Issue #418: If I Had a Newsletter I'd Compare Schlock and Art Films

In the course of writing about If I Had Legs I’d Kick You (2025) this week, I was disgusted to realize it is only nominated for one Oscar: Best Actress. What is going on here? Someone has to get to the bottom of this.

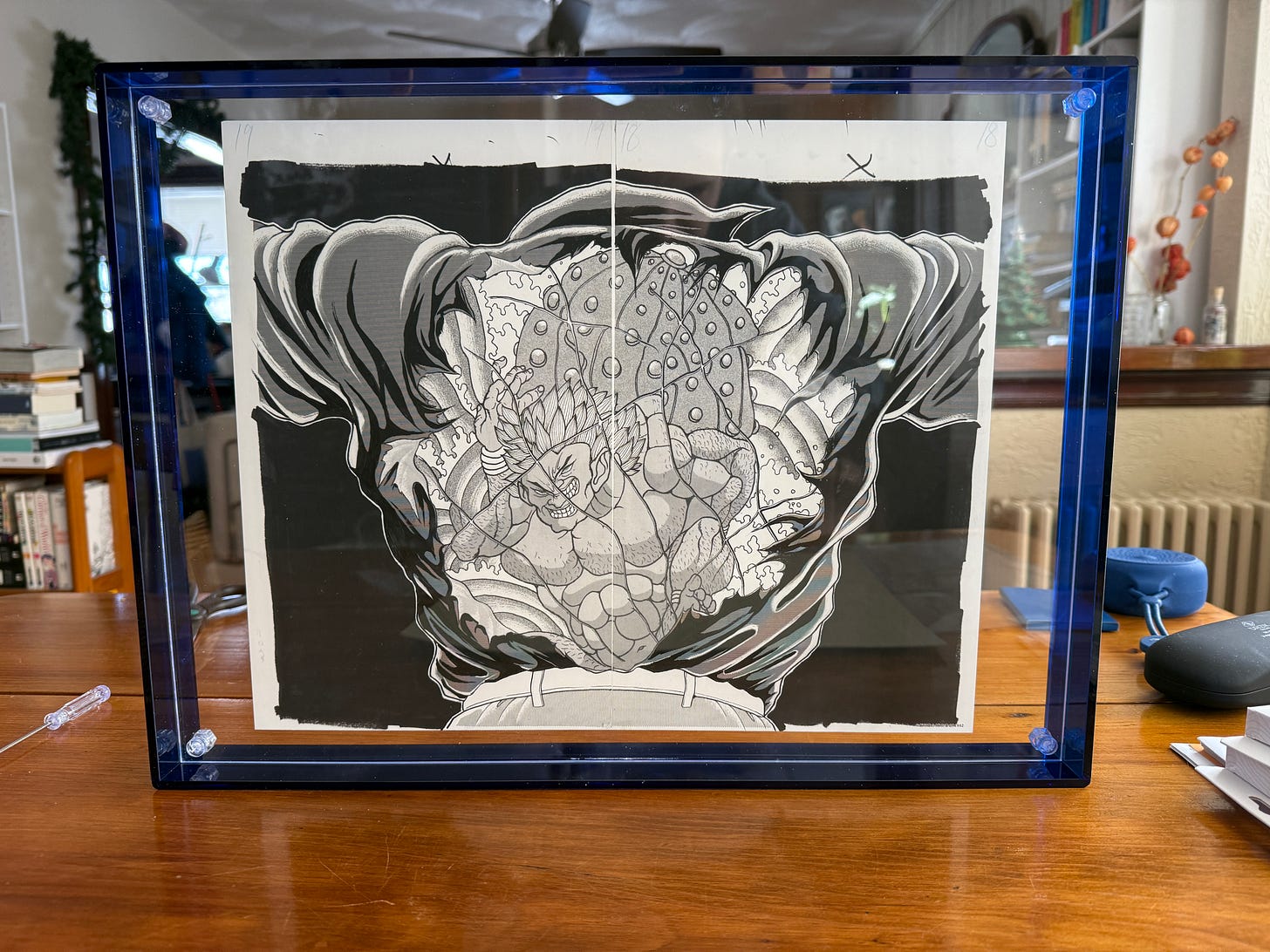

I framed a piece of art from Baki the Grappler (1991) today:

Kodama, Baki’s English language publisher, is selling these. Frame not included. I know I have promoted their beautiful new editions of the manga, but please check them out if you are getting interested in Baki because of my writing about it.

