Issue #383: Blowing Up the Spot in Vermont

I think the sign of a good writer, or at least a good thinker, is the capacity to come up with a punchy, provocative phrase. Though it might be wrong to credit Kant with this, in “What is Enlightenment?” (1784) he quotes the Society of the Friends of Truth, “Sapere Aude,” which translates to “Dare to Know.” I think that’s pretty good. And fitting for a milieu wherein intellectuals are marshaling the gumption to produce knowledge through their own capacity for thought. To add a little texture to this thesis, Kant writes:

Rules and formulas, those mechanical aids to the rational use, or rather misuse, of his natural gifts, are the shackles of permanent immaturity … Consequently, only a few have succeeded, by cultivating their own minds, in freeing themselves from immaturity and pursuing a secure course.

When Foucault responds to Kant in 1984, in his own essay also titled “What is Enlightenment?”, he shows his penchant for rousing turn-of-phrase:

Yet that does not mean that one has to be “for” or “against” the Enlightenment. It even means precisely that one must refuse everything that might present itself in the form of a simplistic and authoritarian alternative: you either accept the Enlightenment and remain within the tradition, of its rationalism (this is considered a positive term by some and used by others, on the contrary, as a reproach), or else you criticize the Enlightenment and then try to escape from its principles of rationality (which may be seen once again as good or bad). And we do not break free of this blackmail by introducing “dialectical” nuances while seeking to determine what good and bad elements there may have been in the Enlightenment. (313)

I find his idea of “break[ing] free of this blackmail” particularly evocative, later echoed by Žižek in Against the Double Blackmail (2016). Regardless of what you think of the two poles of blackmail Žižek writes against — open boarders and isolationism — it’s hard to deny the title is exciting.

But the Foucault quotation shows more than this capacity for provocation I value. Despite being a systematic thinker — in The History of Sexuality (1976), Foucault connects relatively obscure and isolated examples of sexual behavior to his contemporary context — he rejects any mode of thought that would reduce his intellectual tradition to one particular classification. In this case, he makes a simple point. The Enlightenment is complex and may confront a thinker with a myriad of principles, underlying assumptions, and outcomes that said thinker might endorse or reject in a wide variety of combinations. One does not simply have to endorse or reject every aspect of a broad intellectual shift like the Enlightenment. Indeed, broad endorsement or rejection is exactly what someone should not do.

Perhaps I have chosen the wrong aspects of Kant and Foucault to valorize. After all, I have picked some of the most important thinkers in the history of philosophy and asserted their aphorisms are indicative of their intellect. But, I must admit, their contributions to intellectual history are more evident from larger excerpts and deeper reading as opposed to scanning their most notable quotations. Still, flourishes are welcome.

Vermont Vacation Dispatch

If I am reading culture correctly, Vermont has the reputation of being a vacation destination for petit bourgeois enjoying “rustic charm” in the confined temporal space of a weekend. Vermont’s aura comes, in part, from its being represented by Bernie Sanders in some form or fashion since 1981. First, as the Mayor of Burlington, then as Vermont’s Representative in the House beginning in 1991, and today as Vermont’s U.S. Senator beginning in 2007. As much in Vermont as anywhere, millenial vacationing comes with its unique sense of contrition. Even in southern Vermont, close to Western Mass and Upstate New York, the country store institution is slowly transforming into wood-paneled Erehwons.

It’s unclear to me if Vermont has hit the inflection point of tourist oversaturation. Just like the circumstance dramatized in Hamaguchi’s Evil Does Not Exist (2024), some regions benefit from modest tourism but would have their way of life irrevocably transformed if the density of tourists increased. And what one values about a place like Vermont is precisely that which would be destroyed by an overwhelming flood of tourists and development to accommodate them. In Dorset, Pawlet, Rutland, and Manchester, the signs of such changes are slow. But you can buy $55 kitchen scissors imported from Japan in a combination garden and coffee shop, Mettowee Mint. At the Dorset Farmers Market, across from H.N. Williams, family farms are selling sausages and vineagar tonics with sophisticated branding and packaging.

And, of course, there’s the hiking. There are a lot of hikes to waterfalls. The Appalachian Trial begins in Vermont in Stamford, through Manchester and Shrewsbury. You can see signs of that too — hiker’s hostels and signs for the trail.

As a vacation destination, Vermont lives up to the hype. But my enthusiasm is always matched with caution, caution that I hope will preserve what is great about a place I like to visit.

