Issue #376: The U.S. Constitution Isn't All It's Cracked Up to Be

Everything is lining up for a great NBA post-season. It’s nice out in Boston. My TV on my (fully enclosed) porch survived the winter. I have been firmly seated in a camping rocking chair as close to outside as I can be.

The games so far have been mostly good. Some games were not competitive. But Game 1 of Nuggets vs. Clippers was an all timer. Knicks vs. Pistons started strong and promises to have more exciting games. If Dame comes back for the Bucks today, I’m going to have to find a way to catch their matchup against the Pacers that has been relegated to NBA TV. And then there’s the Celtics. Fifteen wins away from their 19th franchise championship. Here we go.

Independent Film Festival Boston begins this week, with its first screenings on Wednesday (4/23). It’s a great event for the city and there are tons of awesome screenings. This year, I am hitting fewer than I would like. These three:

April 27th @ 3:30 PM Brattle Theater — Happyend

April 27th @ 7:30 PM Somerville Theater — 40 Acres

April 28th @ 7:00 PM Somerville Theater — Friendship

I also have a test screening for a film due out in August that I can’t talk about on the 23rd and am going to see The Shrouds (2025) on the 24th. And there’s the aforementioned NBA Playoffs. Not exactly a light week for moving pictures, broadly construed.

With all that out of the way, this week’s newsletter is about the most depressing topic imaginable: civil rights violations in the current U.S. political climate.

Post-Enlightenment Morality and Contemporary Deportation

One only has a right if they can assert it. We, in the United States, are in a dire social environment that proves such a point. Take, for instance, the deportation of Kilmar Armando Abrego Garcia, deported to El Salvador based on a “clerical error,” now in a maximum security prison with the ostensible purpose of holding terrorists. These’s no indication of any trial to determine his supposed status as a terrorist or gang member.

Or consider Juan Carlos Lopez-Gomez, a U.S. citizen, imprisoned on the basis of entering Florida as an “unauthorized alien,” according to the law, despite his being a citizen. Thankfully, he only spent one night in the Leon County Jail, a facility less than eight miles from my childhood home.

We are reaping civil and human rights violations that were sown (and also reaped… rights violations are a resilient and invasive crop) as early as World War II, when Japanese-American U.S. citizens were imprisoned in internment camps without due process. But, certainly, the clearest through-line from then to now is the so-called war on terror, during which the government authorized all sorts of exceptions to civil rights and due process.

In the United States, the right to due process is supposedly guaranteed by the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. The Fourteenth is particularly relevant here:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

While the Fourteenth Amendment is specific about what rights should be afforded to citizens, it is also unambiguous in affording due process to any person. Clearly, constitutional rights are not all they have cracked up to be.

“there are no such rights, and belief in them is one with belief in witches and in unicorns.”

Incidentally, after talking extensively about utilitarianism and deontology last week, I want to take up another moral philosopher in this concrete political context: Alasdair MacIntyre. In After Virtue (1981), MacIntyre makes an audacious critique of post-Enlightenment moral theory, “Suppose that the arguments of Kierkegaard, Kant, Diderot, Hume, Smith and the like fail because of certain shared characteristics deriving from their highly specific shared historical background” (51). He goes on to suggest this is exactly the case, that these wide range of moral philosophers fail in their project because of a shared commitment to the idea of human nature. None of these philosophers, following MacIntyre’s view, understand the historical and social contingencies of moral structures, nor has philosophy up to this point recognized this network of thinkers as entrenched in the same kind of historical and social contingencies. MacIntyre writes:

At the same time as they agree largely on the character of morality, they agree also upon what a rational justification of morality would have to be. Its key premises would characterize some feature or features of human nature; and the rules of morality would then be explained and justified as being those rules which a being possessing just such a human nature could be expected to accept …

for Kant the relevant feature of human nature is the universal and categorical character of certain rules of reason. (Kant of course denies that morality is ‘based on human nature’, but what he means by ‘human nature’ is merely the physiological non-rational side of man.) …