“We’re just walking around pretending we have the power to change something”: The Hell Feminine in If I Had Legs I’d Kick You

It is hard to believe If I Had Legs I’d Kick You (2025) is only Mary Bronstein’s second feature film. But it is neither the mature product of one’s late style nor the lightning-in-a-bottle of a first ever feature. At least, not on paper. Bronstein’s Golden Globe winning and Oscar contending feature has the tendencies of both types of filmmaking. There is a deep, textured cinematic vision Bronstein executes with the unrestrained ambition of an early career filmmaker. Though one might compare it to a great many films, I’ve never seen a single film like it.

One unexpected, though very rich, point of cinematic intersection for If I Had Legs is Frank Henenlotter’s Basket Case (1982). The grindhouse horror film follows Duane Bradley and his formerly conjoined twin Belial (both Kevin Van Hentenryck) seeking revenge against the doctors who performed the surgery to separate them. Like in many films of this ilk, Belial is the libidinous, devouring unconscious to the straight laced Duane. Belial is horrifyingly figured in a wicker basket (hence the title) and an insatiable maw fed obscene amounts of food by Duane.

By contrast, If I Had Legs follows a mother, Linda (Rose Byrne) and her daughter, unnamed (Delaney Quinn) and largely absent from the camera’s gaze. She is a voice and nothing more, at least until the film’s end. Unlike Belial, Linda’s daughter refuses to eat and must be fed through a tube. The antagonism between Linda and her daughter illustrates the altered dynamic from Basket Case. Linda cannot do anything to make her daughter eat, but Duane cannot stop Belial from eating anything. Duane is “normal,” hiding his abnormality behind the visage of Belial. Belial does what Duane cannot, but perhaps would like to. Linda, on the other hand, relates to her daughter in a manner that has fewer cinematic examples. Like Duane, Linda and her daughter once shared a body. However, that time as a shared body, as is always the case with pregnancy, has a necessary termination point. Duane has his desirous other ripped from him, while Linda has adopted the position of the desirous other while her daughter represents desire’s limit. Linda has excised that limit from her, overindulging in alcohol, drugs, and mildly risky behavior because she sees what limits her desire outside of her. At the same time, that limit Linda can see is not one she is subject to.

Critics compare If I Had Legs to the screenwriting work of Bronstein’s husband, Uncut Gems (2019). There is no question they share an aesthetic sensibility that revolves around anxiety and inflicting it upon a film’s audience. Mary Bronstein also explores the human body in a similarly surreal fashion to Ronald Bronstein’s cosmic colonoscopy in Uncut Gems. But there’s something If I Had Legs has that Uncut Gems doesn’t, a formal element that draws to mind Tim Robinson’s Friendship (2024) and I Think You Should Leave (2019). Each scene in If I Had Legs I’d Kick You stands on its own and largely contains everything necessary to understand it outside of the context of the film. The scenes are rich in that way, but unlike Friendship one never gets the sense that they’re meant to be separate. Indeed, they work independently without sacrificing cohesion. As a result, I found the experience of watching the film to be very unusual as the vignettes of Linda’s life form this remarkable assemblage.

This formal quality that is difficult for me to account for also invites a structural analogy between pregnancy and motherhood. Through birth, Linda and her daughter or divided. But their reconnection, the surgical insertion of the feeding tube into her daughter, is a primal scene for Linda which she repeatedly revisits sometimes through staring at a dream-inducing hole in her roof. Linda is entrapped and imperiled by the vicissitudes of womanhood. Not only can Linda get pregnant, a somewhat horrific notion in the film’s logic, Linda is also isolated from others, unable to speak the language of manhood that would significantly ease her movement through the world.

