Issue #385: Orthodox Mysteries, Unorthodox Subjects

There’s a topic I’ve been meaning to get to for about a month now: the Crystal Ballroom’s movie trivia. Hosted by Billy Thegenus and Ian Brownell, it’s once monthly, free, and is accompanied by a level of production that justifies the monthly cadence. It is also a pretty competitive affair. I compete with a team called Dunston Checks In Bruges (get it?) with a name inspired partially by my friend Ronnie. Regular team members are my wife Erin, friend of the letter Tyler, and hopefully-reading-this-newsletter-right-now new friend Bobby. Last month we came in 7th, this month in 5th. I think there are like 30 teams. Trivia championship is within reach.

Honestly, I’m getting carried. But if they do a film noir or Japanese film category… I’ll be racking up the points.

This week, a return to theorizing the anti-social woman of film noir and some writing about one of my favorite literary genres: honkaku.

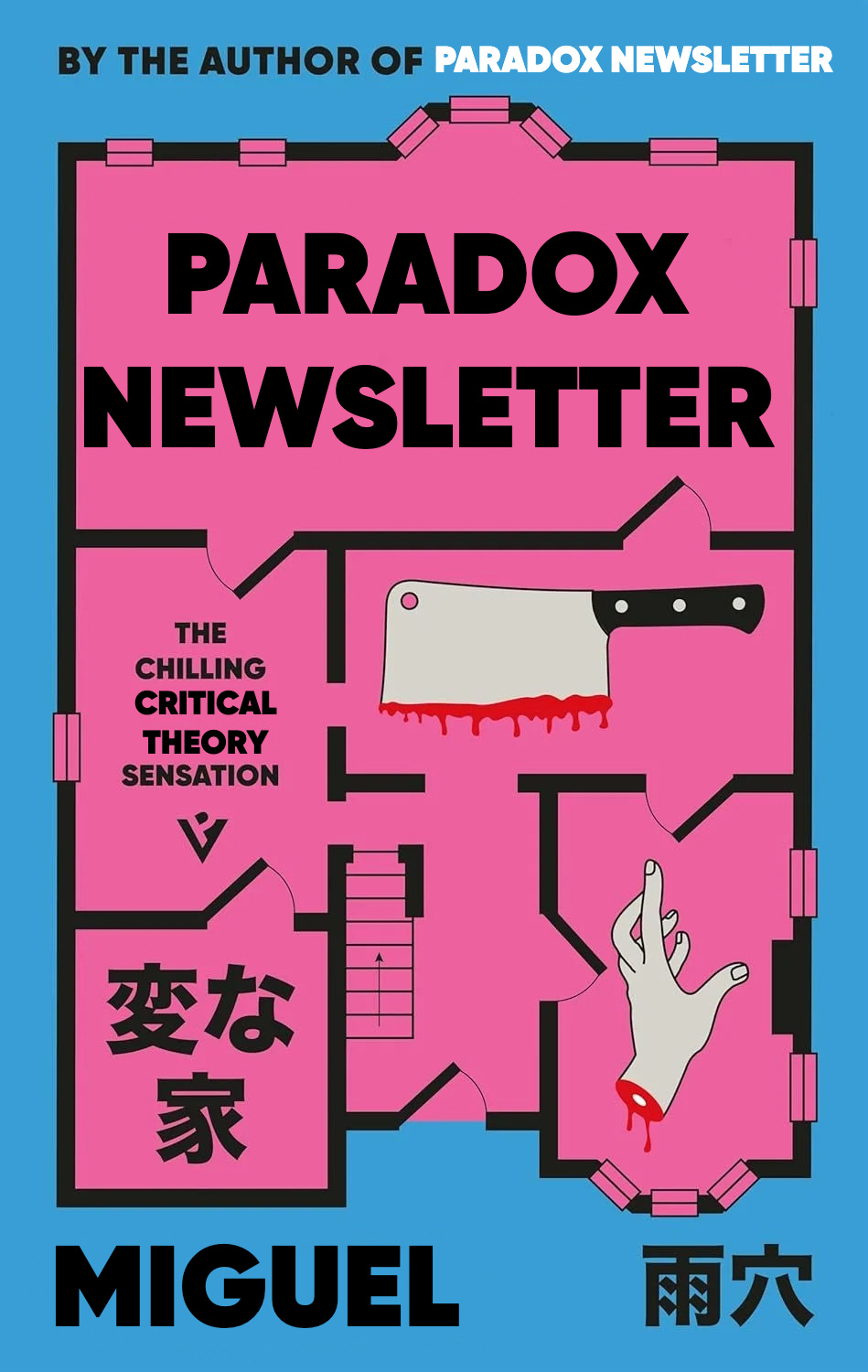

Interpretive Enclosure and Deterministic Hermeneutics in Strange Pictures

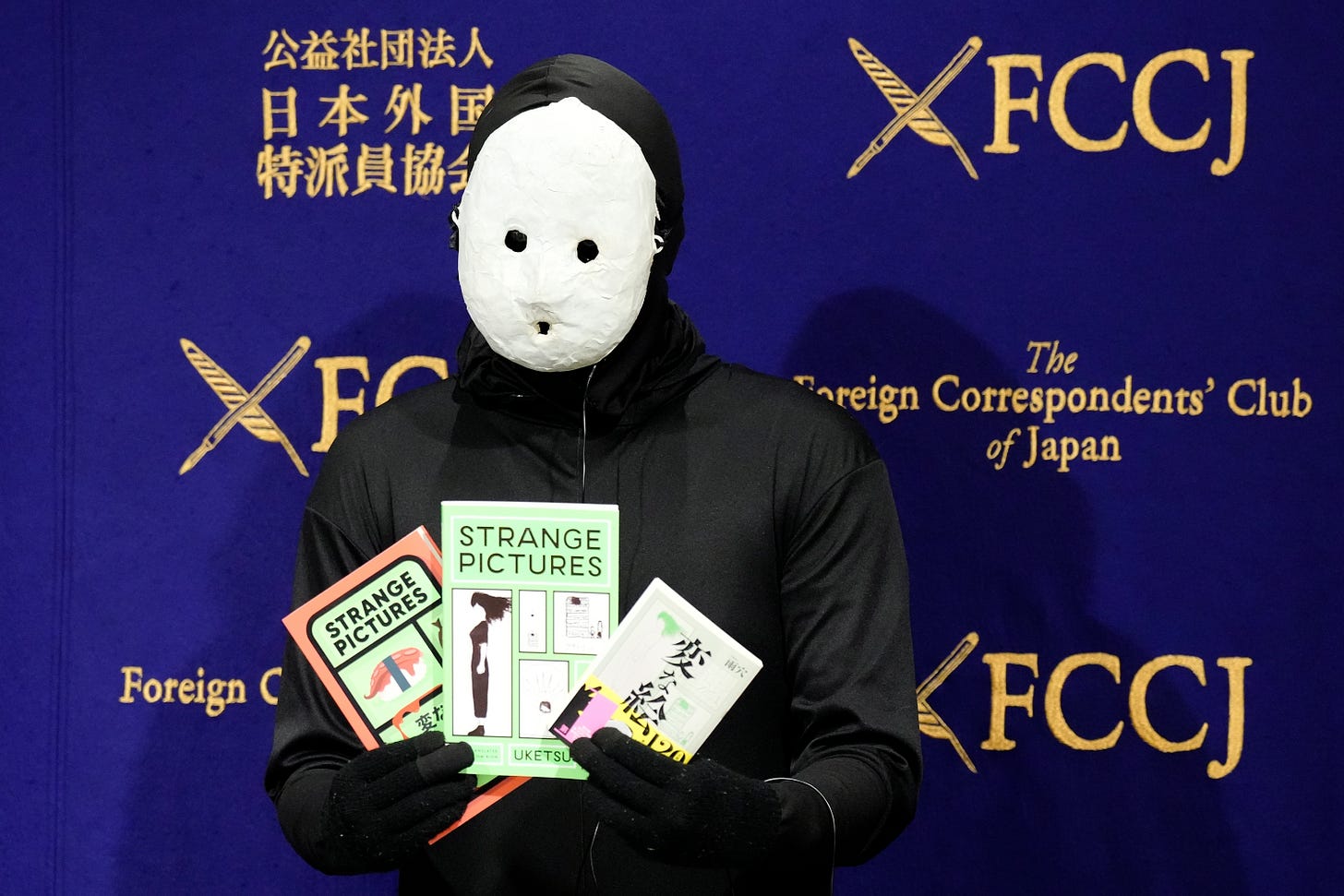

I would not immediately assume that a niche youtube storyteller would write into one of the most storied genres of popular Japanese literature. I was surprised, then, to find that Uketsu’s two novels, Strange Houses (2021) and Strange Pictures (2022) are firmly rooted in the honkaku genre. “Honkaku” translates literally to “orthodox,” Caroline Crampton describing the genre as, “fiendishly clear and complex puzzle scenarios … that can only be solved through logical deduction.” She quotes author Haruto Yoshitame, genre progenitor, who says honkaku stories are “mainly focus[ed] on the process of a criminal investigation and values the entertainment derived from pure logical reasoning.”