Thus all these writers share in the project of constructing valid arguments which will move from premises concerning human nature as they understand it to be to conclusions about the authority of moral rules and precepts. I want to argue that any project of this form was bound to fail, because of an ineradicable discrepancy between their shared conception of moral rules and precepts on the one hand and what was shared—despite much larger divergences—in their conception of human nature on the other. Both conceptions have a history and their relationship can only be made intelligible in the light of that history. (51-52)

There is an extreme condemnation here from MacIntyre, then. In short, any moral system is bound to fail to the extent that it relies on some essential human nature as its guarantor. MacIntyre sees this formula as originating in Nicomachean Ethics, “Within that teleological scheme there is a fundamental contrast between man-as-he-happens-to-be and man-as-he-could-be-if-he-realized-his-essential-nature” (52). MacIntyre goes on, “Ethics therefore in this view presupposes some account of a potentiality and act, some account of the essence of man as a rational animal and above all some account of the human telos” (52). These assumptions that underwrite a wide range of ethical projects are mistaken, and thus doom the ethical system that spawns from these erroneous assumptions. MacIntyre uses this as the foundation for a dismissal of rights as such:

It would of course be a little odd that there should be such rights attaching to human beings simply qua human beings in light of the fact, which I alluded to in my discussion of Gewirth's argument, that there is no expression in any ancient or medieval language correctly translated by our expression 'a right' until near the close of the middle ages: the concept lacks any means of expression in Hebrew, Greek, Latin or Arabic, classical or medieval, before about 1400, let alone in Old English, or in Japanese even as late as the mid-nineteenth century. From this it does not of course follow that there are no natural or human rights; it only follows that no one could have known that there were. And this at least raises certain questions. But we do not need to be distracted into answering them, for the truth is plain: there are no such rights, and belief in them is one with belief in witches and in unicorns. (69)

If the argument that rights are a feature of ontology is supported by the same source as these ethical theories, human nature, it is equally fallible, especially as they are divorced from a given historical and social context. They are illusory as universal truths, which, in my view, makes them all the more important to codify in law and culture.

Rights Must Be Defended

I find MacIntyre’s view convincing, but this is not to say that there should be no such articulation of rights by the judiciary. Indeed, the opposite is true. We need powerful social and legal intervention to protect rights given the disjunction between how humans behave and the rights a society should protect. I have an uncharacteristically prescriptive view of what is required to sustain human rights, given the ease with which they are imperiled or done away with. The violation of fundamental human rights must be dealt with in the most punitive and extreme terms. The punishment, in all circumstances, should be administered to the individual agent whose action violated another’s rights. Additionally, if this agent was acting on behalf of an agency or organization, that organization should also be equally penalized. Of course, it is often the case that these individuals who violate one’s rights are acting outside of the scope of their official duties or authorized function. If a government or other institution finds repeated examples of the same kind of violation, the organization should be sanctioned regardless of whether or not they allow or prohibit the violation of rights. We might find most United States municipal police departments being sanctioned under this standard. What I am suggesting is far from radical in the context of U.S. legal precedent. Federal fair housing protections have a nearly identical standard, making both the individual agent and company they represent culpable for violations of these protections. Somehow, our current society treats violations of this kind more severely than violations of one’s right to due process. This is no accident. The federal government has created numerous exceptions and loopholes to make this right completely superficial. This has been true, at least, since the onset of the so-called “war on terror.” It just happens to be the case we are seeing the outcomes of these policies to detain and forcefully expatriate immigrants.

Rights must be defended. Without a sufficient structure to defend them, they don’t exist. We have seen, repeatedly, the threat or use of force to circumvent the protection of civil and human rights. In the case of municipal police, who enjoy qualified immunity, they are largely protected from any penalty for infringing upon rights in this manner. I have always found one of my father’s stories about being menaced by a police officer philosophically instructive. If I recall correctly, he was a newly appointed paralegal for Florida’s Department of Labor. Driving to Ocala from Tallahassee to pick up documents for a case, he was stopped by a police officer or sheriff’s deputy. After checking his identification, clearly designating his ethnicity through his name, the officer told him to turn the car around including a vague threat of violence, leave “before you get hurt.” My dad asked “with what authority” the officer was demanding he leave Ocala. The part I’ll never forget is my dad telling me the officer put his hand on his gun, saying “this is my authority.”

