Issue #373: Grabbing on The White Lotus's Endless Karmic Cycle

This week, I have been thinking a lot about the cultural phenomenon of Linsanity. I even watched a documentary about it from 2013. It was pretty good, but a little bit immediate. I would have appreciated something with some distance. Jeremy Lin did win a championship with Toronto in 2019, after all. In addition to the remarkable confluence of events that put Lin on the map and the incredible significance of his success to various groups, there’s also a story about perseverence and belief. These things are important for anyone trying to achieve anything.

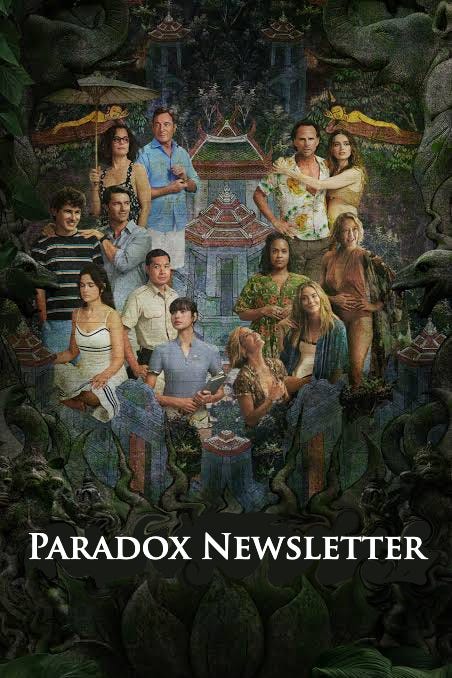

What I achieved this past week is getting caught up on The White Lotus’s third season. Now I am all up to date. I have a litany of screenshots and notes that will hopefully transform into writing projects. This week, I’m just getting my feet wet. But Frank’s monologue is undeniable television history, so that is part of the focus.

Minor spoilers for the first seven episodes of The White Lotus season three follow, but I don’t really discuss major plot points beyond “Full-Moon Party.” Either way, if you’re this far in, you might as well get caught up before reading.

“Maybe I can still get some satisfaction”: Desire and The Pleasure Principle in The White Lotus

Lacanian Super Predators and the Lacan-issance

The White Lotus’s (2021) third season third episode is entitled “The Meaning of Dreams,” one word off from the English translation of Freud’s essential work, The Interpretation of Dreams (1899). The difference between “interpretation” and “meaning” is critical here. Piper Ratliff (Sarah Catherine Hook) tries to explicate her mother’s (Parker Posey as Victoria Ratliff) dream at the breakfast table:

I could try to tell you what they mean … every symbol has a meaning. It’s the collective unconscious.

But this episode, and this season of The White Lotus as a whole, stages a missed encounter between itself and Lacanian psychoanalysis. Mike White’s series is notable for Lacan’s appearance in the text; in the first season, Olivia Mossbacher (Sydney Sweeney) reads Lacan’s Écrits (1977) in the airport. One imagines, however, that this work could have been any large, urbane work of theory or continental philosophy. In the text, it is essentially gibberish that signifies a comedic point of Mossbacher’s own self-important intellectualism that divorces her from reality.

Accordingly, this presence of Lacan in The White Lotus has transformed his work into another form of intellectual signaling (as opposed to virtue signaling) gibberish — one might read this inscription of Lacan in the culture as lalangue. Some provocative idiot on twitter coined the phrase “Lacanian super predator,” with no ostensible or legible meaning, because of the simple fact Sweeney the actress was on screen with Écrits. Instead of cultural criticism, they were doing free association.

To bathe the phrase “Lacanian super predator” in the font of knowledge would be to divorce it from its vague relation to a feminine archetype and understand that it is Lacan’s intellectual legacy that is itself the predator, threatening to subsume lines of thinking under the robust and rich contours of his theorization. This is the risk of my own writing about a text. Mike White, not a theorist but an artist, has created vivid and vital (as it relates to life, not as it relates to necessity) work. I endeavor to read it under the auspices of Lacanian theory without flattening it, lest I become a Lacanian super predator myself.

There’s no need for Mike White to be entirely in lockstep with Lacanian theory as a precondition for thinking The White Lotus with Lacan. Take Piper’s view of dreams. “Every symbol has a meaning” would be the precise opposite of the Freudo-Lacanian view of dream interpretation. In Seminar VI, Desire and Its Interpretation (2013) Lacan writes:

