Issue #389: Are Cops Too Smart for Detective Fiction to Flourish?

There is a future world where the Paradox Newsletter publishes a unified theory of detective/crime/mystery fiction. Putting everything involving PIs, solvable or unsolvable plot unknowns, and cops into its proper place and contextualized in relation to each other. It is a framework with seemingly limitless malleability that works in various aesthetic forms, artistic movements, cultures, and time periods. But, today, you will have to settle for the highly dis-unified commentary on some very different works within this exceedingly large umbrella.

Ballard and Bosch

“Neo-noir” comes up less often than you might think discussing Amazon Prime’s improbable hit Bosch (2014). The show ran for ten seasons (seven as Bosch, and three as Bosch: Legacy [2022]) with Titus Welliver in the titular role of ornery detective Harry Bosch. Bosch and its spinoff, Ballard (2025), are playgrounds where character actors get their due. Bosch transforms Welliver into a leading man and Ballard is the first series regular credit for the outstanding John Carroll Lynch.

Bosch didn’t grab me at first, though I’ve given it another chance. I’m enjoying the second season a lot more than the first. It leans more into the noir of it all, with lingering shots of Jeri Ryan’s silhouette framed in a window taking long drags of cigarette.

Ballard is another story. I was immediately hooked, and loving the first season so much inspired me to revisit Bosch. Maggie Q as Renée Ballard (not very creative with their naming conventions) works a cold case unit with volunteers, including one of her former partners, a true crime junkie reddit poster, and a private security CEO who works as an LAPD reserve. The plot moves like a freight train, setting up elaborate thematic and narrative connections among the many threads. There’s a very retro-feeling ‘feminist’ orientation that is not always subtle but does always feel like the right thing for the story. Ballard’s unenviable posting leading the under-funded unit comes as a result of her making a sexual assault allegation against another officer, one of the major narrative focuses of the season.

Every performer in the show fires on all cylinders, but Q and Lynch especially. I would never think to put the two of them in a show together, let alone as cops, but their chemistry is electric. Lynch is the master of subdued, mournful looks as he reflects upon his personal failures or delivers bad news to the team.

Despite the severe subject matter and the bleak circumstances that initiate the plot, Ballard is a very funny show. It is evocative of Veronica Mars (2004), not just because it involves a woman detective who is working to resolve the trauma of sexual assault, but because it presents extreme character archetypes to deliver humor in an otherwise very dark show. The primary comic relief comes from Ted Rawls (Michael Mosley), doing his best impression of Ed Helms’ Andy Bernard, and Colleen Hatteras (Rebecca Field), the aforementioned reddit denizen. As these things tend to go, both characters start out a little obnoxious but certainly grew on me. Ballard gives a lot of runway to its cast and the human drama never feels subordinate to the plot, but rather is a necessary complement.

Both Bosch and Ballard are procedurals, but I struggle to find substantial commonalities between them. Ballard is the one I prefer from my current sample size, but I am beginning to buy into the expansive, roving plots of Bosch as they evoke noir films and classics like Homicide: Life on the Street (1993). Luckily, Ballard is so good and self-contained it doesn’t require ten seasons of Bosch to make sense of it. For those who enjoy detective and police procedurals and aren’t offput by a little copaganda, Ballard is a must watch.

