Issue #413: Stranger Things and Speedrunning

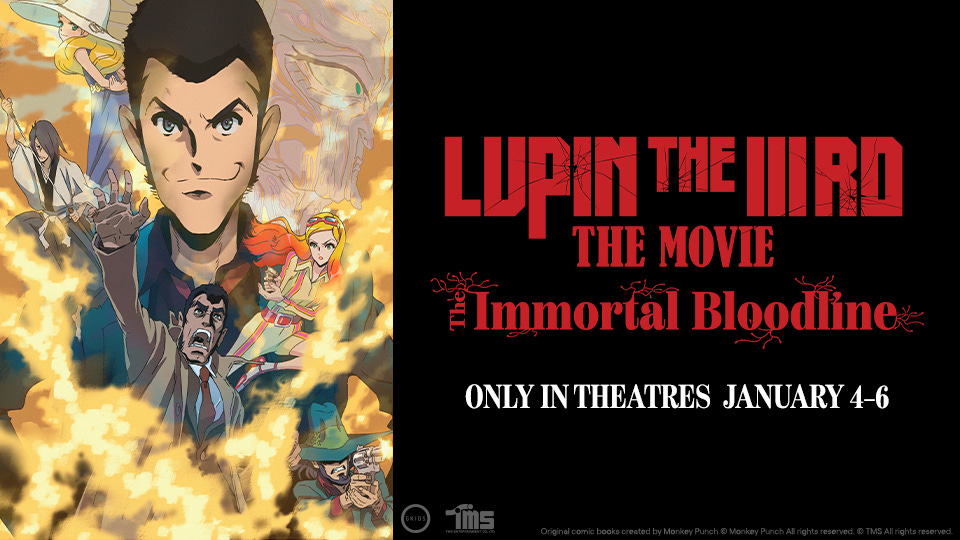

I’m going to the movies today.

The latest installment in Takeshi Koike’s critically acclaimed interpretation of Lupin the IIIrd is screening in U.S. theaters. I have only seen a few episodes of The Woman Called Fujiko Mine (2012), the beginning of Koike’s stewardship of the characters. But I have to seize my chance to see Lupin in theaters. Maybe this will inspire me to open my other three Blu-Rays of Koike-directed Lupin feature films.

In other news, the recent Music League category about influential artists was my favorite by far. This is the best Music League playlist of all time from any of our seasons.

I should’ve assumed this playlist would be good, but I had a pretty tough time figuring out what to submit. I was a little to attached to the idea of thinking about what influences my favorite artists (the round title: “My Favorite’s Favorite). My favorite artists are usually the ones who do the influencing. But I ended up choosing Discharge on the basis of their influence of Disclose. They’re both bands I love. In my description, I understated the relationship. Disclose adopted their visual language, song structure, lyrical content, everything from Discharge. But Disclose delivers on the promise of Discharge in a way as the more consistent band. Tragedy (1994), The Aspects of War (1997), Nightmare Or Reality (1999), and Yesterday’s Fairytale, Tomorrow’s Nightmare (2004) are all timers.

When it comes to Discharge’s influence, though, it’s incomparable. I wrote in my submission:

Within extreme music, there are few more influential bands. Discharge is probably competing only with Motörhead, Black Sabbath, The Ramones, and Venom. The enormous shadow they cast is a gift to music. For my listening habits, they are a strong influence on the largest number of bands I like and listen to regularly and it is not close.

I came in fourth in the round, which was a surprise since the group is not always hospitable to extreme music. I wasn’t the only one who did well submitting hc, Scot came in third with The Stalin. The playlist also treats us to the smooth sounds of Robert Johnson, Celtic Frost, Suede, Die Kreuzen, and Soulja Boy.

Speedrunning Gazette: AGDQ 2025

The GDQ speedrunning marathons are a common topic for my newsletter. If you’re not familiar, you can read some of my previous writing about them:

Or read about the marathon from the horse’s mouth:

https://crowd.gamesdonequick.com/

We’re only two days in to the marathon, but there have already been plenty of interesting moments.

