Issue #364: Narrative Traps and the Unconscious in Severance

Severance is a really funny show. It’s funnier still because despite the absurdity of its premise and all of the ridiculous workplace satirizing it does, it will never match the absurdity of actual corporate workplace truisms. “It takes thirty days to form a habit.” “You have to repeat something three times for someone to grasp it.” These are things that wealthy executives at Fortune 500 companies actually believe. Yes, you can be a millionaire and live your life in accordance with repeatedly debunked pop science. There’s a book idea here. Maybe I’ll come back to it.

As for Severance, I’m not sure how many newsletter installments it takes for me to form a habit, but I think I will be writing about it until the end of the season.

The show has done something remarkable, too, in its promotion. Though grabbing the “zeitgeist” is something all television shows aspire to, Severance is the first I’ve seen that so self-awarely leans into the idea of theorizing about the show. I don’t mean actual literary criticism, of course. I mean speculating about what will happen, what are the “hidden” elements of the plot, that sort of thing. There are a ton of youtube videos dedicated to this topic, I even watch some from time to time.

And while videos involving stars of whatever sci-fi puzzle box commenting on this kind of speculation are not uncommon, Severance is the first example of the actual network that airs the show producing such a video.

Cliffhangers have any number of crass incentives for their inclusion in a serialized work. They will bring the audience back next week to resolve the uncertainty. They can be used for contract negotiations when they occur at a seasonal break. But plot mysteries, like the ones in Severance, can also command people’s attention in the same way. Both narrative elements mean that there is something the audience doesn’t know, some element that is unresolved.

I think Severance is a good show, but there’s a cynical view that any television show might choose to ramp up its mysteries in order to keep audience attention rather than serve some other artistic purpose. Whether Severance falls into such a trap remains to be seen.

“A Cure for Mankind” in Severance’s “Goodbye, Mrs. Selvig”

In the second episode of Severance (2022) season two, Helena (Britt Lower) delivers an apology for the outburst of her work-self1:

I’m committed to this company with every part of me. But I’m also human. Just like my innie… and just like you.

The structure of this apology reveals a lot about the position of the two constituent selves, the so-called “outie” and “innie” (two lore jargon phrases I will now avoid like the plague), in Severance. But more than that, it reveals something about humanity. Immediately following the statement that she is “committed to this company with every part of” her, she says that she’s “also human” following a “but.” The structure of these two sentences means her being a human represents a contrast to her commitment to her company, Lumon. There are a few ways to read such a distinction.

One is simple: humans are flawed, so they may not always act in accordance with their interests or deeply held commitments. Another reads her first statement against the grain and gives her apologia for her humanity a psychoanalytic spin. Despite being committed to Lumon, one who is human will never succeed in orienting every part of themselves in support of the same convictions. The Freudian unconscious makes this certain.

Freud defines the unconscious in the most elementary terms in “The Unconscious” (1915):

We have learnt from psychoanalysis that the essence of the process of repression lies, not in putting an end to, in annihilating, the idea which represents an instinct, but in preventing it from becoming conscious. When this happens we say of the idea that it is in a state of being ‘unconscious’, and we can produce good evidence to show that even when it is unconscious it can produce effects, even including some which finally reach consciousness. (167, Strachey trans., 1984 Penguin edition of On Metapsychology)

The notion of the unconscious is exposed by the mechanic of repression, and from Freud’s vantage point at this time, inextricably bound to it. Freud goes on:

The unconscious comprises, on the one hand, acts which are merely latent, temporarily unconscious, but which differ in no other respect from conscious ones and, on the other hand, processes such as repressed ones, which if they were to become conscious would be bound to stand out in the crudest contrast to the rest of the conscious processes. (174)

Freud seeks to resolve an ambiguity here: some thoughts or acts move from a state of unconscious to conscious thought regularly, while others influence one’s ego through obscure and oblique means fixed within the unconscious. The unconscious is not an alternate personality, a distinct subject, or a severed self. But it is another agency within the subject, and its capability suggests that the subject is never coherent and unified in its orientation toward demand (a stated commitment) and desire. To bring this back to Helena’s apology, what she apologizes for in this case is her unconscious, a necessary part of her humanity.

This leads to yet another important point. In some texts involving doubling, alter egos, doppelgangers, or any other variety of mirror self, that other is meant to represent the unconscious. They embody desire, unrealized fantasy, and present a negative image of what the subject believes themselves to be lacking. Not so in Severance, where the connection between the work-self and outside-self are ambiguous. Indeed, instead of being a part of the previously existing “outie’s” psychic life, the “innie” emerges through the process of severance as another subjectivity entirely, someone who is “human,” just like Helena. Though her apology is a lie through and through, Helena herself is prejudiced against “innies” and doesn’t believe them to be human, her lie reveals the truth of the show itself: the work-self is not a simple embodiment of the unconscious but an alternate self that has a complicated relation to the outside-self.