Let me summarize. The subject’s situation at the level of the unconscious, such as Freud articulates it — and it is not me but rather Freud who says this — is that he does not know with what he is speaking. We must thus reveal to him the properly signifying elements of his discourse. Nor does he know the message that really comes back to him at the level of the being’s discourse [du discours de l’être] — let us say “truly,” if you prefer, but I will not take back “really.” In other words, the subject does not know the message that comes back to him from the response to his demand in the field of what he wants. But you already know the answer, the true response. There can only be one. Namely, the signifier, and nothing but it, that is especially designed to designate the relations between the subject and the signifier [or: signifying system as a whole, le signifiant]. This signifier is the phallus, and I have already told you why. I ask those who are hearing this for the first time to accept it provisionally. This is not the point; the point is that the subject cannot have the answer [réponse], because the only answer is the signifier that designates his relations with the signifier. The subject annihilates himself and disappears to the degree that he articulates this answer. This is what makes it such that the only thing he can sense about it is a threat directly targeting the phallus — namely, castration, or the notion of the lack of the phallus, which is what the termination of analysis revolves around in both sexes, as Freud formulated it and as I am pointing out. But my goal is not to repeat such elementary truths. (35)

If you are the type of reader whose eyes glaze over when I quote long passages of Lacan, as I assume most are, I implore you to read this one closely — but only so closely such that you find my reading compelling. There are a number of Lacan’s quirks on display: his reverence to Freud, his tendency to “summarize” at length and term complex, unique readings as “elementary truths.” As it relates to extracting meaning from the unconscious, Lacan posits here that the meaning only exists to the extent that there is signification. In other words, every symbol doesn’t have a meaning, but rather in its eruption from the unconscious performs a signifying operation that positions the subject in relation to the phallus — the ultimate signifier-without-meaning. In turn, the subject’s relationship to other signifiers follows this structure.

Slavoj Žižek offers a complementary reading of Freudian dream interpretation in The Sublime Object of Ideology (1989):

This is why we should not reduce the interpretation of dreams, or symptoms in general, to the retranslation of the ‘latent dream-thought’ into the ‘normal’, every day common language of inter-subjective communication … [unconscious desire] is therefore not ‘more concealed, deeper’ in relation to the latent thought, it is decidedly more ‘on the surface’, consisting entirely of the signifier’s mechanisms, of the treatment to which the latent thought is submitted. In other words, its only place is in the form of the ‘dream’: the real subject matter of the dream (unconscious desire articulates itself in the dream-work, in the elaboration of its ‘latent content’ (5-6)

Žižek goes on:

even after we have explained its hidden meaning, its latent thought, the dream remains an enigmatic phenomenon; what is not yet explained is simply its form, the process by means of which the hidden meaning disguised itself in such a form. (8)

In other words, it is how something signifies in a dream rather than what it signifies that is the space upon which psychoanalysis can intervene. There’s a corollary to artistic production, too. During the production of the show Michelle Monaghan, who plays the actress Jaclyn Lemon, asked Mike White about the nature of the show Jaclyn stars in. Monaghan recalls the conversation with White, “Mike made a conscious choice … not to decide what [the show] was. And he didn’t want me to decide what it was either.” Following the analogy, then, it is clear that the concrete facts of a character are less important than their structural position — Jaclyn is a famous TV actress, it doesn’t matter what she’s famous for. Likewise, the hidden meanings of the dream are less important than the form the dream takes and the ways the subject is related to the signifier through their unconscious desire.

The White Lotus’s Dark Comedy of Manners

The White Lotus is also a productive intertext with 19th Century American novels. Henry James, Edith Wharton, and Theodore Dreiser explore the same sort of ideas that fascinate White. There are echoes of Frank Cowperwood from Dreiser’s The Financier (1912) in Tim Ratliff (Jason Isaacs). The White Lotus never loses sight of where the action is. Both the set piece robbery in “Special Treatments” and the snake liberation in “The Meaning of Dreams” pale in comparison to the tension of the dinnertime and bedroom conversations that follow the events.

The season begins with more bombast than the average 19th Century novel, though, with a shooting at the White Lotus resort in Ko Samui, Thailand. As the season has progressed, there are a lot of candidates for the shooter. Tim Ratliff, his son Saxon (Patrick Schwarzenegger), Gaitok (Tayme Thapthimthong), Rick Hatchett (Walton Goggins), Laurie Duffy (Carrie Coon), or even Jaclyn Lemon (Michelle Monaghan) seem poised for the kind of abrupt, chaotic breakdown that could conceivably result in waving a gun around the resort. This is to say nothing of Greg Hunt (Jon Gries), who lives in a house fit for a criminal mastermind. Of course, we also know that The White Lotus often subverts expectations, and the circumstances that lead to the series’s opening scene could be less catastrophic or intentional than one might assume.

According to producer David Bernad, this season came to Mike White in the course of a nebulizer hallucination to treat bronchitis. This season of The White Lotus, then, may be well-suited for the same kind of interpretation as that to which one might subject a dream.

Desire and Form

In The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis (1973), Lacan calls Freud’s knowledge of the unconscious “indestructible” and capable of “support[ing] an interrogation which, up to the present day, has never been exhausted” (232). Mike White’s monologue written for Frank (Sam Rockwell) in “Full-Moon Party” seems to be an equivalent text, indestructible and inexhaustible in its richness. Frank discusses a very specific kind of sexual encounter he stages, involving dressing like a woman and having sex with another man who looks similar to him all while being watched by an Asian woman.

