Issue #387: Breaking News on Graveyard of Honor 2002's Wardrobe

Leading up to this weekend’s movie marathon and partially inspired by Foster Hirsch’s great introductions at Noir City Boston, I wrote up some blurbs about Kinji Fukasaku and Takashi Miike along with their key contributors in Yakuza Graveyard (1976), Graveyard of Honor (1975), and Graveyard of Honor. I sent Erin the text and they did all the rest, choosing the six page mini-zine format, doing the layout, finding the pictures, fonts, etc. For an easier version to print, including a second page of folding instructions, you can go here. My printer is broken, so I couldn’t actually print them out. Fortunately my friend Garrett was more than up to the task across the country.

Why have I been doing these movie marathons? Well, they’re fun. It seems like the right amount of people show up every time. I like to program film. And, most important, I would like to create a shared archive of cultural knowledge among myself and friends who read this letter. This one goes down as a success, so I’ll probably do another in the winter. If you didn’t join in, you can read the program and watch the movies yourself. Both Graveyard of Honor movies are available on the Arrow streaming service. Yakuza Graveyard is more widely available. It’s on Kanopy and Fandor and a bunch of other streaming services I have never heard of.

As for the movies themselves? I loved them all. For me, what makes a truly great film is one I regard more highly the more I think about it. That’s certainly the case with all of these. Read on.

Cracking Knuckles, Balloons, and Dentist Appointments: The Ugly World of Fukasaku and Miike’s Yakuza Films

Talking about violence in film, Kiyoshi Kurosawa recounts an encounter after the release of Cure (1997) that led him to seek Kinji Fukasaku’s advice:

After a film of mine was shown, I was actually confronted by a woman, a total stranger. She rebuked me by saying, “Why did you make a movie like this? I have a child, but I can’t show this kind of movie to my child. Have you any idea what harm this movie would do to a child’s education?” And I couldn’t come up with a reply to dispute her point. So I told Mr. Fukasaku about this incident and asked him what he would have said to the woman if he were in my position. Mr. Fukasaku was calm as ever, as if such an incident were a daily occurrence, and answered me coolly, “What is this idea of education that gets shaken by a violent movie? Is the education you’re giving your children so fragile? That’s how I would have replied to her.” And I thought he was absolutely right. I completely agreed with his reply. Naturally, a child’s education should not be such a shaky thing. What kind of education is it that gets shaken by a violent movie? I think that was how Mr. Fukasaku honestly felt. This may be overstating it a bit, but I think Mr. Fukasaku felt that way toward postwar Japan’s entire educational system.

I see things a little differently than Fukasaku and Kurosawa — and I wonder, perhaps, if Fukasaku’s films themselves don’t support a slightly different reading. Fukasaku’s reply seems to suggest the inability of one of his works to disrupt a solid, morally upright education. But, as I tend to think in terms of bad education, I would like to imagine the violence of Fukasaku as being a necessary part of one’s understanding of social life. This is not to suggest one should programmatically show children or young people violent films. However, it seems to me that Fukasaku’s work would disrupt an education, no matter how sturdy, and so much the better. Kenta Fukasaku, talking about his father, says, “what he hated most was that peace and righteousness have a tendency to put a lid on stinky, festering things.”

Fukasaku’s cinema, then, is indeed disruptive to any education that puts “a lid on stinky, festering things,” instead choosing to educate in such a way that exposes that which might be unpleasant or even harmful to an ideological education.

Best known for Battle Royale (2000) and Battles Without Honor and Humanity (1973), I find Graveyard of Honor (1975) and Yakuza Graveyard (1976) to be more exemplary of this impulse to pull the lid from the obscene. Those two most famous films of Fukasaku have the character of Jean-Pierre Melville, with heroic, principled characters at the center of disorienting, annihilating chaos. Fukasaku’s two films with Hakaba in the title are a little different. And although critic Mike White also traces the Melville influence from Le Cercle Rouge (1970) to the red circles of Graveyard of Honor, the twinned protagonists of Rikio Ishikawa and Kuroiwa Ryu are not men who function within the bounds of the hardboiled anti-hero. They are raw nerves, totally unequipped to apply any discernible principles to their conduct. Both played by Tetsuya Watari, this casting itself gestures toward putting an eye on that which is unpleasant. His role as Ishikawa was his first after a severe illness which prevented him from playing Bunta Sugawara’s role in Battles Without Honor and Humanity and got him fired from the NHK drama Katsu Kaishū (1974). As Graveyard of Honor entered production, his viability as a movie star was very much in question.

