Issue #372: Refining the Macrodata of the Severance Season Two Finale

Writing about Severance season two has been a delight. I started the weekly writing about it with a joke that it would increase my readership, but as it turned out, “engagement” with the newsletter has flagged significantly over this period of writing. That’s usually not the case when I take on a weekly topic — readership during these periods for Westworld (2016), Succession (2018), even Pluto (2023) tended to be above average. All of this is to say, those of you who are reading are in a smaller group than usual and you are commensurately appreciated for your engagement (not the algorithmic kind) with the work.

This is the end, so I’m meeting the text where I find it. I think every weekly write-up is focused on going wide, exploring connections across the breadth of the text, and not deep. This last one is no exception, and each individual essay might serve as the impetus for a more elaborate study later on. Hopefully no one holds the lack of depth against me.

Severance, particularly this second season, is a very rewarding text for doing the kind of analysis I like to do. I think, as a whole, it delivered on its promise and never let up on its ridiculous craftsmanship or flinched in reaching some provocative, but well earned, conclusions. I’m looking forward to the next season and will be excited to write about it again.

Once again, here are links back to the past essays:

“Hello, Ms. Cobel”: “Will Writing About Severance Spike My Newsletter Views This Week?”

“Goodbye, Mrs. Selvig”: “‘A Cure for Mankind’ in Severance’s ‘Goodbye, Mrs. Selvig’”

“Who Is Alive?”: “W. E. B. Du Bois and Frantz Fanon Take On ‘Inclusively Re-Canonized Paintings’”

“Attila”: “Innies Inherit the Earth in Severance’s ‘Attila’”

“The After Hours”: “‘I just got brain surgery in my basement’: Severance Seeking Balance in ‘The After Hours’”

A lot of people have been asking me to write about White Lotus (2021) season three, including some who I think tuned out for Severance. No promises, but I’ll at least watch an episode between now and next week.

I’m also continuing to update the Paradox Newsletter Spotify playlist. It has some good stuff on it right now.

Sanding Down the Edge of Human Subjectivity and Lumon’s Bureaucratic Incompetence in “Cold Harbor”

I could summarize this season, and really the show as a whole, as being about a lot of things. Antagonism, contradiction, the idea of a dialectic set against absolute negation. Class consciousness, wage labor, racial politics. What makes “us” human, religious zealotry, corporate incompetence and malice. I think Severance (2022) is about all these things. But really what I have come away with after thinking about the season for a few days is that it’s about community (which, fortunately, entails the other ideas I listed to varying degrees). I presented the overriding thought experiment of Severance as:

Would we condemn some other, derived but fundamentally disconnected, version of ourselves to a lifetime of endless rote and disquieting servitude if it meant never experiencing the banality of wage labor ourselves?

Now, I think the real thought experiment is “what do we owe to someone with whom we are inextricably connected but will never meet?”

Severance is, I think more than a lot of sci fi, deeply rooted in anxieties about U.S. electoral politics and civic functioning. But this question, it seems to me, is the one all of the characters are working to figure out more than any other in “Cold Harbor.” What obligation is shared between Mark S (Adam Scott) and Mark Scout? Helly (Britt Lower) and Helena? Despite its modest digression from the corporate intrigue, it’s Dylan’s (Zach Cherry) relationship with his innie that is most instructive here.

Each of our MDR innies exist on a continuum with regard to how they relate to their outie. For Dylan, he embraces a sort of mutuality that acknowledges what the innie and outie share. They seem to influence and change one another. This possibility of mutual transformation is, at least, what Dylan George imagines as a way the two can co-exist.