I got a lot of funny looks when I presented about honkaku and Soji Shimada’s The Tokyo Zodiac Murders (1981) at the 2018 International Poe and Hawthorne Conference in Kyoto, Japan. One audience member went so far as to ask, bluntly, “why would you ever write about this?” The conclusion I came to as a result of the chilly reception to my paper is that literary studies in Japan hasn’t embraced genre fiction in the same way as the U.S. academy. Indeed, honkaku opposes itself to that which has been assimilated into the canon of properly “literary” texts. In that 2018 paper, I write:

[Honkaku] opposes itself to the psychological thrillers that follow the model of American hard boiled fiction … popular in [1980s Japan] acccording to Shimada himself.

Shimada opted for influences like Poe, Christie, and Conan Doyle, by way of Edogawa Rampo, instead of the hardboiled influences that Akira Kurosawa, Koreyoshi Kurahara, and Toshio Masuda would embrace in their noir films decades earlier. Yukito Ayatsuji, author of The Decagon House Murders (1987) and honkaku revivalist, would name his characters after the most influential authors to the genre: Ellery Queen, John Dickson Carr, Gaston Leroux, Edgar Allan Poe, Agatha Christie, and Baroness Orczy (The Decagon 19).

Understanding that honkaku is a pulpy, maligned genre of Japanese literature helps make sense of why a storyteller primarily using the undignified medium of youtube would gravitate toward it. Like Keigo Higashino’s Malice (1996), Uketsu sets out to add a dimension of psychological depth to his vision of honkaku, characteristic of the shin-honkaku subgenre that is more representative of the genre from the 1980s onward. Similar to The Tokyo Zodiac Murders and the works that would follow it, including Malice, Uketsu’s work tends to embrace the postmodern, metafictional flourishes of shin-honkaku.

The Tokyo Zodiac Murders stages its narrative as a work of literary non-fiction in the plot of the novel, a work that chronicles the events that led to the very writing of the work itself. Malice unfolds across two separate accounts, each point of view confined: one being testimony to the police and the other notes from the investigating detective. Each point of view is limited by the plot’s logic. Osamu Nonoguchi, the character who gives testimony to the police, is positioned as an unreliable narrator to the extent he only wishes to disclose some details to the police but not others.

Strange Houses plays with this same kind of metafictional framing, following an unnamed narrator whose non-fiction book (in the plot’s logic) the audience is reading. It also includes a postscript from one of the characters, who reflects on the actual text of Strange Houses that the reader has just read. Strange Pictures lacks the same kind of fascinating formal hook. In fact, despite Strange Houses preceding Strange Pictures, Strange Houses feels like the much more complete and polished novel. Strange Pictures, by contrast, lacks the depth and sophistication of its predecessor.

