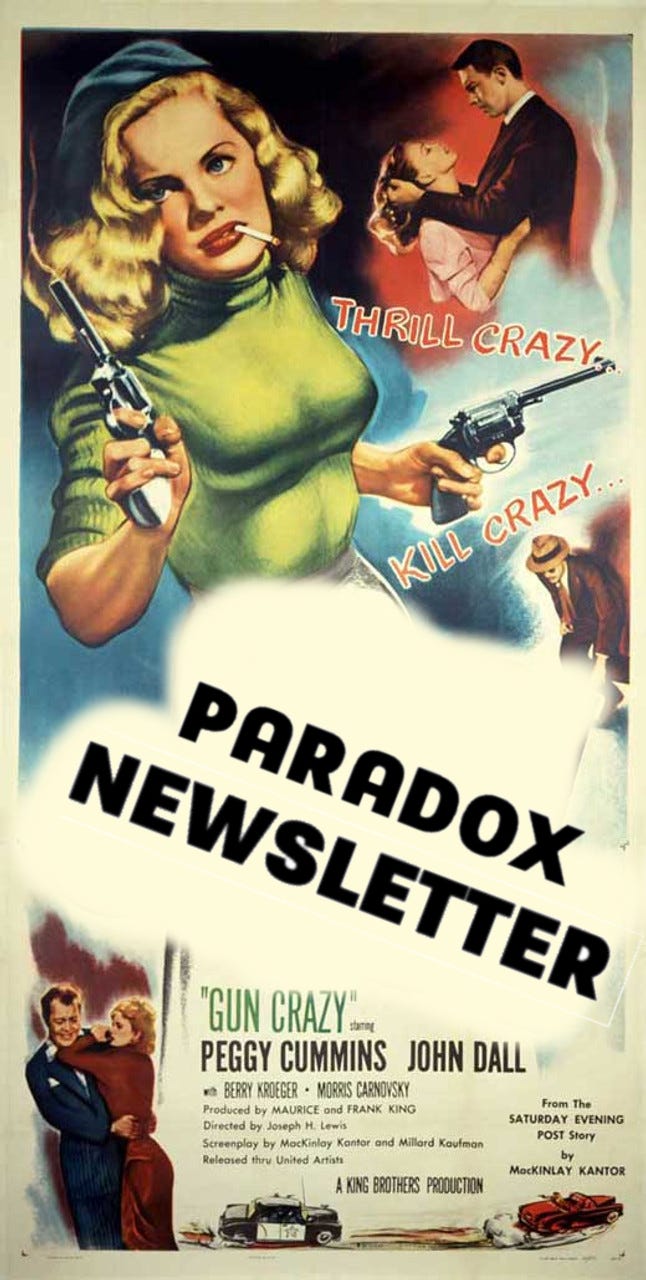

Issue #380: Where Does Gun Crazy Fall on My Top 100 Movies of All Time List?

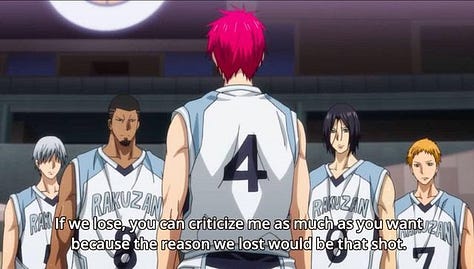

The Boston Celtics season is over. Despite my lifetime tenure as a Celtics fan, my enjoyment and understanding of sports is mediated by shounen sports manga and anime — which I have been a fan of for considerably less time.