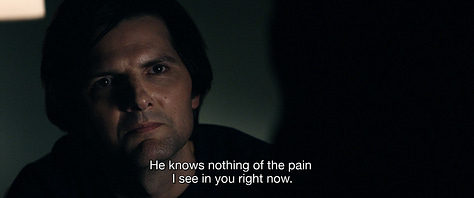

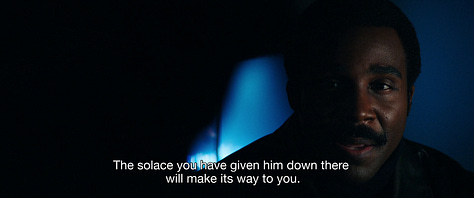

The selling point of the severance procedure within the show is that the two are separated inexorably, never the twain shall meet. But in “Goodbye, Mrs. Selvig,” the “outie” perspective shows just how much the action of those who live only on the severed floor impact those who exist outside of it. In a conversation between Mr. Milchick (Tramell Tillman) and Mark Scout2 (Adam Scott), Milchick tries to entice Mark to return by a continuity between his “innie” and himself:

The Mark I’ve come to know at Lumon is happy. He cares for people and he’s funny. He knows nothing of the pain I see in you right now. He’s found love. The solace you have given him down there will make its way to you. It just takes time.

This is a bizarre reversal of what severance promises: an absolute, unassailable division between wage-labor and everything else. Because Mark S. is happy, Mark Scout will become happy. Severance’s viewers know Mark S. isn’t the happy camper Milchick is describing him as — though Milchick may well believe it. His promise to Mark Scout, that he will feel the solace of his wage-laboring persona, could also be every bit the lie of Helena’s apology. But Severance has repeatedly emphasized that the cut between the selves is not so clean. One brings with them the immediate sense feelings of the office when exiting it, for instance, something highlighted in “The Lexington Letter” (2022).

One might imagine that Severance would be a far less appealing procedure if what it promised was enrichment through the activity within the workplace. Typically, people like to be conscious of the events that bring them pleasure and make them happy. Milchick, here, reverses severance’s promise. Mark Scout isn’t outsourcing his banal, painful, meaningless-yet-necessary laboring, but his healing from the trauma of his wife’s death. In a corollary symbolic logic to The Substance (2024), one subject acts in service of another’s good fortune even if they don’t get to experience it themselves — simply because one subject is derived from the other (there’s a parenthood analogy available here, too).

