Issue #381: Betting Your Life on The Rehearsal

The fact that a “youtuber” or “content creator” will ask someone to “like, share, subscribe” is so widely understood that I wonder if there’s a degree to which saying it is superfluous. The expression of the sentiment, a request or demand for a subscription, has certainly become passé to the point those who might benefit from such an injunction think twice about saying it. I feel that way. So, generally, you infrequently see more elaborate requests for support outside of the “subscribe” button at the end of the letter.

But it’s something I’ve been considering. First, when someone recording a video makes this request, it can be a little presumptuous. Sure, there’s a formula that one tends not to diverge from. But Kenji Egashira, a professional Magic: the Gathering streamer known as NumotTheNummy, has taken a slightly different approach to his prerecorded youtube videos. He says, along with the usual spiel, “if you don’t subscribe, I hope to earn your subscription today.” Maybe this is too obsequious, but I prefer some level of acknowledgement that the person on youtube is hoping the subscription relationship is symbiotic. You subscribe because you like whatever you’ve subscribed to.

There are also some economic realities of me writing the newsletter that I think are obvious, and I’ve certainly mentioned before, but maybe not everyone knows. I work a 9 to 5 non-academic office job. There’s nothing really wrong with my job other than the things wrong with every job. I would rather write more, be able to refine each newsletter more, produce more exclusive stuff for my paid subscribers. But I need to derive a certain income from writing to be able to do that. Frankly, I don’t think that day will ever come. But if you are a paid subscriber, or you become one, that’s what you’re supporting.

As far as “earning your subscription,” I hope I am doing that — paid or “free.” No level of Paradox Newsletter subscription, if you really read it, is free. Time isn’t cheap. And the newsletter asks something of you, to come along for a ride to learn about things you sometimes might not care about, sometimes might be confused by. I’m by no means an evangelical for the things you don’t care about nor an expert pedagog about the things that confuse. My hope is that the newsletter, at its best, puts things into your head that shake around and, perhaps, enriches something about your life in a way that might not be immediately obvious.

So, thanks for your support. Consider becoming a paid sub because this publication has untraversed horizons that need some money to be realized. And consider, if you have a friend who might like what I’m doing, telling them about it.

“The least experienced person licensed to fly a 737 in North America”: Fielder’s Rejection of Self-Knowing in a Triumphant Rehearsal Finale

The Rehearsal (2022) ends on a note that feels — dare I say it? — sincere. Sincere not in the fact that it conveys a feeling a person has, but in the sense that it conveys a feeling its audience has felt. The show is hard to read because it is at odds with itself, but the question of the FAA’s stringent mental health policies ascend to absolute apotheosis of the show’s concerns in the final episode. Ultimately, though, the show is not about any particular issue with aviation or pilots. If The Rehearsal’s first season was about one’s relationship to others, the second is about one’s relationship to oneself.