But he was a star playing Ishikawa, a seemingly apocryphal character in yakuza history. Most promotional sources and descriptions of Graveyard of Honor uncritically describe Rikio Ishikawa as a real person, though there does not appear to be much publicly available evidence corroborating what Fukasaku shows in the film. Goro Fujita, author of the source material, terms it a novel. He opts for fiction instead of memoir as “[t]oo many demands would be placed upon me” to write otherwise (Kaplan 4). Jasper Sharp similarly casts doubt on Ishikawa being real, calling him “an enigmatic figure … or perhaps figment” in his essay for Arrow Films’ Graveyard of Honor box set.

Both Fukasaku and Miike, tackling the Fujita novel, muddy the waters of the supposed historical facts behind Ishikawa. Fukasaku’s film begins with ostensible documentary photos and voice over, but the photos of an unidentified child who we’re to believe is Ishikawa quickly give way to black and white photos of Tetsuya Watari. The voiceover presented as someone who knew the real Ishikawa, delivering the line about a balloon floating upward that is one of the film’s major motifs, sounds like the voice of Tatsuo Umemiya, the actor who plays Ishikawa’s friend Kozaburo Imai. Miike does not opt for any of these documentary flourishes and instead makes things more self-evidently fictional, changing his main character’s name to Rikuo Ishimatsu (Goro Kishitani) and having a character named Yōko Imamura (Harumi Inoue) serving a similar function in the story to Imai. In fact, the only character that shares the same name across the two films is Chieko, played by Yumi Takigawa in Fukasaku’s version and Narimi Arimori in Miike’s.

As one would expect, Watari as Ishikawa and Kishitani as Ishimatsu give very similar portrayals. They both seem remarkable in their inability to foresee the consequences of their actions. Miike ratchets up the absurdity with a number of comedic slapstick moments for Ishimatsu.

Fukasaku’s version of Graveyard of Honor has a wild, circuitous plot involving a parliamentary election, postwar U.S. occupation forces, and conflict between the Japanese nationals and “third nationals” or daisan-kokujin. Miike trims things down, much more focused on Ishimatsu’s rise and fall in the Sawada family.

