Issue #371: How Many Lacanians Does It Take to Plug in an HDMI Cable?

Mobile Suit Gundam: Char’s Counterattack (1988) is one of my favorite movies of all time. I got really, really lucky this week despite traveling and had the opportunity to see it in a very cool independent theater in Columbus, Ohio.

The movie never loses its luster. But I noticed more acutely on the big screen an undeniable example of the “Double Portrait” shot Bergman borrowed from Heinrich Hoerle in Persona (1960).

Someday I’m sure I’ll write about it more, but I’m so relieved my seeing it worked out.

This week, a quick gloss on the fifth LACK conference and some analysis of “The After Hours.” You know, the usual.

Lacanian Conference Scene Report

When LACK (the conference) comes around, it’s my favorite time across a bi- or tri-annual duration. It’s an academic conference with a bit of a DIY ethos, stripping away some of the artifice of traditional conferences in literary studies, critical theory, and psychology. This year, the fifth conference since 2016, was characteristically great. The conference had nearly double the registrants of the previous year with many attendees not presenting papers themselves. I spoke to a lot of “independent scholars” (a mildly insulting euphemism that generally implies “person who wants a teaching job but doesn’t have one”) and Lacanian hobbyists from different walks of life.

Though the LACK conference is by no means average, a career academic can’t escape the fact that conference attendance serves a career obligation. Tenured, tenure track, and even non-TT lecturers are generally expected to attend some amount of conferences every year. They’re also usually supported by their institution — the college where one works will often pay conference registration fees and some portion of travel and lodgings. As someone who has crossed the rubicon into independent scholarship for the first time in my conference-presenting career, I felt the conference to be a welcoming and encouraging environment. And it does mean something for someone to stake their own money on travel and registration fees to come to a conference to present or just watch the panels. They don’t have the career driven imperative. I respect that a lot, and maybe wouldn’t appreciate it as much were I not in a similar position myself.

I have to extend my thanks to the organizers, some of who may be reading, for letting me present yet again. I hope to return next go around, independent scholar or otherwise.

The individual quality of the panels I attended were phenomenal. The curation was excellent and the intellectual contributions of the many academics (and non-academics) presenting and discussing were uniformly impressive. Is it possible that the average quality of conference presentations at LACK is increasing, even with the significantly larger number? Who’s to say.

There were warts, though, through no fault of the organizers. The rooms were hot. Really hot. And there were some issues with tech. A frequent sight before a panel was three or four brilliant psychoanalytic scholars crowded around a lecture hall PC to figure out why whatever device wouldn’t connect to the projector. Something about the view struck me more, as common as this might be at any given conference. Anyone who has been in a college classroom recently knows the capriciousness of those projectors and HDMI cables.

As for the keynote, it had highs and lows. Slavoj Žižek discusses, among a wide range of topics, shame as a repudiation of “buffoonery,” buffoonery in the most horrific political forms imaginable — unapologetic (shameless) brutalization of Palestinian prisoners by Israeli prison guards, among other things. He paraphrases Lacan, who I’ll quote, from The Other Side of Psychoanalysis (1991):

Begin, instead, with the following fact, that the buffoonery is already present. Perhaps, by adding a bit of shame to the mix, who knows, this might keep it in check … I am playing the game of ‘You hear me because I am talking to you.’ Otherwise, there would, rather, be an objection to your hearing what I am saying. And it’s a pity, for at least the younger ones among you have for a fair while now also been capable of saying it without me. You lack for that, precisely, a bit of shame. (182)

In the seminar, Lacan goes on to discuss shame’s function in psychoanalysis:

Be a bit serious and you will notice that this shame is justified by the fact that you do not die of shame, that is, by your maintaining with all your force a discourse of the perverted master—which is the university discourse. (182)

Žižek picks up this thread in his talk, relating shame to the function of psychoanalysis and de-sublimation. He says (from my notes on the talk, so subject to error):

The permissiveness of perversion ends up in a self-destructive deadlock which gives birth to a call for a new master. And as the ongoing wave of new populism demonstrated, the new master’s shamelessness by far exceeds the shamelessness of the old leftist protestors … Shame is not a defense against too much desire, it is a defense of desire.

To this point, repression is the necessary corollary for Žižek. He suggests to defend desire is also to repress less. This is counterintuitive when considering the social value of shame, but one need only examine the psychoanalytic structure of perversion, and Hegel’s (re-canonicalized) lord-bondsman dialectic to understand the demand for the master from the position of the subject delimited by permissiveness.

It is a shame, then, that Žižek’s most salient theoretical commentary of the evening did not precede his very presence in the room. Shortly after sitting down, he was bombarded with requests for asinine photos. And I imagine the enormous line to speak with him after the talk also involved requests for selfies. I wouldn’t know, I was out of there quick. “You lack for that, precisely, a bit of shame.”