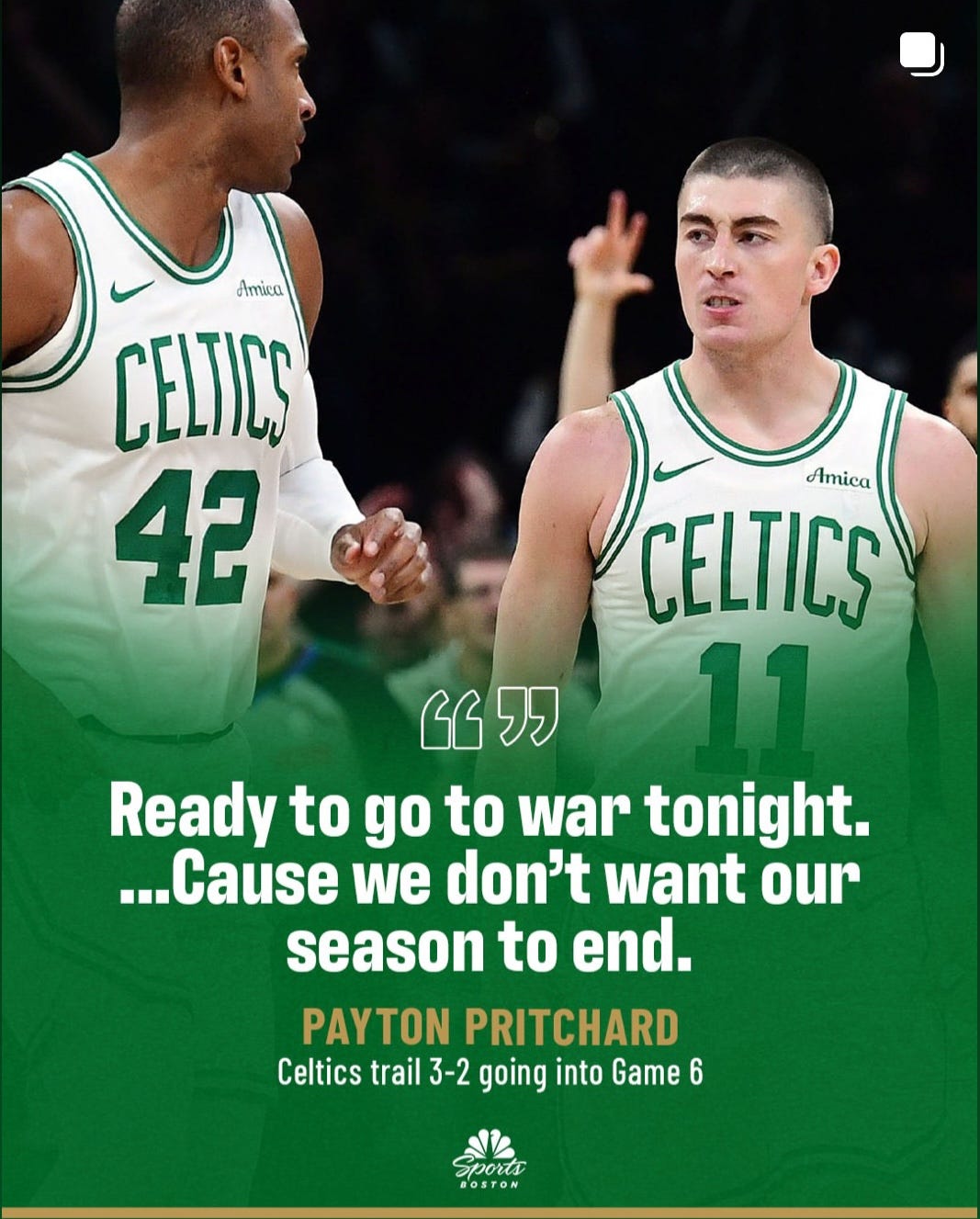

There is nothing nearly as dramatic this NBA season, but Payton Pritchard showed shades of a manga protagonist in his pregame press leading up to Game 6 against the New York Knicks.

The idea of keeping the season, summer, or tournament going, is a common motif in the genre. It analogizes the movement from adolescence to maturity, most of the series taking high school sports as their subject. The characters would often rather delay their transition into the world of adulthood in favor of maintaining the hierarchy of importance sports can occupy as a high school player.

Regrettably, Payton Pritchard did not play like a manga character.

His stat line doesn’t look atrocious, but his +/- was -17.

All this along with a Jayson Tatum injury make it a pretty dark time to be a Celtics fan.