Bronstein’s world (and the real one, too) is one where femininity and the body gendered woman is an affliction. The problems women-subjects encounter are beyond description. Linda, a psychotherapist, works with a woman named Caroline (Danielle Macdonald) who is struggling to care for her healthy child.

Linda watches as Caroline is unable to extricate herself from her child, unable to imagine she is doing more than what is required of her as a parent. Caroline’s husband, by contrast, is so unconcerned with the duties of fatherhood that he refuses to pick up the child when Caroline suddenly abandons him in flight from Linda’s office.

Though Caroline has committed the cardinal maternal sin, Linda identifies with her. She enjoys a momentary abandonment of her child, smoking and drinking near the parking lot while her daughter is alone in a hotel room attached to the incessantly beeping feeding machine.

This ostensible parental irresponsibility is an expression of just how lopsided the domestic responsibilities are in the lives of both Linda and Caroline. Mothers are responsible for the conduct and wellbeing of their child in a way fathers are rarely held accountable. The enforcement of the societal roles are one thing, but the psychic affliction from which women suffer as a result manifests in various forms, including Linda and Caroline’s varied relationships to their children.

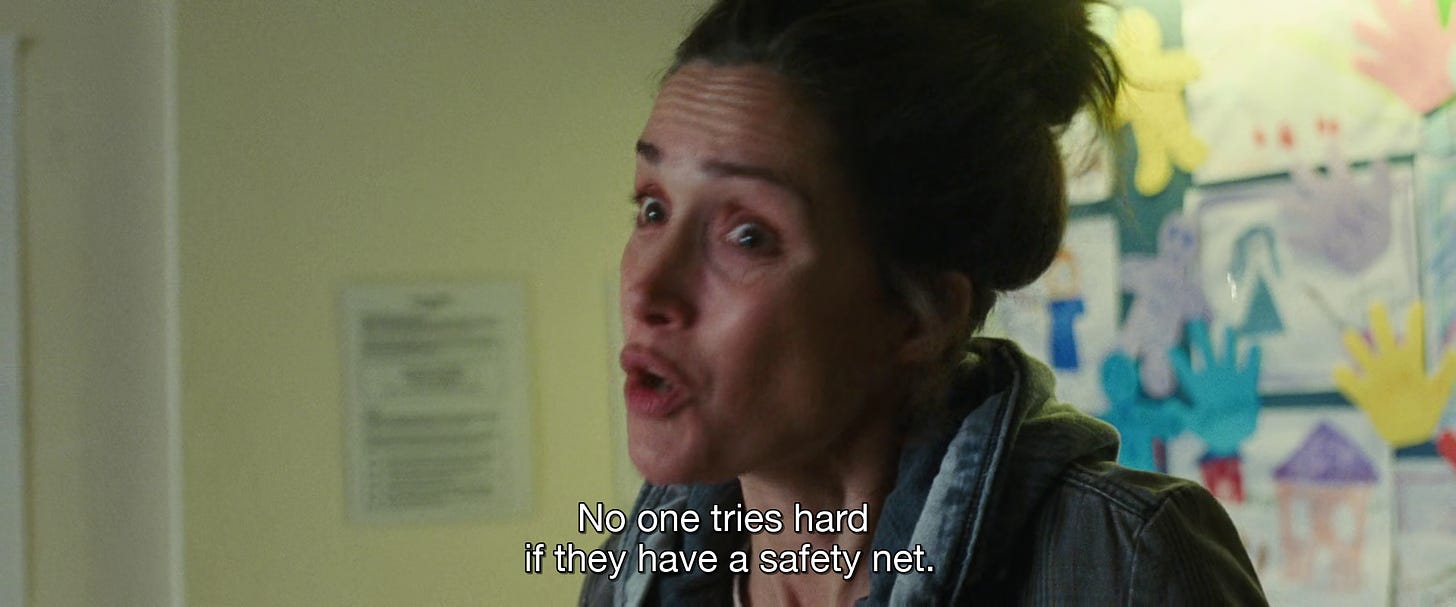

Even as If I Had Legs illustrates the woman’s body as a phobic object for the individual inhabiting it as well as society at large, Bronstein seems intent on rupturing the ideas of social imperilments that one puts upon themselves. Linda’s experience, emphatically gendered, is always depicted as severe and inescapable. By contrast, Linda looks at her own daughter’s problem as fleeting. If only she would just eat. The complexity of her daughter’s disordered (not) eating, for Linda, is seen as a choice that the child could overcome with willpower. Repeatedly, Linda advocates the removal of the feeding tube. She says, “No one does anything hard if they have a safety net.”