Uketsu’s novels have a sustained interest in the relationship between hermeneutic, interpretive reading and the intellectual exercise of solving a mystery with an unambiguous solution. Strange Pictures, though, seems to somewhat clumsily conflate the two. The novel begins with a psychoanalytic interpretation of a child’s drawing, cleverly named “Little A” as an allusion to Lacan’s objet petit a:

After looking at this picture, I concluded that Little A had a strong chance at rehabilitation. Can you see why? Look again at the tree. This time, look past the branches, and focus on the trunk. There is a little bird living in a hollow there. People who draw pictures like this display a desire to protect, and a tendency towards strong nurturing love. It expresses the desire to defend the weak, and to create a safe haven for them to live in. (7)

The novel is bookended by this analyst’s musings, returning to one of the titular ‘strange pictures’ with a different interpretation of its meaning in light of what happens between these bookends. But each other ‘strange picture,’ all of them represented in detail within the novel, is not a question of interpretation. They are visual puzzles, optical illusions, and hidden communiqués with a determinative meaning. Strange Pictures doesn’t have any inclination to disentangle these two kinds of very different intellectual enterprises, leaving the audience to wonder if Uketsu even recognizes this crucial distinction.

A weakness, in my view, of Strange Pictures is its aversion to ambiguity. Every aspect of the novel’s mystery is explained in painstaking detail. Uketsu reduces the opportunity for interpretation by treating that which could be interpreted as plot material to be explicitly accounted for. This is very different from the approach Uketsu takes in Strange Houses, which leaves much of its plot ambiguous and open to reader interpretation. Strange Houses substitutes the illustrations of Strange Pictures for floor plans, each of which have some unusual design element. Kurihara, a draughtsman, endeavors to account for these unusual design elements. As he learns more, however, his view understandably changes. He even refers to his hypotheses about the houses as readings, “Thinking of things that way changes my reading of this other house” (83).

Uketsu’s thematic concerns could follow from Oedipus Rex (429 BC), fitting if we read Oedipus as the ur-detective and Sophocles’s play as the first ever work of mystery fiction, as I claim in my 2018 paper. He is preoccupied with the relationship between mothers and sons, particularly in Strange Pictures which explores the destructive potential of a maternal position. Strange Houses also treats vexed maternal and paternal figures, examining a large, aristocratic Japanese family with incestuous origins.

Even considering the relative shortcomings of Strange Pictures, both of Uketsu’s novels available in English are riveting elaborations of the honkaku genre. These texts, particularly those that make it onto the shelves of U.S. bookstores, are often more than they appear. Even as authors, Uketsu included, prioritize “fair-play” mysteries that make themselves available to be solved by the reader before the solution is revealed, there is opportunity to synthesize form and content to pose substantial intellectual questions and explore different thematic considerations. While Strange Pictures brings the reader into a world where mystery exists only to be dissolved by rigorous intellect, Strange Houses is a novel that impresses upon its audience the limit of what is knowable. I prefer the worldview of the latter to the former, but the works are also fascinating because of the ways they diverge.

Uketsu’s work is a great entry point into a long archive of page-turning honkaku mysteries.

Society Run “With a piece of rubber hose” in John Cromwell’s Caged

All of George Jackson’s writing, in one way or another, has something to do with prison. It would be more accurate to say he writes about the carceral state, but I would like to avoid any euphemism that comes with this added theoretical detail. Jackson was incarcerated for over a third of his life, in California Youth Authority correctional facilities, San Quentin, and Soledad Prison. In Blood in My Eye (1972) Jackson writes:

The purpose of the chief repressive institutions within the totalitarian capitalist state is clearly to discourage and prohibit certain activity, and the prohibitions are aimed at very distinctly defined sectors of the class- and race-sensitized society. The ultimate expression of law is not order—it’s prison. (99)

Jackson’s recollections and analysis make explicit the relationship between repression and incarceration. Prison is not simply a judiciary function, but a mechanism to maintain state power and target those who might represent a threat to the status quo.

Prison also represents a significant threat to one’s subjective formation. In The Autobiography (1965), Malcolm X writes:

I can’t remember any of my prison numbers. That seems surprising, even after the dozen years since I have been out of prison. Because your number in prison became part of you. You never heard your name, only your number. On all of your clothing, every item, was your number, stenciled. It grew stenciled on your brain. (175)

X emphasizes the punitive mental function that dissociates the individual from the mark of their identity and reduces them to a number necessarily devoid of all of the things a name provides: historical context, distinction from the other, familial and social ties.

