Issue #374: The White Lotus Finale, Lazarus Premiere, and Australian Survivor

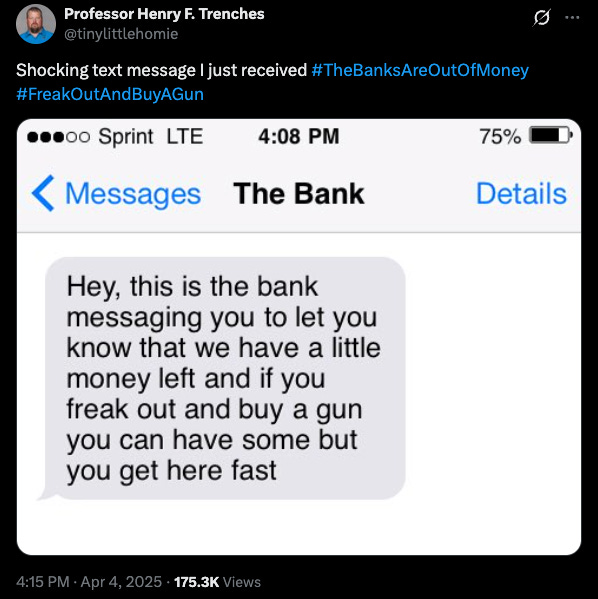

Economic collapses tend to make for good memes. One that has been circulating across the decaying corpse of twitter is simple: #TheBanksAreOutOfMoney.

There are a couple things going on here. First, this scenario is something with a tangential relation to general economic strife.

Banks may be harmed in the making of this depression, as we saw in 2008. So there’s a small degree of logic that governs the emergence of this — to be clear — untrue situation.

There is also the thematic association between economic collapse and banks being at risk of… running out of money.

But I read this meme as a little more aspirational.

Most people don’t love financial institutions unless they work for one, and perhaps not even then. A mass divestiture of capital from banks, a panicked withdrawal following the logic of panic-buying gasoline or toilet paper, could actually present an existential threat to banks that would not put people’s money at risk. After all, they withdrew it.

The idea of people frantically pulling their money out of the bank also entails a more obvious disruption to the normal functioning of life than we have seen thus far in this latest Trump administration. It is, perhaps, a disruption that is proportionate to just how much normal life has changed. After all, international students are getting their visas revoked because of parking tickets and being signatories on op eds.

The banks may not be out of money, but the United States’ population’s collective response to the many other extreme changes seems insufficient compared to those changes’ severity.

Some quick hits:

Long-tenured Japanese market in Medford Square, Ebisuya, is closing. If you live in the area, get there while you can.