This story is hardly unique, and echoes the circumstances of the deportations and detainments we have seen where those with Latino names are targeted. Likewise, the law enforcement agent in my dad’s recollection deferring to his gun, his capacity for violence, as his authority, shows the weakness of the framework of U.S. human and civil rights that has only deteriorated since. Aside from a mutual embrace of violence to adjudicate these matters — which I absolutely denounce — only a more aggressive legislative defense of rights can curb the erosion of their power.

What is at stake in this transformation of rights is nothing short of everything. To deny due process to one person means it is not guaranteed for any person. What we have seen is a systemic denial of due process. I feel we are satisfactorily far from slippery slope catastrophizing. The threat is manifest, and it is a threat to you if you reside in the United States. Whatever flimsy justification is applied for imprisonment without evidence and deportation without legal authority means that any person could be treated in this way if the justification does not require evidence or proof. Abrego Garcia and Lopez-Gomez are not canaries in the coal mine, they’re the dead body of rights choked by carbon monoxide.

The Rebrand: Influencer-Phobia and Horror Film

It takes a lot to stand out in the quickly crowding sub-genre of influencer horror. There are some pretty obvious missteps a movie like this can take. As I argued back in 2021, to make the influencer an object of revulsion and allow the audience to distance themselves from an immanently “hatable” social tendency is one such mistake.

Many films seem to have moved away from this tendency over the past three years. Opus (2025) ends with Ariel Ecton’s (Ayo Edebiri) ascendency to culturally significant author with the same kind of misguided fans as those who worship Alfred Moretti (John Malkovich). Jess Peters (Dani Barker) must choose to subject her friend Kai (Eliana Jones) to the same observation, stalking, and terror she suffered to avoid her own death at the end of Follow Her (2022). The dynamics in the excellent Influencer (2022) are a bit more complicated, but both CW (Cassandra Naud) and Madison (Emily Tennant) are implicated in transforming into something they seem to initially reject. These films show the endless appetite of a market for these kinds of figures and the risk of “becoming what you hate” when ignoring the social factors that motivate people into a certain position. The Rebrand (2025) takes a similar approach, presenting a terrifying villain in Thistle (Nancy Webb) but also showing how easily those who reject her, like Nicole (Naomi Silver-Vézina), might find themselves sufficiently motivated to embrace the influencer lifestyle.

Kaye Adelaide’s film is as thoughtful as any that addresses these topics. But its greatest strengths are more basic. It is tense, exciting, hilarious, and well-acted. Nancy Webb acts in the tradition of Mark Duplass in Creep (2014), but the surface level similarities give way to theoretical underpinnings I find more similar to Spree (2020). Creep is, in many ways, a relic of the kind of film that condemns the influencer as a social outlier. Aaron (Patrick Brice) is incentivized to film Duplass’s Josef because of the financial incentive. While getting paid is part of the story for Naomi, Thistle makes it impossible for Naomi to leave regardless of her acceptance or denial of payment.

It’s not easy to create a truly terrifying villain that also stages an encounter, for the audience, with one’s own worst tendencies. The Rebrand is hugely successful in this regard. It’s a fantastic film, and a compassionate one, that treats the influencer as a symptom of culture rather than an arbitrarily emerging disease. It’s a Paradox Newsletter Oscar winner.

Being the Self You Imagine When the Camera is Off: The Rehearsal, “Gotta Have Fun”

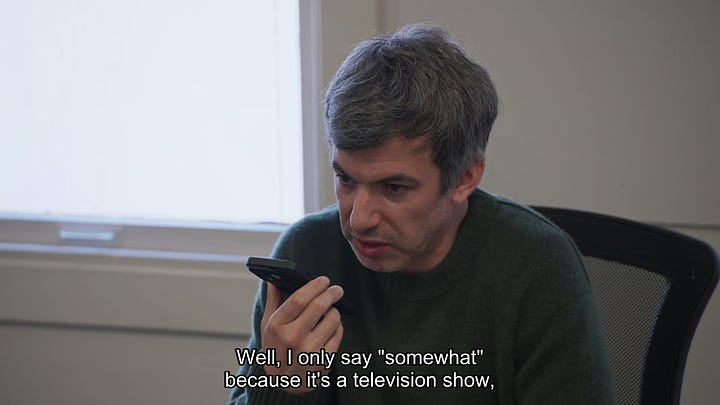

In Alan Sepinwall’s review of The Rehearsal’s (2022) newest season for Rolling Stone, he writes:

