Issue #391: The Staggering Genius of Kiyoshi Kurosawa's Cloud

There is manga. And then there is Hunter x Hunter (1998). I think self-contained narrative arcs are not the strong suit of individual shounen manga chapters. It’s not easy to have something that feels complete in thirty or so pages. And, if you’re a manga artist, you’re working toward a few different goals. You have to move the story along, you have to make stuff look cool, maybe narrative cohesiveness and thematic weight is not front of mind. Hunter x Hunter is so good because it does it all. Yoshihiro Togashi perfected conventional shounen manga with YuYu Hakusho (1990) and decided to reinvent the genre eight years later. There is so much creativity in the obstacles he sets up for his characters. But, for me picking up the manga for the first time after watching both TV anime adaptations, the feeling that you have actually read something worth thinking about with each chapter is so rare in the genre.

I wrote about Cloud (2024) this week. I’d been holding out to see it in theaters, and I’m glad I did. If not for Happyend (2025), it would easily be the best thing I’ve seen this year. It will have to settle for second best, but third is not close. The guns are so loud that they gave me a visceral flashback to another movie I couldn’t place in the moment. AJ reminded me: Heat (1995) has the loudest guns. And I saw both Cloud and Heat in the same exact seats of the Brattle Theater.

Cloud animates my mind much more than Superman (2025) or Fantastic Four: First Steps (2025) or 28 Years Later (2025) or Eddington (2025). Among those four, there really is only one worth watching: 28 Years. But I have essays on the back-burner about all four, though they may remain forever unfinished.

“Please keep focusing only on making money”: Financial Market Economy in Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cloud

One of my favorite podcast episodes, which I am sure I have mentioned before, is This Machine Kills’ November 16th, 2022 episode, “NOFTX.” As the title indicates, it was recorded on the occasion of the FTX collapse. In it, hosts Jathan Sadowski and Edward Ongweso Jr. make some reasonably bad predictions about cryptocurrency and offer very incisive analysis about what the cryptocurrency economy actually is. The episode’s show notes begin the lucid critique:

FTX is not an isolated event. FTX is not a bad apple. FXT is not uniquely mismanaged. FTX is not a cautionary tale. FTX is not a stunning surprise. FTX is a systemic problem, a vehicle for structural levels of fraud, another in a long line of liquidity crunches for crypto, a litmus test for credible due diligence, a fork in the road for the crypto economy, institutional investors, and government regulators.

In the episode itself, Sadowski says, “There’s no production anymore. It’s all financial engineering. And that’s all [FTX] was. It’s just price arbitrage.” The delta between the quality of the analysis and the accuracy of the predictions made by Sadowski and Ongweso is significant. About three years out from the episode, the crypto market is booming. FTX was a momentary blip. Bitcoin’s market capitalization, meaning the total market value of all bitcoin “in circulation,” has grown from $313,012,826,679 in November 2022 to $2,294,030,797,008 at some point in the evening of August 4th 2025. In plain English, that’s a jump from 300 billion to 2 trillion in two and a half years.

In deference to Sadowski, Ongweso, and common sense, there is another crucial point here: there is no bitcoin literally in circulation because bitcoin does not circulate in a consumer economy in the same way as money, commodities, or other types of capital. Its value is completely illusory, and what its market cap means in fact is determined by a pricing abstraction. It is the “value” if everyone sold their bitcoin holdings at its current price. If everyone sold their bitcoin at the same time, the price would drop precipitously.

But this is true for any commodity or stock. Market cap is not meant to indicate what 100% of the owners of a commodity or cryptocurrency or stock could expect as a return at every given moment if they all sought that return at the same time. And the reason why Sadowski and Ongweso’s predictions about crypto will not come to pass is because they don’t take their indictment far enough. Every systemic issue they point to in crypto is not unique to it. Their critiques of cryptocurrency trading are critiques that apply equally to the entire stock market apparatus. Any “trading” of commodities, stocks, or other financial instruments entails an exchange where the “value” is illusory and reliant on a naive, but enduring, social contract. To take the critiques they make seriously, and administer them as widely as they are applicable, would be to pull the loose thread of the financial market economy until it is utterly disassembled.