Injuries are a reality of sports. And of 30 NBA teams, only one can be champion every year.

As the NBA season dials down, it opens up my viewing schedule for movies. This week, I saw the new 4K restoration of Killer of Sheep (1978). An absolutely stunning work, different from The Annihilation of Fish (1999) but with some unmistakable echoes from one film into the next. Great job to Milestone Films for keeping these in circulation.

I’m also very excited for the screenings of Gun Crazy (1950) at the Brattle Theater on Monday, May 26th. It’s showing on 35mm at 12pm and again at 4pm. I will be there. If you are on the fence about attending, I wrote about the movie this week. I tried to keep it relatively spoiler free, so unless you are 100% going to watch the movie and want to go in 100% blind, I think you’re good to read it.

Oh, and I indulged myself by joining in the ceremony of Tufts’ doctoral hooding despite getting my degree in August 2024. And I did some on the ground snack reporting. I’ll let my substack notes speak for me on those topics.

“Afraid I’ll shoot too low?”: The Psychological Radicality of Joseph H. Lewis’s Gun Crazy

A Prescient Psychodrama

Watching Gun Crazy (1950), I can’t help but wonder how provocative or shocking it must have been to see Bart Tare (in this scene, played by Mickey Little) shoot and kill a baby chick with his new BB gun.

Today, cruelty to animals is a well-known diagnostic criteria for Conduct Disorder in children and adolescents and a predictor of Antisocial Personality Disorder. In 1963, J.M. Macdonald established in “The Threat to Kill” what would come to be known as the “Macdonald triad,” animal cruelty, fire-setting, and persistent bedwetting that are popular in serial killer fiction as part of a killer’s childhood background. This is reflective of the usage of the Macdonald triad as an investigative and profiling tool by the FBI’s mythologized Behavioral Science Unit, first established in 1972.

But Gun Crazy releases thirteen years before Macdonald’s pioneering article and thirty years before these behaviors would become diagnostic criteria in the DSM-3, where they remain as of the current edition of the DSM-5. And Tare (John Dall), as it turns out, is not a serial killer or sociopath. In the early flashback, he immediately feels remorse. The scene establishes that his fascination with guns is coincident with a strong aversion to killing and a profound sense of empathy for potential victims. Toward the film’s conclusion, he says:

Two people dead. Just so we can live without working … You go into a racket like this to get something at the point of a gun, you have to be ready to kill even before you start a job. I’m as guilty as you.

Despite not having pulled the trigger, he finds himself equally culpable for the murders committed by his wife, Annie Laurie Starr (Peggy Cummins).

All of this is to say Joseph H. Lewis’s film is undeniably prescient, perhaps drawing from the early work on the topic of childhood psychology from William Healy and Hervey Cleckley. But it is also clear that the film is out of step with a psychological paradigm that consigns children to reformatories. In Criminal Youth and Borstal System (1941), Healy writes:

[I]n the face of the scientific advances of the past few generations in so many other fields, we very apparently have made little progress in dealing successfully either with the young offender who evidences the possibility of rehabilitation or with the really dangerous young criminal from whom society needs thoroughgoing, prolonged protection. (3-4)

In the text, Healy critiques supposedly rehabilitative approaches to adolescent crime, writing “In 1930 a competent study of one of the supposedly best reformatories showed that about eighty per cent of its graduates commit further offenses” (3). This is Lewis’s orientation, too, in Gun Crazy, pointing his audience toward the failure of a “reform school” to successfully deal with symptoms Tare earnestly attempts to resist.

The film, then, can be said to stage a confrontation between a compulsion and a moral compass. Tare is in the thrall of, above all, guns as a fetish in the Lacanian sense — “a protection against anxiety” (Seminar IV 15), one that substitutes itself for the abyssal absence of the phallus. This is also a culturally compelled fascination as human, U.S., subjectivity orbits around the gravity of the Second Amendment.