In the first episode, asked if The Rehearsal is a documentary, he replies,“I would use that term loosely.” Similarly, it seems fair to use the idea of Fielder being himself on-camera loosely. At minimum, he’s playing an exaggerated version of himself, if not a wholly created character. In the hopes of clarity here, I’ll refer to the person who helps write and produce the show as Fielder, and the guy we see onscreen as Nathan — even though there are occasions where Nathan is more overtly acting as Fielder. See? Not confusing at all.

This extensive author’s note to account for what Sepinwall believes are disparate descriptions of someone named “Fielder,” the producer and creative who supposedly does not appear on camera, and “Nathan,” the caricature Fielder plays, is the most interesting moment in the entire piece. What it reveals about Sepinwall is either he has missed the point of Fielder’s work completely (I make no such unnecessary distinctions between some imposed, interpretive dichotomy) or he is uncomfortable dealing with the ambiguity Fielder’s work requires. My suspicion is the latter. Nathan Fielder’s entire project, across every piece of work, can be summarized relatively simply: performing for an audience is transformative, but we are in a social situation where we are always performing and thus necessarily divided from a fantasmatic version of an authentic self. To simply further, there is no authentic self for the camera to transform. We are always that performing, socially entangled persona, inevitably distorted from the original distortion, a misrecognition that is constitutive of our identity that Jacques Lacan describes in his account of the mirror stage.

Fielder is not a Lacanian, but an artist who demands his audience accept irreconcilable contradiction and ambiguity. Lacan, as a thinker, does the same. Any attempt to cleanly divide Nathan’s supposed personas, to the extent that there are even different personas to disentangle, is misguided at best and misleading at worst. Sepinwall’s interpretive mistake here is even more obvious as he narrates what is “arguably the point of it all,” “Fielder trying to set up the most extreme contrast between the task at hand and what his fictionalized self really cares about.” And yet, the necessity to bracket Fielder’s feelings as belonging to “his fictionalized self” is a great first step to make a bad argument about “the point of it all.” After all, who wouldn’t have some implicit investment in reducing the number of commercial aviation disasters? Only a sadist, sociopath, or aspiring terrorist. It’s not hard to see why this ostensible premise is compelling, or why someone would be invested in making air travel safer.

But saving lives is not the point of it all, nor are the extreme contrasts, despite the latter being the main source of humor. The point of it all is a different contrast, the one between the noble motives of making flying safer and the ignoble motives of making a television show. If there is a difference between the Fielder on-camera and off, they are both subject to this tension. Fielder wouldn’t have anything to offer in the way of creating a solution to this problem without the HBO funding, as he repeatedly emphasizes in the first episode. But what goes unstated is that Fielder’s own initiative in solving the problem would also evaporate without the cameras to watch it. This is equally true for most televised endeavors, particularly those chronicled in non-fiction reality TV or narrativized documentary. One does whatever they’re doing so they have something to film — as distinct from documentary approaches that are covering events that already happened. But even those conventional documentary setups invite a form of “acting out” that Fielder is so skilled at capturing. With any seemingly significant event, the participants may, and probably do, consider getting on the news or being contacted by a documentarian.