6 7 Gestopo Comes for GDQ

Erin and I made a bet on the number of times someone would make a “6 7” joke at GDQ. The first opportunity was early, during the opening run of Super Mario Sunshine (2002). At about an hour and ten minutes into the run, commentator JJsrl starts explaining the nuances of the “6 tooth” and “7 tooth” strategy.

Another commentator, rosa_lul says after the explanation, “I feel like a sleeper agent trying not to activate hearing those two numbers together.” I haven’t watched every minute, but is GDQ staff discouraging its runners and commentators from making 6 7 jokes? Is 6 7 dead? Time will tell.

Learned Parapraxis in Speedrunning

GDQ does not always spotlight the best runner. Play skill is important, but even more important for the marathon setting is being presentable, conversant with the audience, and entertaining. The Jet Set Radio (2000) run was a welcome exception with world record holder DylCat at the helm.

DylCat demonstrated the “optimal” method of tagging in the game:

He says, “I’m basically just tensing up my arm and pressing X. It’s not good for you, you should not do this regularly, but it’s optimal … so I do that for a lot of the run.” This is demonstrative of the sporting mentality that comes with something like speedrunning, which is analogous to the competition of “esports.” Jack Black writes in “Revisiting the sport ethic” (2025), “valorising dedication, sacrifice, and the prioritization of athletic achievement, above all other considerations, the sport ethic describes a widely accepted expectation that athletes will internalize and enact a set of required values in pursuit of sporting excellence” (1-2). DylCat’s commitment to this “sport ethic” is evident in his advise to the crowd, to not emulate his self-harming controller technique. There’s an obvious contradiction here, however. DylCat is the greatest Jet Set Radio speedrunner. To compete with him, one most likely must use the control technique he advises against and indicates is harmful.

This tension supports Black’s greater psychoanalytic insight in his piece. He writes, “the enduring power of the sport ethic does not lie entirely in institutional reinforcement or cultural tradition, but in the unsettling possibility that we—both athletes and fans—enjoy it” (5). Black goes on:

[T]he sport ethic operates not merely as a behavioural code, but as a moral telos, inasmuch as it remains a vision of the good that is tied to ideas of authenticity of self-worth.

Yet, this ‘good’ is not only pursued by athletes, but, at the same time, sacrificed, insofar as many of the goods commonly associated with sport, such as physical and mental wellbeing, ethical conduct, and inclusivity, are actively transgressed in maintaining and adhering to the sport ethic. As a consequence, what is sacrificed in the pursuit of the sport ethic is the very idea of sport as a space for health, mutual respect, and human flourishing. While fostering the normalisation of injury, the erosion of moral boundaries (e.g. through doping or cheating), and the exclusion of those unwilling or unable to conform to the sport ethic, alongside commercial logics and institutional demands that exploit athletes’ labour under the guise of commitment and professionalism, ultimately, what is surrendered is the ‘good’ of sport as well as its capacity to offer meaningful experiences beyond instrumental success.

GDQ marathons and speedrunning as a whole reflect this claim by Black in a number of ways, including the very obvious strain of a 24/7 televised event that invites participants and viewers to forego sleep contrasted with the charitable cause GDQ enriches with its significant financial contribution. But it’s DylCat in particular who exposes the more urgent harms one visits upon themselves through their “overconforming” to the sport ethic in the pursuit of speedrunning achievement. DylCat’s example of a harmful controller grip also belongs on a list of examples that support Ryan Engley’s argument in his presentation at the Lack V conference in 2025 where he claims the movements characteristic of sports are “learned parapraxis,” deviations from a norm that can result in significant bodily harm to the athlete.

Because of DylCat’s sacrifice, we’re treated to a marvel.

When Making a Game Easier Actually Makes it Harder

During the run for Shovel Knight: King of Cards (2019), commetator spikevegeta makes a case for the category, “NG+,” being as hard or harder than other categories. “NG+” is short for New Game +, describing a mode of play available in many types of games where one begins the game over again with all of the upgrades, power-ups, and other accumulated game assets that benefit the player.