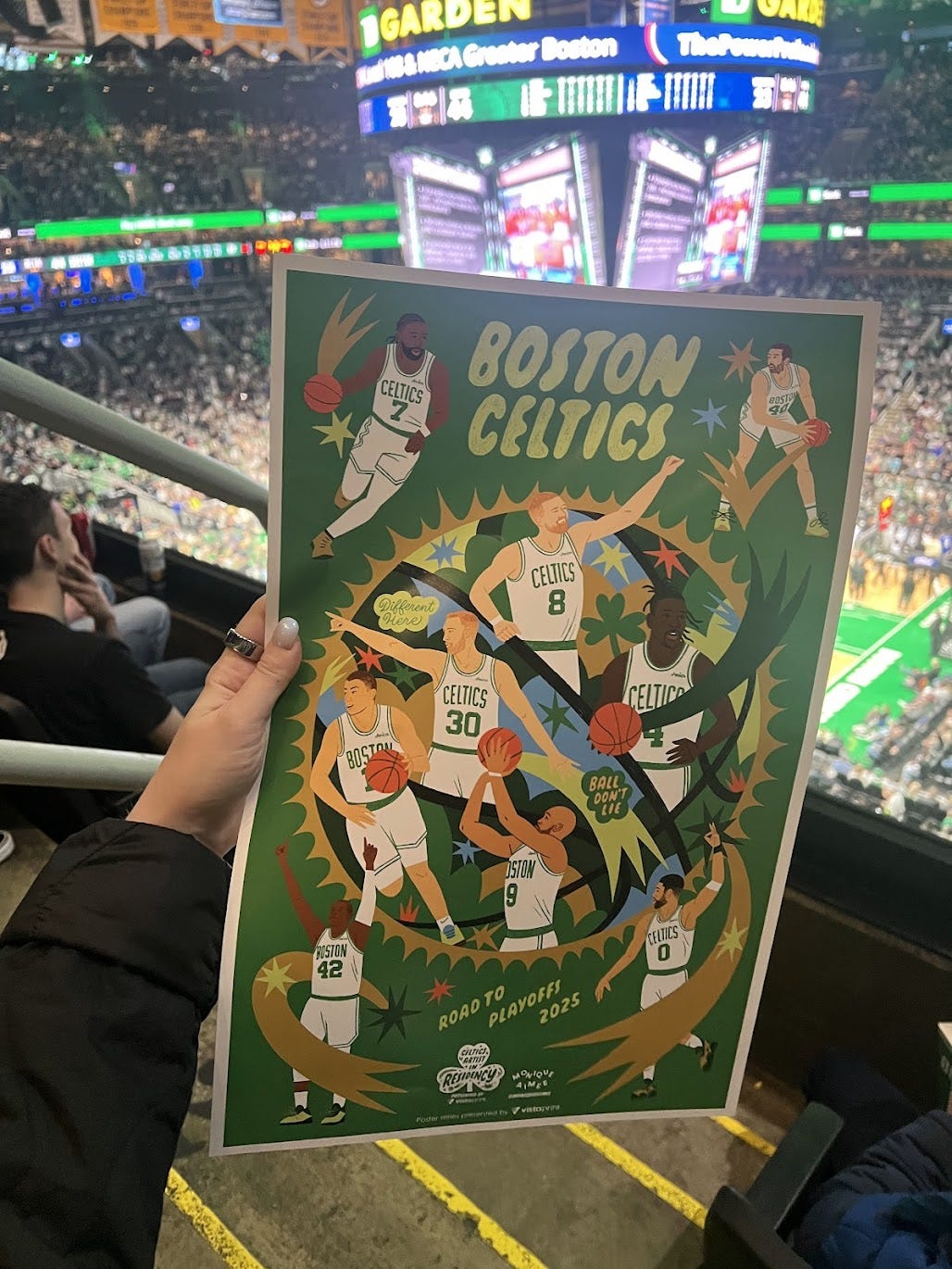

Friend of the letter Monique Aimee made some posters for the Boston Celtics. Her last one was distributed at a game last night. They are sick. Congrats Monique!

Strawberry biscuits are back at Popeye’s. Walk, don’t run.

Mobile Suit Gundam GQuuuuuuX (2025) premieres on Amazon Prime Video tomorrow (4/8)

As far as sections, a lot of topics are represented this week, including The White Lotus’s finale. I put the WL section at the bottom, so if you’re not caught up, don’t scroll all the way down.