Gachiakuta and the Next Big Thing

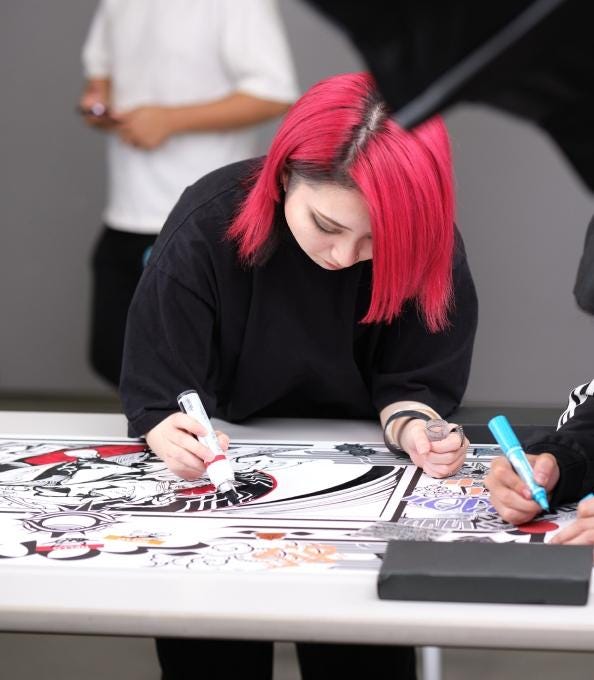

Lately, I have been pretty impressed by the anime and manga that studios and publishers decide to market heavily. The Kagurabachi (2023) manga is poised to be a pretty big anime hit. Dandadan (2024) has delivered as an anime adaptation. Though I haven’t watched the Wind Breaker (2024) anime much, the manga is really good. But today, there is a new anime with a major advertising push: Gachiakuta (2025). I’m hooked.

