Issue #379: The Rehearsal Skips Low-Hanging Fruit of The Little Mermaid References

This past week, I took a break from the movietheater and breezed through a bunch of movies that were mostly just okay. One of Them Days (2025) was funny enough as a nice flick to run immediately after work. The Woman in the Yard (2025) was terrible, skip this one. Freaky Tales (2025), an Oakland-set anthology film named after a Too Short song, delivered absolutely nothing I expected. The first bit, involving Negative Approach and Black Flag songs, was painful to watch. It only got better from there, though. There’s probably a full 120 minutes worth of movie you could get out of Pedro Pascal’s character, Clint. And Jay Ellis as the actual Warriors player Sleepy Floyd was sick.

Companion (2025) felt like a miss overall, but it was hard to watch in a way that indicates strong work on the part of Drew Hancock. He seems to have a profound grasp of the male gaze and what makes it so horrifying.

This week, my exploration of The Rehearsal (2022) continues. It remains so good and so hilarious.

“Let the games begin”: Rules of Behavior in The Rehearsal’s “Kissme”

The Rehearsal (2022) is taking its audience through a cycle in its exploration of how affect functions. The thesis of the second episode of season two, “Star Potential,” is “everything is a performance.” Feeling, genuine feeling, is disconnected from how one behaves or appears to others. One’s only recourse is to convey feelings through performance, both conscious and unconscious. This logic has underwritten the entirety of the season’s first three episodes.

Now, in episode four, “Kissme,” we are entering different territory. Fielder says:

It was like the concept of acting itself disarmed everyone in its presence. And the actor gets a free pass for virtually any behavior. Everything I’d been trying to do just comes down to getting co-pilots and captains to both act on their true feelings. Either speaking up about their fears, or admitting to your co-pilot that you might not know everything. These are feelings that every pilot already has, but may struggle to act upon because they fear the consequences. Could the concept of acting give pilots a loophole to do the things they’re most afraid of?

Once again, the humor of the show comes from Fielder appearing to learn an obviously wrong lesson from the circumstance he is observing. Nearly everything leading up to this realization delivered through internal monologue indicates that acting is precisely separate from the actor’s “true feelings.” The person acting delivers their performance not because their feelings are real, but because they are serving some narrative. The one actor aside whose comments Fielder latches on to (she says, “the emotions feel real” but also describes the brute reality of the actions of acting), even Fielder’s own experience he describes in the course of filming The Curse (2023) indicates that performances are not manifestations of the actor’s true feelings.

The idea that Fielder embraces is that acting is a “loophole” for action to occur without consequences and that such a loophole would allow people to take an action they really want to, but otherwise wouldn’t. “Kissme,” however, does complicate this belief. Fielder introduces an intimacy coordinator for the five instances of predictive rehearsals for Colin and Emma’s relationship. The intimacy coordinator prompts Fielder to make decisions about “what is the story that you want to tell through the intimacy.” Fielder refuses to answer, saying “I’d like to leave it up to [the actors].” It is immediately obvious that the scenario in which Fielder is putting these actors is not “a traditional acting role,” thus the specificity of the circumstance is what helps lead Fielder to his conclusion. What he believes about acting is not necessarily true about “traditional acting,” but it is true in the bizarre scenario he created for the actors.

Fielder repeatedly tries to deny his agency, not acknowledging the imperatives created by his unusual TV series or the implicit imperatives of the camera itself. The entirety of Nathan for You (2013) and The Rehearsal show the way one might perform for the camera even when supposedly not acting. Reality TV scholars like Chad Kultgen and Lizzy Pace observe that any “abnormal compulsions or activities … like humorous sleep-talking or a bizarre workout routine would work perfectly for you to garner screen time” (How to Win the Bachelor 23). Their “advice” in their semi-satirical Bachelor (2002) treatise reflects the fact that people exaggerate these quirks under the camera’s watchful eye.