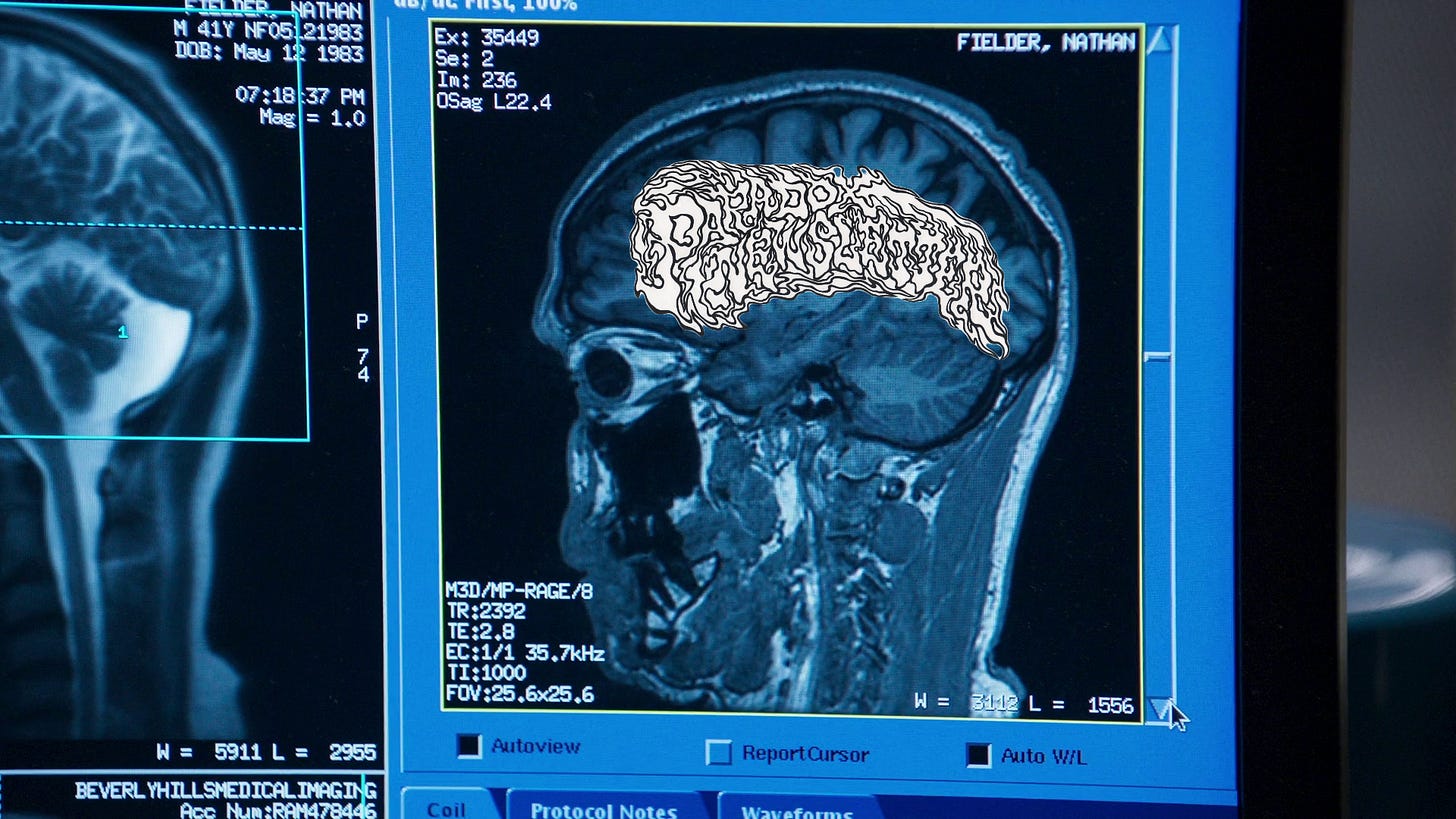

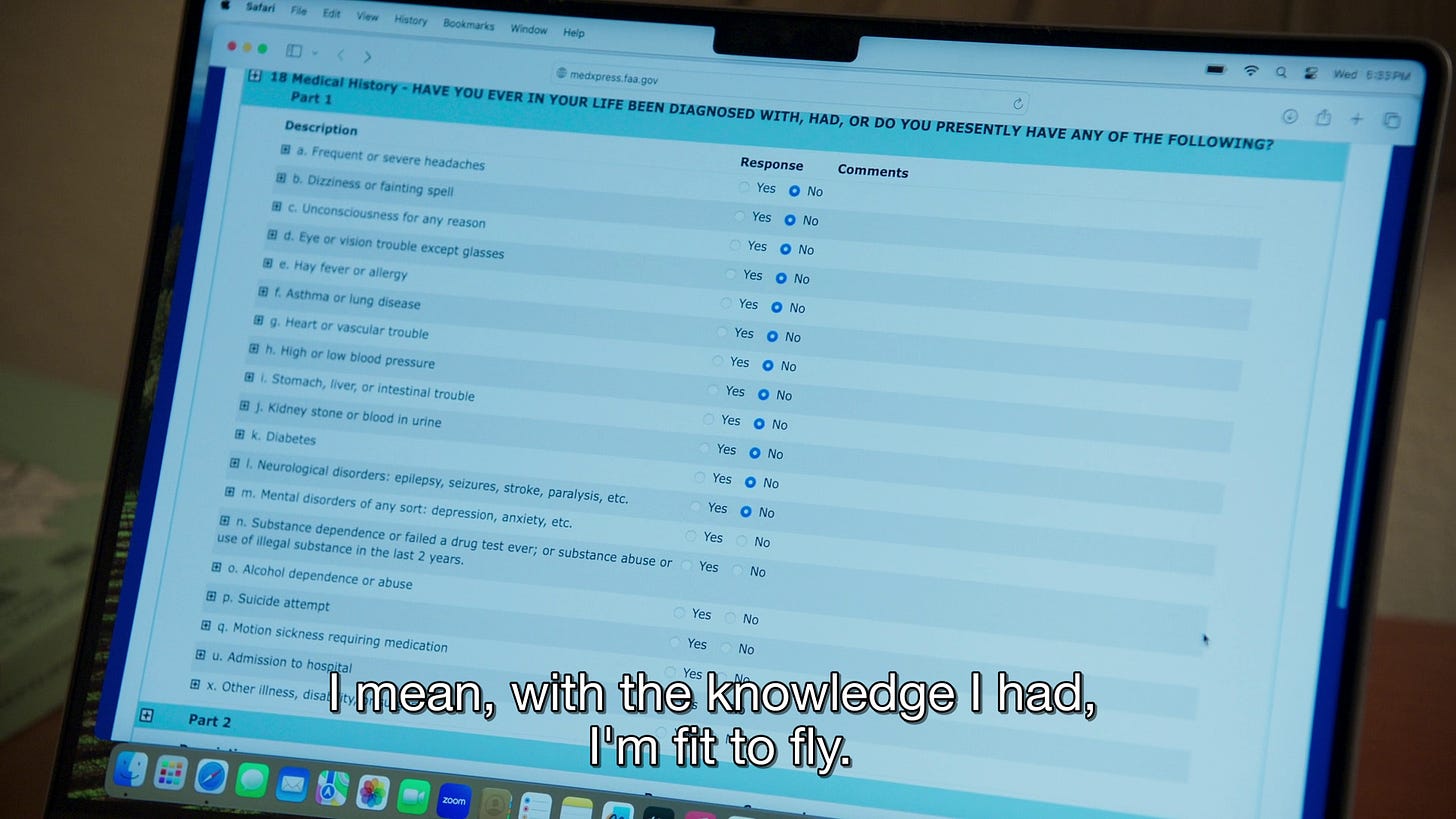

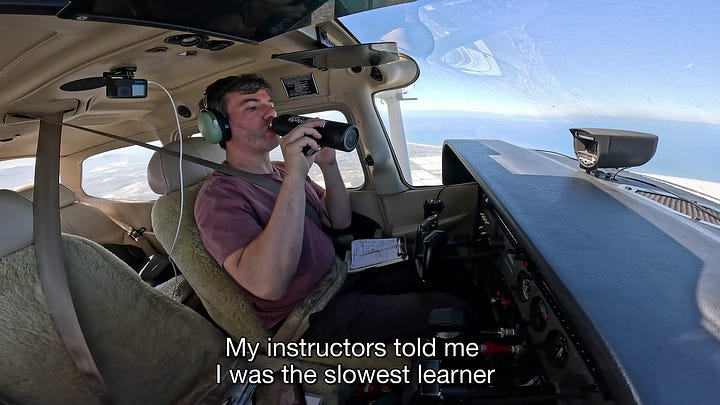

In the course of the episode, Fielder recounts his two year journey to become a licensed commercial pilot with 737-type rating. He also comes face to face with the season’s villain, the FAA’s medical clearance form. He agonizes over his responses, receiving an “fMRI” to potentially identify any relevant conditions. Ultimately, though, he opts to indicate his fitness to fly even without receiving the results.