And yet, it is no accident Linda’s daughter is a daughter, subject to the same kind of imperilment as Linda, and accordingly much more likely to have an eating disorder than a boy or man.

In my favorite scene in the film, Linda deals with the aftermath of buying her daughter a hamster. Though Linda earlier tells her daughter a hamster is “just something to take care of for no reason,” she eventually gives in and buys the “rodent.” With hamster in tow, Linda’s daughter unleashes it from its box — Bronstein describes this escape as a visual gag and homage to The Shining (1980) in the screenplay.

The metaphor for parenthood is obvious here. And Linda’s daughter’s relative bad luck, “he’s supposed to love me … he hates us … I think we got the wrong hamster,” mirrors Linda’s own frustration with her daughter’s inability (or, from Linda’s view, unwillingness) to eat. As the chaos unfolds, Linda is rear-ended by another car. She has to attempt to calm down her daughter who is screaming hysterically, “we are going to die,” and simultaneously confront the man who hit her, “She thought we were going to die. Don’t fuck with me about my child’s safety. I need all your information.” Finally, the hamster escapes from the “wrecked” car, immediately turned into roadkill.

The hamster scene has it all: the uncertainty of parental existence, the illegibility of the relationship between parent and child, and the two-facedness with which one must face the world in service to that child. Likewise, it shows Linda’s own marginality within a patriarchal structure as she is (once again) condescended to by a man.

There is no redemptive gesture at the end of If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, only pure chaos. Linda goes for her The Awakening (1899) ending, but hell won’t take her. This divided, reviled figure of Linda pledges to do better. How should she? Certainly, the film displays no shortage of effort on her part to overcome the issues of her daughter’s illness, the architectural catastrophe in her home, and her own marginalization. The return of her husband Charles (Christian Slater) and the proverbial suturing of the hole in her roof returns her to a normalcy in which she is so acutely trapped. They have sealed all the exits.

Weekly Reading List

Bad Bunny was cool, but these videos are my Super Bowl halftime show. Man, they’re all looking so old.

Playlist Change Log

Some new songs on the playlist:

“Deadline” — Burning Lord — Burning Lord Split EP

New Burning Lord from last’s weeks split EP with Collateral. First three seconds or so of this song is cribbed from Think I Care, “Burn,” which is a good thing.

“Love Come Down” — Evelyn “Champagne” King — Get Loose

This song is way too good. Don’t even know how to express it.

“The Creator” — Pete Rock & C.L. Smooth — All Souled Out

“Dip dive dip, you might break your hip, to the sound that’s legit”

“Clear” — Cybotron — Enter (Deluxe Edition)

Famously sampled for Missy’s “Lose Control.”

“DOPAMINE” — m-flo, Emyli, Diggy-MO’ — DOPAMINE

I have a love/hate relationship with this song. Emyli’s melody has me levitating but the Diggy-MO’ parts are obnoxious with the weird horn kick from “The 900 Number”/”Let Me Clear My Throat.”

“come again” — Bleecker Chrome — Chrome Season

Somehow I missed this middling Japanese rapper flipping m-flo’s “come again.” Should’ve been Uzi Vert or Nav, but it’s cool.

“黄昏のBAY CITY” — Junko Yagami — 黄昏のBAY CITY

Listen to that bass line.

“Just Another Fool” — Chemical Threat — Promo

The Abused cover. Classic shit.

Event Calendar: John Woo Worldwide

It’s not really worldwide. But in the USA, GKids is running some John Woo flicks across cinemas. Check the links in the calendar for more info on if there’s a screening near you. They are happening widely and AMC screenings are not excluded from A-List. Let’s go.

Until next time.