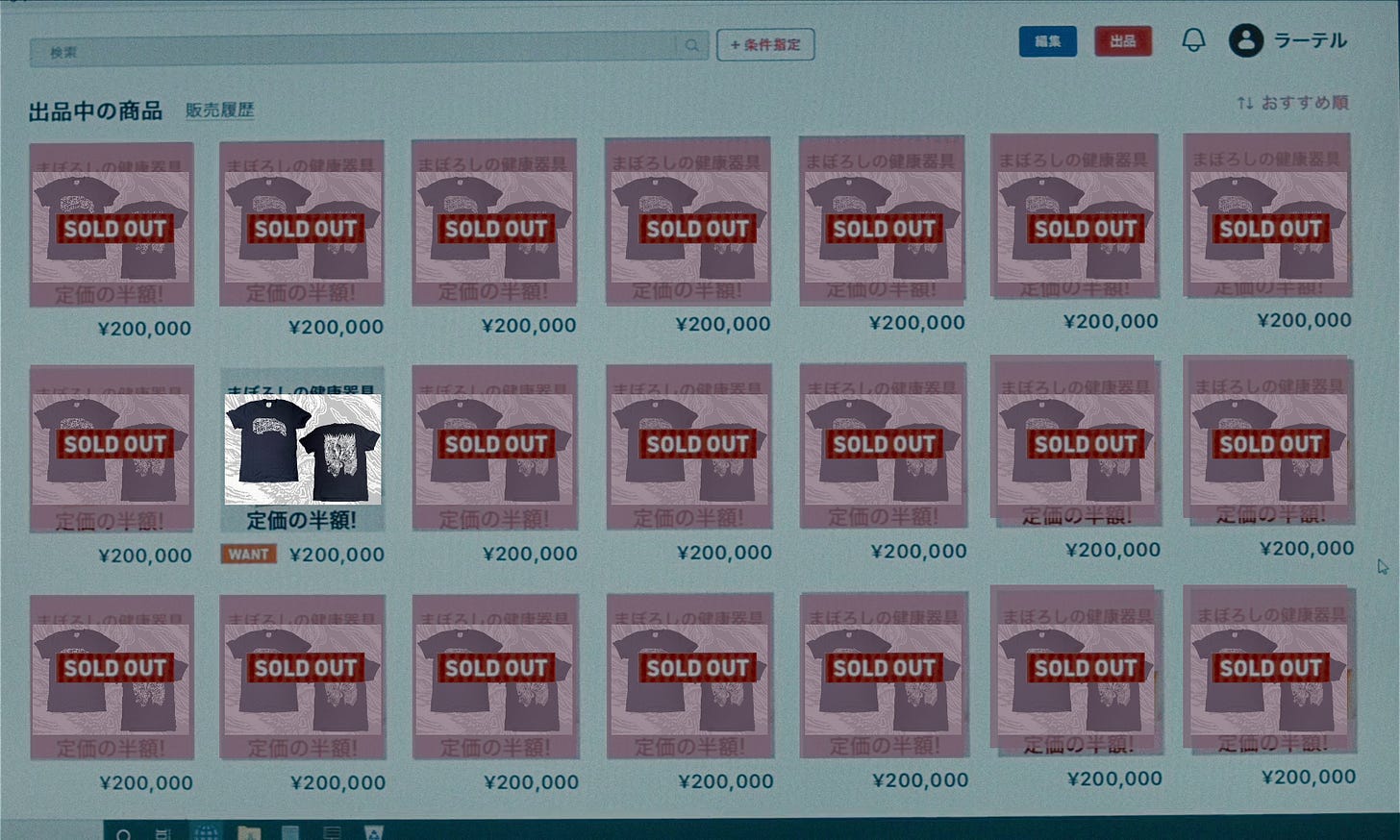

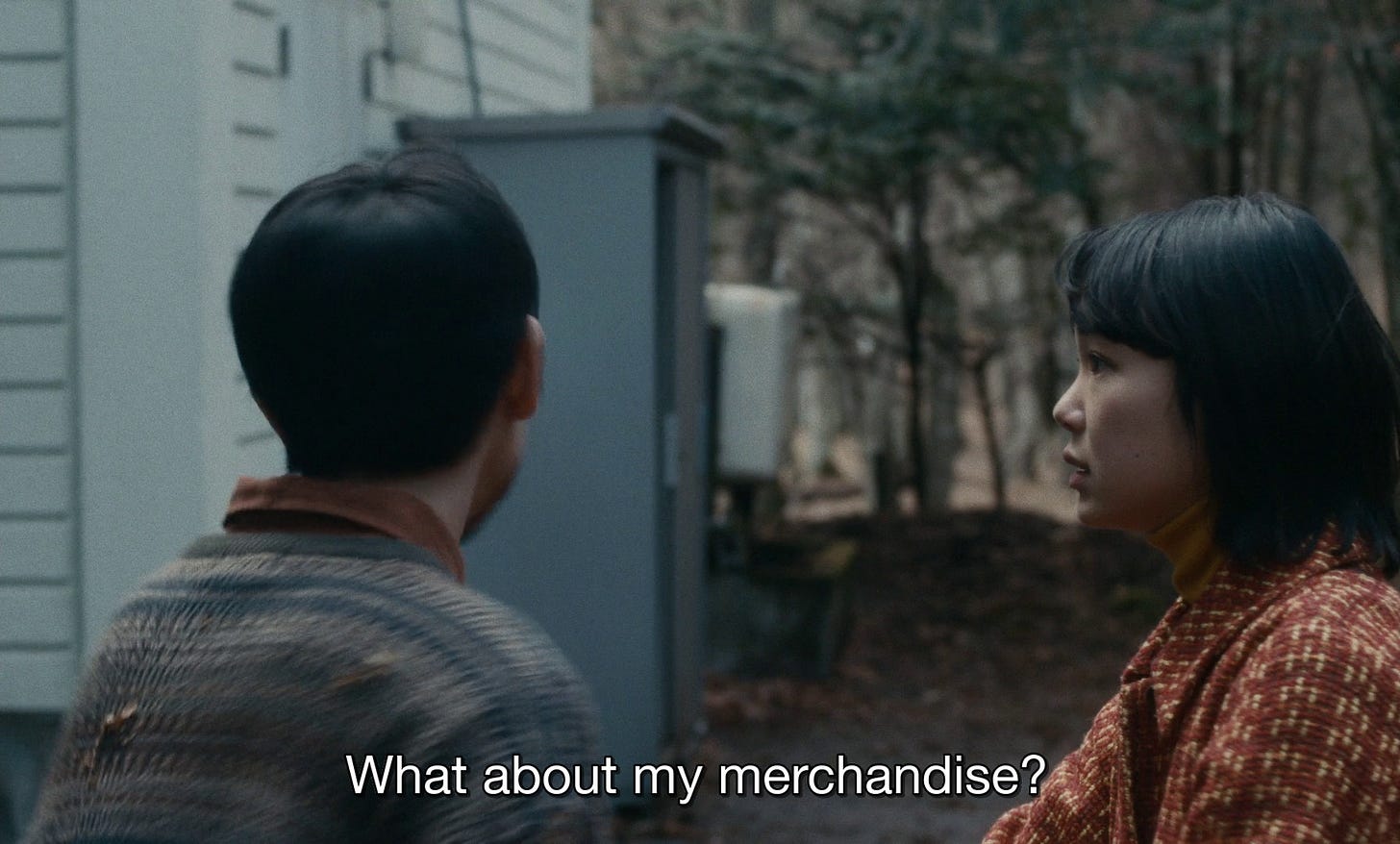

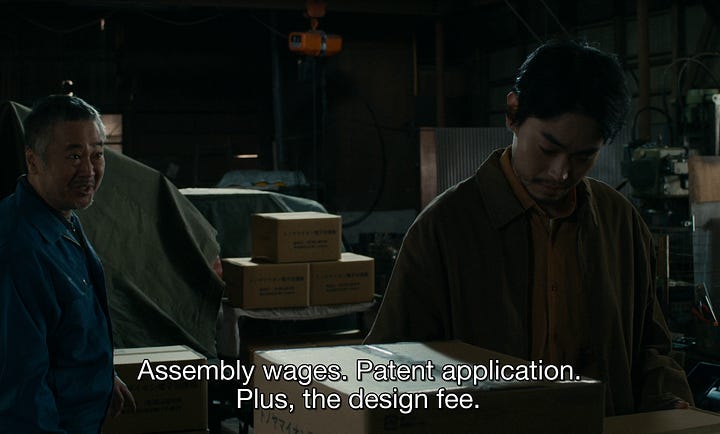

Kiyoshi Kurosawa has no such reservations about disassembling the financial market economy in his latest film, Cloud (2024). His protagonist, Ryosuke Yoshii (Masaki Suda) abandons his job at a garment factory in favor of online reselling. This is an economic parable about the movement away from concrete, material foundation for economic value to an abstract, arbitrary version of supply and demand where supply is artificially constrained and demand is artificially inflated. Yoshii’s work as a reseller distorts the labor theory of value, rendering incoherent the relationship between labor and commodity price. Yoshii labors, but this does not define the value of the product he sells. The film works this idea to the bone. Yoshii begins the film buying medical devices from a factory owner, Tonoyama Souichi (Masaaki Akahori). As Souichi outlines the various costs, prices for labor, associated with the production of the device, Yoshii ignores those economic drivers and instead suggests Souichi may need to pay for the disposal of the devices as junk.