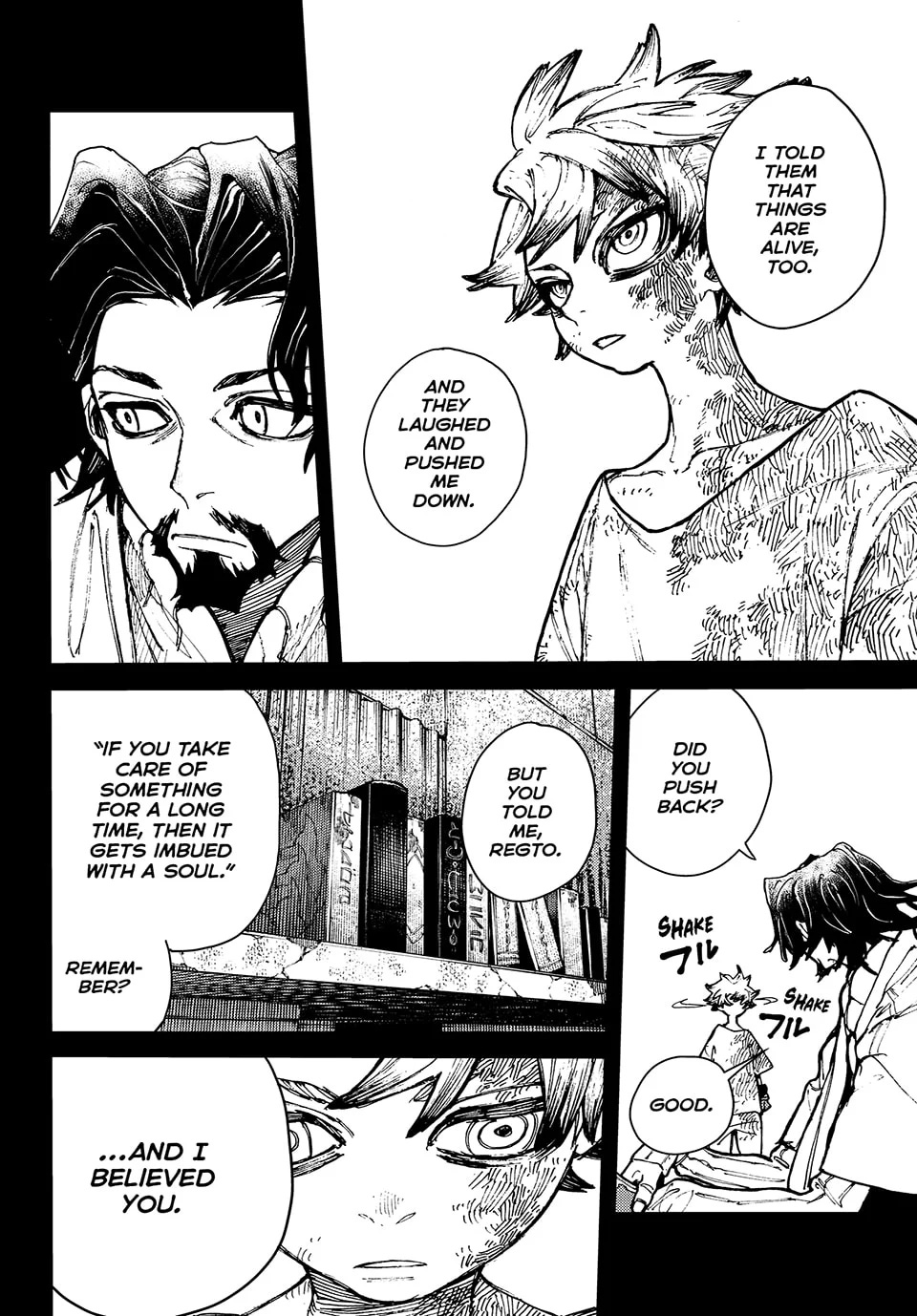

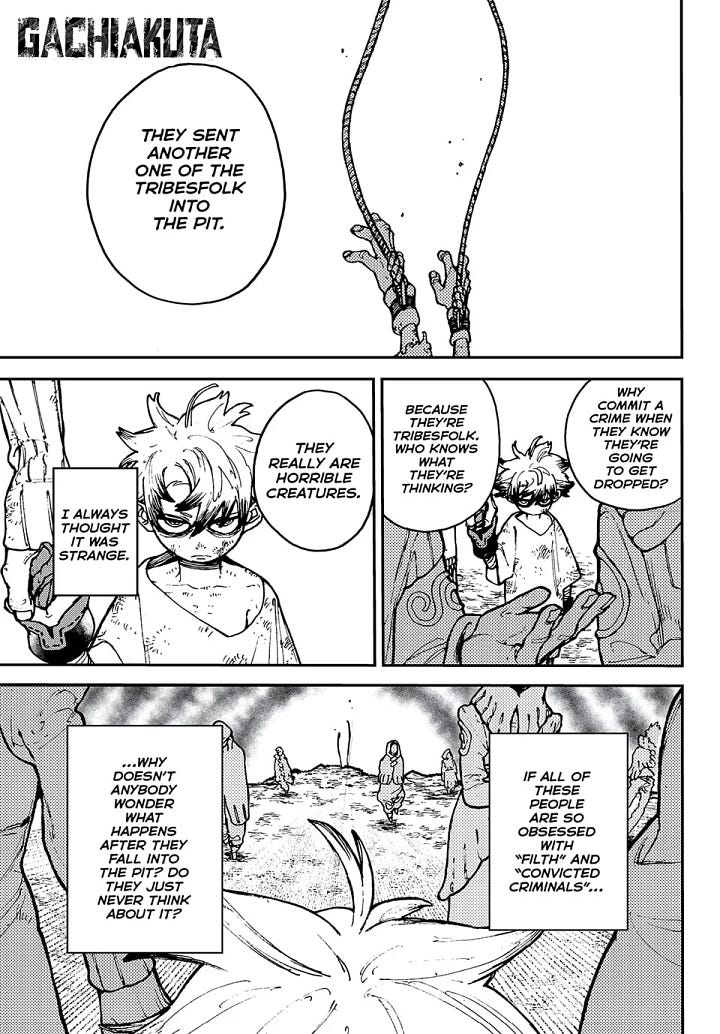

Adapted from Kei Urana’s 2022 manga, it follows Rudo Surebrec who is cast out from his dystopian, class stratified society and forced to live at the bottom of an enormous pit. Unknown to his former neighbors, this pit is not an immediate death sentence but houses an entire society. One of the manga’s big mysteries at the outset is what exactly explains the relationship between Rudo’s previous plane of existence, “the Sphere,” and where he now lives, “the Ground.”

