blood,” history, and theology. Their lengthy conversation intersects with many of the themes I’ve been exploring in my reading of Severance.

This theological reading of the severance procedure and the subjectivity of the outie and the innie corresponds to my reading of how the show positions its innie characters. But it also reverses the paradigm of the two. In life, the innie labors in a pristine white space meant to evoke hell — not heaven, despite its whiteness — while the outie experiences only the pleasures of the labor they know nothing about. This is, at least, the promise of severance. But the cost for this division is that in the eternal afterlife, the outie might find themselves experiencing undifferentiated unending suffering where the innie finally gets to partake of the pleasures of heaven. It’s the innie’s inheritance.

It’s no accident, too, that the question the Lutheran church answers is about how innie’s are morally judged rather than how they are morally considered, the latter of which is the realm of ethics and ontology. The contrast between the church and the Whole Mind Collective is precisely to draw out what’s missing in the church’s stance. They advocate only for the innie’s status in the afterlife, not the innie’s status as they reside on earth, an analogy to some of the shortcomings of organized religion when it comes to other kinds of liberation struggles. In 1837, Lutheran pastors needed to splinter into the Franckean Synod to break from the larger Lutheran church’s position on chattel slavery and advance abolitionist views.

I Need This Job like I Need a Hole in (the Back of) My Head

Political commentary about wage labor and the politics of organized religion is as substantial as the investigation of subjectivity Severance offers. But, it is that latter category to which I turn in delivering on my promise to talk about the hole in Mark’s head. Its presentation is rather gruesome, but this hole must be read in relation to the historical practice of trepanation.

In Hideo Yamamoto’s Homunculus (2003), protagonist Susumu Nakoshi undergoes a trepanation procedure that allows him to see “homunculi,” physical manifestation of psychic problems.

The hole drilling of the severance procedure works like this idealized version of trepanation, opening up a new kind of consciousness by virtue of a perforated skull. The hole really delivers on its trepanatory promise in Reghabi’s repurposing of it, to expand Mark’s consciousness by collapsing his innie and outie subjectivities.

Though it’s possible to perform trepanation safely, the hole in the head is most evocative of death. Indeed, reintegration means the possibility of death for Mark as an unintended consequence of the procedure — or as an intended consequence, its success putting an end to both Mark S and Mark Scout in its manifestation of a new conjoined consciousness.

Big Budget Freedom: A Review of Captain America: Brave New World

Whenever I think critically about a film from the Marvel Cinematic Universe, I can’t help but think about their entire cultural trajectory. Marvel movies make a fascinating case study. They went from critical darlings to routine punching bags from 2008 to today without too much qualitative change. The MCU output from 2021 onward is, on average, worse than its predecessors by any metric. That is difficult to deny. But I look at MCU movies as having a pretty low ceiling — and a low floor. Of the 35 feature films, I would only claim to really like six of them: Iron Man (2008), The Avengers (2012), Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014), Captain America: Civil War (2016), Avengers: Endgame (2019), and Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021). A few are inoffensive, but the vast majority of the remaining 29 have periods in their runtime where I thought to myself “this sucks.” As a result, I rarely revisit them, though I have a soft spot for Shang-Chi’s (2021) first 100 minutes. Without fail, I turn it off at the end. The concluding CGI clusterfuck epitomizes the kind of thing that makes MCU movies fall short in my book.

Marvel’s television spin-offs have been mostly failures. Like much of streaming television, Marvel Studios does not understand how to use 330 minutes of episodic storytelling. Even at its best — Loki (2021) and Hawkeye (2021) — the shows feel like long movies and fail to present coherent ideas or storytelling structure in their weekly serials.

But the pleasures of the MCU are unique relative to most other cinema. I value the brief moments of acting brilliance (Downey in Age of Ultron [2015] seeing the sprawled corpses of the Avengers), the pithy one-liners that fly under the radar of memeability and endless, obnoxious repetition, five minute conversation that can be dissected into unjustified philosophical analysis (Wyatt Russell’s John Walker and Clé Bennett’s Lemar Hoskins in episode four of The Falcon and the Winter Soldier [2021]), and the rare examples of practical action that are unmarred by the relentless cutting of the MCU editors.

Captain America: Brave New World (2025) is rich enough in these qualities, not quite reaching the level of me “really liking” it, but avoiding me ever thinking “this sucks.” I have a bias toward Captain America. He is a naive, ideological formation that presents the contrast between the realpolitik facts of the United States and the ideal of its symbols as meaningful. Captain America regularly opposes the edicts and authority of U.S. politics in both comics and cinema. Supposedly, Captain America represents what America really is as opposed to how it exists as a political entity.