There is a clear thesis here: value doesn’t come from any manifest quality of a commodity, but rather how much profit one can generate based on whatever mechanism. Because Yoshii hasn’t yet caused the scarcity he will exploit in his selling, the market conditions he makes the purchase in are such that there is a surplus of thirty medical devices Souichi seeks to offload.

Though Yoshii buys and sells physical commodities, Kurosawa’s economic analysis here does not just apply to counterfeit handbags, video games, GPUs, or even concert tickets. This is an indictment of the economy as a whole, and particularly the crypto and financial market economies where value is more obviously a collective hallucination rather than a product of human labor.

“When we started out, it was because we wanted to make easy money. Is life easy now?”

Despite Kurosawa’s wide-angled economic critique in Cloud, he treats his characters with remarkable compassion. Yoshii retreats from the productive economy to unproductive economic alchemization because of an existential misalignment between himself and the world at large. Kurosawa chose reselling as the subject matter for the film because of a friend who “isn’t really suited for a corporate job,” and thus has become a career reseller. Yoshii is not a unique bad actor, but merely functioning in an economy that is distorted enough to sustain his practices of arbitrage, rent-seeking, and scalping.

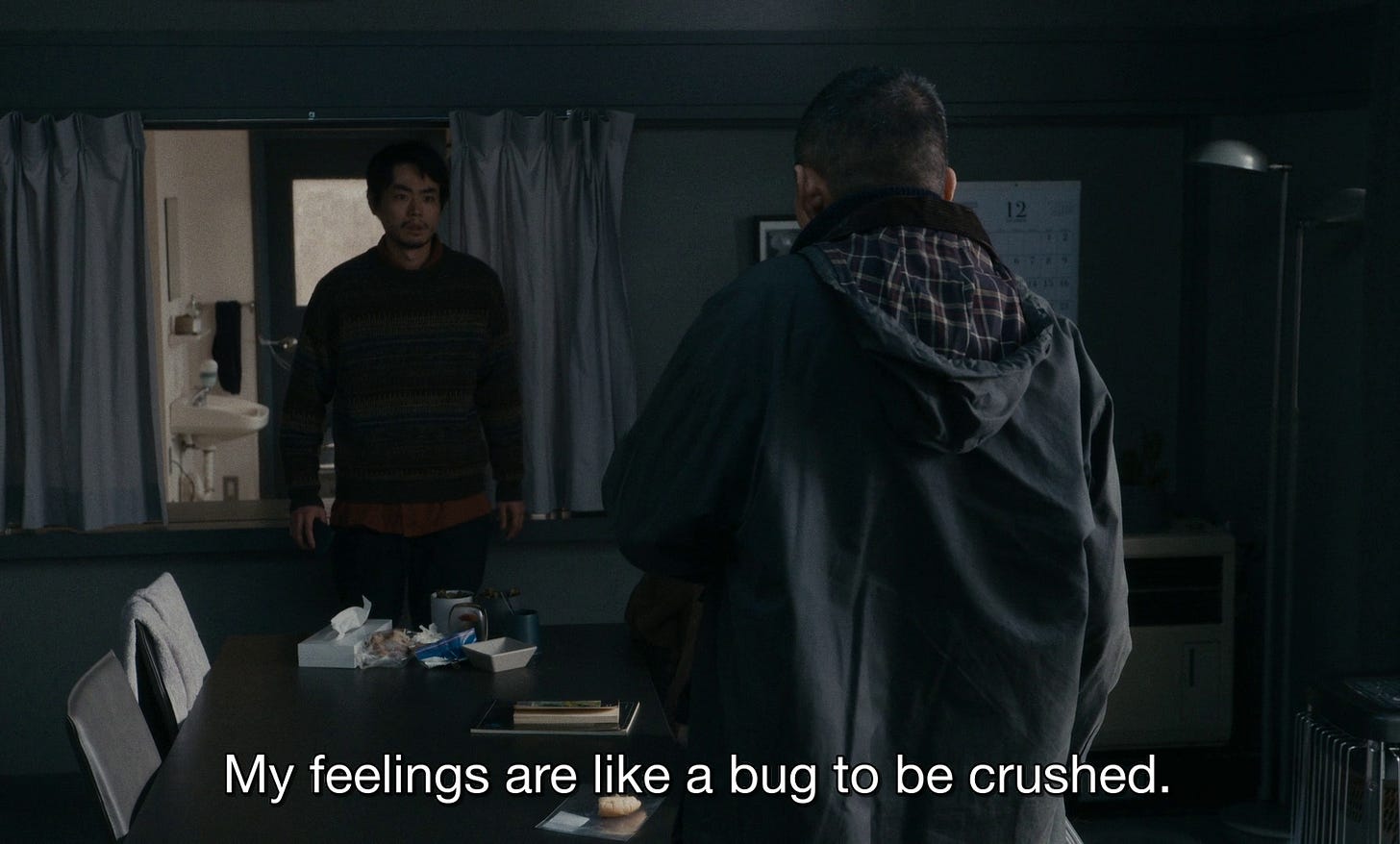

This inhuman economy puts Yoshii in an unenviable position relative to the other people he meets. His girlfriend, Akiko (Kotone Furukawa) plays out a domestic drama that is inescapable because of the financial incentives. Kurosawa also deploys a uniquely modern nightmarish premise where everyone who believes Yoshii has wronged them joins forces to torture and kill him. This includes the medical device factory owner Souichi, as well as Yoshii’s old factory boss, Takimoto (Yoshiyoshi Arakawa), a man who bought fraudulent goods from Yoshii to resell himself, Miyake (Amane Okayama), and Yoshii’s reselling oldhead, Muraoka (Masataka Kubota).

The escalation within this aggrieved league comes from the internet. Kurosawa says in his interview for the Film at Lincoln Center Podcast:

It’s as if we have forgotten about the mysteries of the internet, and that has made it more dangerous. For instance, even small things that we are feeling within us can become enlarged and heightened over the internet. All these kinds of emotions can also be collected and concentrated to make something very big.

This is Kurosawa’s revision of the themes he explores earlier in his career, such as in Pulse (2001). As the group eggs each other on to greater extremes, there is a clear parallel to the eruption of ridicule toward, abuse of, or attempts to materially harm someone who becomes the object of collective online ire.

“I’ll sell them all before I find out”