RIP Al Barile

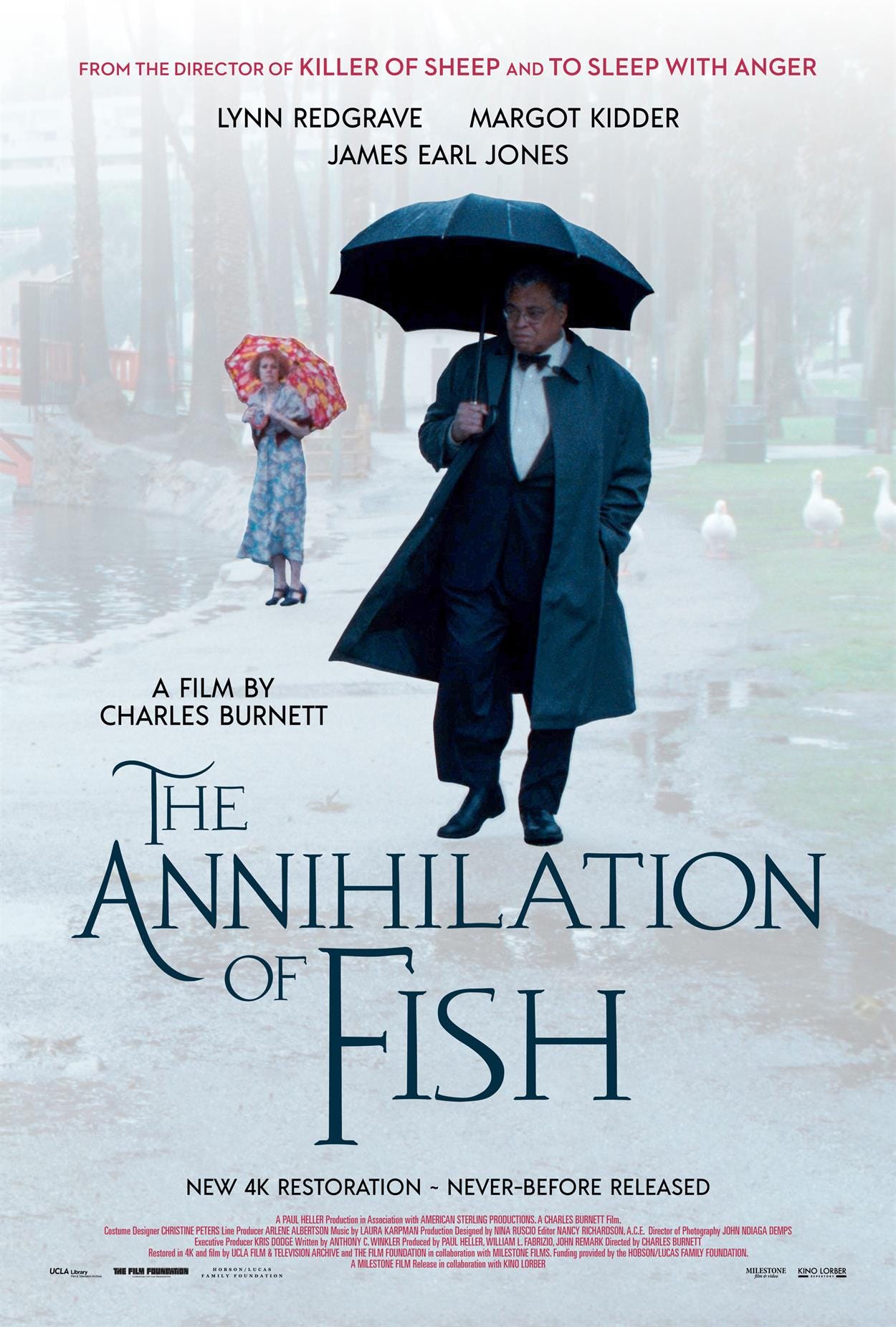

The Annihilation of Fish’s Undeniable Return

Charles Burnett’s beautiful The Annihilation of Fish (1999) has a new remaster from Milestone Films. I saw it at the Brattle two weekends ago and the film’s assistant editor was in the audience behind us with her entire family. I must admit, shamefully, I hadn’t yet seen Burnett’s work until this film. I have owned copies of Killer of Sheep (1978) and To Sleep with Anger (1990) since about 2016. I keep meaning to get around to watching them. But I would be shocked if they have the same vivid, stylized aesthetic of The Annihilation of Fish. It has similarities to Tim Burton or Wes Anderson, but there is something more naturalistic about the performances (by comparison) despite the very peculiar premise of the film.

In it, the titular Obadiah ‘Fish’ Johnson (James Earl Jones) wrestles an invisible demon and Flower ‘Pointsettia’ Cummings (Lynn Redgrave) attempts to marry the presently deceased composer Giacomo Puccini. The two end up living in the same boarding house and spark a romance. The film is adapted from a short story by Jamaican writer Anthony C. Winkler.

The film, and its new restoration, comes with my highest recommendation.