“With the knowledge I had, I’m fit to fly”

There is a double meaning in Fielder’s statement in the screenshot above, the statement that also titles this section. Licensure for piloting is about knowledge, tested practically and understood through the achievement of certain benchmarks. Having a certain level of experience, measured through flight hours, indicates that one knows enough to fly under certain constraints. These constraints continue to relax, as Fielder discusses obtaining no less than four certifications for different types of aircraft. Fielder, at the FAA’s implicit pressuring, also rejects a certain kind of self-knowledge related to his mental health and neurotypicality. The knowledge that FAA medical authorization requires one to avoid could otherwise help a pilot navigate their life. Likewise, there are cascading effects that Fielder most emphatically discusses in his re-enactment of Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger’s life — the possibility that a pilot can’t express their feelings or, even more concerning, address symptoms of mental health issues in a straightforward fashion. Instead, the pilot must express those symptoms in another way and can’t utilize medical intervention for their treatment. Thus, we have music as the best medicine available according to the logic of The Rehearsal, Fielder talking solace in “Bring Me to Life” the same way he imagines Sully doing.

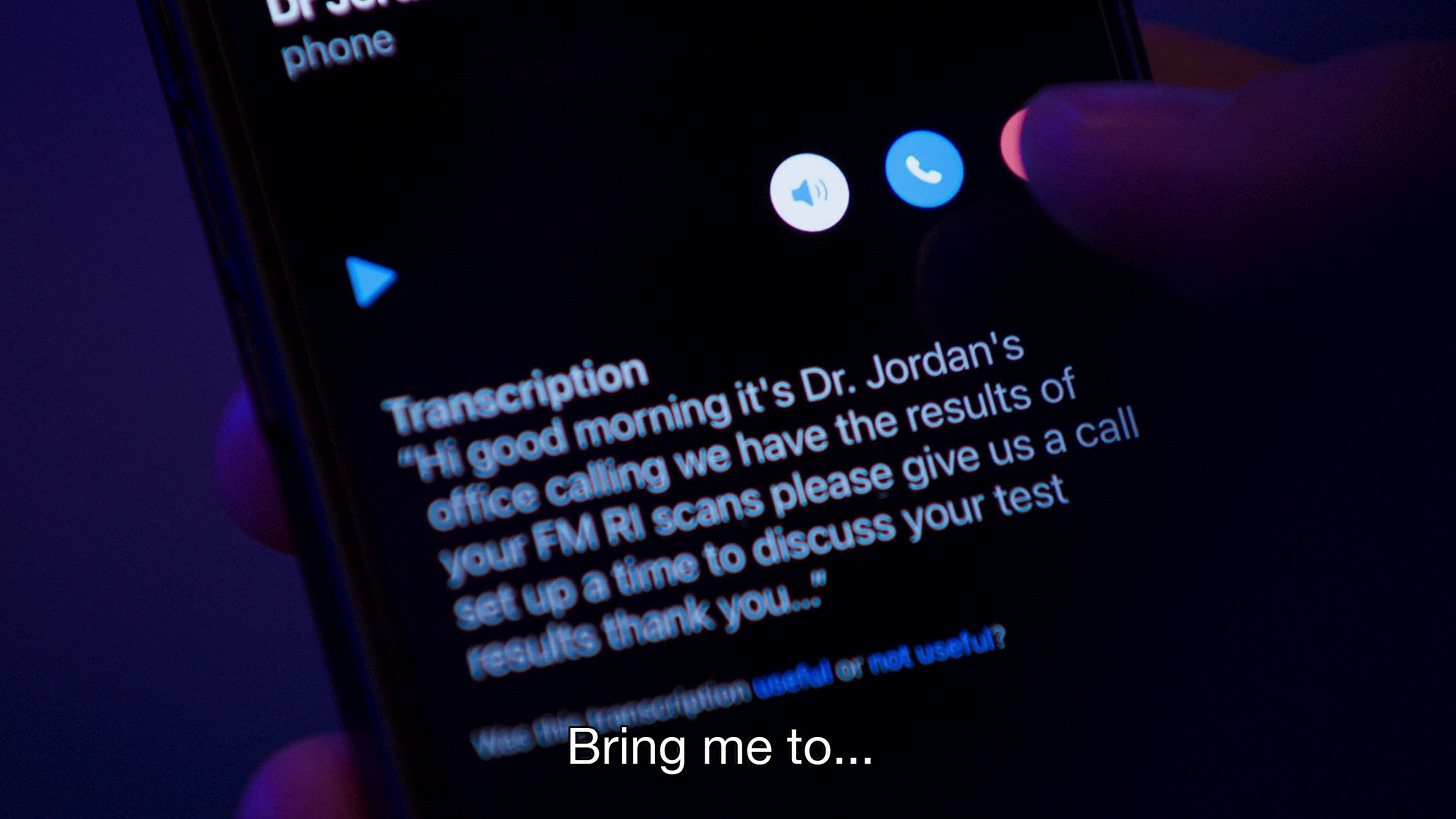

Fielder takes things a step further than he imagines for Sully, though. Sully, in the reenactment, has a sense that there is some symptom to be alleviated. He does so using music and whatever else is obscured by the idea of finding “ways to cope” as it appears in his autobiography. Fielder has to deny the possibility of a symptom altogether. There is, of course, the fact that this is a television show about a licensed pilot, thus everything Fielder says would be subject to scrutiny that could impact his certifications. But on screen, Fielder shows only what the audience can conclude is sincere at least at the level of his filmed persona. He deletes the voicemail from Dr. Jordan that might reveal and officially document diagnoses that could result in his medical clearance being revoked.