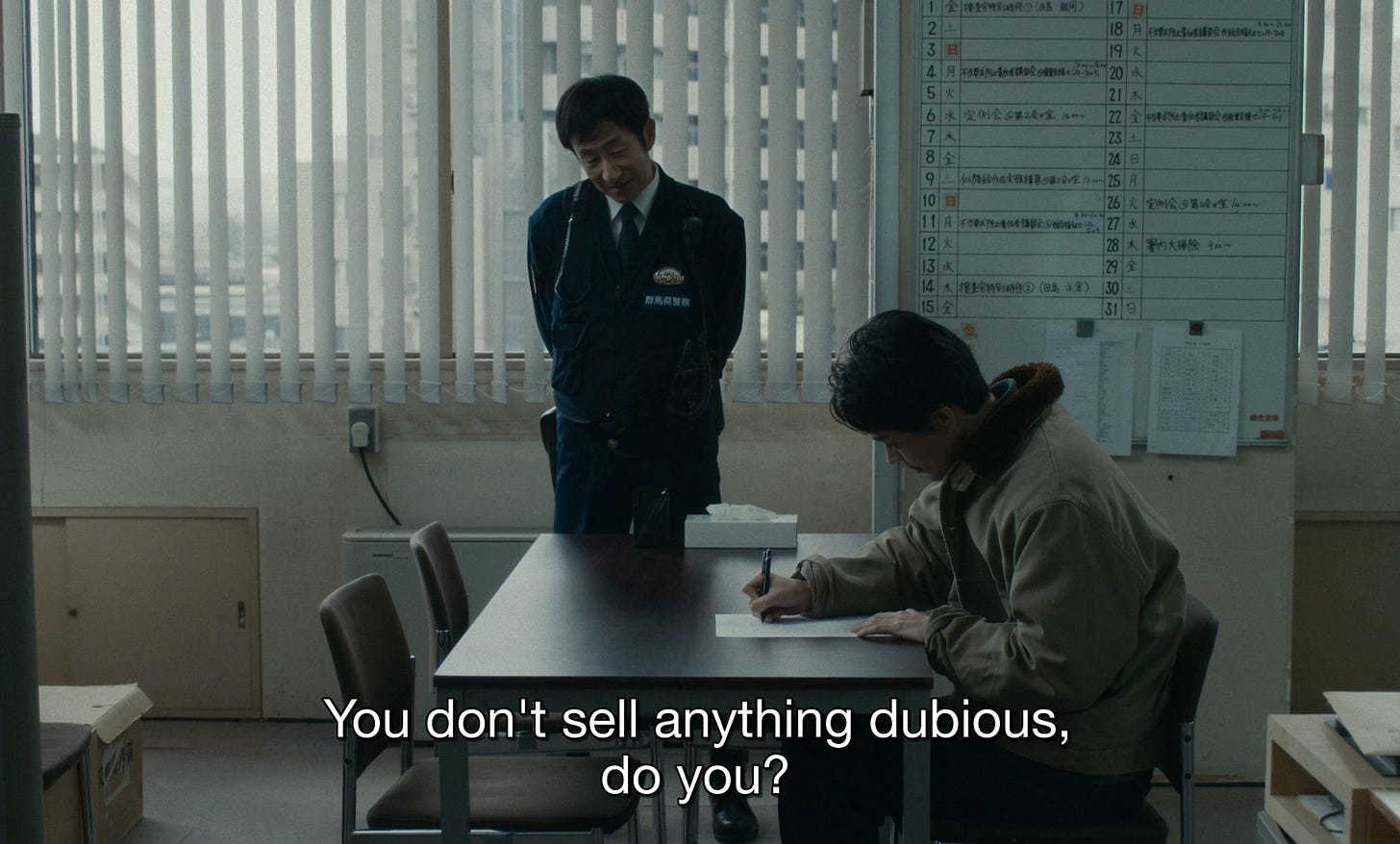

If any of Yoshii’s assailants have a legitimate grievance against him, it is a result of how he operates as an economic actor. The opening scene also makes this clear. Chizuru (Maho Yamada), Souichi’s wife, asks Yoshii, “How will you price these therapy devices?” to which he replies, “I don’t know. Depends on the market.” Yoshii can justify his lowballing through ignorance. He deliberately does not know about the markets in which he will enter, attempting to make his profit-seeking more moral. This, of course, has the opposite effect. Chizuru asks him:

You operate on impulse and instinct? No effort whatsoever? Even though that’s wrong somehow?

The lack of effort in research to understand appropriate prices for which one can buy and sell a commodity is the evacuation of labor from the value he fantasmatically generates — simply by entering a number in a text box.

He pleads ignorance in the same way with respect to a haul of handbags. He asks his assistant, Sano (Daiken Okudaira) about the bags, his unassuming question: “do you know what this is?” Sano goes from saying they’re real to saying they’re fake, and Yoshii claims he doesn’t know, “I saw a photo. 10,000 yen each. I’ll sell ‘em for 100,000.” Sano asks him, “being real or fake doesn’t matter?” to which Yoshii responds, “it doesn’t. I’ll sell them all before I find out.”

Using intuition and instinct puts reselling in the realm of gambling, another important association for Kurosawa. Ultimately, though, Yoshii knows the bags are fake despite his self-deceptive assertion. When confronted by the police about the possibility of possessing “fake designer goods,” Yoshii claims to have sold them all and quickly reduces the price so he can ship them as quickly as possible rather than turn a sample over to the police for inspection. Yoshii implicitly deceives his customers by way of an explicit deception of himself. These layers of subterfuge are what, according to the film, sustain every dimension of the modern economy.