Pain’s Instruction in Lazarus’s “Goodbye Cruel World”

Shinichirō Watanabe, because of Cowboy Bebop (1998), is inextricably tied to the popularization of Japanese animation in the United States. It’s true, Cowboy Bebop is neither Dragon Ball Z (1989) nor Naruto (2002). But Cowboy Bebop served an even more critical function in the assimilation of anime into American culture: asserting artistic legitimacy. As Watchmen (1986) is to comics, Cowboy Bebop is to anime.

As one of few truly “adult” anime, it wasn’t adapted from a manga, let alone one for elementary school students. It couldn’t air in its entirety on Japanese broadcast television — TV Tokyo ran only five specific episodes of the series in a 6pm time slot. In 2001, it appeared on U.S. televisions as part of the Adult Swim programming block with a groundbreaking English language dub including Steve Blum, Wendee Lee, and Beau Billingslea. This trio proved yet another critical point; anime voice acting is an art unto itself. Yes, it’s true, Claire Danes, Billy Crudup, and Billy Bob Thornton turned in outstanding performances in the 1999 Disney dub of Princess Mononoke (1997), but every Ghibli dub that uses A-list Hollywood talent always falls a little short of the transcendent English voice work of the Bebop cast.

All of this brings us to Lazarus (2025). Twenty-four years after Cowboy Bebop’s English language debut, another totally original Shinichirō Watanabe sci-fi anime has premiered on American television, this time on the semi-recently Adult Swim-ified Toonami. It comes to U.S. and Japanese airwaves simultaneously. This time, it seems, TV Tokyo is satisfied to air the series in its entirety.

Lazarus, so far, is remarkable. Dr. Skinner (David Matranga), the inventor of a miracle pain relief drug called “Hapna,” disappears from public life before announcing that all those who have consumed the drug will die after three years of having ingested it. The episode’s opening narration describes Hapna as “free[ing] people from all suffering.” Dr. Skinner also emphasizes the efficacy of the drug in his worldwide ransoming of the entirety of human existence:

If you find yourself unable to feel any kind of pain, then that is no different from being dead. While it is unfortunate, due to its dependency on Hapna, mankind as we know it is dead.

Dr. Skinner has delivered, it seems, “a cure for mankind,” but condemns humanity for their willingness to cure themselves from themselves. Funnily enough, there is some strong thematic overlap with Severance (2022) here. Hapna is the same kind of sci-fi MacGuffin as the severance procedure. They also share the promise of curing pain with the necessary side effect of eliminating that which is human in the subject — inextricable from pain. The name “Hapna” carries the association with “haptic,” negating all haptic sense as opposed to only pain.

In his confession, Dr. Skinner insists he is not playing god but identifies himself as the “Seventh Trumpeter.”

In this allusion to Revelation 11:15-19, the seventh trumpet announces the “third woe,” a conclusion to the plagues that accompanied the preceding trumpets. From Revelation:

The kingdom of the world has become the kingdom of our Lord and of his Messiah and he will reign for ever and ever

One reading is that this is a relief for humanity from the onslaught of plagues. This means the perpetuation of human existence under God’s watchful benevolence. Another is that this trumpeting marks the cessation of the world of mortals in favor of God’s kingdom, one in which no humans are involved.

Axel Gilberto (Jack Stansbury), the show’s incarcerated protagonist, contrasts the pain-avoidant version of humanity that Dr. Skinner condemns. He gives no indication of being ecologically conscious — Skinner justifies Hapna’s destructive turn claiming that humans have “irreparably destroyed the environment of our planet.” He also seems to, perhaps, be subject to the short-term thinking Skinner describes, but, crucially, Skinner faults humanity for their “fixat[ion] on short-term gains.” Gilberto seems content to lose in the short term, compulsively escaping from prisons even when paths of lesser resistance present themselves.