He explains his reasoning for staging such an encounter with some large existential questions:

What is desire? The form of this cute Asian girl, why does it have such a grip on me? ‘Cause she’s the opposite of me? She gonna complete me in some way? … Why are some of us attracted to the opposite form and some of us the same? Sex is a poetic act. It’s a metaphor. Metaphor for what? Are we our forms? Am I a middle-aged white guy on the inside, too? Or inside could I be an Asian girl?

This line of reasoning follows from Luang Por Teera’s (Suthichai Yoon) words to Piper, heard over audiobook in “Same Spirits, New Forms”:

Identity is a prison. No one is spared this prison. Rich man, poor man, success or failure. We build the prison, lock ourselves inside, and throw away the key.

Frank, through his extreme sexual behavior, attempts to escape the prison of identity. However, he finds himself stuck to the notion of corresponding to a specific gendered, racialized form as his “inside,” the “authentic self” rather than totally annihilating the self. Frank’s act may fall short of transcendence to the extent that he instrumentalizes other people’s identity in service of his own pleasure. But something is missed here in conceiving of Frank as only treating others as objects in the course of this exploration. In the scene he describes, he pays the woman who observes and solicits men through the use of an advertisement. In contrast to the normal, imbalanced power relation where a wealthy white man exchanges money for sex in an oblique or explicit way, Frank’s queer sexual encounter requires a kind of assent (as distinct from consent, a different knot to untangle) beyond the simple exchange of sex for money. Likewise, the woman involved as a spectator is asked to do comparatively less in contrast to the “normal” scenario of old, wealthy white men dating young Thai women. At the level of demand, there is a redistribution of whose needs are satisfied through what means.

Mike White is also compassionate toward all parties subject to his gaze, including the white men and Thai women who ostensibly appear to be in a relation of exploiter and exploited. In “Killer Instincts,” Victoria asks the young girlfriend of Rupert (Rob Carlton) if she is with him for the money to which she indignantly responds, “I actually love Rupert.”

Such an arrangement, according to The White Lotus, may be more symbiotic than it appears.

Identity and the Pleasure Principle

The symbiosis of the relationship between Rupert and his girlfriend or the triangular relation among Frank and his solicited erotic partners hinges on demand. As opposed to desire, which is unconscious according to Lacan, demand is how wants (desires only in the colloquial sense) are articulated by a subject. But the satisfaction of a demand leaves desire behind as a remainder, hence the incessant repetition of Frank’s preferred sexual arrangement. Desire itself is a perpetual metonymy, as Luang Por Teera suggests in his conversation with Tim in “Denials”:

Everyone run from pain towards the pleasure. But when they get there, only to find more pain. You cannot outrun pain.

White’s avatar for Buddhism puts at the crux of his teaching the abolition of the identity, suggesting that identitarian attachment subjects one to the law of the Freudian pleasure principle:

In the theory of psycho-analysis we have no hesitation in assuming that the course taken by mental events is automatically regulated by the pleasure principle. We believe, that is to say, that the course of those events is invariably set in motion by an unpleasurable tension, and that it takes a direction such that its final outcome coincides with a lowering of that tension—that is, with an avoidance of unpleasure or a production of pleasure. (Beyond the Pleasure Principle Strachey trans.)

In White Lotus, White shows how the maintenance of an identity orients one to the goal of pleasure seeking. This may be in the form of “expectations,” as Tim confesses to Victoria in “Full-Moon Party,” or the sexual compulsions of Frank or Greg, or the ambitions of Gaitok (Tayme Thapthimthong), or the relentless hunger for approval of Lochlan Ratliff (Sam Nivola), or the need for a specific external presentation that Jaclyn, Kate Bohr (Leslie Bibb), and Laurie all share. The list could go on and on. All the characters’ aspirations are to exist in the world in a certain way that will bring them pleasure rather than pain, but the certainty of that way requires a degree of harmony between how one perceives themselves and how one is perceived by others. In a word, identity. At the same time, as the characters interact, the coherence of that identity is constantly threatened. To that extent, the hiding and seeking of Tim and Greg’s conversation become synonymous.

One hides from that which might threaten their identity and aspires to what can solidify it. In the end, however, this simultaneous evasion and aspiration induces an encounter with the very threat to identity, that which is beyond the pleasure principle: jouissance. The question of this season of White Lotus, then, is whether such an indifference to pleasure, pain, and identity is possible for the ideologically entrenched subject of late capitalism. Or are the expectations, the “shit put on” the subject “from day one,” impossible to evade? These expectations may themselves be the all too overbearing inscription of the signifier that subjectivizes an entity in the course of the mirror stage and turns the nothing into something. Luang Por Teera posits a final alternative to this compulsory ejection into the symbolic order, death: “no more separated, no more suffering.”

Weekly Reading List

From Shining Life Press, FLOORPUNCH: No Exceptions 1995-2000 is out today. You can purchase it here.

https://www.highsnobiety.com/p/best-workout-clothes/ — Sami Reiss gives some product recommendations I can get behind as both author and photographic subject.

Until next time.