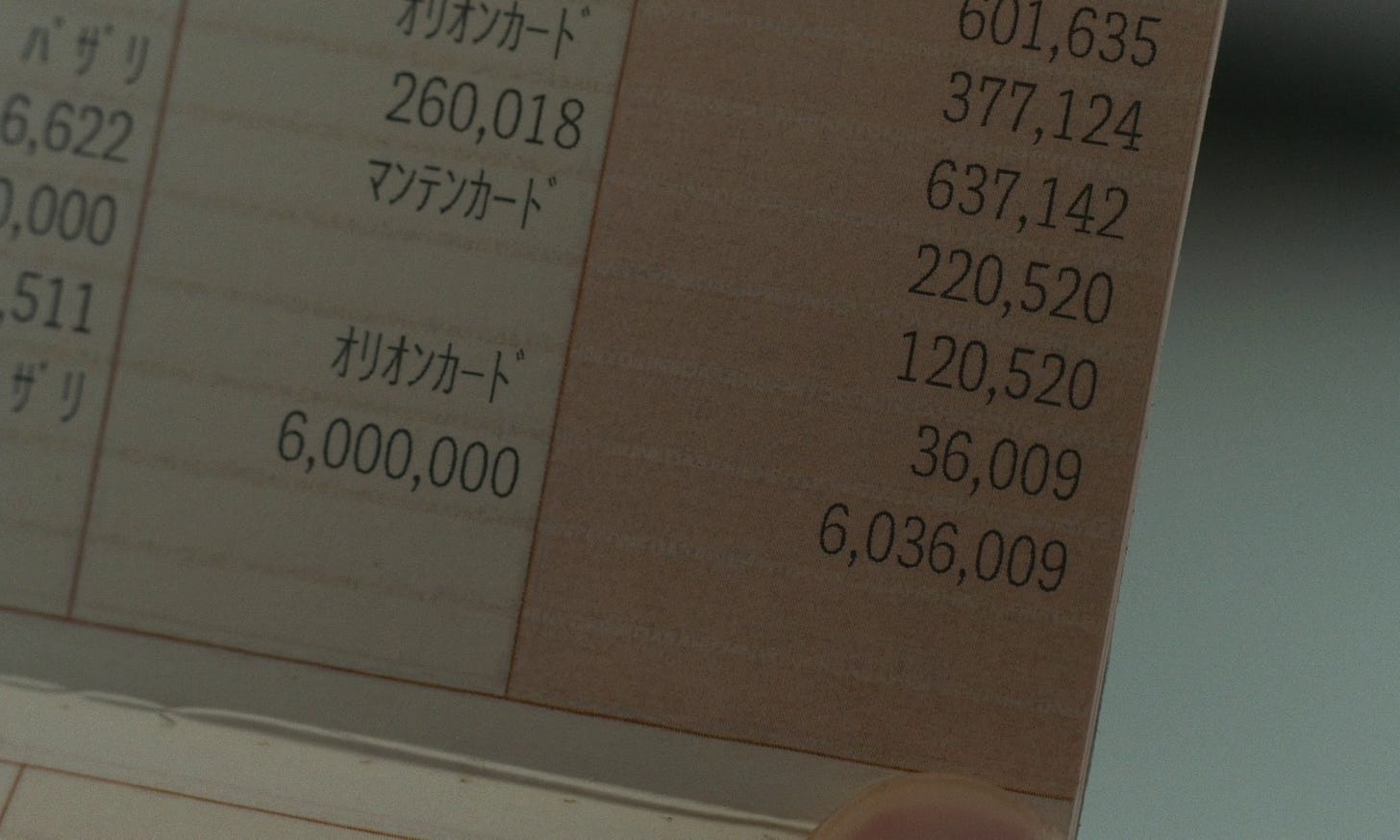

“Your credit cards? You know they’re all I want”

Economic strictures also govern intimate, domestic relationships, such as the one between Yoshii and Akiko. Akiko is neglected, as Yoshii only seems to have eyes for his merchandise.

However, Yoshii seems eager to occupy the position of the breadwinning husband and grant Akiko the role of credit card swiping, kitchen occupying wife.

On the other hand, Akiko relishes one of those matrimonial duties more than another. She has no aptitude for cooking or housekeeping, but is eager to spend money.

Like Yoshii, she is ill-suited to the conventional domestic life to which Yoshii seeks to cosign them both. Whether by will or skill, she cannot perform the labor that should grant her the unwritten right to spend their shared money. She is just like Yoshii in her rent-seeking aspiration to extract value from an economic system with minimal labor.

Despite the way Akiko fits into certain misogynistic stereotypes, Yoshii’s choice of vocation is structurally identical to the supposedly “feminine” position of simply asking to use a credit card.

