Issue #415: No Other Choice is the Marxist Fable We've Been Waiting For

There’s something in the air. Between No Other Choice (2025), the subject of this week’s letter, and Send Help (2026), it’s the winter of white collar discontent. This is not a totally new idea. We’ve seen it in Falling Down (1993), Office Space (1999), Fight Club (1999), and even American Psycho (2000). In all of these films, something is rotten in the high rises and office parks of the United States. Though none of these films have quite the class analysis of No Other Choice, the overriding ennui and uncertainty of being seated in a cubicle is vivid.

The promotion for the newer films has leaned into the quotidian frustrations. Neon staged a publicity screening of No Other Choice for Fortune 500 CEOs. If they ran the movie at all, it was certainly to an empty theater.

Send Help treated an early screening audience to a rage room. The different vantage points in No Other Choice and Send Help follow from one to the next. When it’s an employers’ market, working conditions are generally worse. There are fewer pinball machines, mental health days, and nitro cold brew taps when there is a dearth of jobs and a surplus of employable candidates.

Films like this, especially No Other Choice, work to translate the long history of Marx’s writing and Marxist theory to a modern economic situation that is, in many ways, inscrutable. More on how, this week.

On Friday (1/23), we’ll be watching What Ever Happened To Baby Jane? (1962) in the Paradox Discord at 7pm Eastern.

It promises to be a good time with some discussion to follow if there’s an appetite for it. If you’d like to join in, you can get a link to the Discord by becoming a paid subscriber.

“I recognize an unemployed comrade at once”: Inevitability and Marxism in No Other Choice

There is a running gag about Freud. Every time some fictional plot, news item, or cultural current reflects the distorted, colloquial view of Freud’s thought, people will post an edited version of screenshot from Breaking Bad (2008):

Whether or not this reaction image correctly attributes certain viewpoints to Freud is another question. But regardless of occasional theoretical incorrectness on the part of the image posters, he does indeed keep getting away with it. He is in fact rivaled only by Marx to the degree that one’s thought is repeatedly substantiated by cultural and political trends. So, for me to be surprised that the adaptation of a 1997 novel, The Ax, proves to be prescient, contemporary, and reflective of the current economic situation would mean I am naive to Marx. He will keep getting away with it. His collaborator, in this case, is Park Chan-wook.

Chan-wook is not simply a conduit for Marxist theory in No Other Choice (2025), his cinematic adaptation of The Ax. For him, Marx’s most important insight is about human subjectivity and collectivity. For the purposes of economic analysis, Marx posits the proletariat as a class with uniform characteristics. Their needs, in the sense of the bottom of Maslow’s pyramid, are discernible based on their class positioning and shared as a class. Members of the proletariat also function interchangeably within a system of wage labor. In Capital Volume I (1867), Marx writes:

The total labour power of society, which is embodied in the sum total of the values of all commodities produced by that society, counts here as one homogeneous mass of human labour power, composed though it be of innumerable individual units. Each of these units is the same as any other[.] (29)

Marx repeatedly emphasizes the collectivity of the proletariat class, going so far as to describe them as “a productive mechanism whose parts are human beings” (238) in the case of industrialization or calling “the workmen” “conscious organs” (283) in a factory with sufficient automation.

No Other Choice extends this symbiotic collectivity to subjective experience alongside the realpolitik significance. Yoo Man-su (Lee Byung-hun) begins as a perfect embodiment of Marxist ideals. Even as a middle-manager, Man-su is class conscious and sticks his neck out for his subordinates. His effort shows his naive belief he himself is immune from being fired, but this belief demonstrates the shared plight of the proletariat all the more. Man-su is fired along with everyone else, the brute economic reality of his position relative to the means of production, but his subjective experience, despite not even recognizing he will be fired, still aligns him with the others who he believes will be fired instead of him.

Man-su’s class consciousness, though, does not come without its qualifications. After he is laid off and begins interviewing, meeting with repeated rejection and plagued by an aching tooth, he justifies the possibility of a less senior role to his interviews by suggesting, “I’ve always considered myself to be blue collar.”