Skinner’s ultimatum sets into motion Lazarus’s plot by setting out a possibility of avoiding the fate to which Hapna has consigned humanity: find him in thirty days to, presumably, disseminate the cure he claims to have. Gilberto is recruited to a group called Lazarus along with Douglas Hadine (Jovan Jackson), Christine (Luci Christian), Leland (Bryson Baugus), and Eleina (Annie Wild). Hadine seems wistful in his consideration of theological ideas. Early in the episode, he asks to listen to music “with the vibe of a man who sold his soul to the devil,” alluding to Robert Johnson but also suggesting that perhaps Skinner or Gilberto have agreed to such a bargain.

If Dr. Skinner’s concern is even in part humanity’s potential for acting in favor of long-term interests, his announcement that everyone who has taken his drug will die as a result has the opposite effect in “Goodbye Cruel World.” Leland is enthusiastic about being relieved from the obligations of normal life.

Gilberto uses the chaos of riots and panic to prolong his escape.

But it seems to me there is something more at issue than the ability of humanity to act in the interest of the world as a whole. Pain may be the stick, the necessary haptic response, that confines human behavior within a set of parameters. For those with congenital insensitivity to pain with anhidrosis (CIPA), the necessity of pain becomes obvious. CIPA patients have an extremely high mortality rate.

Regardless of pain’s evolutionary function to help an organism behave in such a way that they live longer, there is an existential component of pain that, specifically for humans, is a necessary condition for life itself. Following the CIPA allegory, someone with CIPA may not feel haptic pain, but they encounter plenty of emotional pain as a result of their illness.

It’s the inability to fully disentangle painful feelings from feelings of other kinds that — certainly in Severance, and perhaps in Lazarus — creates such a grave risk when taking extreme measures to avoid pain. From Dr. Skinner’s perspective, what Hapna took from humanity was life itself. Gilberto’s quest to find him is the quest to get life back.

Australian Survivor Interlude

Are there any Paradox readers watching Australian Survivor (2002)? I started watching with the previous season, eleven, which was an all timer. Now, the currently running season twelve probably won’t eclipse it. But it is unbelievable. Australian Survivor runs for 47 days of competition distilled into about 24 episodes. It also airs three days a week. It would be hard to keep up with even if I did not need to go through a circuitous process to view it.

Australian Survivor has the intangibles that make it a better show than its U.S. counterpart. It has a more interesting cast than the last ten or so seasons of Survivor (2000) and a stronger sense of what deserves to be in the edit and what doesn’t. But show’s edit is also unforgiving. It has huge disparities in screen time between those favored to win and those who will certainly meet an earlier end. The Australian producers seem unconcerned with the Survivor “edgic” to which the American producers have been responding, aggressively, to the show’s detriment.

The show embraces camp — as in style, not the place the contestants spend their time — in its visual language far more than its U.S. counterpart. In the episode “G-R-I-M,” the merged contestants are re-split into new “Bounty” and “Barren” tribes. On the Barren beach, the picture is desaturated and bleak. Following the Bounty tribe, the brightness and saturation is punched up. I’ve never seen anything like it on Survivor.

And then there’s Paulie.

He has taken some of the worst heat from the edit, with host Jonathan LaPaglia describing Paulie as “on the crucifix” during the eighth episode’s immunity challenge. Speaking of Jonathan LaPaglia, JLP as the contestants call him, he’s a spectacular host. He borrows all of the requisite Jeff-isms, the kinds of repeated statements that make Survivor Survivor, but unquestionably has the charism to make them all his own.

This latest season also has unprecedented gameplay, involving “hostages” and exhortations for the opposing tribe to throw challenges lest their allies get voted out. I don’t want to spoil much. I bet most people reading this haven’t seen it, and I think you should watch it. We’re twenty two episodes deep, almost done. If you try to catch up now, and you’re a Survivor fan to begin with, I doubt you’ll be able to look away unless you’re forced.

“There is no resolution”: Non-Identity and Negativity in The White Lotus’s “Amor Fati”

The White Lotus’s (2021) finale, “Amor Fati,” opens with what amounts to a summary of what is to come. The words are spoken by Luang Por Teera (Suthichai Yoon), the last he will speak in the episode:

Sometimes we wake with anxiety. An edgy energy. What will happen today? What is in store for me? So many questions. We want resolution, solid earth under our feet. So, we take life into our own hands. We take action, yeah? Our solutions are temporary. They are quick fix. They create more anxiety, more suffering. There is no resolution to life’s questions. It is easier to be patient once we finally accept there is no resolution.