In a normal case, this certainly means the game will be easier. However, because of the different goals of speedrunning, runs in a “NG+” category may be harder — as spikevegeta suggests is the case for King of Cards. Because of the greater capacity for movement the power-ups provide, the runner must achieve more executionally complex feats of dexterity. With more gameplay choices for traversing an environment, there is a greater planning challenge to determine the optimal approach to an area of the game. For me, this is a thought provoking game design idea. Affording the player with more tools and more choice can make a game more difficult with the goal of speedrunning, “beating the game in the shortest span of time.”

Speedrunners Embracing Randomness

Along those lines, the Final Fantasy X (2001) speedrun category presents a similar point of philosophical and design inquiry for beating games quickly. Because Final Fantasy X utilizes RNG (random number generator) seeds, every outcome in the game that seems random is deterministic based on the unknown quality of the seed. Over time, players have been able to identify the various seeds and thus predict perfectly various outcomes based on the actions the player takes. To speedrun a game with this kind of RNG system would mean constant resetting to find the optimal seed. This is not a good experience for a player or a theoretical viewer.

As a solution, the Final Fantasy X speedrunners have embraced a “true RNG” mod which eliminates the RNG seeds and makes the various ostensibly random game events, number rolls, and so forth truly random. This eliminates the incentive to reset for the appropriate seed or the requirement to optimize one’s play for a specific seed and instead creates a more dynamic speedrunning environment. While most speedruns endeavor to minimize randomness by “RNG manipulation,” the cost to the experience for the viewer and player is too high for FFX.

There is a quality of randomness to the possibility to make this choice, as many speedrunners are forced to optimize for specific seeds in games where no community developed “true RNG” alternative exists. Indeed, it just so happens that someone decided to make this mod and thus open up this choice between RNG and seeded gameplay to FFX runners.

The Secrets of the World Are Not Hiding in Netflix’s Regulatory Filings

Stranger Things (2016) is over. It took nearly a decade to get to the conclusion of its five seasons. It doesn’t sound too outrageous to me to take, on average, two years to produce a season. But I can understand the frustration of the fans with the growing wait between each. Season two came out in 2017, a little over a year after the first. Then, season three in 2019. Sure, we’re on track. Season four? 2022. Okay, well there was COVID and other apocalyptic threats.

The wait for season five must have been the most frustrating of all. Three years removed from the “Running Up That Hill” moment from Stranger Things season four where the song was used incessantly, the final season arrives.

Fortunately for me, I am not a Stranger Things fan. I watched season one back in 2016 and felt no inclination to watch anything that has come after. But the advertising and conversation steered me back to Stranger Things in December. Nothing I’ve seen has made me a fan, but I am up to the third episode of season five and planning on watching through til the end.

I don’t think Stranger Things is a good show. When I have said this to people I know in the last month, they have responded with things like “well, it’s a show for children.” I watch shows for children, like Kamen Rider. This isn’t that. The enormous adolescent fandom Stranger Things has accumulated seems incidental, reflective primarily of the fact that its principal characters are adolescents. Instead of being for children, it appeals more to the, benevolently, young at heart. It delivers 1980s nostalgia relentlessly. It’s one of the show’s strengths — fantastic production design. If the target audience for Stranger Things is those who remember growing up in the 1980s, I’m too young. But there are still parts of the childhood Stranger Things depicts that feel resonant and familiar.

In the season two episode “MADMAX,” where the Stranger Gang (made this term up) goes to the arcade, I feel like I am there. In season three, which turns the primary setting from a small town to a expansive mall, I remember the hours I spent in my own local malls as a kid. Season two is the show’s high point, but season three has its bright spots. In the finale, “The Battle of Starcourt,” the Duffer Brothers manage to capture the anguish of moving as a young adult. I take geographical distance for granted today, but I remember that horrendous sense of finality that came with a friend’s move when I was young. There are friends I had in middle school who moved away that I’ve never reconnected with. As the Byers family and Eleven (Millie Bobby Brown) pack their bags to move to California, the Duffers linger at the right spots with forlorn looks around empty rooms and friends dragging their feet as they move boxes they would rather stay put. The show deserves a lot of credit for its highs, capturing youthful struggles with the subjective weight for the young person instead of the retrospective adult view. They even manage this to some degree in their depiction of bullying in season four.