Man-su over-identifies with his subordinates on a subjective level, but this masks his proletariat status. He does not control the means of production and cannot extricate himself from his class vulnerability. In The Holy Family (1844), Marx writes:

It is not a question of what this or that proletarian, or even the whole proletariat, at the moment regards as its aim. It is a question of what the proletariat is, and what, in accordance with this being, it will historically be compelled to do. (51)

What Man-su considers himself is irrelevant to the reality of his economic position and how he chooses to act is subordinate to the necessary action of the proletariat to protect itself from exploitation.

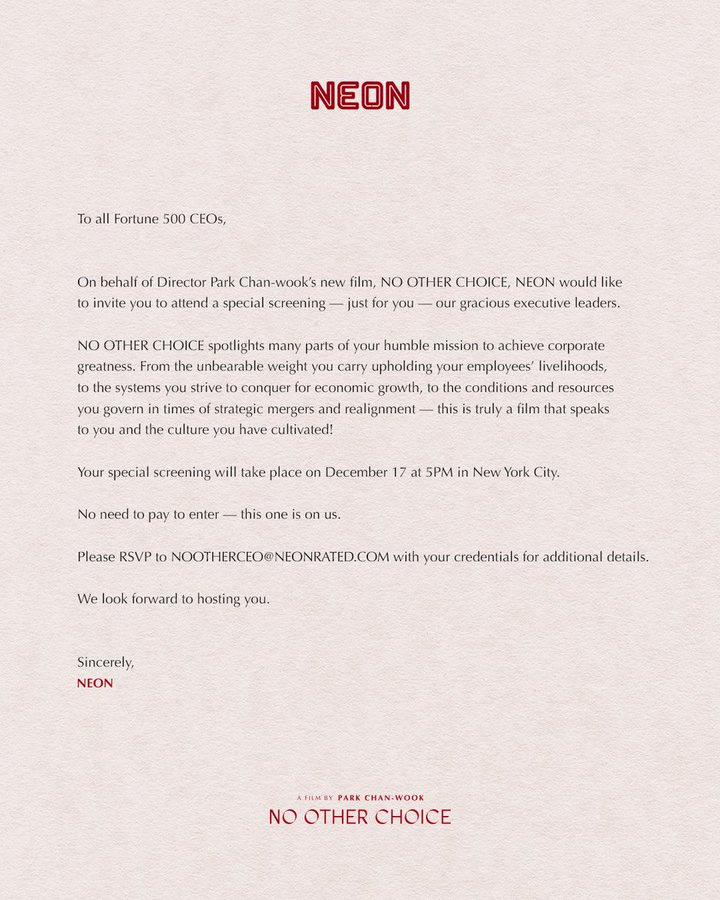

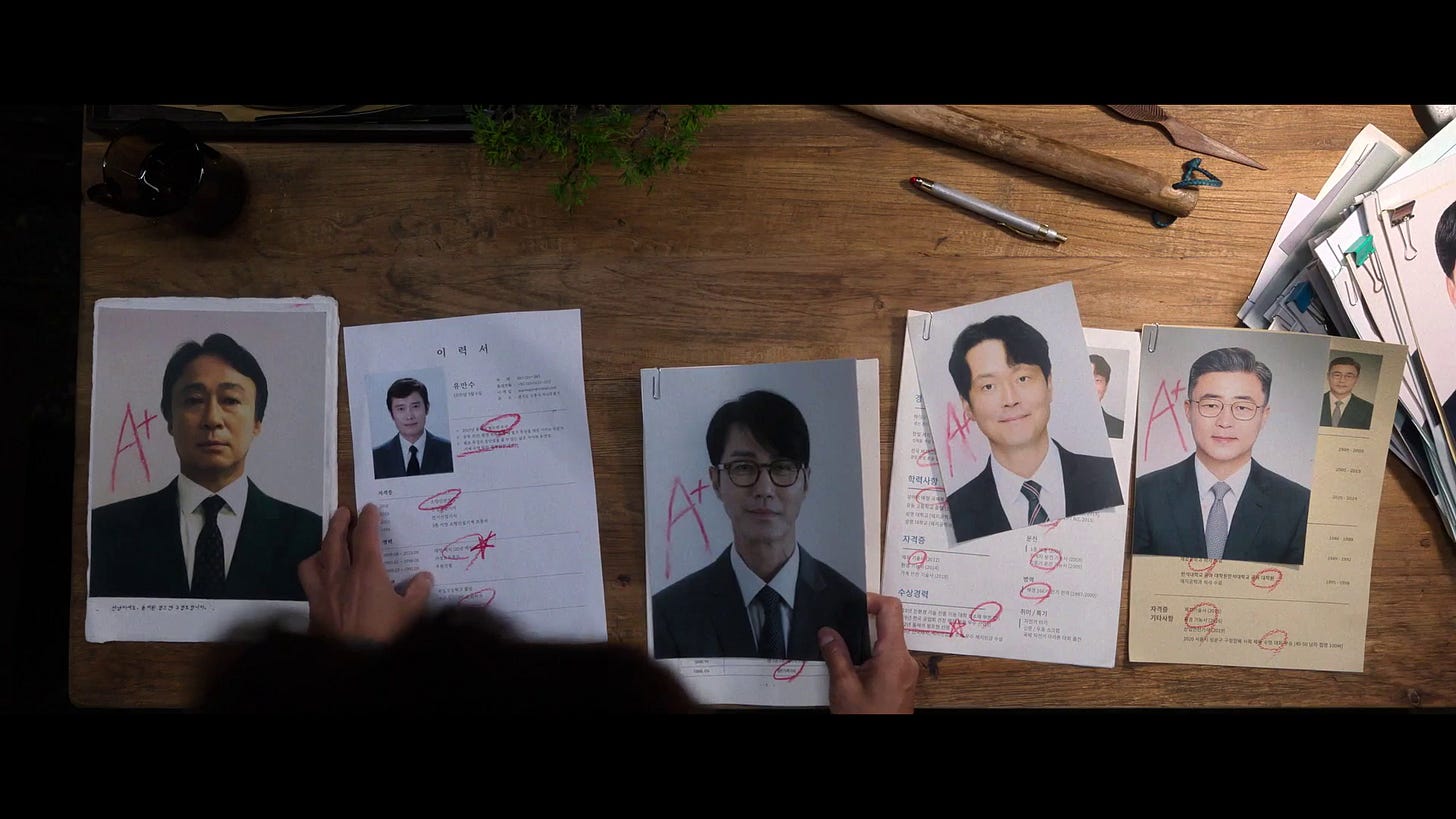

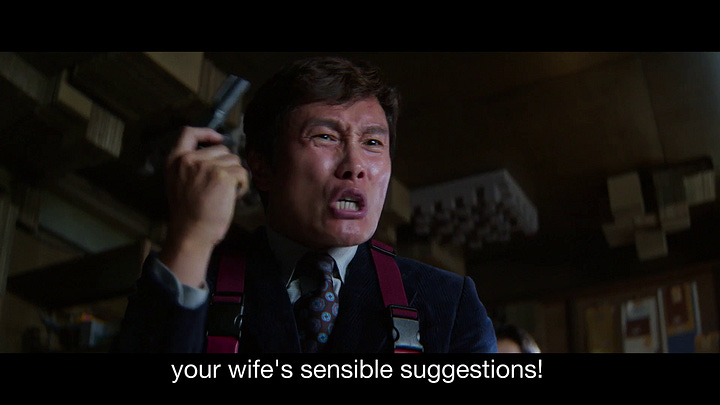

The film’s principal plot is Man-su’s murderous machinations to eliminate competitors for a particular job. He selects them by their qualifications, planning to murder two potential competing applicants and the current job holder, Gu Bum-mo (Lee Sung-min), Ko Si-jo (Cha Seung-won), and Choi Seon-chul (Park Hee-soon).

Necessarily choosing a job for which Man-su himself is well suited, the well-qualified candidates are similar to Man-su. But he underestimates just how similar each man is at the level of the encounter. When Man-su has Bum-mo under the gun, he gives a pep talk, chastising Bum-mo for refusing his wife’s suggestion to explore another profession.

Indeed, Man-su’s condemnation is reflexive, really a self-condemnation. Chan-wook’s script makes this painfully clear:

Man-su finds Bummo too similar to himself, which disgusts him. Frustrated, Man-su waves his gun in the air as he struggles to find the right words.

Even as the film orders Man-su’s action under the auspices of having “no other choice,” the same flimsy and untrue justification of the American corporation that lays him off in the first place, his encounter with Bum-mo evinces most emphatically that, instead of having no other choice, Man-su could do just about anything else other than go on a murder spree.

And he knows it.