Both acting direction and the camera itself impose a framework for behavior that everyone responds to in The Rehearsal. Even without the camera, society itself is not without such a framework — evident in Fielder’s insistence that “sincerity is overrated,” as he says in “Star Power.” Considering these structures, Lacan’s discussion of courtly love in Seminar VII: The Ethics of Psychoanalysis (1986) is a productive intertext. Lacan writes:

courtly love was, in brief, a poetic exercise, a way of playing with a number of conventional, idealizing themes, which couldn’t have any real concrete equivalent. Nevertheless, these ideals, first among which is that of the Lady, are to be found in subsequent periods, down to our own. The influence of these ideals is a highly concrete one in the organization of contemporary man’s sentimental attachments, and continues its forward march (148).

The most explicit echo of courtly love is in the idea of “codes,” “tricks,” or “signals” Emma and an actress playing her (Evi Eden) in one of the rehearsals describes to Fielder.

What Fielder seems to be willfully ignorant to, for the sake of both the show’s humor and social commentary, is that these implicit signals are more determinative of one’s actions. Such signals can also come from one’s position relative to a camera.

At the same time, without the elaborate structure of courtly love that Lacan traces through ethics, realpolitik gender relations, libidinal economy, and the art of Ovid and Breton, these signals may be lost in translation. What one attempts to communicate, without explicit instruction, may not be received by the other. This signaling ambiguity is where acting comes in for Fielder. But he is wrong, as the episode is structured to show, that acting unleashes one’s desire or accommodates one’s demand. One acts in accordance of another set of implicit imperatives when acting without directorial guidance.

As I close read this episode, I have greater sympathy for Alan Sepinwall’s taxonomy of Nathan Fielder I critiqued three weeks ago. In “Kissme,” Fielder-on-screen and Fielder-behind-the-camera are explicitly at odds with one another. Though he suggests in his spoken lines that “the concept of acting [could] give pilots a loophole to do the things they’re most afraid of,” the episode is structured to show how acting exerts a demand on its object as opposed to allowing the object to behave freely.

In Ethan Shanfeld’s coverage of Rehearsal contestant Lana Love for Variety, we have ironically a fitting companion to the episode in the form of what is an ostensible take down of Fielder and the show. Love describes her expenditure of money — $5,500, she alleges — and lost wages — $4,000, she estimates — all for the sake of getting on camera. She describes feeling deceived by the fact that Wings of Voice was not actually a show that would air its own episodes, but rather a bit inside The Rehearsal. Even as she tries to “expose” this confusing circumstance, her co-stars implored her not to. Shanfeld writes, “[m]any of the contestants, now knowing the show was fake, still viewed it as an opportunity to sing in front of a camera.”

This is the powerful compulsion of the camera. One discusses sexual fantasies of Einstein, spends thousands of dollars for a narrow chance for career advancement, or agrees to play opposite a character named “Jennifer Kissme.” Love’s supposedly indignant NDA-violating disclosure to Variety comes with its own caveat. The publication was gracious enough to promote her upcoming single from Warner Music Group.