Taking a wider view of the show, it is in some ways a parable about the pain of learning about oneself. There were times when I read the series as a polemic about the FAA’s draconian policies related to mental health and neurodevelopment disorders. In retrospect, it seems to me The Rehearsal’s second season is more invested in the greater truth about human experience rather than the unintuitive policy. This policy encourages both lies by omission and self-deception, imposing an ignorance on the subject about their experience. There are horizons one can’t cross, things one can’t know, in the interest of prolonging one’s career as a pilot. But knowing about one’s anxiety, depression, or autism doesn’t resolve the symptoms that cohere in these disorders. Fielder is confronted with the same kind of disquieting self-examination with regard to what he calls “a bit of a gambling problem,” which he specifies only presented an issue for him when he was younger. Fielder cannot ask too many questions or think too deeply about it, accepting the circumstance he can’t change: his 737 flight education will occur in Henderson, Nevada.

Similarly, Fielder’s pilot’s license becomes more valuable to him as the episode goes on. He overcomes hardship to fly and is satisfied by his capability as a pilot. He repeatedly asserts his authority as a pilot, despite his relative inexperience. For Fielder, accepting the descriptor of “autistic” or “clinically anxious” means relinquishing “pilot.” While he says to John Goglia he doesn’t have to worry because flying isn’t his career, his identity is even more valuable.

The identity Fielder clings to, that of the pilot, is opposed to certain kinds of self-knowing. This rejection happens at the intersection of bureaucracy and liability, insulating the FAA from certain kinds of blame, legal exposure, and insurance burdens. But to read this prescription of knowing oneself more benevolently, to accept the FAA’s schema related to self-knowledge in the way Fielder seems to accept it, such a line of thinking requires some condition for this prohibition outside the legal and commercial frameworks. One possible condition relates to the shortcoming of diagnosis itself. Knowing one’s precise illness or condition often opens the possibility for treatment, but sometimes treatment or intervention is impossible. This form of knowledge may be true in a non-trivial epistemic sense, but it falls short of serving the knower. As Nietzsche writes in The Gay Science (1882):