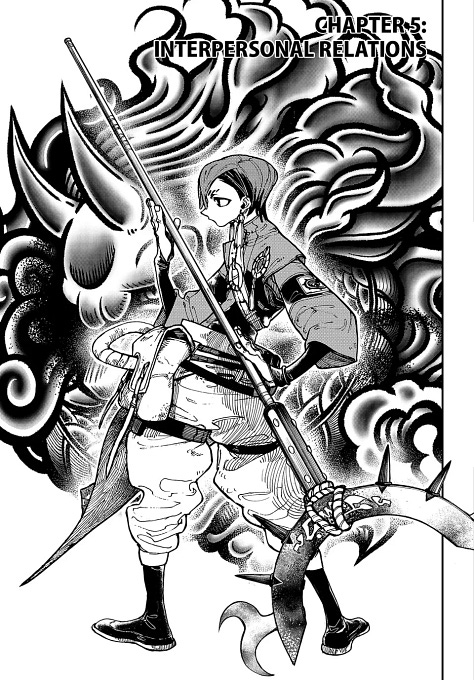

Urana’s work jumped off the page to me as similar to Soul Eater (2004). It’s no accident. She names Soul Eater as her favorite manga and worked with its author, Atsushi Ohkubo, as an assistant on his Fire Force (2015) manga.

There’s an obvious eco-critical bent to Gachiakuta — the title translates literally to “legit trash.” Rudo recovers and refurbishes discarded items that his wealthy counterparts throw away. His genuine belief in the value of inanimate objects is what gives him special powers in the logic of the plot.

Each superpowered “Giver” imbues some object important to them with energy that turns it into a weapon. This is an opportunity Urana uses to create some unconventional armaments.

It is not as if the tropes and ideas of Gachiakuta are particularly groundbreaking, but Urana focuses on social exclusion and prejudice in ways that lend themselves to a little bit more close reading.

I found echoes of the Alenka Zupančič piece I wrote about last week. In the world of Gachiakuta, the weak and impoverished are treated as a malignant contagion, threatening precisely because of their lack of social power. Zupančič writes in “Paranoiac Power” (2025):

Being weak (“emasculated”) is seen as contagious; it immediately corrupts the nature of the strong and powerful. This is why, for example, a simple mention in schools and kindergartens of the existence of gay and trans people is deemed capable of immediately corrupting the eternal and innate Nature of children, turning them all into gay or trans people—that is, into “emasculated people.” Similarly, immigrants are persecuted precisely when they are already most vulnerable, because of their precarious status, and not simply as representatives of some other, alternative potency.

To be sure—and similarly to the “deep state” reference—there is also the idea or fantasy of an alternative potency threatening to weaken and “replace us.” But again, most of the immediate fights and battles are fought against the weak, rather than against the strong.

The template here is quite simple—as well as nauseating: when someone is down and vulnerable, keep kicking them until they die or crawl away.

Urana, then, shows in Gachiakuta a strong understanding of this structure of power, paranoia, and disavowal.

Shounen manga doesn’t always deliver on its intellectual promise. But, one way or the other, I think Gachiakuta is worth reading.