But Tare has another essential trait, the one that leads him to the disavowal of the relationship between guns and killing that follows the traditional structure: ‘I know very well guns are instruments of killing, but all the same I value guns as instruments [despite repudiating killing].’ To the extent Lewis's film makes a commentary on penalties for children under the law, he demonstrates the system that attempts to "reform," in fact, makes no intervention whatsoever into the psychic tension that affects Tare.

The Mark of Director and Screenwriter

Joseph H. Lewis talks about his salacious, sexually charged direction to John Dall and Peggy Cummins in Danny Peary’s Cult Movies (1981). But it’s clear, at least between Gun Crazy and Lewis’s celebrated The Big Combo (1955), Lewis sought out work that investigates the role and proximate cause of violence in society. In The Big Combo, nothing is ever simple. The villainous Mr. Brown (Richard Conte) is responsible for a murder, so says Leonard Diamond (Cornel Wilde), through a complex sequence of money transfers and circumstance. Diamond’s boss, Captain Peterson (Robert Middleton), insists Diamond abandon his pursuit of Brown, to which Brown replies, “he’s no more innocent than this gun!”

Just like in Gun Crazy, The Big Combo gives guns as an object an undeniable moral weight. They are not innocent, not simply tools to admire or objects to collect. Tare is mistaken in the embrace of guns as a fetish, but his embrace mirrors the modern fascination with guns. In the United States, guns are not embraced for their potential to kill but because of a more amorphous association with power and, indeed, phallic authority in both the colloquial and Lacanian sense. They are transformed into fetish object in cultural representations, like modern first-person shooters, where guns are decorated and customized.

Dalton Trumbo, the uncredited, blacklisted screenwriter of Gun Crazy, has as interesting a career as any Hollywood denizen. He was among the ten screenwriters cited for contempt on November 25th, 1947, for refusing to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), notable also for writing Roman Holiday (1953), Spartacus (1960), and Papillon (1973). One might easily infer the critique of U.S. gun and carceral culture are manifestations of Trumbo’s committed leftist politics.

Form and Function of the Fetish in Disavowal

I mentioned earlier the paradigmatic formula for psychoanalytic disavowal: “I know well, but all the same…” originally formulated in Octave Mannoni’s Les Temps modernes (1964). In Alenka Zupančič’s Disavowal (2024), however, she makes a qualification regarding the function of the fetish in disavowal:

The fundamental trick of the fetishist disavowal is that it transfers the disavowed belief (the ‘but all the same’ part) to an object — fetish — liberating the subject from all forms of unconscious belief … I am free from every belief, even unconscious ones, because it is my fetish that believes for me. Whereas the phrase ‘I know well, but all the same’ is the trade mark or the signature of disavowal, a fetishist will never say ‘but all the same’, since ‘his “but all the same” is his fetish.’ (24)

We can follow this idea through into Tare’s return to his hometown, showing off his collection of English dueling pistols.

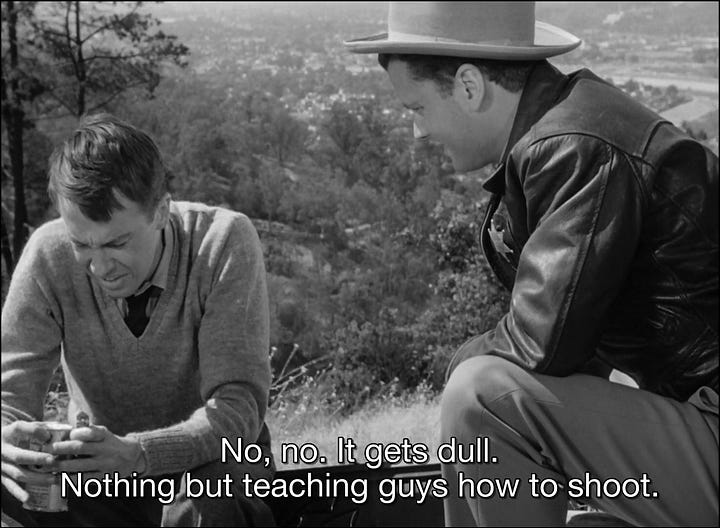

It’s no accident these are relics, divorced from their context as dueling pistols — there are no duels to be had — and even their cultural context — English, rather than American. Every activity Tare describes separates him from the primary function of guns as tools of killing. His return is from a career as an army shooting instructor, and the possible path he sees ahead is working for Remington, a gun manufacturer, as a demonstrator.

