Issue #392: Zach Cregger, Brilliance in Our Time

Alternative header image, anyone? There’s no way I could edit this one to make it any better.

The Super Robot Wars series serves an important cultural function. They remind players of underrated 1970s mecha series said players may or may not have seen. I decided, inspired by Super Robot Wars V (2017), to finally watch Zambot 3 (1977).

There’s not a lot of reasons for me to have not seen Zambot 3. It is written and directed by Yoshiyuki Tomino, two years before Mobile Suit Gundam. It is universally hailed as containing the elements that define Tomino as an auteur. And the music is incredible.

Takeo Watanabe composed the score for Zambot 3, who would re-team with Tomino for Daitarn 3 (1978) and, most notably, Mobile Suit Gundam.

Zambot 3 is available, for now, on Archive.org.

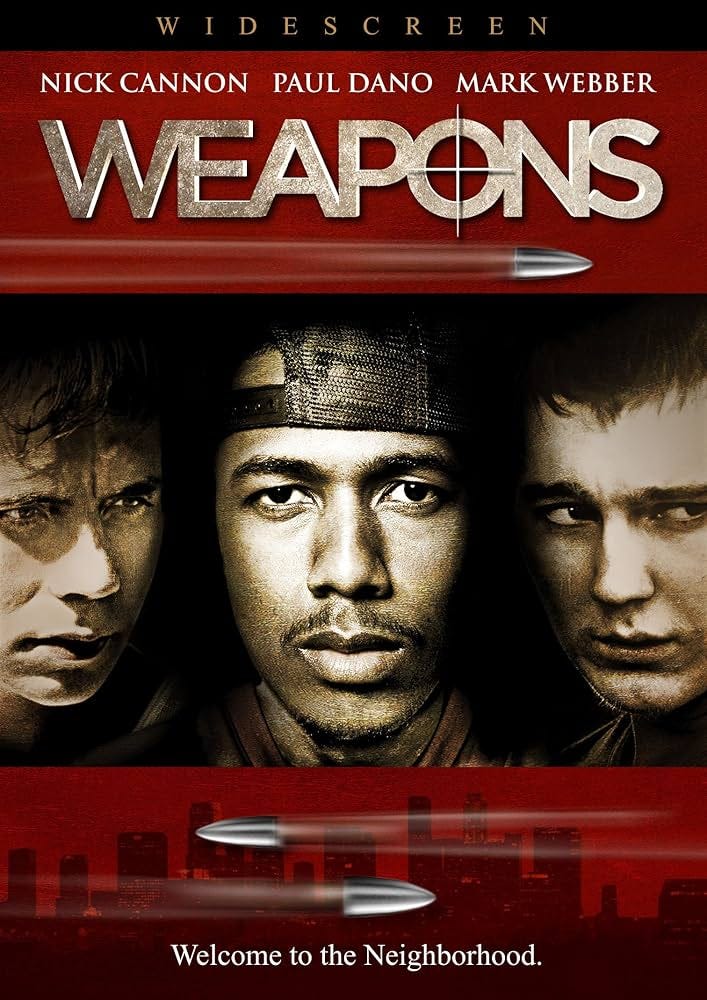

The Other’s Desire in Cure, Longlegs, and Weapons

I want to begin with two quotations that will orient my inquiry today. The first, from Lacan’s Écrits (1966), “it must be posited that, as a characteristic of an animal at the mercy of language, man’s desire is the Other’s desire” (Fink trans. 525). The second, from Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure (1997), “All the things that used to be inside me, now they’re all outside. So, I can see all of the things inside you, Doctor.” I read Cure, Longlegs (2024), and Zach Cregger’s Weapons (2025) as exemplary of the framework these two quotations avow. Across these films, the subject can only act under the auspices of the Other’s desire. Likewise, the determinative element of a subject exists outside, rather than within that subject.

