Issue #370: Severance's Shortest Episode Cuts Deep

I got new business cards made for LACK. I’ve had business cards for the extent of my professional academic life, courtesy of my wife Erin. I think people might underestimate their efficacy, but you do have to be willing to grant yourself a little bit more of a carbon footprint.

The conference starts this Thursday, with more details on my presentation and others I’m looking forward to here:

This week, I deliver some quick reviews of a bunch of TV shows you probably aren’t watching and my case for Avowed as game of the year. And, as always, some analysis of the latest episode of Severance.

The Healing Cut of “Sweet Vitriol”

I don’t usually give qualitative reviews of tv episodes, though I have been finding myself doing so more and more as part of my writing about Severance (2022). This week’s episode, “Sweet Vitriol,” demands this kind of commentary more than most. Among the fan community, it has been polarizing. Critical response has been anemic. The episode is shorter than most. It deals exclusively with Harmony Cobel (Patricia Arquette) and a heretofore unseen supporting cast. But it delivers a familiar kind of plot development for Severance, answering a question that the audience wasn’t clamoring for an answer to. To my mind, answering these questions and making the answers feel exciting and meaningful is one of the show’s strengths.

Let’s not beat around the bush, “Sweet Vitriol” reveals that Cobel is the inventor of the severance procedure and associated technology. While I did mention the idea that inventors are often metonymically credited for the work done by people in their employ, it was never urgent to me that I know who exactly invented severance. I felt similarly in season one about the revelation of Helly’s (Britt Lower) identity in “The We We Are.” As a viewer, I didn’t feel like details of Helly’s (or Irving’s [John Turturro]) “outie life” would be critical to the overarching plot. At the same time, knowing who Helly is retroactively changes my perception of her entire story. As early as the first episode, Milchick’s (Tramell Tillman) reverence for Helly hints at her identity. Cobel’s history is at least structurally similar. Her investment in the severed floor and her demand to be floor manager (in “Goodbye, Mrs. Selvig”) are more meaningful in light of her inventing the technology in the first place.

This episode’s structure is both uncommon in the history of television serials and adds to the show’s thematic richness. “Sweet Vitriol” does the work of a flashback episode despite keeping the episode’s manifest plot on the ever-progressing contemporary timeline. We can see in this explication an example of Molly Anne Rothenberg’s formulation of retroversion. In The Excessive Subject (2010) she writes:

I strike a stationary billiard ball with a cue and it rolls into the corner pocket. First comes the cause, then the effect. But retroversive causality challenges that linearity, as if the act of striking the ball into the pocket could loop backward in time to change the initial position of the ball on the table. Of course, physical forces at human scale rarely exhibit retroversive causality, although physicists describe the quantum world as a phantasmagoria of such phenomena. On the other hand, social forces seem always to exhibit retroversive causality, precisely because they necessarily involve signification, meaning, or interpretation. As soon as we have a social situation, we are in the world of signifiers: the signifier is always subject to the law of retroversion. Clearly then, once we notice the phenomenon of retroversion and try to take it into account, we face the difficulty of defining the concept of “change.”

In short, Severance viewers gain a better understanding of what the events of the past mean not by viewing them as they happened, through a flashback, but by their distant result that retroactively defines them. It is only with the visceral view of the “market readjustment” and “retrenchment from some of the core infrastructure investments” that we can make sense of what is significant about Harmony Cobel and Hampton (James LeGros) stirring the ether vats as children.

As a framing principle for the episode, it’s clever. Shows so often resort to the flashback episode, something Severance availed itself of with “Chikhai Bardo.” But the flashback episode often needs some contemporary plot grounding, intercutting the current events of a show with these past recollections. “Sweet Vitriol” does away with the flashback entirely, but it conveys all the expository details that are often delivered through flashback.