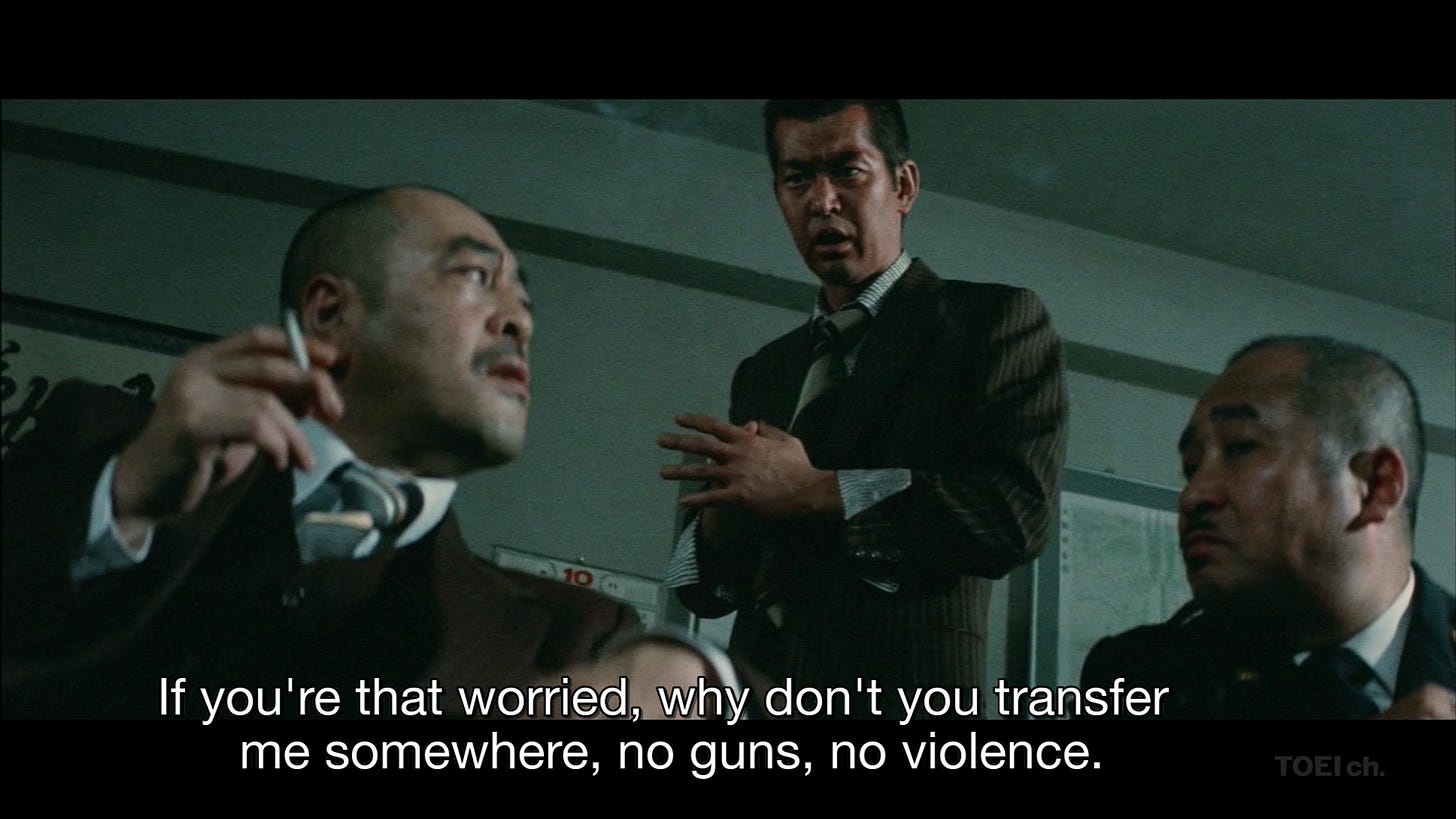

Though Yakuza Graveyard shares the grimy, unfiltered character of Graveyard of Honor, it is thematically quite distinct. Kuroiwa (when written with the characters 黒岩, literally ‘black rock’) is a police officer by trade rather than a yakuza and initially rejects them.

As similar as Watari looks in both roles, he shows tremendous range between them. Kuroiwa is not the hapless, perpetually confused Ishikawa. Although both characters are sensuous and pleasure seeking, Watari as Ishikawa always looks genuinely surprised when his self-destructive antics bring about the easily anticipated self-destruction. Kuroiwa is uncompromising and always prepared to meet the consequences of what he does. His name isn’t exactly subtle.

Fukasaku’s films in particular relentlessly point to the corrupt alliances among politicians, law enforcement, and yakuza. It’s the unpleasant but necessary underside of society that he attempts to reveal. In Miike’s adaptation of Fukasaku, he looks more deeply at the individual flaws of someone guaranteed to self-destruct. He rewrites the final near-death experience of the Graveyard of Honor protagonist before Ishikawa/Ishimatsu are incarcerated for the final time. In Fukasaku’s version, the narrator describes a bleeding, battered Ishikawa as, “a man seemingly destined to live … miraculously surviving by dint of his incredible life force.” The narration in Miike’s version describes Ishimatsu a little differently, “he didn’t die, though in spirit he had long been gone. His body simply refused to admit it.” Though one account seems more flattering than the other, if “incredible life force” is the same as a dead body that refuses to admit it houses a dead spirit, one might read the relentless hedonism and impulsivity as the mechanistic movement of a walking corpse.

The inability or unwillingness to control one’s impulses manifests in the tics of Fukasaku and Miike’s characters, most notably Kuroiwa’s nervous knuckle cracking. But these films show how this type of unrestrained figure is instrumentalized for the purpose of social cohesion. They are used by law enforcement, politicians, and even opportunistic yakuza bosses. Despite all the ceremony of yakuza life, these anarchic archetypes are discarded unceremoniously.

Tracksuits of the Yakuza

There are at least four notable tracksuits in Graveyard of Honor (2002). Masaru Narimura (Shinji Yamashita) wears the first one early in the film, but the next three belong to Yōko Imamura (Harumi Inoue), Rikuo Ishimatsu’s friend and foil. Imamura wears two of them, each while getting shot or stabbed by Ishimatsu. The fourth Ishimatsu steals while escaping from Imamura’s home. All four are eye catching. White, pronounced branding, some appear to have Looney Tunes-esque characters embroidered on them.

It means something that Takashi Miike decided to dress his characters in these outfits. They are the casual alternative to the signature yakuza suit. Even in a yakuza’s most intimate moments, however, they must be outfitted and uniformed. Visually, their white coloring contrasts with the blood that stains them. But I was more curious about what they are. As in, what brand? And how could it be that nobody had highlighted them and written about them in more detail? I’m here to correct this injustice.

I won’t bury the lede too much more, but there were a few details I keyed in on when trying to figure out what’s what. All of the tracksuits have “SMB New York” written on them and some of them have those cartoon characters.

These tracksuits are, unsurprisingly, from a brand called SMB New York. SMB stands for “Super Miracle Baby” and they’re designed by June Bergstrand. The cartoon character motif is pretty common on the garments I found.

I couldn’t find any concrete information about June Bergstrand or the brand itself online. The style is characteristic of the 90s and early 2000s. The embroidery evokes a sukajan style and the use of cartoon characters is similar to the American varsity jackets with actual (copyright infringing, I’m sure) Looney Tunes on them. Bergstrand spun off the brand into SB Jeans as a sub-label for denim. I had a pretty tough time finding any listings on Japanese resale sites like Yahoo Auctions and Mercari, but the listings were more plentiful on Grailed. I’m assuming you would be able to find some of this stuff at a Japanese 2nd Street or Treasure Factory, but I don’t remember ever seeing anything like this on my visits.