Making an analogy of this ideal to the Hegelian dialectic requires over-simplification and results in a somewhat weak analogy. Hegel’s dialectic is about ideas, not individual subjects. At the same time, I still find the movement from thesis to antithesis to synthesis as a relevant framework considered alongside Hegel’s treatment of contradiction. In The Science of Logic’s (1812) introduction, Hegel writes:

Dialectic, once considered a separate part of logic and, one may say, entirely misunderstood so far as its purpose and standpoint are concerned, thereby assumes a totally different position. – Even the Platonic dialectic, the Parmenides itself and elsewhere even more directly, on the one hand only has the aim of refuting limited assertions by internally dissolving them and, on the other hand, generally comes only to a negative result. Dialectic is commonly regarded as an external and negative activity which does not belong to the fact itself but is rooted in mere conceit, in a subjective obsession for subverting and bringing to naught everything firm and true, or at least as in resulting in nothing but the vanity of the subject matter subjected to dialectical treatment. (di Giovanni trans. 34-35)

With his critique of the Platonic dialectic, Hegel goes on to posit a dialectic that is neither external to thought nor something that “brings naught to everything firm and true,” — a negation. Hegel distinguishes his dialectical formulation following in the tradition of Kant, who he credits with giving “justification and credence” to “the necessity of the contradiction which belongs to the nature of thought determinations” (di Giovanni trans. 35). Hegel goes on, “The result, grasped in its positive aspect, is nothing else but the inner negativity of the determinations which is their self-moving soul, the principle of all natural and spiritual life” (di Giovanni trans. 35). If the antagonism between the outie and innie represent a thesis and antithesis, the resulting synthesis is not necessarily a reintegrated, non-contradictory individual, but a perpetuation of contradiction between the two subjects that results in their mutual transformation. This is quite different from the mutually exclusive intractable contradiction between Mark S and Mark Scout that the episode concludes with.

Reintegration is scary, and neither Mark S, Mark Scout, nor even Cobel (Patricia Arquette) can explain how it works. It’s an operation that smooths out and flattens contradiction, something the mutual acknowledgement between Dylan G and Dylan George retains. Dylan George wants to be changed by his innie’s very existence as opposed to the collapsing of the two into one. It is, in fact, Dylan George’s strong belief that the two are separate that makes their mutual recognition possible. This antagonism or contradiction is found on a recognition Mark Scout doesn’t offer to Mark S. One can read into this the Fanonian revision of Hegel’s dialectic, contingent on one party disputing the ethical and ontological status of the other — the innie isn’t “real,” their love pales in comparison to the love Mark Scout has for Gemma (Dichen Lachman).

Helly, who has up until now represented the most incompatible orientation of an innie toward an outie, comes to embody the middle of the spectrum in simple acknowledgement of her relationship to Helena: “I’m her.” She comes to realize this through Jame Eagan’s (Michael Siberry) fetishistic view of her. Eagan sees in Helly what he once saw in Helena, pointing Helly to an underlying similarity she can’t deny.

As I alluded to above, Mark is the one who somewhat unexpectedly comes to represent the absolute negation of the other. In the case of reintegration, each could be assenting to the elimination of the other in the forming of the new combined person. But more than that, he’s the only character who gets to argue between innie and outie, face to face, in as close to real time as possible. They don’t trust each other. And Mark Scout doesn’t acknowledge or respect the love and experience that Mark S values.

If the synthesis modeled by Dylan G/eorge is actually one that retains the liberal ideal of venerating one’s difference, Mark S/cout’s antagonism is absolute. It culminates not in their combination into one, another form of synthesis, but a negation. One must kill the other in order to live the life they demand. They follow the model of the betta fish Mark keeps, their imposing barrier always representing the impossibility of coexistence.

As Severance continues, I’m sure we’ll see different conditions under which each kind of relationship between outie and innie is more or less possible or tenable. But Mark’s shared hostility seized both by his outie and innie evokes the aggression one feels to their specular image in Lacan’s mirror stage. Jacques-Alain Miller writes:

To say that one always kills one’s closest neighbor, means to say: one kills oneself. It is the to kill [TN: tuer, to kill/tu es, you are] in so far as he is reduced to the mirror stage. (”Some Remarks on the Logic of War” 90)

Dylan G embraces the love of the closest neighbor, the outie, while Mark S resolves to kill that neighbor lest he be killed himself.

