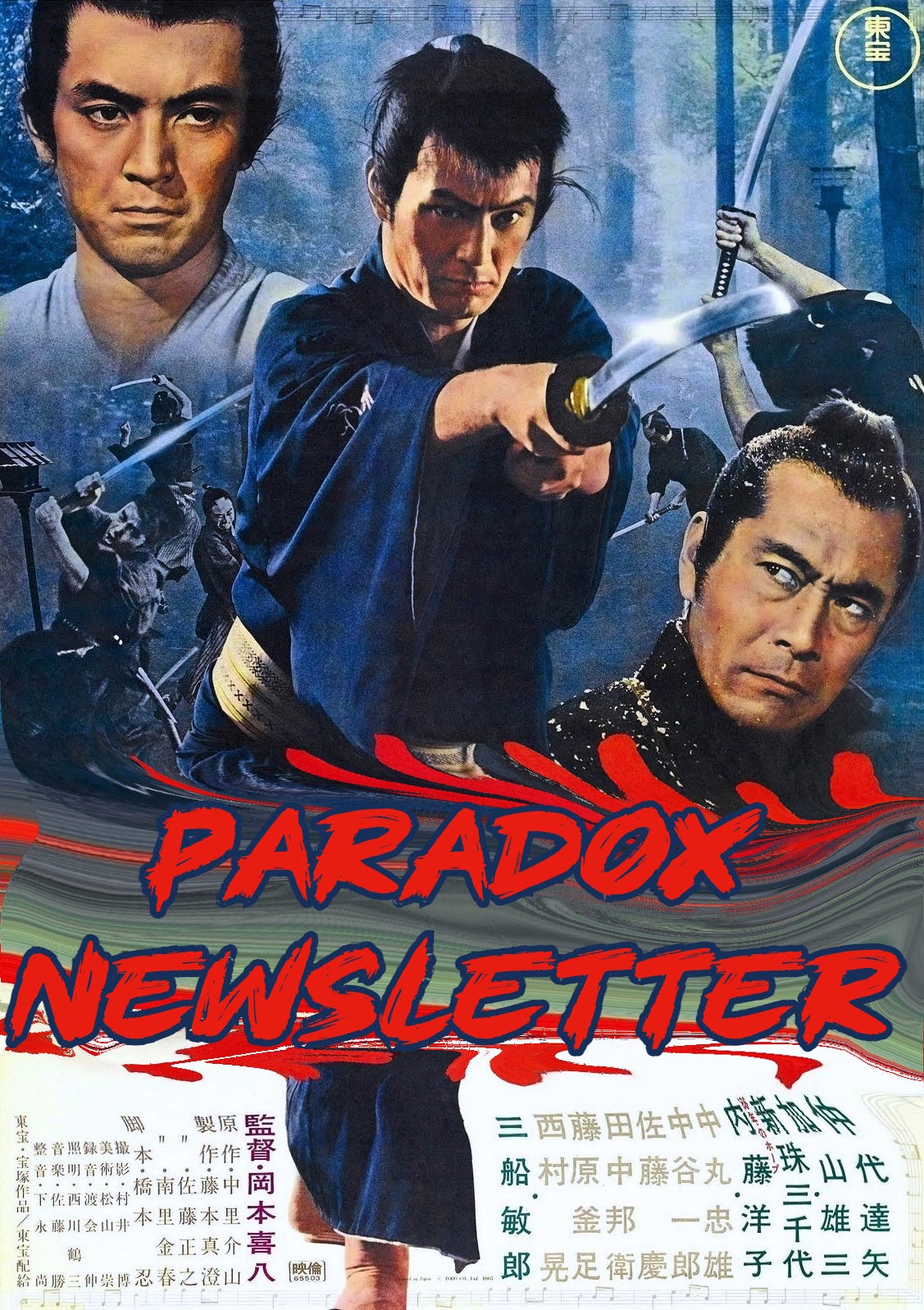

Issue #386: The Case for Tatsuya Nakadai as the GOAT

There are a few reasons why this newsletter is only a modest success. Among them, I’m terrible at self-promotion. Maybe nobody likes promoting themselves. Whether it’s common or not, though, I experience an insurmountable repulsion from most methods. Excessive self-promotion is both obnoxious and undignified. It draws attention to the work’s shortcoming, namely that it is not being read without prompting.

It also serves as the unconscious root of forgetting. I haven’t posted about my imminently forthcoming movie marathon since May. Two months worth of promotion time, squandered. But, it’s happening!