Anyway, I had an amazing time. Especially because of the selfies — they give me something to lash out at and satiate my own desire. I will provide a more detailed analysis of the particular papers I enjoyed next week. But I have to shout out my personal hall of fame: Jared Pence, Rosie Overell, Clint Burnham, Tamas Nagypal, and Chapman Matis for hanging out hard all weekend.

“I just got brain surgery in my basement”: Severance Seeking Balance in “The After Hours”

Cliffhangers for All Seasons

In some ways, “The After Hours” is every bit the perfunctory pre-finale episode that tells the audience a lot and moves the pieces into place before the plot takes its last turns for the next two years or so. In the accompanying episode of The Severance Podcast with Ben Stiller & Adam Scott (2025), Stiller and Scott talk about the logic behind cliffhangers [emphasis added]:

Stiller: I think it’s a blast … It’s a totally different experience watching the cliffhangers when the show is playing once a week than when it’s binged.

Scott: When it’s binged, there’s no real point to a cliffhanger, is there?

Stiller: Except to get people to watch the next episode … No, you’re right. That’s what cliffhangers are … the word cliffhanger is, I’m just guessing, is somebody hanging off a cliff in like an old serial Western, probably …

Scott: They want everybody to come back and pay to watch the next one a week later

Stiller: This is the most obvious conversation

This conversation reveals Stiller’s understanding of how to craft serial television. He has no compunction about utilizing the cliffhanger for its most “obvious” and self-interested purpose, to get his audience to return for the next episode. We can expect, as the logic of Severance (2022) has been so far, that the conclusion of season two will also entail its own cliffhanger(s) to motivate the audience to return for the third season.

While “The After Hours” is easily my least favorite episode of the season, it does a lot to stand out from the pack of these kinds of episodes. Severance’s structure isn’t unique, nor does it abstain from using pulpy narrative conventions. It does, however, use these conventions about as effectively as one possibly could. This episode is full of plot revelations and events that might have, in a lesser show, been conveyed in decontextualized expository dialogue. Severance generally shows, not tells, and while “The After Hours” tells more than usual, it seems to show everything it can.

Reading a Show’s Patterns

I’m not in the business of making plot predictions, but I can say if audiences want to avoid the kind of spectacular disappointment they experienced with, say, True Detective (2014) season one, they should be introduced to Rivera’s Theory of Television Criticism.

A show reveals, nearly always, how it will end by what comes before. I don’t mean in the sense of plot, but by the narrative logic that governs how the plot unfolds over the course of the show. In the case of True Detective, audiences expected detailed plot revelations in a show that was rarely concerned with the mystery the Cohle (Matthew McConaughey) and Hart (Woody Harrelson) were trying to solve. Why would a show that rarely set up the specificities of the crime as the engine for the show’s momentum suddenly reveal a detailed conspiracy at its conclusion?

Applying this theory to Severance, the show structures itself around revelations that produce more mystery. The season two finale will follow this pattern. Season one concluded with revelations to questions the audience asked and questions they didn’t. It revealed Gemma (Dichen Lachman) was alive and Helly R (Britt Lower) was, in fact, Helena Eagan. But these also opened the door to even greater and more compelling mysteries. In season two, there will be a few answers to questions the audience has, a few answers to questions they didn’t think to ask, and a new hook that will lead into a subsequent season.

The Craft of Writing in Severance

As a final non-hermeneutic digression, I want to address the critique of “The After Hours” that it is written poorly because Mark (Adam Scott) and Devon (Jen Tullock) are insufficiently motivated to cooperate with Cobel (Patricia Arquette) and yet they do so anyway. Why the series is unfolding this way has nothing to do with psychological realism or verisimilitude, two tremendously overrated elements of fiction, and everything to do with a very common narrative problem. As a writer, how do you deal with a show’s central characters’ not knowing a major plot element that was revealed to the audience? Sometimes this paradigm, the audience knowing something the characters don’t, can be in service of dramatic irony. But, more often than not, it is an inconvenience that puts writers in a tough situation.

As far as Mark and Devon working with Cobel, I would argue this is written very well for the purposes of keeping the show moving — something I think is generally more important than strict psychological realism. Even if Devon and Mark have no reason to trust Cobel, the audience does. We already know why she would help them. She is the disgruntled and discredited creator of the severance procedure itself, with roots in the town turned into a shell of its former self through Lumon’s exploitation. We just learned all of that seven days ago. It would be unconscionably obnoxious for Cobel to repeat that information the audience just learned one more time for the benefit of Devon and Mark so their behavior seems more “realistic.” It’s not to say that I think it’s great when verisimilitude gets a little strained like this, but the alternative is much worse than how they approached it.