Dylan George also introduces an idea critical to the entire episode and the broader philosophical apparatus of what defines the outie, innie, and their relationship to one another: shared physiology.

In the throwaway account of why Dylan G may love Gretchen (Merritt Wever) to the same degree as Dylan George, it also contrasts Dylan G to Mark S. Mark S, of course, doesn’t feel the love for Gemma that so compels Mark Scout. He looks at her on the other side of the severance barrier, in the stairwell, and feels nothing. This, too, demonstrates just what it takes for an innie to be severed from the powerful emotions of their outie. It requires their own deep feeling and emotion, not an excision of emotion of “taming of the tempers” as Lumon fails to do with Gemma’s twenty-fifth “Cold Harbor” innie.

Successes and Failures of a Bureaucratic Cult

What innies and outies are to one another will be the constant meditation of this show, but one question I felt was satisfactorily answered by the episode is the nature of Lumon’s test. In Kier’s “eternal war against pain,” Lumon seeks to confront Gemma with what they view as her most traumatic memory and determine whether or not she has any emotional response as a result.

There are several, obvious problems with Lumon’s testing framework. The test itself seems a bit anticlimactic when compared to the detailed setting or implicit technological complexity of subjecting Gemma to writing three hundred thank you cards on Christmas morning or an ongoing plane crash. These situations, regardless of one’s taste for writing thank you cards or airplane turbulence, are unpleasant, physically taxing, and threatening. Disassembling a piece of furniture inherently presents no such emotional or physiological challenge. Even more confounding, Gemma is not the one who disassembled the crib in the recollections of “Chikhai Bardo.” When Dr. Mauer (Robby Benson) remarks with glee, “she feels nothing” watching Gemma, I can only answer “no shit.” The scope of this test is totally insufficient to produce a meaningful result for what they set out to test in the first place — can Gemma do something unpleasant (to her, specifically) without having an emotional response?

Of course, she does seem to have an emotional response to Mark’s entry into the room, and this also clearly enough evinces the test’s failure as Mauer and Jame only seem to become concerned after Gemma responds to Mark’s pleas that she leave with him. This entire ridiculous scenario is illustrative of the broader point that Lumon does not know what they are doing, controlled only by corporate hubris and cultish zealotry, tests on severance being run without the consultation of the very person who invented it.

This is the Wizard of Oz twist of “Cold Harbor,” “the most important day in human history” transformed into just another “revolving” that changes nothing about society and only brings Kier’s “grand agendum nearer to fulfillment.” The idea of this as simply one small step for Lumon and no leap at all for mankind is a total reversal of the promised significance of the Cold Harbor file. And yet, Lumon proceeds with the pomp and circumstance with little justification other than their own self-congratulation and mythologizing.

Lumon may be, perhaps, the first evil corporation in sci-fi history that is as stupid and inefficient as the average real life counterpart. Even as there is some ambiguity regarding how to read both the efficacy and sense of Lumon’s Cold Harbor test, the episode unquestionably pulls back the curtain on the cultish nonsense logic that governs Lumon. While there has been a great deal of speculation about the purpose and function of the goats, it turns out they are an run-of-the-mill ritual animal sacrifice.

The “grand agendum” of Kier, according to this episode, is far less spectacular and epoch-defining than one might have speculated. This kind of subversion mirrors both the logic of The Wizard of Oz and even presents a compelling corollary between the symbolism of “Cold Harbor” and “Rosebud” in Citizen Kane.

Lumon nonsense, the drive of Drummond

Lumon is ultimately a less imposing conspiratorial master than they first appeared, burdening their bureaucracy with meaningless ritual and questionable science even by the show’s own loose, fictional standards. But Lumon as a site of nonsense is critical as it relates to the nonsense of drive essential to the human subject. The show is very thoughtful about this, aligning Drummond (Ólafur Darri Ólafsson) with No Country for Old Men’s (2007) Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem) by their shared use of a captive bolt pistol and similar haircut.