From here, the film leans into this self-deception and the affective charge of a brutal encounter between someone with which you are inextricably bound through shared class position and experience. Man-su’s killing of Si-jo is an act Man-su can’t even witness, calling him a “comrade” in their first conversation.

This profound class betrayal and his failure of Man-su to live up to what their camaraderie calls for is precisely the indignity to which capitalism subjects its subjects.

Though Man-su sees himself in a state of exception, this is an illusion projected by late-stage capitalism which uses what the proletariat share to put them in contest with one another and takes irrelevant features of their identity as ascendent over class position.

Ultimately No Other Choice concludes where Marx does not, quite, get away with it. Man-su does get a job but, as Morrissey cautioned, his role as the “human in the loop” for a fully automated paper factory alienates him from the community generated by class consciousness and the vivacity of human life.

There are degrees to which Marx anticipated this state of affairs. Just as the proletariat’s unity is a feature of economic life, capitalism endeavors to divest from the proletariat any specific quality to their work such that any worker can fulfill any required tasks. This returns to the idea of automation and industrialization Marx explores. He writes in the “Manifesto,”:

the work of the proletarians has lost all individual character … He becomes an appendage of the machine (16)

For Marx, this is primarily an issue of price:

The competition thus created between the labourers allows the capitalist to beat down the price of labour, whilst the falling price of labour allows him, on the other hand, to screw up still further the working-time. (Capital Volume 1 384).

What Marx could not have possibly anticipated is the efficacy with which automation, atomization, and alienation would serve to foment competition to such deadly conclusions. We have not yet seen evidence to support the optimism of Marx:

This organization of the proletarians into a class and consequently into a political party, is continually being upset again by the competition between the workers themselves. But it ever rises up again; stronger, firmer, mightier … What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own grave diggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable. (”Manifesto” 19, 23)

At issue in No Other Choice is how the structure of capitalism has totally obscured the possibility of this supposed inevitability, through divesting work from any recognizable human quality.

The inhumanity in question is a plague, a contagion which afflicts Man-su but, as one sees in the closing moments of No Other Choice, spreads to devastate all life.

Weekly Reading List

https://www.humblebundle.com/books/lone-wolf-cub-and-more-koike-encore-dark-horse-books — A huge collection of manga by Kazuo Koike is available from the Humble Bundle. You can get 63 volumes for $18 through the end of the week.

I think you only need a passing familiarity with recent Survivor (2000) players to get something out of the seven episode series of Blood on the Clocktower (2022) games. They are very well edited and as entertaining as anything a television network has come up with. I’m not super familiar with these types of “social deduction” games, but I will probably give this one a shot sooner or later.

Oh yeah.

My ambition was to write an entire essay about this perfect album of Gundam series songs remixed by the best vocaloid producers. I didn’t get to it, but these songs are amazing.

Event Calendar: The US Department of Defense’s Favorite Film

Apparently there is a streamer named “Speed” traveling around the world. I have never heard of him other than seeing clips of his travels, mostly involving children of all nationalities frantically trying to get his autograph. He is also being menaced by an equally unlikely online figure called “White Speed,” who appears to be following Speed across the entire globe and popping out like Majima in Yakuza Kiwami (2016).

If this sounds like the plot of a David Lynch film, or maybe a Harmony Korine, I assure you that the information I am providing is true to the best of my knowledge. But what has been most striking about my brief encounters with Speed’s travel videos is simply the idea that one would travel the globe just to see it. He observes the world with the naive view of someone with little to no political education. This disposition makes sense for someone who has been making a living posting videos of themselves playing video games since they were eleven years old.

In Algeria, Speed remarked on the similarity of the architecture to France. In response, some have recommended him Fanon — I would sooner recommend The Battle of Algiers (1966) screening at The Coolidge in March. This film is having a moment insofar as it dramatizes issues of domestic policing, torture, colonialism, and so on. Both the streets of Gaza and Minneapolis resemble dimensions of Pontecorvo’s Algiers. This is simply a testament to his unparalleled understanding of global conflict.

I used to teach The Battle of Algiers in my First Year Writing classes to think about narrative bias. Pontecorvo’s film has the dubious honor of being screened by the US’s DoD in 2003. I tasked my students with determining what in the film is valuable to both a hegemonic, occupation force and revolutionary organizers.

Also added some other Coolidge screenings to the event calendar, plus some upcoming stuff in the Paradox Discord for our paid subs.

Until next time.