It’s ironic, then, for both Jackson and X that their political consciousness arises in the course of their imprisonment. The carceral system lays bare many of these mechanisms. And a common experience between the two is the description of free time to read and think. Jackson concludes:

In the early service of the people there must be totally committed, professional revolutionaries who understand that all human life is meaningless if it is not accompanied by the controls that determine that quality. I am one of these. My life has absolutely no value. I’m the man under the hatches, the desperate one. We will make the revolution. Nothing can stop us, we are not intimidated by the specter of repression—we’re already repressed. (33)

The scope of the repression prison imposes is what Jackson would go on to categorize as a “serious tactical mistake … which radicalizes the population against [the Establishment]” (53), quoting in turn John Gerassi’s The Coming of the New International (1970).

Because prison serves these multiplicitous functions of political enforcement and severely harms those who are incarcerated, one might object to the tradition of “women in prison” films that include the descriptively named Girls in Prison (1956), Women in Cages (1971), and Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion (1972). These films are pulpy, melodramatic, and sometimes pornographic. It takes some very adept, and perhaps optimistic, critical faculties to extract the subversive character from these films that also appear to indulge perverse masculine fantasies.

But before these films, there have also been serious treatment of women’s prisons with a dramatic — not melodramatic — character. Among these films are Caged (1950) and Victims of Sin (1951). Caged is particularly relevant to Jackson and X’s insights, and in fact anticipates them. Following my brief discussion of the film last week, it is a film in which a woman is radicalized as a criminal agent because of her imprisonment. A person who might have otherwise been a “well-adjusted” participant in the pervading ideology is forced to reject it because of the sadism of individual prison employees, like Evelyn Harper (Hope Emerson), and the system itself.

The incarcerated protagonist Marie Allen (Eleanor Parker) is “sent upstate” only as an accessory to a crime committed by her husband. Her imperiled class position and estrangement from her mother results in her being denied parole despite every piece of evidence suggesting Allen stringently objects to criminal activity. It is only after this denial that she begins to undermine the prison’s draconian rules and question the authority that has subjected her to egregious harm.

Caged is complex in its relation to the status quo. Different characters either explicitly or implicitly endorse or subvert it. Warden Ruth Benton (Agnes Moorehead) is benevolent in contrast to the brutal matron Harper.

But Benton is unsuccessful in her attempts to change prison policies and fire the politically appointed Harper. Reformism falls short here, suggesting some intractable impossibility. Jackson writes:

To the slave, revolution is an imperative, a love-inspired, conscious act of desperation. It’s aggressive. It isn’t “cool” or cautious. It’s bold, audacious, violent, an expression of icy, disdainful hatred! It can hardly be any other way without raising a fundamental contradiction … If revolution is tied to dependence on the inscrutabilities of “long-range policies,” it cannot be made relevant to the person who expects to die tomorrow. (9-10)

Jackon rejects the notion of reform masking as revolution because it raises “a fundamental contradiction.” But there is another contradiction in Jackson’s revolutionary formula, between “disdainful hatred” and that which is “love-inspired” that Caged explores.

In this case, it is a question of maternal love. Allen gives birth to a child while in prison, but is forced to give the child up as a result of her familial estrangement. In a repetition of her aspiration to motherhood, she later finds a stray cat to care for.

The discovery and confiscation of the cat results in a ‘riot,’ albeit one focused on the harm of property rather than persons. This is a still a horrific transgression under a regime of “[b]ourgeois law [that] protects property relations and not social relationships” (Jackson 100).

That same social relationship that is unprotected by law makes its return after Allen’s solitary confinement as a consequence for the riot. Harper also shaves Allen’s head, in an attempt to both dehumanize and ungender. Upon Allen’s release from solitary, marched back into her shared cell and showing her compatriots her shaved head for the first time, the prisoners respond with a unified act of rebellion for which they cannot be penalized — slamming the door of their trunk shut as a show of support for Allen.

There is a stark contrast here to the earlier eruption of property violence. Now, the prisoners are unified and expressing solidarity even as they do so in a way to avoid violating the explicit rules of the prison.

Dejected and psychologically tortured, Allen finally accepts the invitation of Elvira Powell (Lee Patrick) to join a shoplifting ring in exchange for Powell arranging Allen’s parole. In Allen’s assent to Powell’s request, she is framed similarly to her protection of the cat.