We can compare this to the identical narrative situation arising with Helly R at the beginning of the season. The audience knows her true identity, but Mark S, Irving B (John Turturro), and Dylan G (Zach Cherry) don’t. Since there was more time in the season to work with that disparity in knowledge, Dan Erickson and the writing team were able to connect it to a new mystery: is Helly R who she says she is or is she Helena impersonating Helly? Through the audience’s suspicions, and Irving’s suspicions within the text, the show can reveal Helly’s true identity to the characters who don’t know it without woeful repetition and exposition. However, with only three episodes left in the season, an approach like this isn’t an option.

Jumping the Shark and Jumping into the Pool

I think the narrative structure and writing techniques Severance uses are marvelous and worthy of study, which is why I end up writing these kind of analyses. But really I want to talk about what I found thought provoking in the symbolic logic of the episode, not the narrative logic. And that begins with Helena in a pool.

Returning to the space of her near-death experience at the hands of Irving B, the backlit shot of Helena floating in the pool unmistakably evokes her attempted drowning in “Woe’s Hollow,” among other things.

In Severance, water is a threshold. Most obviously, it separates life and death. It is also that within which things are subdivided, such as the case with Mark’s beta fish. And it obscures, as with Milchick’s (Tramell Tillman) iceberg painting.

Helena is flirting with death, seeking to change her relation to it. She is, of course, dealing with another kind of “little death,” the subordination of her consciousness to her severed innie. The liveliness of death has been a major theme this season, especially with the treatment of dead bodies and the possibility of life after death. Alenka Zupančič, in her treatment of Antigone1, writes:

So a first—albeit insufficient—answer would be because, as speaking beings, we have a way of saying death, of talking about it, of thinking it, of establishing a relationship to it. It is not obvious to be able to say death—I do not mean the word “death” but what it implies, what it is. How do you say death? That is an interesting paradox: to be able to say death, you have to bring death to life; you have to make it part of life, give it a symbolic existence to which you can relate; you have to resurrect death from death, so to speak. To say death, you have to make it “symbolically alive,” alive in the symbolic. (Let Them Rot 25-26)

Here, Zupančič refers to the symbolic practices around death regarding burial rites and mourning rituals. But I extend it to the possibility of bringing death to life through the encounter with that which might bring one closer to it — water — or subverting, supplanting, redefining it through whatever science fiction contrivance Severance might reveal.

“I’ll Watch”

This is the beginning of a disquieting observation of Helena’s morning routine. After swimming, she eats a hard-boiled egg under the observation of her father in an extraordinarily bizarre sequence.

She divides the egg into six parts, then cuts into it in a sort of consumptive vivisection.

One might read the egg as related to fertility, a major motif for the episode with the “birthing cabin,” or the constant division of the subject. In the post-show “Inside the Episode,” Lower says of her performance in “The After Hours,” “in so much as my outie character is an antagonist to the innie, I think it goes both ways. It’s such a human thing to be at odds with oneself2.” That opposition requires, implicitly, a division. Severance’s most insistent insight is that the human subject can be infinitely subdivided, though not without a cost.

And this division of subjectivity falls short of dividing the thing that makes the subject cohere, the essence of humanity that transforms one from nothing to something. It is the thing that, it seems to me, Lumon wants to cure with their “cure for mankind.” Erickson, in the same “Inside the Episode,” says about Helena and her father Jame, “He’s never going to give her that foundational love that we all need in order to be human beings.” Love seems to be a core issue for the show, but my psychoanalytic reading would posit the Freudo-Lacanian drive as that which Lumon wishes to cure. In Kiss Me Deadly’s (1955) treatment of nuclear material, it alludes to the drive as that which “cannot be divided.”

It’s easy to compare Helena to Gabrielle (Gaby Rodgers), seeking to divide that which is impossible to sever.

Helena Eagan Horseshoe Theory

The opposition to oneself that Lower describes also refers to Helena and Helly’s mutual disdain for one another. Helly is repulsed by outies as much as Helena is by innies. She consoles Dylan G after Gretchen (Merritt Wever) says she can’t see him anymore:

She’s not your wife. Because no one would treat someone they love the way she’s treating you. Like all the outies treat us. Like everything is for them.

For a moment, Helly sounds prepared to drum up some insurgent sentiment among the outies following from Mark’s rousing speech to Mammalians Nurturable in “Who Is Alive?” Of course, Helly didn’t hear that speech, Helena did, but we are left with a rising mutual antipathy between the two that complicates the idea of any reunion or reconciliation between outie and innie. Imagine what the consequences might be of Helena’s reintegration.

“A most prosaic, ordinary, run-of-the-mill errand”

This antagonism also draws on The Twilight Zone (1959) episode from which this episode gets its name. In that “The After Hours,” Marsha White (Anne Francis) comes to a department store to buy a golden thimble for her mother. A mysterious elevator operator directs her to a ninth floor. This floor is entirely empty, devoid of merchandise and employees save one, who offers to sell her the golden thimble. White remarks:

Well, you haven’t any merchandise here at all, except the thimble, except the very thing I needed … I come up on a floor that hasn’t a single thing except what I’m looking for.