This is not an unusual symbolic space. Any work where a figure subverts the authority they are meant to enforce opens up the possibility of loving the United States despite hating every political function it has ever carried out. Its an ideological invitation to remain invested in a collective despite opposition to the sum of that collective’s actions. Think film noir where the cop investigates what he’s not supposed to or spy films where the CIA/FBI/IMF operative ignores the chain of command to do the right thing, whatever that may be.

Julius Onah’s turn in the director’s chair is no different. Anthony Mackie’s Sam Wilson is set against Harrison Ford’s President Thaddeus Ross as a servant of the American people and opponent to the cohesion of hegemonic power. The individualist naïveté is relentless. But I don’t come to Marvel movies expecting to find their overarching themes satisfying or benevolent. Mackie has unmistakable charisma, carrying on the legacy of Chris Evans’ Steve Rogers. His recent performances in Altered Carbon (2020), The Falcon and the Winter Soldier, We Have a Ghost (2023), and Twisted Metal (2023), all utterly abysmal, had me convinced I misread his potential as the leading man of an action film. But Brave New World fully restores my confidence.

Conversations between Mackie and Carl Lumby as Isaiah Bradley and confrontations between he and Giancarlo Esposito as Seth Voelker are the dual fulcrums on which the movie turns. It is remarkably well constructed for a work that has supposedly been mangled in the editing room. The film called for an unprecedented twenty-two days of reshoots, nearly a quarter of the film’s 102 days of principal photography. Esposito’s Voelker is present in every act of the film despite being a new addition during the reshoots. It was a good decision. He’s a fantastic villain. Nothing in the film itself gives away the tumultuous production.

Brave New World does a great deal of work to sell the idea of an un-super-powered Sam Wilson as Captain America, drawing from the character’s cinematic history. The audience is repeatedly reminded of Wilson’s history as a VA counselor, calling back to one of Captain America 2’s more potent scenes. The film tells it more than it shows it, but Wilson seems like a former counselor when consoling Bradley, confronting Tim Blake Nelson’s Samuel Sterns, and talking down President Ross once he transforms into the gigantic Red Hulk. Wilson as the David to Red Hulk’s Goliath makes for a satisfying final act that doesn’t flinch from the reality of their power imbalance. Wilson can’t beat Red Hulk in a fight, so he has to find another means of triumph. And thank god the only thing that looks like shit in the movie’s climax is some 11th hour green screening — the only obvious evidence of the reshoots. The action is great, especially for what amounts to a fight between a stuntman and a cartoon that would make Zemeckis or Bakshi blush.

Among the MCU movies released since 2020, some, like Shang-Chi and Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022) have been unfairly maligned. They are largely interchangeable with any of the decent MCU films from its early era and have some exceptional bright spots. Others, like Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3 (2023) and Deadpool & Wolverine (2024) are overrated for all the reasons the majority of the MCU films are overrated — they’re piles of nothing without the kernels of quality on which I ground my enjoyment of these films. Brave New World will be among the former, a movie only slightly worse than the MCU’s best with some remarkable moments.

For Marvel movie fans, it’s worth seeing. And I can’t deny having profoundly low expectations for the film helped buoy it in my mind. But even with the lowest possible expectations, it has nothing to offer those who don’t remember what happened in 2014’s Captain America outing.

Weekly Reading List

This essay from Jessa Crispin is so good, I can only imagine the creative process behind it went something like this:

To continue the metaphor, she absolutely scorches the 2020 novel Rodham:

Published in 2020, after her loss of the 2016 election, Sittenfeld wanted to imagine a world in which Hillary could have won. But instead of happening on a Livejournal, where such cringe material is supposed to live, it came out in hardback from a major publisher. It is a pitiful, almost achingly sincere document, which makes it an interesting case study for understanding one aspect of woke culture, which was asking the audience to invest themselves imaginatively, emotionally, and financially in the elites.

I only wish I could have recommended this piece to people sooner.

https://mangadex.org/title/cddaf134-5f37-462c-a3d4-caf0c5c0f980/sanctuary — This is as much a recommendation to myself as it is to the readers. Sho Fumimura’s Sanctuary (1990) is so good. But I only got halfway through it before putting it down. This saga of collaborating yakuza crime lords and politicians deserves to be read as widely as possible.

Until next time.