This is an insistent recurrence of the kind of plot twist Dan Erickson seems so fond of. Whether it’s Helly’s identity in season one, Helena’s impersonation in season two, or Cobel being the inventor of severance in this last episode, each redefines and recontextualizes the behavior of the characters in previous episodes. Among the three twists, however, Helena impersonating Helly was the most telegraphed, different from Helly’s identity and Cobel’s accomplishment. It’s this delicate foreshadowing, but lack of obvious telegraphing, that I think is part of what makes audiences more dissatisfied. They want answers to the questions they have asked, not the questions they didn’t think to. But just delivering the answers one expects would make a show as empty and uninteresting as any number of plot driven thrillers with obvious twists.

“Sweet Vitriol” is similarly careful about getting across important information to the viewer that isn’t immediately relevant to the plot. Last week, we saw the vantage point of the MDR monitors who communicate when in the show’s timeline the experiments on Gemma are happening. Specifically, Mr. Drummond (Ólafur Darri Ólafsson) reference Mark’s (Adam Scott) nosebleed, something that happened in the episode immediately prior. Devon’s call to Cobel situates us in time the same way. We know the call is coming after the conclusion of “Chikhai Bardo,” and, even better, Cobel doesn’t answer the call until we as an audience know where her sympathies lie. The ambiguity of whether Cobel is sympathetic to Mark could have been used as a source of tension. But the show, mercifully, spares us.

There’s a continuity one can trace from the unethical business practice of child labor to the unethical practice of severance. Lumon’s exploitation is seemingly without limit. It is also continuous, with the avatar of child labor persisting in Miss Huang (Sarah Bock). She is seemingly in contention for the same “Wintertide Fellowship” Cobel was awarded.

What Lumon seems poised to sell, above all else, is pleasure. Ether and severance are allegories for one another. The testing of Gemma is ostensibly for a use case of selling severance as a consumer product that can insulate someone against the unpleasantness of everyday trials like air travel or dentist appointments. But the supposedly undifferentiated pleasure of severed life has a cost. Petey says in “In Perpetuity,” “you carry the hurt with you. You feel it down there too. You just don’t know what it is.” Here, he’s referring to Mark Scout’s grieving being felt by Mark S. But the opposite is also true, the hurt accompanies the severed to their outie. Ether’s downsides are a bit more obvious, as we see the consequences of abusing the drug. Lumon will always extract a cost for the pleasure they provide.

There is a logic that governs this value extraction. The logic of capitalism, of course. But also the logic of a repeated Lumon-ism, “you must be cut to heal.”

There are all manner of cuts in Severance, in different vernaculars, but most important is the titular severing. On it’s face, the idea “you must be cut to heal” is simply an account of the dialectic of hurt itself. This dependency, healing coming only after hurt, is why Pokémon (1996) players have chafed against Nurse Joy’s declaration, “we hope to see you again,” as if implicitly hoping for pain to be inflicted on one’s Pokémon to occasion that seeing.

But, more specific to Severance, the procedure itself is a cut that heals. According to Milchick and Lumon, severance can resolve the pain one experiences, even to the extent that Mark will alleviate his feeling of grief through the “solace” his innie finds. This is the contradiction Severance is tenacious in bringing to the foreground. The ultimate healing requires a profound, irrevocable cut that excises pain itself. It is a cut that, ironically, never heals.

I Am a Machine That Turns TV Episodes into Writing About TV Episodes

Aside from Severance, I have dipped my toes into a range of prestige, mostly streaming, TV shows. This machine gun review will hopefully guide you toward the best and away from the worst.

Paradise (2025) 👍

I think it’s pretty widely believed that Sterling K. Brown is one of our great untapped acting talents. He was excellent as Clifford in American Fiction (2023), but I know him best as an exceptional character actor: Thomas Biggs in Without a Trace (2002), Todd Gillis in Medium (2005), he had a four episode arc on Supernatural (2005), and a six episode arc on Person of Interest (2011). I was a fan of him in his short-lived regular cast stint in the underrated Starved (2005), but his true breakout performance was as Christopher Durden in American Crime Story: The People v. O.J. Simpson (2016). He brings prosecutor Durden to life.