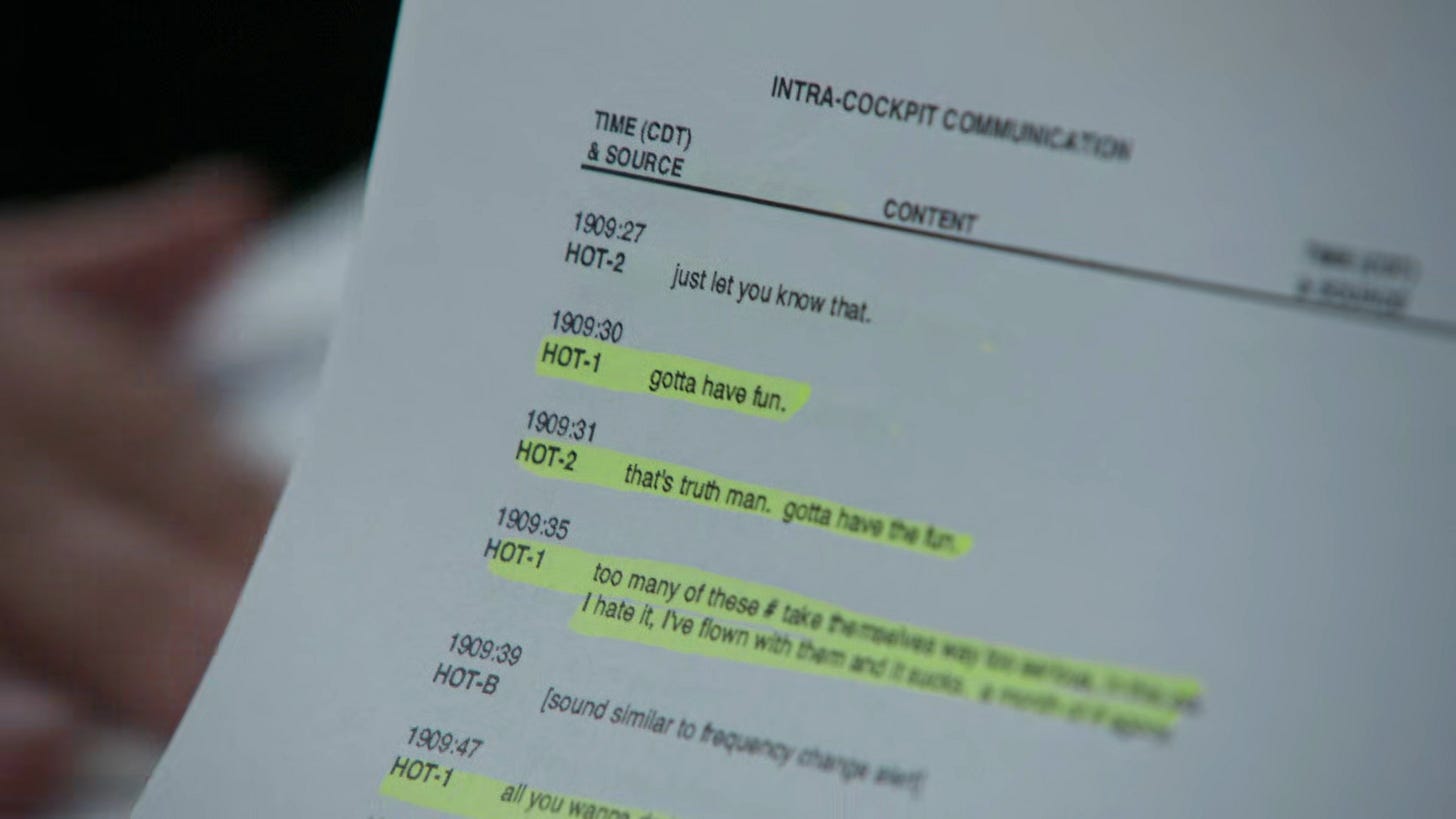

For The Rehearsal season two and “Gotta Have Fun,” this is all table stakes. At this point in his career, Fielder takes for granted that the observed human behaves “differently,” but defining the substance of that difference is impossible because the human is always observed. We hold on to an ideal, a fantasy, of some unobserved essential human conduct supported by a structural analogy to the observer effect in physics, but that effect’s very paradox shows exactly how fantasmatic an unobserved behavioral state is for humans. Fielder repeatedly emphasizes this point, but no longer seems to argue for it. He mentions “The Fielder Method” in passing, an acting style he advances in the first season that involves extensive observation of a specific person. Fielder is bizarrely situated in the front of his mock airplanes, between the screen that represents the view from the cockpit, further exaggerating the falsity of the situation in which he puts his pretend pilots.