We call it ‘explanation’, but ‘description’ is what distinguishes us from older stages of knowledge and science. We are better at describing — we explain just as little as our predecessors … The specifically qualitative aspect for example of every chemical process, still appears to be a ‘miracle’, as does every locomotion; no one has ‘explained’ the push. (Nauckhoff trans. 113)

Though not at all charitable to scientific discourse, Nietzsche’s argument here is that the creation of terminology that gives a more detailed account of some scientific process does not substantially explain what occurs. We might also read Fielder’s rejection of self-knowledge and its shortcomings as a Lacanian gesture. From Television (1981):

I always speak the truth. Not the whole truth, because there’s no way, to say it all. Saying it all is literally impossible: words fail. Yet it’s through this very impossibility that the truth holds onto the real. (3)

This tenuous grip of the truth to the Lacanian Real is why Lacan insists truth can only be “half-said” or mi-dire. If the seizure of truth means an encounter with the unsignifiable Real with little to show for it, it’s no wonder Fielder opts for his solitary piloting career instead.

“Based on what?”

The show ended up being less about the constraints of acting than I expected, instead opting to conclude that it is pilots who are forced to act in the course of their official duties regardless of whether they adopt the Captain Allears and First Officer Blunt personas. The idea of acting still serves a critical role in the finale, though.