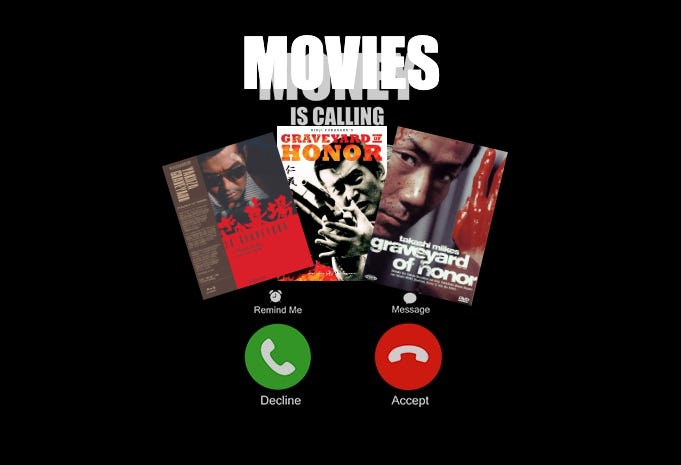

It is time to be seated in front of your screen and watch three yakuza movies on Discord with all your new friends. There’s discussion to be had after the films. Like when I go to Jaho after seeing a Hong Kong action movie.

The Discord link goes out automatically to paid subs.

If you have questions, don’t hesitate to email. Hope to see you there.

Evil in Kihachi Okamoto’s The Sword of Doom

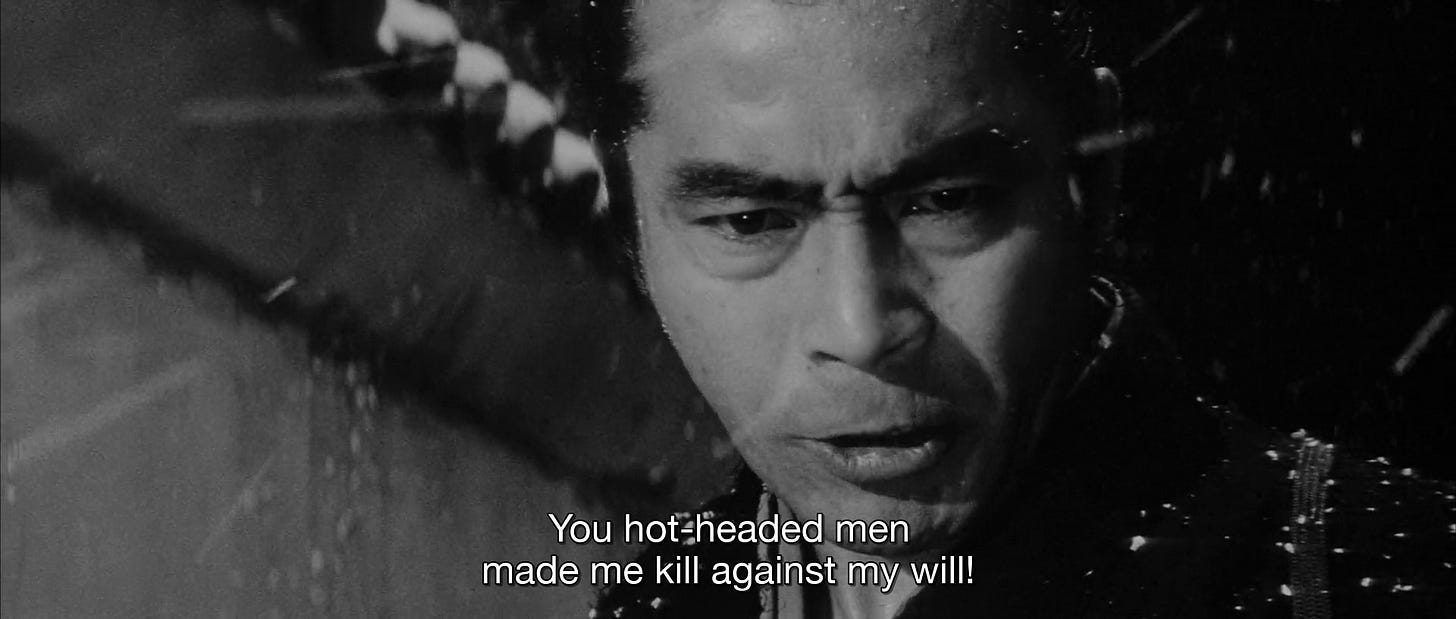

David Kornfeld, the head projectionist at the Somerville Theater, is my favorite fixture of the Boston independent film scene. His film introductions rarely miss. His lead-in to The Sword of Doom (1966) had to be seen to be believed. It involved him demonstrating Ryunosuke Tsukue’s (Tatsuya Nakadai) sword technique with an umbrella. Pointing the umbrella downward, as Ryunosuke does in his sword fights, Kornfeld explained, “you see, it’s a feint.”