So, Paradise is his really, really big break. In Starved and O.J., he was part of an ensemble. Now, he’s the guy. He’s a perfect fit for the surly, disillusioned lead of a former president’s barebones Secret Service detail. Paradise in its first episode appears to be every bit the straightforward political thriller of Scandal (2012) or House of Cards (2013), but an 11th hour twist suggests the show is more than it appears. Paradise works with one style of storytelling that is a light touch when it comes to foreshadowing. I wouldn’t have guessed its final turn.

Prime Targets (2025) 👎

This show is about some kind of conspiracy that has to do with, ostensibly, advanced mathematics. Unfortunately, it suffers from the same verisimilitude straining plot device as a show that includes a musician or band. If the audience is expected to believe that a band is exceptional, but their music is only so-so, it’s a challenging conceit to get across. Leo Woodall gives an unconvincing performance as a guy scribbling a bunch of shit on tablecloths and walls, none of which is at all convincing as maths worth killing over. Pass.

Slow Horses (2022) 👎

This show has been running for years, so I guess some people must like it. I don’t. It was neither thrilling nor funny.

Dark Matter (2024) 👍

Dark Matter is a high concept sci-fi thriller starring a guy who looks concerningly similar to John Cusack. Since this show is about a guy encountering various dopplegangers of himself from parallel universes, it would be funny to have one actually played by Cusack. Instead, Joel Edgerton as the many faces of Jason Dessen comes across fine. In contrast to Paradise, this show’s first episode hinges on a twist that teeters between obvious and self-evident, the latter if you looked at even one single promotional image for the show. Not great for the episode’s thrills, but I like the show enough to keep watching.

Presumed Innocent (2024) 👍

It’s a pretty hard sell for me when a show centers its tension on whether or not a main character’s wife finds out about that main character’s infidelity. I was pleasantly surprised, then, that this Jake Gyllenhaal vehicle didn’t subject Ruth Negga to such indignity. This show feels the most like a classic HBO mini series out of anything I’ve seen recently. Gyllenhaal is in his Nightcrawler (2014) bag with this one.

Zero Day (2025) 👎

This is garbage. Everyone involved is debasing themselves.

The Hunting Party (2025) 👎

The Blacklist (2013) at home. It’s almost commendable how obviously this show attempts to replace the impressive ten year TV run James Spader put on his back. I don’t think this one will make it to season two, but Melissa Roxburgh is a great leading woman.

Daredevil: Born Again (2025) 👍

I am a huge fan of Vincent D’Onofrio from his time on Law & Order: Criminal Intent (2001). Excluding the cast of Homicide: Life on the Street (1993), D’Onofrio delivers the most compelling police procedural performance in history and created a mold Mandy Patinkin could fill during his one season run on Criminal Minds (2005).

Somehow I also have become a huge fan of Charlie Cox despite basically hating the Netflix Daredevil (2015). I think if you measured the duration of one-on-one conversations across Daredevil’s three seasons, you would find that they amount to a much larger share of runtime than any decent television show.

Thank god Born Again showrunner Dario Scardapane seems intent on fixing that. In an interview with GamesRadar, he highlighted the earlier show’s failing, “[a]t its worst, it was two characters in a room talking about what a hero is.” One-on-one conversations are kept to a much more reasonable share of the screen time in Born Again. I’m all in on this one. 9pm on Tuesday is taken for the next seven weeks.

Running Point (2025) 👎

Despite my love for Max Greenfield and basketball, this show is bad. Straight forward comedies suffer when the characters are subjected to nothing but hardship after absurd hardship.

Suits LA (2025) 👍

Critics have derided Suits LA for being too dissimilar to Suits. Its real flaw is that it is too much like Suits (2011). It has the same tired plot structures, the same unnecessary drama, the same vocal cadence Stephen Amell borrows from Gabriel Macht. If you liked Suits for what it was instead of in spite of what it was, you will like Suits LA. As it turns out, most people who made up the Suits streaming boom were part of the latter category. I think Suits LA will be cancelled, but that’s too bad. Because, somehow, I like it. Maybe I appreciated the formula of Suits more than I thought.