Habeas Corpus: What It Does, What It Means

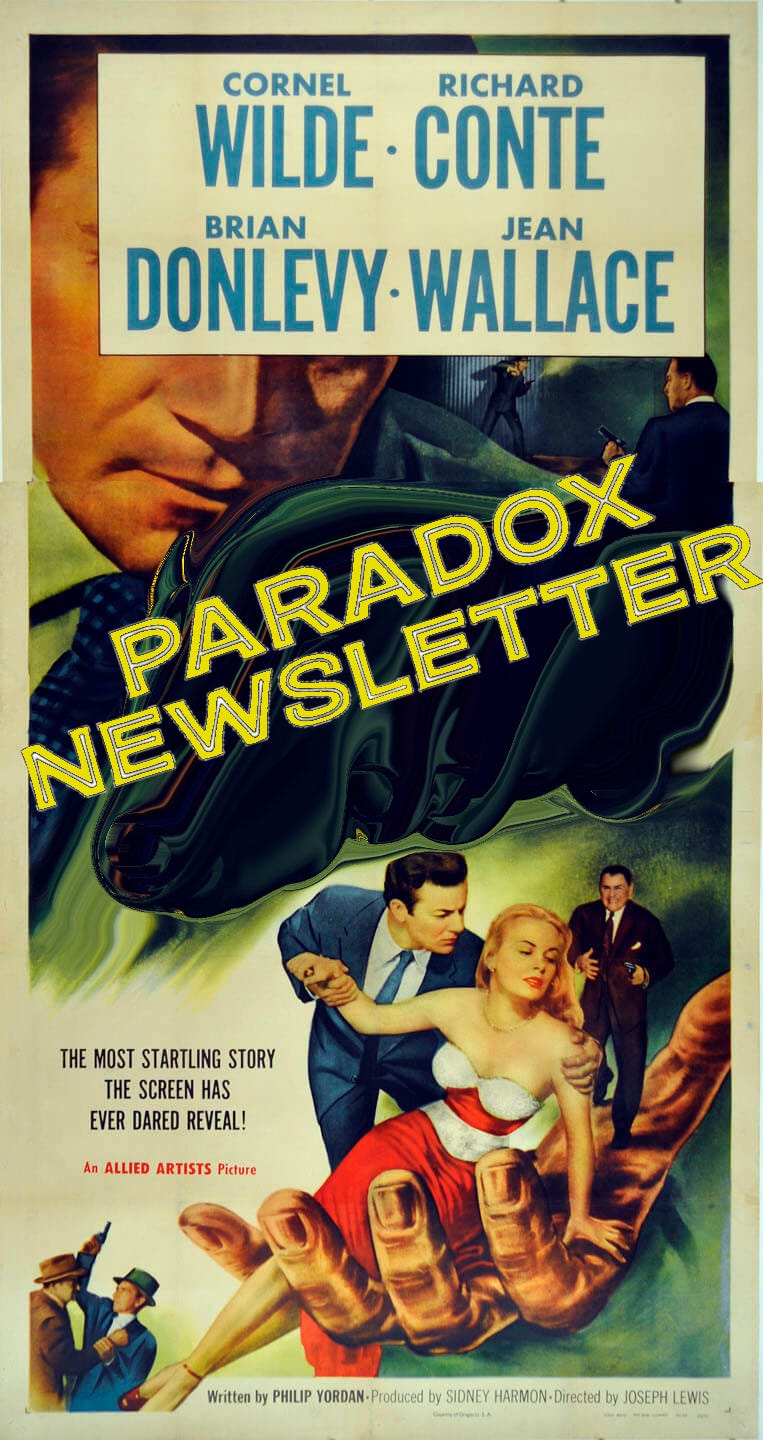

In The Big Combo (1955), there’s some dialogue in the early part of the film about the legal procedure of habeas corpus. Leonard Diamond (Cornel Wilde) asks his colleague Sam (Jay Adler), “You know what ‘habeas corpus’ means, Sam?” to which Sam replies, “I know what it does.” What it does is prevent illegal detention or imprisonment, calling upon the law enforcement apparatus to prove their detaining of a person is lawful. Originating in the English courts, the U.S. Constitution codifies habeas corpus in Section 9 of Article One: “The privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it.” The suspension of habeas corpus is something the Trump administration has explored back in May, relating to their detention and deportation of alleged undocumented immigrants. Typically, the suspension of habeas corpus means the institution of martial law, as was the case in the course of the Civil War, in South Carolina during 1871, and in Hawaii immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.

As for what habeas corpus actually means, Diamond goes on to explain, “It’s Latin. It means “You may have the body.” Diamond’s resignation to surrender Susan Lowell (Jean Wallace) to Mr. Brown (Richard Conte), pointing to the disjunction between “the body” and some other thing — mind, spirit, or soul. Lowell is a kept woman, symbolically Mr. Brown’s Jane Eyre compared to the corresponding Bertha Mason, Alicia Brown (Helen Walker) who is imprisoned through Mr. Brown’s machinations. Lowell’s position means possession of her body, rather than her mind, is what is at issue for both Diamond and Mr. Brown. His imposing possession of bodies is not something that can be subverted by habeas corpus and, indeed, in The Big Combo legal protections function as handmaidens to criminality. Like any good film noir, Diamond must reject the bounds of written law, devoted to a higher set of principles, and confront judicial hypocrisy in the course of foiling Mr. Brown.

In our contemporary U.S. context, where the right of habeas corpus is imperiled, there is a similar appropriation of the law to harm society as a whole. Law is instrumentalized as the very tool that subverts its spirit. Instead of using habeas corpus, Trump may avail himself of the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act which Lincoln used to suspend the protection in the single instance of martial law being federally imposed in U.S. history. If Trump uses his authority in this way to respond to the ongoing protests in Los Angeles in opposition to ICE, it is self-evidently not a necessity in the face of extreme imperilment to the population. Instead, it is an effort to make Trump’s authoritarian power more robust and subvert the First Amendment. Moreover, despite the consistent deferral to the rights of states on issues like abortion, Trump’s deployment of ICE in states like Massachusetts and California is clearly intended to subvert the state’s authority regarding treatment of undocumented immigrants.

While The Big Combo is thought-provoking in its juxtaposition of the body, as in corpus, and the mind, the situation in the United States will (unfortunately) not be immediately ameliorated by philosophical inquiry. The body and the rights associated with it are precisely what Trump seeks to make contingent on citizenship or membership of a dominant identity group. Without habeas corpus, law enforcement is not accountable for the legitimacy of its detention of people. This is a condition of imperilment uncommon in U.S. history, and unprecedented as it relates to an aspiring tyrant’s designs on subverting the U.S.’s Constitution and values.

Weekly Reading List

https://www.lacan.com/badeight.htm — Revisiting Badiou’s “Eight Theses on the Universal”

Jennifer Pan, author of Selling Social Justice (2025), offers a historical overview of the relationship between so-called “DEI” programs and working class history.

Until next time.