After buying the thimble, she finds it’s scratched, “and it’s dented too … it looks as if somebody stepped on it.” In her attempt to return the thimble, she is informed there is no ninth floor. Finally, after falling asleep in the department store and being locked in after hours3, she’s able to return to the ninth floor and discovers that she is in fact a department store mannequin come to life to live among humans, “the outsiders.” With a touch of the Pygmalion myth, the episode ends with Marsha rejoining the indentured mannequins after exceeding her allotted time in the outside world. Another mannequin was waiting her turn to depart for her scheduled one month human sabbatical.

That Severance draws from the episode so heavily is no surprise, they are deeply connected. Helly’s own rising class consciousness ties to the interesting class positioning in The Twilight Zone episode. The department store itself buttresses the space of the domestic and wage labor, with wives fulfilling an unpaid duty while shopping and women working in the labor market as salespeople. The mannequins themselves are trapped, like severed innies, unable to escape the department store or receive renumeration for their labor.

There is also a rich gloss of demand, desire, and drive in Marsha’s relationship to the gold thimble. She finds what she asks for, but realizes it has an excess — the dents and scratches. These are the marks of an endlessly circulating, metonymic desire that is impossible to satisfy.

“I mean, work is just work, right?”

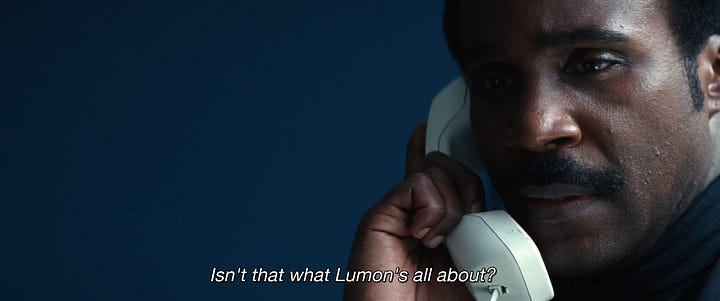

Mark’s call with Milchick is perhaps the deepest connection to The Twilight Zone episode, Mark in the role of Marsha, a mannequin who has overstayed his welcome in the world of “the outsiders.”

His pledge to return is not in good faith, however. He gives his word honestly, he’ll be back to work tomorrow, but not to conclude his work on Cold Harbor. He’ll wreak havoc, I’m sure. But the word is crucial here, Mark is close to "monosyllabic in his simple account of why he needed the day off, and he emphasizes the intractable bulwark that separates the life of life and the socially imposed exigency of wage labor. His words are “very specific language,” using the rigidity of Lumon’s framework and the seriousness with which they take the word against them.

Paper Suicide

Equally important, it seems, are the words written on a page as Dylan G effectively signs his own death warrant in his anguish over the rejection from Gretchen.

That which is written on a page, or in official record, imposes an impassable limit. We can read this into Burt’s (Christopher Walken) parting with Irving, too: “this line goes as far as you can go.” He’s talking about a train that goes to the end of the line, but it is also true that there is a line at the limit of “as far as you can go” that can’t be crossed. That line is the line of the signifier, that which eludes Dylan as he proposes to “Gretchen G,” ignorant of their shared last name: George.

These signifiers and the limits they impose elide the complex and interconnected lines of love and filiation, between innies, outies, across consciousnesses, all those sort of bizarre love arrangements we have seen in this text. Just as was the case with Irving in “Hello, Ms. Cobel,” Dylan can’t see the ties that bind him and can only see that from which he’s been cut off.

The Part and the (W)hole

A relational connection that is below the register of official social life requires “material sacrifice” to maintain. But such a connection also makes impossible ad hoc replacement, reconfiguration, or substitution. This brings us back to that idea of the drive, that human something that can’t be excised or replaced. Helly’s taunt to Milchick, that Lumon “replace[s] one part with another,” is highly suggestive of the philosophical underpinning for the corporation’s plan. They seek to erase anything that can’t be replaced, creating a form of subjectivity of which every aspect is fungible. Humans, like mannequins, who can have their parts painlessly replaced.

Weekly Reading List

The conference left me with a bunch of stuff to read but I haven’t actually read it yet, so I can’t recommend it. You can listen to these albums instead.

Until next time.

Thanks to Jared Pence for pointing me to this text over the weekend.

Erin noted to me in a comment while editing, “what also struck me was the act of swimming (great physical activity) and restrictive eating, when she must be starving/lacking calories.” Couldn’t figure out how to work it into the piece but I thought it was a great point.

The season one episode of Are You Afraid of the Dark? (1990), “The Tale of the Pinball Wizard,” also adapts this premise.