No resolution. Temporary solutions. This is a narrative confession. Belinda (Natasha Rothwell) might get her money, but she loses her compassion in exchange. Rick (Walton Goggins) and Chelsea (Aimee Lou Wood) are floating bodies, returning to the evocation of the swamp-like war zone through which Zion (Nicholas Duvernay) wades. Gaitok (Tayme Thapthimthong), too, sacrifices his theological morality in exchange for the practicality Mook (Lalisa Manobal) insists upon.

Laurie (Carrie Coon) breaks, for a moment, the self-congratulatory stupor of her deceptive friendship with Kate (Leslie Bibb) and Jaclyn (Michelle Monaghan), but risks being repetitively thrown into the same antagonistic dynamic rooted in self-doubt in the face of the other. And the season closes with Timothy (Jason Isaacs) wistfully watching water droplets fall, regretting his decision to live subject to his family’s resentment and his impending impoverished imprisonment.

Laurie and her friends seem the closest to getting out clean as they rejoin one another as the “blonde blob” Mike White instructed Bibb, Coon, and Monaghan to embody. What White ultimately seems to dispute in this season of The White Lotus is any a priori system of categorization for human beings. We are separate, perhaps, only by accident. Chelsea insists to Saxon (Patrick Schwarzenegger):

we’re all connected … these groups are working together to fulfill this divine plan. And sometimes you don’t even know you’re in the same group as someone else.

Aside from Chelsea, the transcendent spiritual voice of the show — collateral of the tragic plot structure — characters are ruled by self-interest. They are attached to the things that cohere their identity. Piper (Sarah Catherine Hook) confesses to her parents her investment in her privilege and her guilt.

She can’t survive without air conditioning or organic food. She says, “I know I’m not supposed to be attached to this kind of stuff … but … I know I am.” Victoria (Parker Posey) consoles her in one of the episode’s strongest moments:

We’re lucky. It’s true. No one in the history of the world has lived better than we have. Even the old kings and queens. The least we can do is enjoy it. If we don’t, it’s offensive. It’s an offense to all the billions of people who can only dream that one day they could live like we do.

The truly destitute dreamers probably have minimal investment in whether the haves enjoy their vacation or not. But Victoria is right, even in the logic of the show, to a point. The guilt Piper feels is as useless a feeling as anything. Without the reciprocal divestiture of privilege redistributed to others, the guilt is more offensive than the ostentatious displays of wealth. And while I’m not sure the show endorses this view, I agree with Victoria to the extent that if the choices are between overpowering, self-soothing, guilt or pleasure, one should choose the latter.

In The White Lotus, wealth only moves at proverbial or literal gunpoint. Valentin (Arnas Fedaravicius) steals from the resort to supplement his income. Jim Hollinger (Scott Glenn) exploits Thailand, consolidating wealth rather than distributing it.

And Belinda gets her five million from Greg (Jon Gries) by threatening him.

Wealth is also crucial for each character’s self-image. I want to read closely Saxon’s taunt of Lochlan (Sam Nivola), “no one’s gonna make you a man. Okay? You gotta do it yourself.”

If we take Saxon’s words in the spirit they are intended, he suggests identity emerges from one’s actions. This seems, at best, misguided — Saxon clinging onto the view Chelsea seems to be dissolving through her spiritual guidance. Tim’s manliness, for instance, that which Saxon aspires to, is his birthright only by accident. And it has nothing to do with his biological status, but rather his social positioning by virtue of the expectations he chafes against in “Full-Moon Party.” He returns to the spirit of this idea again in his cultish farewell to his soon-to-be-poisoned family:

I couldn’t ask for a more perfect family. We’ve had a perfect life, haven’t we? No privations, no suffering, no trauma. And my job is to keep all that from you, to keep you safe. ‘Cause I love you.