As Lumon seeks to “tame the tempers,” defeat Gemma’s pain, and eliminate from her all affect through aggressive, repeated severance, it cannot even excise from itself the excesses of humanity that regulate its function. These excesses are manifest in the non-words like “agendum” and deeply strange company diction. Helly and Jame’s conversation draws out most emphatically the disjunction between Lumon’s mode of speech and normal sense.

Even if Lumon could be successful at sanding down the edges of human subjectivity, this form of derelict subjectivity would not produce their desired result: a subservient, controllable work force.

The space of the Lumon building assuredly has as-yet unexplored horizons, perhaps fitting the bill of the “building that’s, like, so big that it became a continent.”

“Cold Harbor” expands that inner universe with Choreography and Merriment, the marching band that becomes Helly’s insurgent innie army.

The marching band performance and Vaudeville act are important to the logic of race in Severance, inviting further consideration of the innie analogy to colonized, oppressed, and enslaved people. Vaudeville has its obvious genealogical connection with minstrelsy, but Tramell Tillman discusses the specific attenuation of the marching band performances in the TV Insider “Severance Aftershow”:

There’s a stark transition between the introduction of the Kier Hymn and the Ballad of Gunnel and Ambrose, right? I think it’s not for naught, and I’m so glad that Ben [Stiller] listened to my suggestion on this, where the Kier Hymn was very traditional. It’s a military style. And then we have this ballad and this ballad allows Milchick to let loose.And we see this band adopt this HBCU, you know, flavor and they’re having fun and getting down on the severed floor. And I believe that is an indication of Milchick finding himself in the midst of this company and where he fits in this company, if he fits at all.

Adding to the scene’s texture, Stiller himself named Citizen Kane and Drumline (2002) as influences on the scene.

All of this culminates with Helly’s rallying cry that invites these alienated innies to unite on the basis of their shared experience.

In Severance, the class consciousness that arises among the innies is not based on a shared economic position but rather a shared peril, a universalized particularity that can cause a group to cohere. Their conscious demand and unconscious desire, ultimately to “feel whole” under very specific conditions, are what turns the individuals into the group and makes more immediate that shared obligation to one another. In other words, Helly is creating a community.

Lumon’s entire project is a mistake according to the same logic as Mark Scout’s, the logic that treats the innie as less than according to the brevity and contingency of their existence. But Mark S is the one ultimately able to abandon his external un-lived life outside of the Lumon building, not Gemma for whom a successful Cold Harbor test would have been to feel nothing. It is precisely because Mark S does feel something, something he believes is as strong as Mark Scout’s feelings, that he is able to sever himself from the “shared physiology” that makes Dylan G and Dylan George love the same woman.

In this light, Milchick is perhaps the most effective — and sinister — middle manager in Lumon history, cultivating his “kindness reforms” that appeal to the innies’ sense of humanity and familiarity with one another. Mark S seeks to perpetuate his existence at tremendous cost because of the community, or family, he finds within the confines of the severed floor. One may cynically read this as the same kind of ideological valorization of wage labor as in something like The Office (2005). But it also highlights something like fortitude or resilience, and the methods through which the intrinsic resistance to crushing force comes from a desire that one should never relinquish.

What Severance shows, too, is any prescriptive advice of not giving ground relative to one’s desire is redundant. One can never evade desire’s circulation, it is only a question of what it is oriented toward. Lumon seeks to obliterate the immutable, ignorant of the reality that from birth, innie or outie, one is never whole.

Weekly Reading List

Appropos of nothing, I was exploring the geography and sociology of Calgary, Alberta, Canada. This led me to the jurisdiction of Blood 148 and the Blood First Nation, which, in turn, led me to this very interesting documentary.