“Gotta Have Fun” treads some new ground for Fielder, dealing with epistemology and anxiety. He wrestles with his position as a comedian, analogizing himself to a clown, and wonders how from his position he can produce real knowledge — some ammunition for Sepinwall’s reading about these kinds of contrasts as the season’s main point. He also explores the romantic situation of a co-pilot, Moody, who wrestles with anxious thoughts about his girlfriend, Cindy, leaving him for a customer at her Starbucks job. The structure of Moody’s anxiety is Oedipal. Fielder treats his concern as outrageous, but it turns out to be on the mark as Cindy describes receiving anklets, flowers, and going out for coffee with customers who seem to be hitting on her. Moody brings about what he most fears through his anxiety, as does Oedipus.

It is rewarding to see Fielder advance his range of interests beyond the disjunction between how a human imagines themselves “authentically” and how they behave while observed. Nathan’s own anxiety is about being taken seriously in his view about safer air travel:

Don’t get me wrong, I love being a comedian. But when you lead a life dedicated to making others laugh, in those rare moments when you want to be taken seriously, it can be difficult to overcome the deficit of credibility you’ve created for yourself.

There is a similarity, then, between Fielder and Moody. Nathan Fielder, as a comic, has always been seen as someone with a penchant for seriously incisive social commentary. He, in fact, minimizes his cultural presence in his narration. I imagine Fielder himself may encounter the self-fulfilling prophecy of his anxiety, as he attempts to minimize that uncertainty through the control he grasps for in the repeated rehearsals. But, as he has shown in every season so far, these rehearsals are futile because human behavior is unpredictable. Even as there is some level of certainty that one acts (out) for the camera, what form that will take is impossible to predict. Fielder’s most unquestionable gift is that he can find the figures who, on camera, will act out in the way he hopes. Watching the show, my biggest question is how many co-pilots were considered to serve the role Moody serves in “Gotta Have Fun.” The most seasoned reality TV casting director pales in comparison to Fielder’s preternatural gift for finding those who radiate strangeness when the camera starts rolling.

Weekly Reading List

Joseph Heath’s long running In Due Course blog has found a new home on Substack. This past week, he tackles a contentious idea: “equity” in the colloquial sense. We’re talking boxes “meme”. I don’t even need to post it, you know what I am talking about. Heath’s exploration is very informative, but for my money this is the most important point he makes:

First, the distribution problem presented in the image is zero-sum. There are only three boxes, and so in order to give an extra one to the short kid it is necessary to take one away from the tall guy. Situations like this sometimes arise in real life, but a lot of problems do not have this structure. They involve rather the distribution of (what Rawls called) the benefits and burdens of cooperation – which makes the interaction, by definition, positive-sum. This is important to emphasize, because a lot of people misclassify positive-sum interactions as zero-sum, and so adopt unnecessarily polarizing moral stances.

The idea of resources as zero-sum has plagued moral reasoning in the age of “micro-reparations,” mutual aid, and venmo activism. Instead of understanding the potential of a positive-sum form of collective benefit, there is a strong emotional investment in redistribution that divests something from someone. In other words, it’s not enough for someone to receive a benefit — someone else has to lose something in the exchange, too. This is the punitive logic of contemporary social media leftism.

Incidently, Heath’s detailed account of the thinking about equality in moral philosophy iterates again on what I wrote about utilitarianism last week and answers some of the critiques of MacIntyre in After Virtue. You can get a great overview of utilitarianism, its critics, and its historical trajectory across this bundle of works.

It’s a big week for retro Japanese RPGs with the release of Lunar Remastered Collection (2025). I really enjoyed these two brief documentaries, chronicling the making and localization of both games.

Both videos were included with the North American release of the respective titles.

For “the real hip-hop is over heeeeere” chanters.

Sami Reiss does it again, tackling Trader Joe’s and the green halo.

https://www.espn.com/nba/story/_/id/44704219/inside-end-luka-doncic-era-dallas-mavericks — A deep dive into the disastrous Luka Dončić trade, shedding light on a surprising cause — a shakeup in the Maverick’s health and performance team.

Until next time.

![After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory [Book] After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory [Book]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!f-m9!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F684eb49c-34cc-42df-b907-1cfd74be2345_1705x2560.jpeg)