The right decision by Aaron Korsh, if he wants to keep the cast and crew of Suits LA employed, is to figure out how to get one or two original cast members of Suits as LA regulars right away. Otherwise, this is a guaranteed one-and-done.

The Unforced Choice of Avowed

Avowed (2025) is a very, very good game. I think, to really understand why it is so good, it helps to consider some of the challenges that are presented by two design elements, non-linear storytelling and player choice.

A game is more difficult to make in direct proportion to how non-linear it is and how much player choice it involves. There are a number of approaches developers have used to overcome these challenges. Romancing SaGa 2 (1993), which I think should be required study for any game dev working on a game with non-linear storytelling and player choice, solves this problem by making its story simple. The narrative is uncomplicated, but the story is endlessly dynamic and will unfold very differently depending on the order one tackles different biomes and bosses. There are also meaningful, hard hitting choices the player will make that aren’t obvious. The consequences of what the player chooses to do and how they choose to approach the game’s challenges will matter a lot in ways the player can’t predict.

Chrono Trigger (1995), by contrast, presents a more complex story but resolves the issues of non-linearity and player choice by encouraging the player to play the game multiple times and experience all the gameplay routes. Chrono Trigger, in fact, requires that the player play through multiple different endings to obtain the “true” ending. Its linearity and choice, in this sense, are illusory as the player will eventually make a wide variety of different choices to get to a unique outcome that isn’t possible in a simple playthrough. This is a pretty common approach to finding a way to pace a game’s narrative while still letting the player have some flexibility in how they experience it. The Nier series and second installment of the Zero Escape series, Virtue’s Last Reward (2012), also use this structure.

The BioWare model of player choice is a little less compelling. In Dragon Age: Origins (2009) and Mass Effect (2007), the game has an alignment system which displays the moral value of player choices. Unfortunately, to keep their plots well paced and compelling, they sacrifice meaningful choice. Chrono Trigger makes its choices illusory in the grand scheme of things because the player will see the outcome of every choice. Mass Effect and Dragon Age are designed such that the player will only experience one outcome, but each possible outcome isn’t very different from another. The games are great, exciting narratives, but they don’t deliver on their promise of player choice.

Avowed seems to draw from both Romancing SaGa 2 and Dragon Age, by keeping the overarching narrative linear but providing consistent, meaningful choices to the player that seriously change the plot. Like Romancing SaGa, it’s rarely clear when one is making a choice that will have significant impact. Even more impressive, the choices sometimes compound, where possible options exist only because of specific choices the player made prior.

As a work of storytelling driven by player choice, Avowed is a marvel. The reasonable sacrifice of non-linearity is a testament to just how challenging it is to execute on these kinds of games. Avowed is similar to Bethesda’s The Elder Scrolls series in terms of gameplay and setting, but Avowed is so much better than a Bethesda game in the scope and impact of the choice it provides the player. Bethesda would be better off dedicating themselves to make the most radically non-linear game possible instead of competing with Avowed.

Finishing up my time with Avowed, I wonder how wide the band is of actions I could’ve taken that the game seems to endorse. During my play through, I veered into territory that, clearly, the narrative discouraged. But I think that’s a good thing. A game shouldn’t treat every option the player can pursue as equal. If a character does something morally bad by the game’s logic, the player should suffer consequences. Avowed is great about this without being too heavy handed.

The game follows an imperial envoy of Aedyr, a dominant nation seeking to colonize The Living Lands, an untamed wilderness occupied by a disparate group of settlers who have, at one time or another, fled from their ancestral jurisdiction. The envoy allies themselves with a variety of Living Lands residents and the game presents a wide range of possibilities for governance of The Living Lands, ranging from independence to complete subjugation. Between the two extremes is an extraordinarily fine graduation of different forms of colonial governance.

My one criticism of how the game’s story and choices worked together is that there’s clearly a version of the protagonist that’s a loyal, if conflicted, Aedyrean. I don’t think the game gives the player any reason to feel anything good about Aedyr, but I’m not sure if that’s by virtue of me not playing the preceding Pillars of Eternity titles or what I was looking for simply wasn’t there. It’s not a problem that is easy to fix, but perhaps one Aedyrean companion who is very likable could go a long way. Still, given that so many of the choices in the game involve some version of “do this thing that’s good for Aedyr because you believe in the kingdom’s principles,” I didn’t find those avenues very compelling. It’s also possible my sympathies for independent nation states are just too great.