Season three is also the beginning of some deleterious narrative problems the show never fixes. The lived in feeling and vivid geography of Hawkins evident in season two is gone with season three’s focus on the mall. Even worse, the show employs the storytelling technique of separating its characters in a way that diminishes the possibility of storytelling flexibility and deprives the cast opportunities to play off one another. The “party” that navigated seasons one and two is rarely together in the subsequent seasons, whether because of scheduling conflicts or the Duffers running out of ideas.

From season three onward, the show groups Dustin Henderson (Gaten Matarazzo), Steve Harrington (Joe Keery), and Robin Buckley (Maya Hawke) on a parallel track to Mike Wheeler (Finn Wolfhard) and Eleven, and on yet another track there’s Jim Hopper (David Harbour) and Joyce Byers (Winona Ryder). One of the more compelling and surprising relationships of the show is that of Eleven with her adopted father Jim, but this relationship is woefully underdeveloped after season two. Max Mayfield (Sadie Sink) and Lucas Sinclair (Caleb McLaughlin) generally have something to do in the show, but the biggest casualty of this storytelling structure is Will Byers (Noah Schnapp). After his absence in the first season, the Duffers can’t quite figure out who or what he is supposed to be to the rest of the cast.

The discrete and seemingly intractable character groupings which persist on some level even through the fifth season is an excellent case study for a narrative failing of much prestige-aspiring streaming drama. Expanding the normal A/B plot structure of a television episode to arbitrarily follow three, four, or five groups of characters during its runtime makes thematically cohesive and narratively satisfying episodes impossible. To make matters worse, this narrative structure in the last three seasons compares so unfavorably to the first two which created the opportunity to bring characters together in unexpected ways and sustain a broader plot instead of having to move the many separate plots to some point of connection. The conclusion of season four almost seems satirical, as the Duffers contort their plot for a contrived climax that involves Eleven, Max, and Jim working together from California, Hawkins, and Russia respectively.

So far, season five doesn’t seem much different from the two seasons that preceded it. The setting has once again transformed, this time to a dystopian Hawkins under military quarantine. This seems like an overcorrection from season four which introduces the U.S. military as an antagonist who don’t have much impact on the plot. Season four connects the show’s antagonist, Vecna, to Eleven’s past in a way that probably wasn’t planned but has enough incidental foreshadowing to feel planned — probably the cause of all the attributions of meticulous plotting to the Duffers.

Despite my thinking that season five is delivering at more or less the quality level I would’ve expected, some people hate season five. This hatred is evinced by widespread conspiratorial thinking around Stranger Things. A barely coherent Change.org petition demands the release of “unseen footage” to the tune of nearly 400,000 signatures. The confusingly named “#conformitygate” conspiracy suggests there is yet more Stranger Things to come, with the real season five release impending to supplant or supplement this promotional release. One struggles to comprehend the logic behind a promotional methodology that intentionally releases hours of narrative television to be panned and later supplemented so it all makes sense.

My impression of Stranger Things after my fast paced viewing is that the show makes more or less as much sense as it ever did. I would never present the show as an exemplar of internal consistency or detailed explanations, which I think is a good thing. The Duffers, in fact, could have spent less time developing elaborate science fiction plot points and more focusing on the emotional core of the show and its characters that make it compelling in the first place.

Weekly Reading List

https://www.routledge.com/Mari-Ruti-and-Climate-Change-From-Grief-to-Creativity/Burnham/p/book/9781032807034 — Clint Burnham has written a fantastic group of essays to wrap up 2025.

https://cdm.link/stewart-copeland-spyro/ — Inspired by AGDQ, this is a great essay on the history of the Spyro the Dragon (1998) score and its famed composer, Stewart Copeland of The Police.

https://kmanga.kodansha.com/title/10653/episode/361325 — Tetsuya Okuyama is trying his hand at a contemporary version of Psycho-Pass (2012).