Ryunosuke’s style is described as “empty” in the film, with Geoffrey O’Brien identifying it more explicitly as mumyo otonashi no kamae in an essay for Criterion’s Sword of Doom edition. How Ryunosuke fights is critical to the film. It’s idiosyncratic, brutal, deceptive, effective. It flies in the face of convention. Ryunosuke’s father, Dansho (Ryosuke Kagawa) says to him at the film’s outset, “I don’t fully understand your sword form. You draw out your opponent. Then, in an unguarded moment, you cruelly…” As his father observes, Ryunosuke shows himself repeatedly to be sadistic. However, his cruelty also puts the lie to the notion of samurai honor, bushido. Swords are tools for killing and sword styles are methods of killing. Ryunosuke, then, represents the twisted but true reflection of the essence of what’s sublimated in the notion of bushido.

Tatsuya Nakadai seems to have made a career on playing manifestations of bushido’s hypocrisy. In Kill! (1968) his character, Genta, has forsworn the samurai class. In Harakiri (1962), presented with Sword of Doom at Somerville, Nakadai’s Tsugumo Hanshirō reminds the Iyi clan, “when all is said and done, our lives are like houses built on foundations of sand. One strong wind and all is gone” and “what befalls others today, may be your own fate tomorrow.”

Unlike Kill! or Harakiri, the condemnation of bushido in Sword of Doom is about raw violence more than hubris. Ryunosuke works as a member of the Shinsengumi, the Tokugawa Shogonate’s assassination corps, seeking to maintain power against the ascendant imperial court. The idea that any governing body would enforce high-minded ideas using violence is inherently contradictory and obscene. Many works that take the Bakumatsu period as their subject seize on this contradiction. A government that reigns in peacetime must disavow their use of violence in the conflict preceding that peace. And, of course, the Bakumatsu wasn’t a civil war but a “disturbance” or “dōran/どうらん –.”

Ryunosuke embodies this irreconcilable obscenity of that which is accepted in the name of establishing peace and rejected once peace is attained. He is the excluded queer remainder (No Future 4); the rejected, papered over necessity Johnny Rocco (Edward G. Robinson) embodies in Key Largo (1948).

What makes Ryunosuke unique within this paradigm is he is excluded even when his capacity for violence has value.

Kihachi Okamoto, The Sword of Doom’s director, is known for his capacity to make riotous comedies. But there is nothing comedic in Sword of Doom. It is an unflinching, brutal, ugly film. It is the ugliness accumulated over generations of violence, paraphrasing Okamoto, “Ryunosuke’s sins are inherited through the laws of reincarnation” (Smith 17). These sins, one imagines, were accrued behind a katana’s hilt.

Sword of Doom has a radical form in its expansive plot and abrupt conclusion. It also forces audiences to question whether or not Ryunosuke’s relationship to bushido and swordsmanship is truly as scandalous as it appears. The real scandal is the violence inherent in the supposedly refined, morally upright system of bushido.

The sword may be evil no matter who wields it.

Weekly Reading List

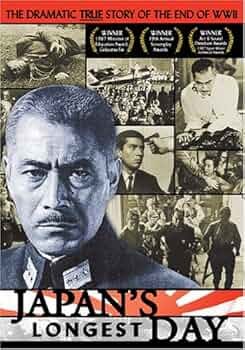

At Tom Mes’s impassioned recommendation, I am watching Japan’s Longest Day (1967) this week. Of Kihachi Okamoto’s films, I have only seen the two most notable, both of which I mentioned earlier: Sword of Doom and Kill! By all accounts, Japan’s Longest Day plays to Okamoto’s strengths of provoking thought through a thrilling plot. Supposedly, according to Mes, Okamoto’s films “are unbiased, apolitical, agenda-free, even if they unmistakably express the absurdities of war with every frame.” Mes goes on, “[Japan’s Longest Day] attempts to understand the motivations of the various individuals and parties involved without prejudging them.” Okamoto shows this dispassionate view in his treatment of Ryunosuke in Sword of Doom, though I think it would be a stretch to call the film “unbiased, apolitical, [and] agenda-free[.]” But Sword of Doom is not a polemic. Japan’s Longest Day sounds like it isn’t one either.

https://harvardfilmarchive.org/programs/floating-clouds-the-cinema-of-naruse-mikio — The Harvard Film archive will be screening rare prints of Naruse Mikio films from this weekend through November. From their description by Kelley Dong:

Because Naruse placed more narrative importance on the machinations of the inner life than on external circumstance, his films challenged actresses to embody the private act of thinking. Though hardly docile, the typical Naruse heroine is a thinker who observes more than she speaks—in Lightning, for instance, he and Takamine replaced lines with gestures. She thinks about life and the lives of others, and she feels the pressure of being thought about. As the protagonist of Sudden Rain (1956) exclaims to her judgmental neighbors: "I was criticized for not greeting others. That's just because I was thinking." And when empty promises—whether by an empire or a pathetic man—reveal disappointing truths, she finds strength by refusing self-pity. Though she may not immediately quit her job or leave her husband, through the repetition of her routine Naruse uncovers a slight but significant shift in perspective.

Instant classic from Sami Reiss

Until next time.