Akiko and Yoshii’s relationship is also a continued interrogation of sexual difference and gender antagonism. Akiko’s position parallels that of Fumie (Anna Nakagawa), Kenichi Takabe’s (Kōji Yakusho) wife in Kurosawa’s Cure (1997). Fumie’s schizophrenia results in repeated botched or bungled attempts at fulfilling her domestic duties. Because of the rigid gendered subject positions Takabe and Fumie occupy, neither can behave in a way best suited to enrich the other. Fumie continues to act out these duties for Takabe’s benefit, resulting in Takabe having to come behind her and, for instance, turn off the clothes dryer. Takabe is locked into his obsessive murder investigation, unable to give Fumie the care that she needs and sufficiently impress upon her that she should not do that which she can’t.

Fumie and Akiko’s domestic foibles are distorted mirrors of the other, even as the causes are far different. Takabe and Yoshii are both drawn into a violent spiral because of the way their vocations ensnare them.

“I’ll be your support”

Yoshii’s path to hell is guided by Sano, a young man hired by Yoshii as an assistant. Kurosawa is clear about Sano’s narrative function:

His role in the narrative and his role in this movie is very clear. He is the devil. He is someone who, in exchange for granting people’s wishes or their desires, takes a bit of their soul.

He is analogous to Cure’s Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara), the architect of the protagonist’s violent downfall or, perhaps, ascendancy.

Sano’s similarities to Mamiya are more than surface level, but they begin with their discourse. Sano acts in bizarre ways with ambiguous motivation. Even though he seeks to explain himself saying things like, “It’s my choice,” and “I’m your assistant,” these syntactically meaningful phrases do not actually have any meaning with respect to why Sano does what he does.

The complicated nexus of textuality in Cure has many such examples, all from or because of Mamiya. Mamiya is incapable of giving an account of himself. He turns language in on itself, occasioning frustrating circular exchanges between himself and Takabe. The spaces into which Takabe and Yoshii enter evacuate coherent speech of substantive meaning. This is a dismantling that resembles the economic movement of Yoshii from factory worker to reseller. The inability to find the defining standard that serves to make sense of speech or economic value is the perennial problem Kurosawa explores.

“I didn’t know you’d found conventional happiness”

Though Cloud has many surreal and allegorical elements, the activities that a career reseller would engage in are represented with sociological precision. Specifically for sneakers, resellers line up to buy out a store or even pay their friends a share of their anticipated profits to get their hands on sought after stock before release.

Kurosawa is attentive to these realistic details, juxtaposing realism with genre in his making of the film. In his Lincoln Center interview, he says:

I just simply love genres films. In fact, I think of genre films as the epitome of filmmaking, something that starts from the real, but then approaches a world that can only be built through filmmaking.

At the same time, he discusses the tension between the realism he feels is necessary for his films and the fantastic quality genre imposes through its formal conventions. He discusses the way Cloud might be misread as a comedy because of this tension:

I wanted to depict people that might actually exist in reality that end up in a situation like a gunfight. If that were to happen in reality, there’s no way they could shoot a gun while looking very cool. It’s their first time and so they’d be filled with that kind of hesitation and as a result it makes sense that they might look foolish or comedic. But it is that I was trying to depict a kind of realistic idea of regular people ending up in this kind of situation.

He is fastidious about these realistic elements, down to wardrobe, outfitting his cast in a range of illustrative footwear reflective of the character’s age and disposition. One of the men hunting Yoshii wears distinctive Puma Thunders, compared to boots and monochromatic athletic sneakers.

As important as commodities are both to the characters and to the film’s sense of realism, Kurosawa insists on their illusory value and tenuous social meaning. He ends his film with one of the great, and comparatively understated, shots of financial ruin in the tradition of The Killing (1956) and Any Number Can Win (1963). As Akiko falls to her death after trying to kill Yoshii, he drops the credit cards she is willing to kill for.

Kurosawa’s critique of the modern economy and financial markets is relentless in Cloud. But the density and richness of the film comes at no cost to his meticulous craftsmanship.

Weekly Reading List

Pretty good list, what you would hope to see from Kurosawa.

https://www.lacanonline.com/2025/07/news-july-2025/ — Hewitson’s July news update for LacanOnline is full of heaters.

Event Calendar: Woo and Lam

Added to the event calendar this week: HK action as part of the Coolidge After Midnite series. They’ll run six movies through September, five by John Woo and one by Ringo Lam. Friday and Saturday night midnight movies, back to back, are tough. I might have to pick my spots here. But they’ve got a hell of a lineup.

Until next time.