I will be shocked if I play a game this year that impresses me more than Avowed. For fans of the gameplay it offers or games that give the player undeniable agency, it is a must play.

Weekly Reading List

A nice rendition of the Severance theme.

Go deep on Magic competition lore this week with a retrospective of the career of the notorious Mike Long.

Postscript

I am getting to the point where I feel a little self-conscious about my “in memoriam” segments that periodically pepper the newsletter. What I consider is the fact that no matter how conscientiously and prudently one may live, there are unexpected statistical improbabilities that are impossible to avoid. What I also consider is that my friend, Neichelle, asked me regularly, and without prompting, about the newsletter in what I didn’t realize was her final year of life. It seems only right to memorialize her here.

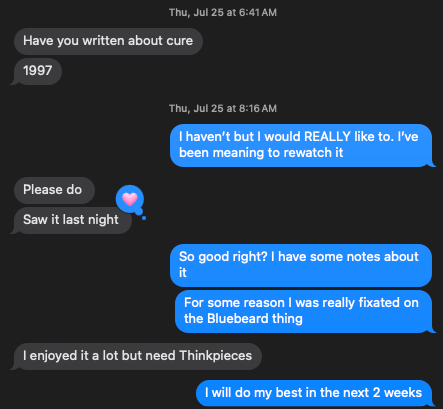

Neichelle died from cancer, a glioblastoma. The life expectancy after such a diagnosis is twelve months, and this particular cancer has a five year survival rate of less than 10%. This shit will kill you. In Cure (1997), Fumie (Anna Nakagawa) says in the film’s opening scene, “I know how the story ends.”

That line seems to me to capture the inevitable outcomes set in motion by the film’s first moments. It is the quotation I used in my title for an unwritten academic paper on Cure, one among many titles I keep in my back pocket about a wide variety of films and novels. But it takes on a new meaning when someone has a terminal illness. The ending of the story of a glioblastoma is already written. Fumie and the film’s villain, Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara), suffer from seemingly disparate ailments that compromise their memory. I can only imagine what a grip this film could have on a person who knows the likely outcome for them is the same neurological failing.

I visited Neichelle in the beginning of February. All things considered, it was a nice visit. Even then, as she seemed to have as firm a grip as ever on her long term recall, her short term memory was failing. We texted before and after the visit, but nothing really got across the sense of her forgetting as much as sitting across from her. I wondered if the text messages were not, in part, some kind of prosthesis, following the threads from our earlier conversations into the later ones.

There is the story of the glioblastoma, a statistically improbable fatal cancer, that is inextricably connected to both Neichelle and the film Cure for me now. Fortunately, that is not the sum of Neichelle’s story. She was loved by a ridiculous number of people who crowded her living room in the weeks and months leading up to her death. This profound outpouring of sentiment wasn’t unusual. I could imagine these vast gatherings of friends, orchestrated by her, that I had the privilege of being a part of many times.

She was an avid consumer of fast food, something we shared as a passion. She loved the film Turbo (2013), a fanatic for the film from its release date. She organized group film viewings (Ape Friday), Animal Crossing (2020) discord servers, and attended a ridiculous number of shows she wouldn’t have otherwise crossed the street for just to hang out with her friends. Her impact on my life is huge, the architect of friendships between me and others I have come to treasure.

I rely on writing and thinking to process my own grief, which should be obvious. Tyler Clapp, my dad, Neichelle, they’ve all gotten much less than their due from me. But when I write stuff like this I never read it back, just give it in the spirit of someone who thinks Mrs Cadwallader saying Casaubon’s blood “was all semicolons and parentheses” is a compliment. And I hope if I leave blood on the page in the form of these marks, and you look at it with a memory of Neichelle, it makes the shape of a person.