Positioned in the center-right of the screen, one can immediately see the differences that evince her transformation: the leisurely grip of the mirror, the self-reflexive gaze applying the makeup, and the certainty of what the outcome will be as a result of her association with Powell. Before agreeing to join the crime ring, an older prisoner, Millie (Gertrude W. Hoffmann), insists that a conventional life under patriarchy is preferable to a life of crime:

Wait a year on dead time, but get a legit job slinging hash. Then, get a good guy, have a kid. What I’d give for a sink full of dirty dishes.

Allen has aspired to such a life, free from behind bars. But the machination of the carceral state have made those aspirations impossible at every turn. Indeed, they have discouraged her from “honest living” and implicitly directed her toward crime.

This form of exclusion is also an initiation into another realm of (non-)existence. In light of Jackson’s commentary, one can see the degree to which Allen’s turn to crime — petty or sophisticated — does present some insurgent potential to the degree it rejects the status quo Millie implores her to accept. Though there are social ties that cohere within a criminal network, as in a revolutionary network, these connections are not the sort that assimilate someone into broader social life. This is by virtue of what those who share in these ties aspire to and reject about polite society.

The relationship between Allen and Powell, another symbolically parental one where Powell is in the role of the mother, emphasizes precisely the shortcoming Jackson identifies in how one might leave a prison: isolated. He writes:

The only effective challenge to power is one that is broad enough to make isolation impossible, and intensive enough to cause repression to affect the normal life style of as many members of society as possible. (29)

Because such extreme repression only effects a relatively small segment of society, there are too few people with proverbial skin in the game. Allen’s departure from the prison isolates her from even the solidarity she enjoyed in the momentary support from the other prisoners, slamming down the lids of their storage trunks.

This is the blueprint for the anti-social woman. Not devoid of sociality but in a world that is underground, a woman “under the hatches,” the “sisters under the mink” of Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat (1953). And a world that is particular enough to mark one as excluded from the ‘normal repression’ of social life. The kind of solidarity one might engage in to the end of crime or revolution is at odds with law that both orders society and regulates appropriate forms of enlightened political expression. That which is acceptable in an ideological framework is incapable of overturning that framework.

All of these culminate in the film’s climactic moment, Kitty Stark’s (Betty Garde) killing of matron Harper.

Stark is only capable of such an act because of her profound state of exception, ‘mental instability’ resulting from a month in solitary confinement. Her state of exception, characterized by an inability to socialize that necessarily creates isolation, is what makes her capable of this kind of insurgent killing. At the same time, because the act is isolated, though it may improve the life of the prisoners who no longer have to live under Harper’s sadistic abuses, her particular experience cannot cohere into a revolutionary movement among the prisoners. Just as they are a narrow group of marginalized persons, Stark’s marginalization is of a more extreme kind that fewer are subject to.

Caged still seems to leave open the possibility of some revolutionary potential for Allen even as she joins Powell’s crime ring. The film ends on a dour note, however, a revolution of a door rather than an overturning of society. When the warden, Benton, is asked what to do with Allen’s file upon release, she replies: “Keep it active. She’ll be back.” Her return will be precipitated by the impossibility of making legible the scope of her suffering. The status of anti-social woman is conferred only because there is undisrupted normal life that so many enjoy.

Weekly Reading List

“Creating a cinema that speaks to humanity,” an offhand comment by Charles Burnett in his Criterion Closet video, feels like the key to understanding his work. It is a little bit puzzling, I think, to make sense of Killer of Sheep (1978) and The Annihilation of Fish (1999) together. But thinking about them as speaking to humanity, maybe channeling that “compassionate gaze” I wrote about in May, helps bring them together.

There will never be a better Criterion Closet than this one.

Emmy promotional tours are in full swing. These roundtables are usually my favorite part.

The thumbnail of this video shows competitive fighting game player Justin Wong and all-star commentator James Chen in the commentary booth for Capcom vs. SNK 2 (2001). You would be forgiven, then, for being surprised by the fact that Justin Wong is playing in this top eight. How does he fulfill his commentary duties and finish out his tournament run? It’s absolute cinema.

Until next time.