He will teach how to shoot the guns, or show how well the gun might shoot in the hands of an expert, but exculpates himself from any culpability of the killing that’s done as a result of what he is able to teach or demonstrate. His attachment to the fetish is the mechanism through which he disavows the outcome of which he could be proximate cause. And it’s through the spate of robberies and their outcome that he comes to be disentangled from his fetish, and, in turn, no longer capable of the disavowal that sustains him.

Gun Crazy’s Continental Romance

In addition to Tare himself, there is also the question of his relationship to Starr, who he marries at a roadside chapel early in the film. It is decidedly un-Lacanian, as Tare describes them of going together “like guns and ammunition.”

But this is not to say their relationship is not French, with the same kind of doomed love affair that would be the blueprint for films like Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960). Some attribute the adage, “all you need to make a movie is a girl and a gun,” to Godard, suggesting this is the lesson he learned from Gun Crazy. As it turns out, the line is more likely from D. W. Griffith, but ends up out of the mouth of Godard by way of a 1966 Pauline Kael essay.

Regardless of the quotation’s origin, Gun Crazy indeed proves it. The analogy between Tare and Starr’s romance and guns and ammunition is layered, as the gun exhausts and divides the ammunition into bullet and shell casing with the ignition of the gunpowder. Tare, too, is divided by the other, Starr, with whom his encounter seems cosmically ordained. It is, at least, ordained by Lewis and Trumbo who, like their star-crossed couple, come together to create an explosion.

Gun Crazy screens at Boston’s Brattle Theater on May 26th, Memorial Day, at 12pm and 4pm.

Nathan Fielder Acts Like a Horror Movie Character in “Washington”

When I wrapped up my viewing of “Washington” last night, I had that same sort of feeling that comes with many penultimate episodes of prestige TV. There is some necessary setup, some ideas that need to be threaded through more delicately for the final, forthcoming payoff. The episode is as funny as the show has ever been, but it also drew the camera back for some self-reflection. The show is always deconstructing itself, but this inventory was a little more earnest as Fielder looks back on the supposed impact of The Rehearsal’s (2022) first season and its reception as a representation of autism.