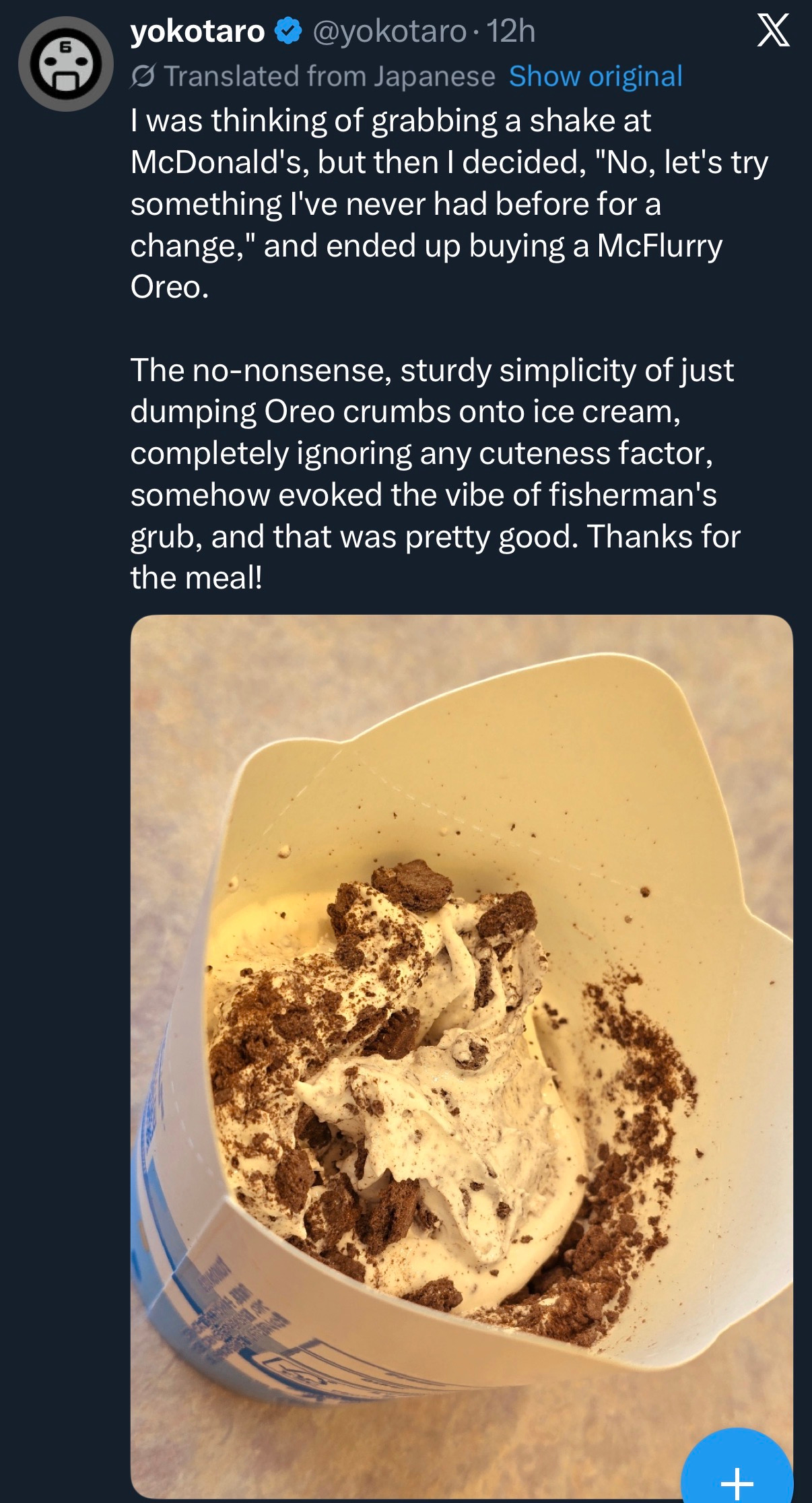

This Yoko Taro review of a McFlurry belongs in a volume of food writing.

Event Calendar: The Brattle in Jan/Feb

Updated with some nice screenings from The Brattle Theater in the first months of the year.

Until next time.