He evokes both Jim Jones and even Sethe from Morrison’s Beloved (1987) attempting to reposition his filicide as an act of love. One can, and should, recognize the profound difference between the context of chattel slavery that Sethe’s unnamed daughter is subject to and the loss of financial security the Ratliff’s will be subject to. At the same time, for Tim and Sethe, their momentary perception of the threat is the same. For their children to live under these conditions would be equivalent to utter annihilation — for all except Lochlan.

This belief also relates to the urgency of Tim’s impetus to protect his family. This is coextensive with his masculinity, the idea of himself as a man. What is at issue here, then, are not his actions — although he strives to act in accordance with the stated and unstated expectations befitting his subject position — but the life he has been thrown into. Saxon is wrong to say “no one is going to make you a man.” For Tim, we see how everything conspired to turn him into one by hook or crook. The same is true for Saxon, Lochlan, Victoria, Piper, and everyone else in the show. The identity they embody is the result of powerful external pressures. Each makes a choice how to respond to those pressures. They will assent and embody the identity that society throws them into or revolt and reject that identity, act out, refuse, and be “left out,” excluded.

But the identity one inhabits is contingent and compelled, never truly “authentic,” corresponding to a subject’s essence.

Again, it seems to be Laurie who is closest to understanding the complex triangulation and compulsion that forces one into manliness, womanliness, parenthood, or pacifism. She says she has “no belief system,” but then goes on to outline not beliefs, but subject positions she attempts to inhabit to give her life meaning: accomplished attorney, dutiful wife, self-sacrificing mother.

These are roles that are in conflict with each other in various ways. The traditional feminine subject position is set against the modern career woman. The antagonisms and jealousies of family drama as one navigates their position of romantic lover and matriarch, a problem of Oedipal proportions that unfolds more acutely for Rick as well as, separately, the Ratliffs. These guiding ideas are correlative to religious belief to the extent that they serve to cohere an identity. But Laurie seems to realize they all fall short of giving her the wholeness she thinks she sees in her friends. Even that, she recognizes, is illusory, complementing her friends defining characteristics as “a beautiful face” and “beautiful life.”

While physical beauty or a conventional domestic framework may be foundations for a version of one’s subjectivity, they are ultimately markers that cover over the lack we all share, that absence that is, in fact, a tie that binds unknowingly.

If Laurie escapes tragedy, and Tim’s tragedy is that he won’t go far enough, Rick’s tragic flaw is ignorance. Though he is the surprise Oedipal figure of the series, with his patricide as a structural analogy, Rick does not seek the truth but to recover an impossible lost object. He attempts to balance the ledger that is inscribed with an incalculable, inscrutable loss. His “solution,” as Luang Por Teera warns in the episode’s opening, “create[s] more anxiety, more suffering.”

No one acts in accordance with the episode’s title, “Amor Fati.” Chelsea says, “It means you have to embrace your fate, good or bad. Whatever will be will be.” Literally, though, it means to love your fate. And Mike White, too, calls upon his viewers to love their fate in a show that won’t resolve itself by showing Belinda’s wealthy life, Tim’s arraignment, or Laurie overcoming her perpetual dissatisfaction.

The episode ends with the Billy Preston song, “Nothing From Nothing,” where the speaker cautions the listener against the absolute negativity of “nothin’.” He demands, from an ostensible lover, “somethin’” in opposition to that absence. But this demand will always fall on deaf ears. Nothing is all that exists beneath the facade of identity that one aspires to. This negativity is the non-answer to the questions of life with which each character grapples. It is also that which undoes the identities to which they cling.

Weekly Reading List

https://archive.org/details/essays-and-aphorisms-schopenhauer-arthur-1788-1860/mode/2up — Sometimes you just need to revisit a classic.

Don’t know how long this will be available, but I just found Australian Survivor on youtube right before sending the letter out.

“Big Night” amphibian migration is ongoing across the northeastern United States (and wherever else temperatures are finally hitting above freezing during rainy nights).

Until next time.