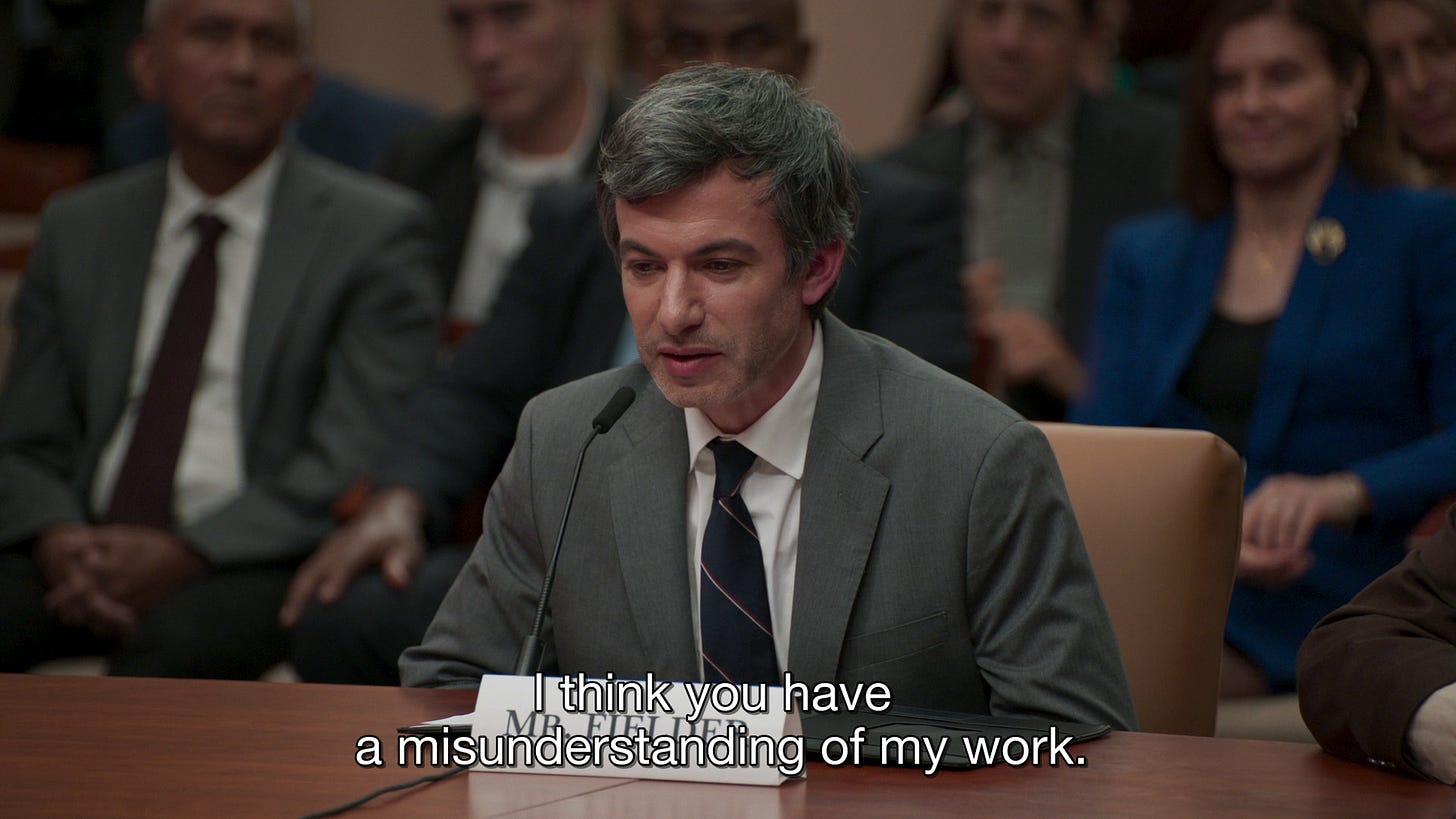

Fielder flirts with the idea of his own potential autism diagnosis. He stumbles through two slides of the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test and tries to distance the act of rehearsing from something only an autistic person would benefit from. His circuitous path to the role of autism “thought leader” leads him to a meeting with Congressman Steve Cohen (the actual guy). He blunders though the meeting, adding a put-on sense of ill-preparedness that the audience is supposed to think is the result of Fielder’s not rehearsing for the meeting.

Fans have noticed both the diegetically expressed refusal to rehearse and the greater meta-textual choice for Fielder to pretend to be unprepared for his meeting. Some ask the simple question: “why?” But asking why Fielder intentionally appeared unprepared at his meeting is like asking why the character walks down the dark hallway alone in a horror movie. There is no movie otherwise, and there is no TV show without Fielder messing this up. What kind of climax is Congressman Cohen shaking Fielder’s hand and saying, “okay, we’re going to have every pilot follow a character description.”

Even the best, most prepared presentation would have a hard time convincing someone assigning pilots and first officers the roles of “Captain Allears“ and “First Officer Blunt” would meaningfully reduce aviation disasters, even if that someone concedes pilot and co-pilot communication issues are a significant cause. No one watching The Rehearsal should lose sight of the fact that it is a TV show, Fielder himself anguishing over the documentary and comedy cross-purposes in “Gotta Have Fun.”