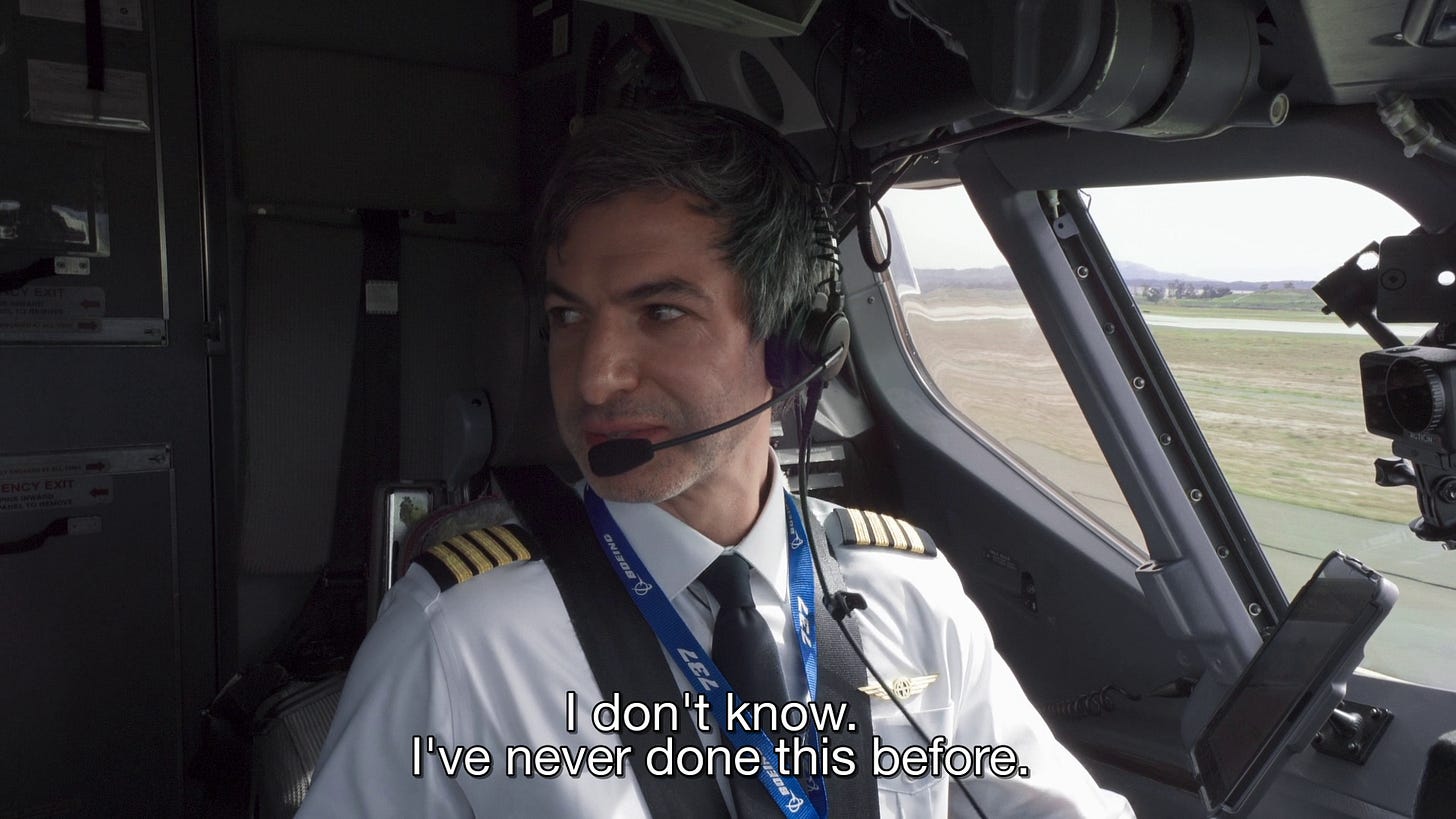

Fielder repeats he is a pilot, insisting upon it at every opportunity. As he undergoes his training, it’s clear that he comes to like flying. His attachment is both to the act itself and the codes — pilot’s code — that governs one’s behavior as a pilot.

Perhaps acting’s value is to relieve someone from the burden of self-knowing, allowing them to introspect something external to themselves and behave in accordance with the role. This is precisely what Fielder gets out of the identity of pilothood, he can act like a pilot, but not because he is acting professionally, because he is one. In that sense, we return again to the question of performed sincerity from “Star Potential.” An identity, something you name yourself, is a role. It is outside of the individual, imposed or afforded.

An identity one can adopt or a role than can play covers over ambiguity and uncertainty, “not knowing what’s going to happen and fear of what could happen,” the source of anxiety according to Evanescence’s Amy Lee, a statement with which Fielder agrees.

But Fielder is unique in the degree to which he can control a situation. Just like every episode this season, and through the entirety of his career, Fielder’s bits are part psychological test, part moral trial. The entire opening of the episode is dedicated to him disclosing his plan, to fly a 737 for the first time as a novice pilot, to the actors who will make up the plane passengers. He concludes the montage with an emphatic question from one of the actor-passengers, “how many people have outright said, ‘No, I don’t wanna be a part of this’?” to which Fielder replies, “none.” Yet another testament to what people will do to get on camera.

His reality TV torture chamber (and, as sublime as a season of TV The Rehearsal is, I feel like I cheapen the show losing sight of its indignant origin) is no more merciful for his co-pilot, Aaron

By having the aerial photography plane fly very close to their 737, Fielder attempts to create a scenario that will occasion criticism from Aaron. Just like with the other pilots, he understands what buttons to push to elicit the best response for “good TV.”

“You’ll never know it’s not there”

There’s no one like Nathan Fielder, but exceptional people don’t always make exceptional work. In this case, we are fortunate to be able to reason his state of exception not from a medical diagnosis, but from the quality and consistency of the work he’s contributed to the culture. This superlative is not an exaggeration, either, given the scope of what this finale offers: a first time flight from the least experienced pilot in North America licensed to fly a 737 with a cabin full of passengers. “Stunt” doesn’t begin to do it justice. And this is to say nothing of the sampling of normal Fielder cranks the episode showcases, like Dr. Jordan and a mechanic who tries to lease Fielder a 737 full of birds’ nests.

Here’s to a season three of The Rehearsal. Or whatever Fielder does next.

Weekly Reading List

https://brattlefilm.org/film-series/noir-city-boston/ — I guess this is technically an event listing, but you can read the synopsis of all these movies I’m going to see in mid-June. The Brattle is selling tickets for the entire series now, including a pass that gets you into every screening.

More on this game next week.

Until next time.