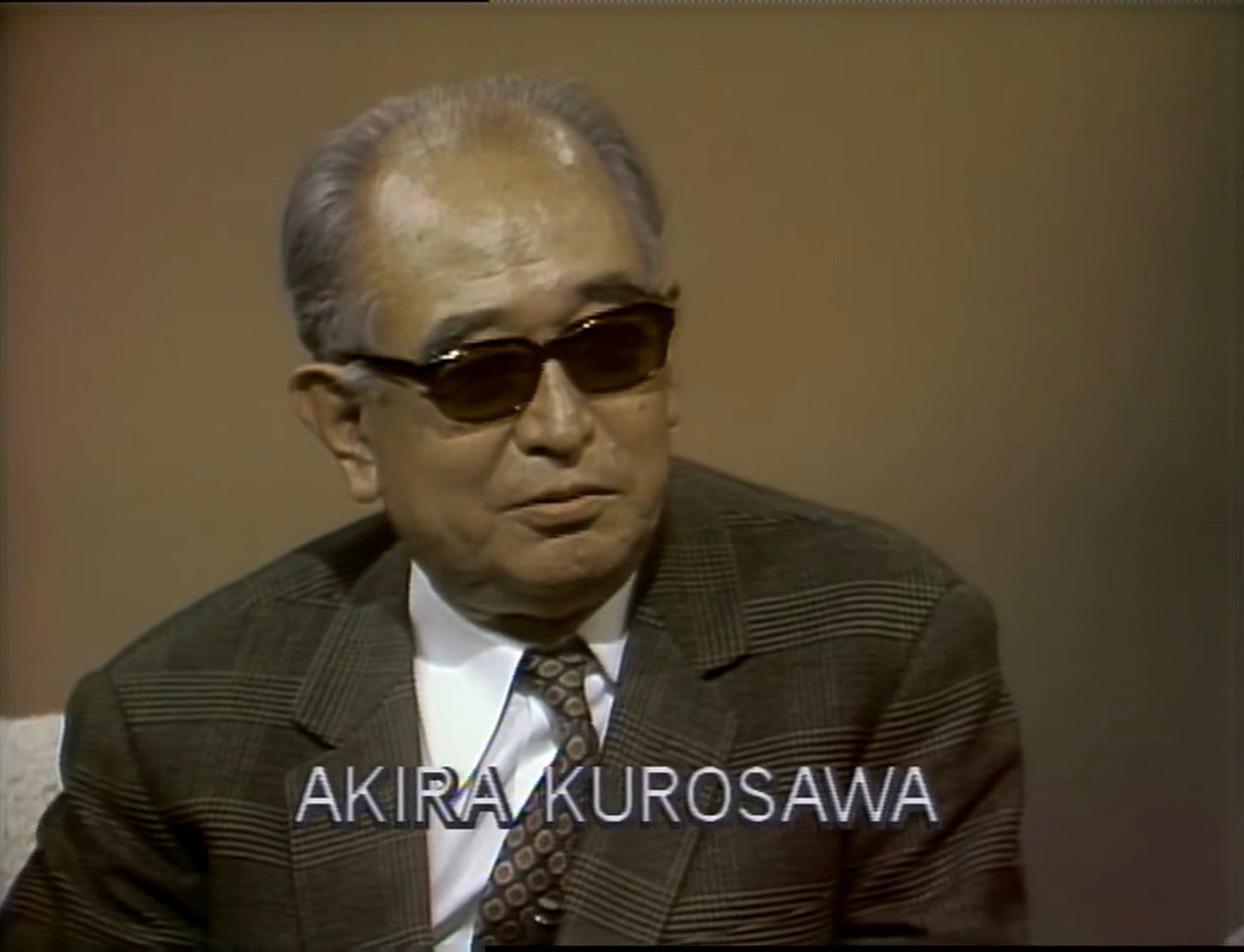

Akira Kurosawa on Dick Cavett. Need I say more?

The history of Sonic video games is inextricably connected to U.S. pop and R&B. These are some pretty interesting resonances.

Until next time.