Hater Report Report

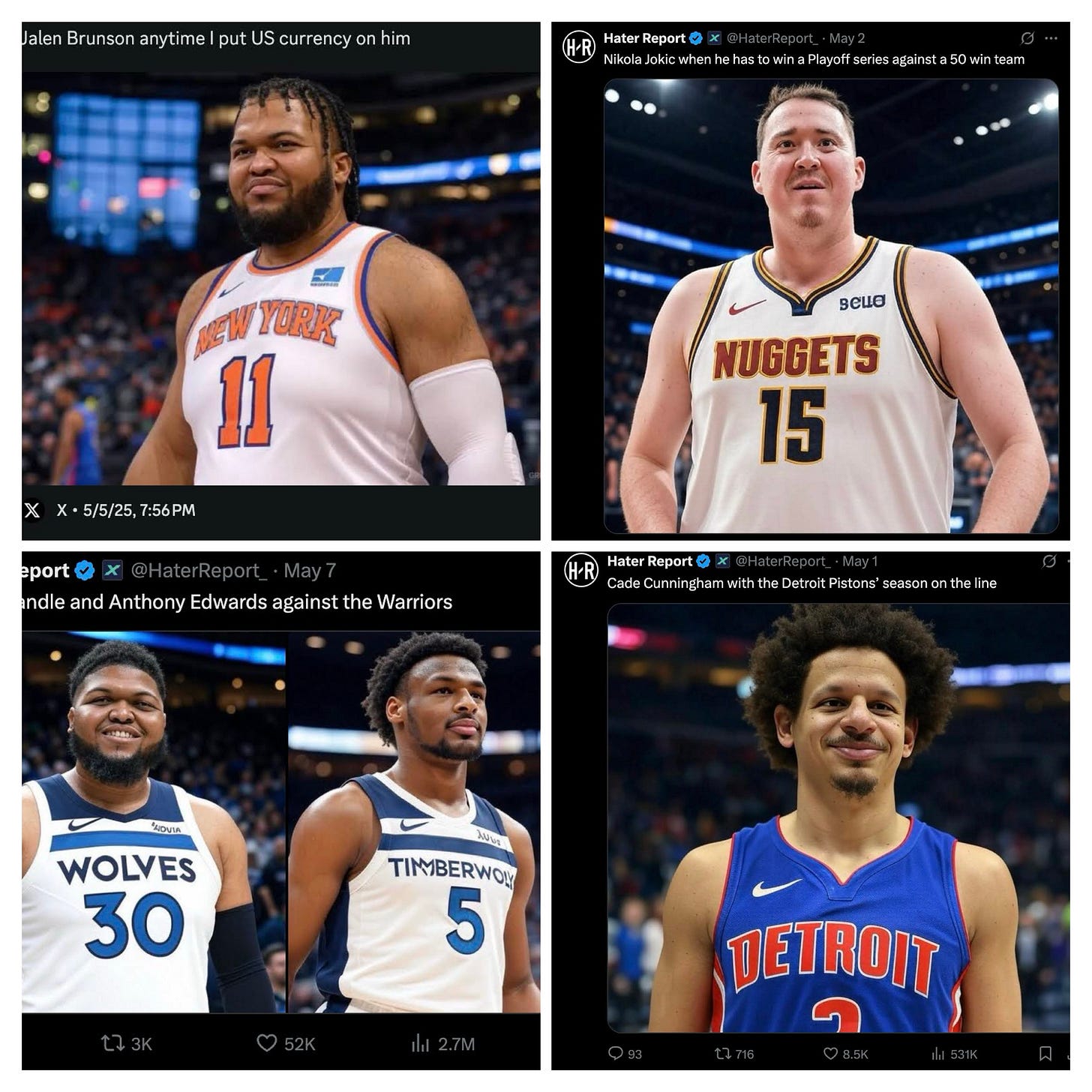

Hater Report is a satirical NBA news twitter account that is modeled in the tradition of NBA Centel and Ballsack Sports. NBA Centel is an intentional misspelling of NBA Central, often confused with the non-satirical news account. Ballsack Sports also attempts to represent itself as a legitimate news organization, resulting in other platforms that repost their Onion-esque headlines being “sacked.” Hater Report is a little different, though. It would be tough to confuse their coverage for legitimate headlines. And they are really, really focused on negative commentary, critical of poor play from any player or team on any given night. They live up to their name.

They often photoshop the faces of players onto others or, alternatively, the faces of comedians or other people onto the bodies of the players. They might also just find a picture of a lookalike to represent the player’s abysmal performance. Whatever might convey that the player is not playing up to their standard.

The captions with these photos are often pretty similar. “So-and-so with the season on the line,” “so-and-so when their team was counting on them,” “so-and-so when I put U.S. currency on them.” There’s an added dimension to the humor when it involves the critic losing their own money, and they don’t keep their diction simple either. It’s not “so-and-so when I bet on them,” there’s that accentuating flourish expressing the idea in an idiosyncratic way.

Even as the jokes repeat, I still find them pretty funny. Hater Report benefits from being edgy, too. Some of their choices for photoshops are pretty shocking. But that makes it a little funny, right? Sometimes, yes.

Weekly Reading List

Evo Japan 2025 is a wrap. Here are some highlights from the final day.

Until next time.