Weekly Reading List

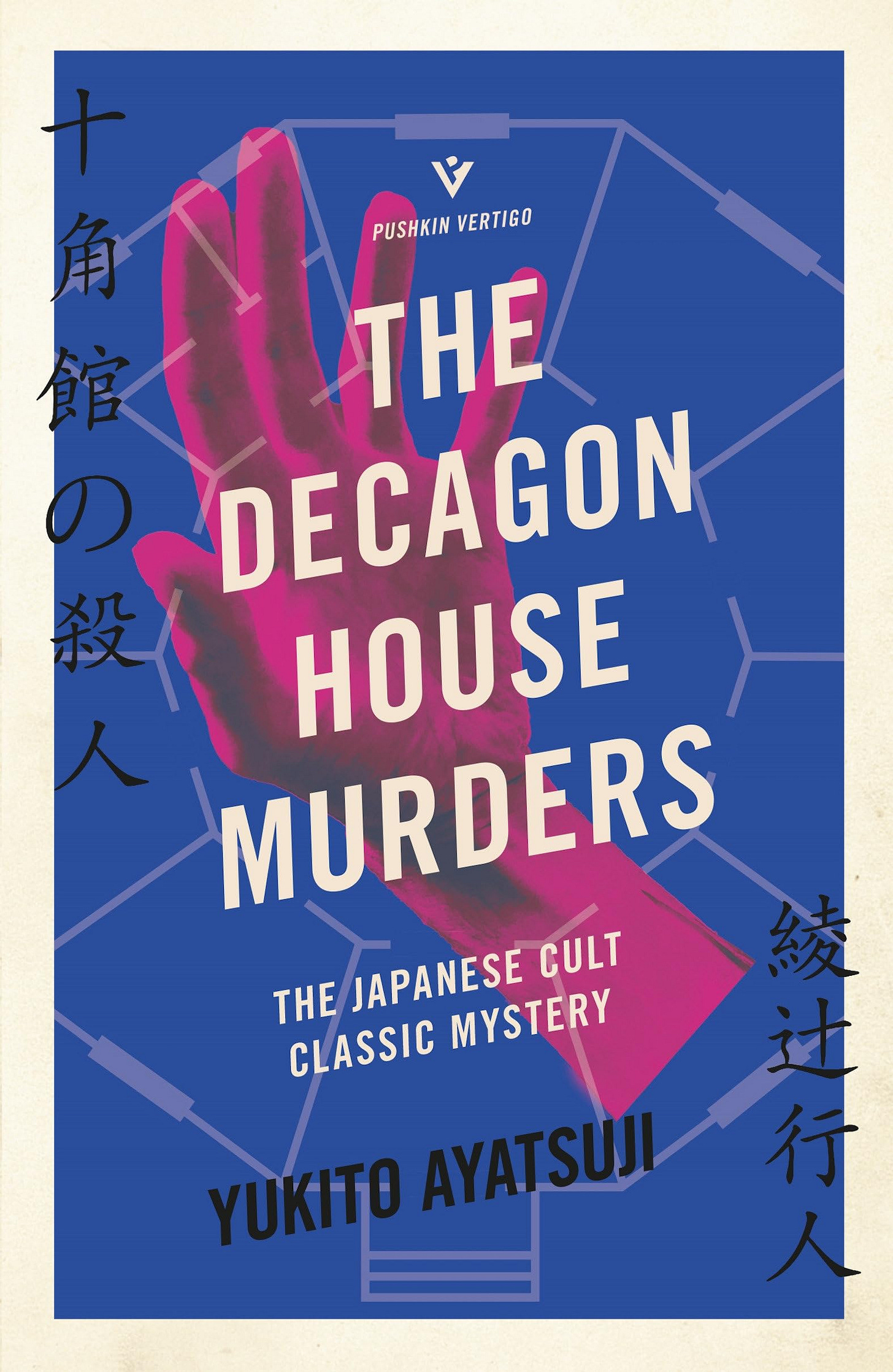

I read The Decagon House Murders (1987) front-to-back yesterday. It’s another example of the honkaku mysteries I wrote about a few weeks ago.

Ayatsuji’s version of the genre is by far the best I’ve read thus far. He sets up his characters to stage some of the critical disputes about what the mystery or detective genre should be:

“In my opinion, mystery fiction is, at its core, a kind of intellectual puzzle. An exciting game of reasoning in the form of a novel. A game between the reader and the great detective, or the reader and the author. Nothing more or less than that.

“So enough gritty social realism please. A female office worker is murdered in a one-bedroom apartment and, after wearing out the soles of his shoes through a painstaking investigation, the police detective finally arrests the victim’s boss, who turns out to be her illicit lover. No more of that! No more of the corruption and secret dealings of the political world, no more tragedies brought forth by the stress of modern society and suchlike. What mystery novels need are—some might call me old-fashioned—a great detective, a mansion, a shady cast of residents, bloody murders, impossible crimes and never-before-seen tricks played by the murderer. (15)

Ayatsuji also uses his characters as mouthpieces to wonder if police have become too competent as a result of modern technology and if there is room for the preternaturally skilled detective in modern crime fiction. He eschews that trope in this novel, at least. But there is plenty of mystery to go around.

Event Calendar: Kurosawa Restorations Come to Coolidge in August

Added listings for a bunch of the Kurosawa restorations I posted about a letter or two ago. Tap in.

Until next time.