I’m sure there’s more to uncover, so I’m staying on the Miike tracksuit beat. If you know anything about SMB New York or have seen their gear in other Japanese movies from the late 90s and early 2000s, please drop me a line.

Weekly Reading List

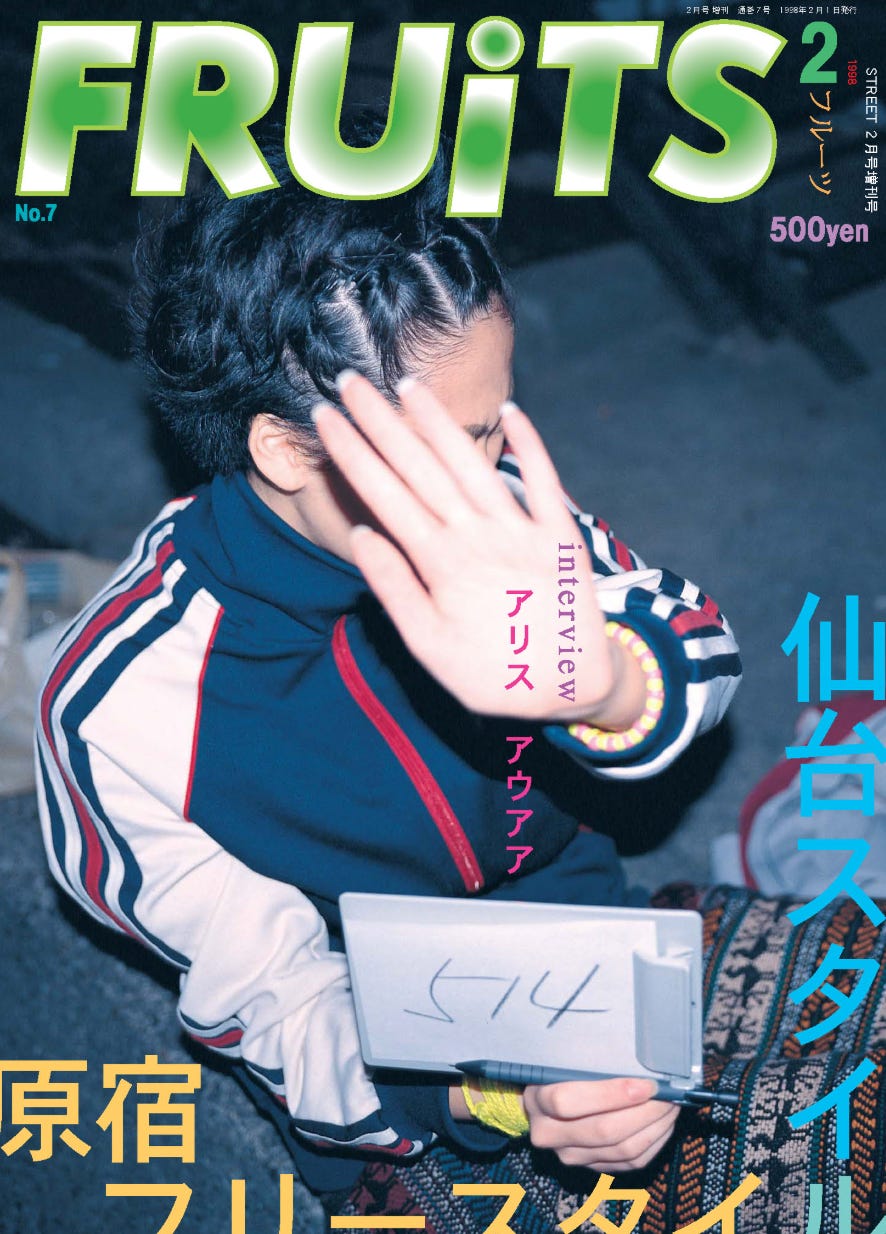

If you want, you can do what I did looking for info on SMB New York in old issues of Fruits:

Introducing the Paradox Newsletter Event Calendar

This week, I am launching what will be a weekly inclusion in the newsletter: an event calendar. It’s a document in service of that shared archive of cultural knowledge. For now, it’s almost entirely film screenings in the Boston area. I will add online events, nationwide movie premieres, whatever I think is relevant. You can use this to plan to see every single Mikio Naruse movie showing at the Harvard Film Archive.

Also, the Summer Games Done Quick marathon is on right now (if you are reading this within a week of publication). I have the end date listed on the calendar, but you can follow the link and tune in at your leisure.

Until next time.