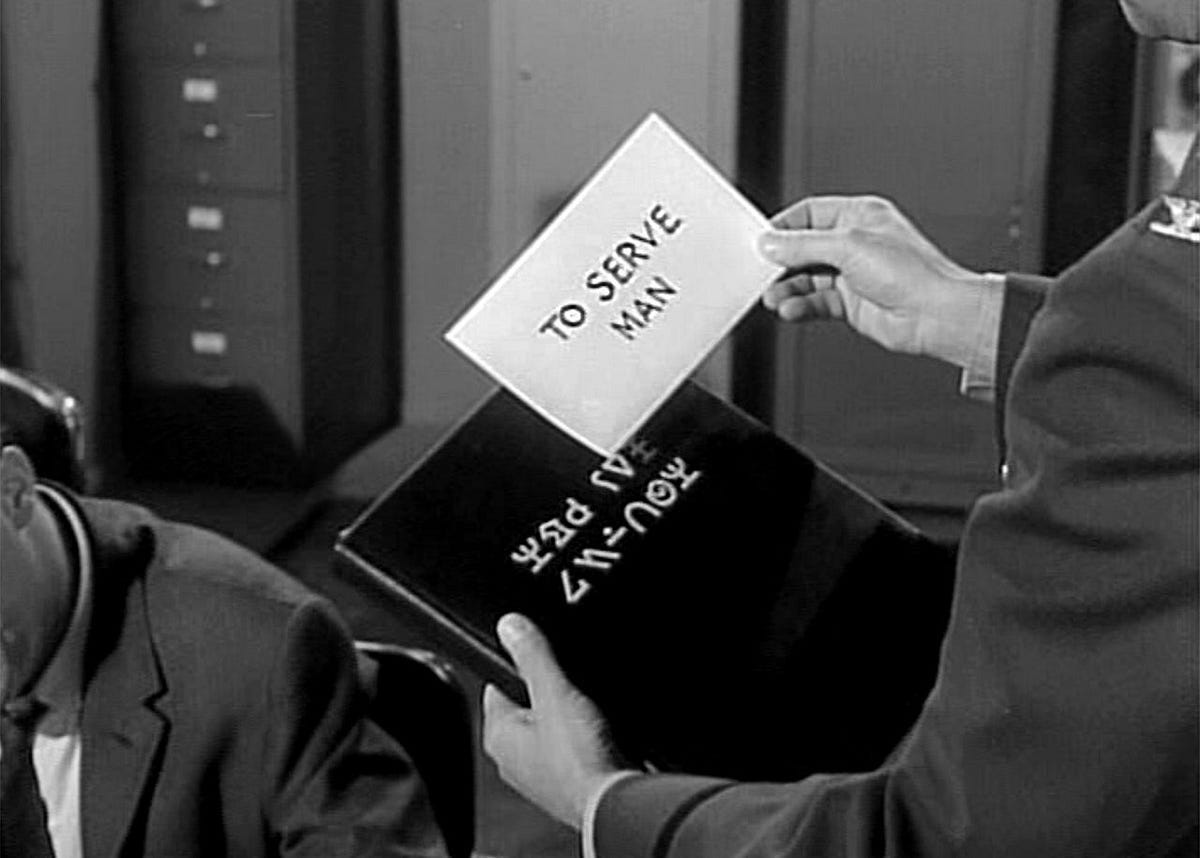

Mark S. isn’t simply a reflection of Mark Scout’s unconscious. But perhaps the two share one as the necessary condition for humanity. The space of the unconscious is where the activity, disposition, and feelings of the “innie” can intervene on the life of the “outie” and vice versa. Severance poses the question of what it means to be human acutely in this episode, and returns to a phrase that calls into question Lumon’s relationship to humanity: “Remedium Hominibus.” The Latin phrase means “a cure for mankind,” and Latin grammar does suggest this should read benevolently. What is being described is a cure for mankind’s use, not a cure for a disease named mankind (“hominum,” in place of “hominibus,” would more likely describe a cure for mankind like a cure for cancer). But forgive me if I’m not so sure Severance’s writers are rigorously adhering to Latin grammar. “A cure for mankind” is all too evocative of that brilliant Twilight Zone (1959) twist where aliens arrive with a cookbook: “To Serve Man.”

If Helena’s apology is any indication, human frailty as a bulwark against true commitment is problematic for the cult-like Lumon corporation. And a cure for mankind, whether it’s hominibus or hominum, may spell the end of whatever quality makes Severance’s characters human.

Is Rurouni Kenshin’s ‘Kyoto Arc’ the Most Adapted Manga/Anime Ever?

As of 2023, Rurouni Kenshin is back on television. The storied manga and anime has been revived by director Hideyo Yamamoto, and writer Hideyuki Kurata. The 1996 anime is a critical work for the emergence of anime in the United States, televised on Cartoon Network’s Toonami block in 2003. This new adaptation returns to the source yet again, maintaining fidelity to Nobuhiro Watsuki’s 1994 manga.

After the success of the first season, Yuki Komada took over for Yamamoto as director reaching a critical point in the mythology of Kenshin, now titled Kyoto Disturbance. The “Kyoto Arc” involves a confrontation between Kenshin Himura (Soma Saito/Howard Wang in the remake) and Shishio Makoto (Makoto Furukawa/Mick Lauer), both government assassins in the period of the Bakumatsu.

Now, on opposite sides of a coup attempt against the government they both served, Kenshin and Shishio have to duke it out in Kyoto for the fate of Japan. It’s an exciting story setup with a strong historical critique. It also provides a great opportunity to explore Kenshin’s character who has since taken an oath not to kill — he’s Japan’s Batman. For Batman, the question is so often whether or not his deontological moral conviction is preferable to a utilitarian calculous that might suggest some villains should indeed be killed. In Rurouni Kenshin, things are a bit more existential. In the 33rd episode of the remake, “Drawing of the Forbidden,” Kenshin recalls a conversation with the sword smith Shakku. Shakku says to Kenshin:

You’ve slain too many men. You can’t run away from it now. Live by the sword, and die by the sword. You can search all you want but for you, there is no other path. … Try being a swordsman with that around your waist. I bet it won’t take long for you to see for yourself just how naive you are. But if you still believe in all that sweet-sounding nonsense even after that thing’s been broken, well, then come back to Kyoto and pay me a visit.

The “that thing” to which Shakku refers is Kenshin’s signature sakabatō, literally “reverse-blade sword,” where the cutting edge is on the inside facing toward the wielder and the blunt edge is on the outside. The question of the Kyoto arc is whether Kenshin’s “sweet-sounding nonsense” can overcome the totally unbridled lust for power of Shishio.

This must be a reasonably compelling story. Along with the 1994 manga, the 1996 series, and the new 2023 series, the Kyoto arc has been adapted twice more. The first is yet another animated adaptation released in two parts starting in 2011, Rurouni Kenshin: New Kyoto Arc. The second and third installments of the Rurouni Kenshin live action film series also adapt the Kyoto arc, Kyoto Inferno (2014) and The Legend Ends (2014).

What makes this story worth being told again and again? For one thing, Kenshin and Shishio are very potent foils. Shishio’s ideology of “might makes right” has a potent resonance with the Meiji Restoration and all the anxieties about foreign subordination it involves. It’s a story that taps into the wake of Japanese political modernity.

No anime has captured samurai drama like Rurouni Kenshin. If someone could get around to animating Vagabond (1998), maybe Kenshin would be unseated. But Rurouni Kenshin is a archetypal shounen manga with historical and philosophical depth and is at its deepest in the Kyoto Arc. No wonder creators keep going back to that well.

Weekly Reading List

This moon landing was not fake.

This series won’t be out until April, but it’s going to be amazing.

Jessa Crispin’s is the last word I want to hear about Neil Gaiman. Her essay here is phenomenal.

Until next time.

Trying this on as an alternative to “innie.”

Another way to distinguish between the “outie” and the “innie” is by use of the surname, “innies” only use a beginning initial and never learn their full last name.