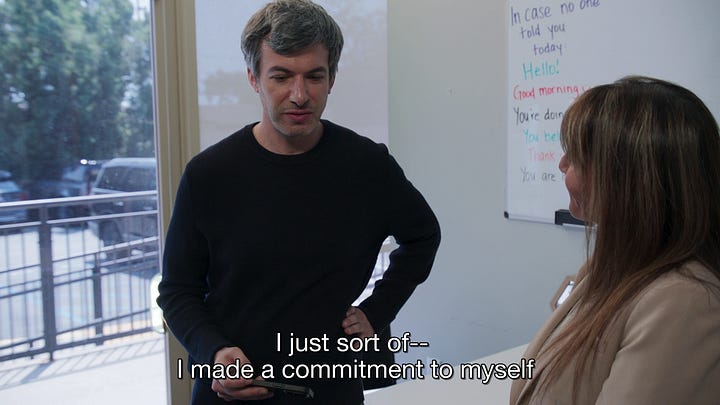

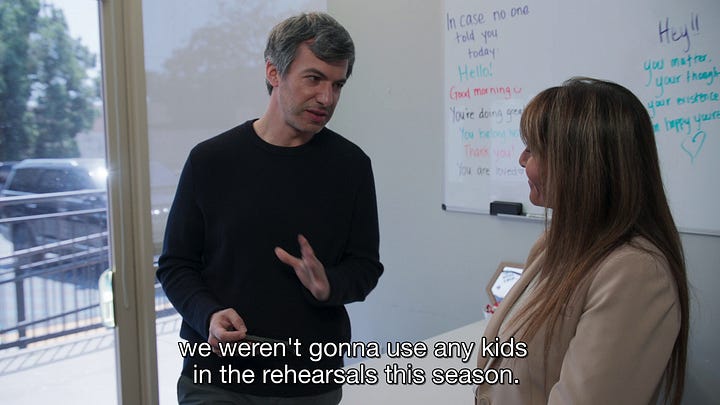

Regardless, Fielder fuels the speculation about his personal life and deeply held convictions. In his conversation with Doreen Granpeesheh, one of the more ostensibly revealing confessions is his aversion to using children in The Rehearsal’s second season.

This seems to be, in part, a confirmation of what “Pilot’s Code” implies with Fielder taking on the role of Sully Sullenberger with the required contrivances to give him a child-like experience as opposed to the observation of child actors playing out Sully’s life.

Even as the tension of the Fielder in front of the camera and the Fielder behind it grows, and the script leads away from what the camera shows, these two Fielders will always occlude the possibility of a “real” Fielder, one who would or would not be diagnosed with autism, one who may or may not have strong feelings about using children in his television show, one who does or does not sincerely want to reduce the number of aviation disasters more than they want to make good TV. This is no more obvious than in Fielder’s rehearsal with the Congressional Subcommittee on Aviation.

In the course of the rehearsal, Fielder decides to tell an obviously terrible joke about masturbating on public transit. When no one laughs at the jokes, he asks the actors that make up the Congressional Subcommittee’s audience, “why?” He instructs one actor, Troy:

You’re not supposed to laugh. I mean, you’re not supposed to do anything. You’re just supposed to act like a human, you know? … So, if you find something funny … just go for it.

He then addresses the audience as a whole, “We’re all playing like human beings, right? So, if you as a human find something funny, it’s okay to laugh.” Afterwards, the group, previously silent, collapses into hysterical, theatrical fake laughter. Fielder notices:

I just don’t want anyone to force a laugh. So, if your, you know, if your body naturally wants to laugh, just make the sound that that would make. But the fake laughs aren’t really helpful ‘cause I’m trying to figure out what works and what doesn’t.

No matter how much one might want authenticity in front of the camera, the camera’s gaze and the instruction of the director will always supersede any earnest expression of feeling. When Nathan is or isn’t performing, we will never know.

Weekly Reading List

The Charlotte Hornets’ local broadcast announcer, Eric Collins, is way too good for his team to be so bad. Adam Silver, give the Hornets the first pick in the draft. This team hasn’t made it to the conference semis since 2001. What are we doing here?

Things didn’t work out for the Celtics but this remains one of the best piece of promotional interview material the team has ever produced.

Yet another fascinating deep dive into the history of competitive Magic.

Editor’s note: the fact that I did not answer or even reference the title of this week’s newsletter is not an oversight. Keep both eyes open.

Until next time.