“[W]ithout us thinking about it … it thinks”

My reading of these three films requires an elaboration of this quotation from Lacan. The latter part of the quotation, “man’s desire is the Other’s desire,” has been sublimated to the level of dictum. But what does this mean within Lacanian theory? There are a multitude of valences to what he claims here. Lacan’s “Other,” or “big other,” Autre written with a capital A in French, is a structural position that relates to the subject’s psyche in various ways depending on the period of Lacan’s thought. In Seminar III, in session from 1955 until 1956, Lacan begins to sketch the theoretical complexity of the Other elaborating Schreber’s view:

there is indeed an other for him, a singularly accentuated other, an absolute Other, an entirely radical Other, an Other who is neither a place nor a schema, an Other who says he is a living being in his own way … There is an Other, and this is decisive, structuring. (274)

Then, Lacan says, distinguishing himself from Schreber, “the Other must first of all be considered a locus, the locus in which speech is constituted” (274). In 1957-58, Lacan continues his engagement with Schreber and theorization of the Other in a written adaptation of Seminar III, “On a Question Prior to Any Possible Treatment of Psychosis” published in the fourth volume of La Psychanalyse and subsequently in Écrits, where it would be eventually translated into English.

Here, Lacan links but does not conflate the Other with the unconscious, “the unconscious is the Other’s discourse [discours de l’Autre]” (Fink trans. 459). Later he writes, “the Other is the locus of the kind of memory he discovered by the name ‘unconscious’” (Fink trans. 479). Evidently, then, Lacan means to make the relation between the unconscious which splits the subject and the Other which is a radical alterity relative to the subject1. This radical alterity, nonetheless, is something with which the subject will never be without:

It is rather striking that a dimension that is felt to be that of something-Other [Autre-chose] in so many of the experiences men have … has never been thought out to the point of being suitably stated by those whom the idea of thought assures that they are thinking. (Fink trans. 457)

The unconscious may have a grip on even the amorphous unit of existence that precedes the subject and can only be conceptualized from the symbolic vantage point of the subject, but the Other emerges in the injection of the something-to-subject into the symbolic order, a necessarily intersubjective process of identity constitution which extricates from the subject their jouissance. Lacan writes that the something-Other and Elsewhere, the agency and space which come together to form the structural position of the Other, are “permanent principles of collective organizations, without which it does not seem human life can maintain itself for long” (Fink trans. 458).

Lacan’s axiom, “man’s desire is the Other’s desire,” then, gets across a few meanings at once. The subject learns not just what to desire, but how to desire, by the figures that occupy the structural space of the Other. In Freudo-Lacanian logic, it is the subject’s mother figure. Beyond this didactic quality of the Other’s desire, though, is the essence of Freud’s Oedipus complex read by Lacan. The subject desires to be the object of the Other’s desire:

The whole problem of the perversions consist in conceiving how the child, in its relationship with its mother—a relationship that is constituted in analysis not by the child’s biological dependence, but by its dependence on her love, that is, by its desire for her desire—identifies with the imaginary object of her desire insofar as the mother herself symbolizes it in the phallus. (Fink trans. 463)

While the unconscious desire to be the unconscious object of the Other’s desire is a normal part of subjective development according to Lacan, perverse structure translates this unconscious desire to conscious demand and gives rise to a situation in which “the subject … makes himself the instrument of the Other's jouissance” (Fink trans. 697).

“So now we’re sure of one thing. That’s you.”

It is through this framework of the Lacanian Other that I want to elaborate the through line between Cure, Longlegs, and Weapons, beginning with Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara) and the line I quoted at the outset: “All the things that used to be inside me, now they’re all outside. So, I can see all of the things inside you, Doctor.” The Other makes sense of this exteriorizing of that which determines the subject. For Lacan, it is always exterior forces that define the subject as such. The mirror stage and the misrecognition of the self in the specular image marks the emergence of the subject into the Symbolic order and, necessarily, the constitution of the subject as such. Subjective existence requires the use of the Symbolic order’s tools, signifiers, “there is no need of a signifier to be a father, any more than there is to be dead, but without a signifier, no one will ever know anything about either of these states of being” (Fink trans. 464). But Mamiya misrecognizes himself not by taking an image as himself, but by being unable to identify the resemblance between the image and himself. In a frustrating exchange between Takabe (Koji Yakusho) and Mamiya, Mamiya can’t recognize himself in a photograph even after being told the photograph is him. After Takabe leaves the interrogation room, Mamiya stares into the one-way mirror seemingly confused by what appears in it.

If the mirror — Symbolic order — cannot render Mamiya’s subjectivity coherent or legible to himself, then one might turn to the radical alterity of the Other to understand him. The Other is the unknowable difference that makes intersubjectivity possible. Indeed, this is crucial for Mamiya, as he interacts with others without knowing who or what he is. Mamiya operates through the intersubjectivity the Other makes possible not to define himself, but to act in accordance with a seemingly pathological motivation to kill. The serial killings of Cure include the ritual and signature — an X cut into the body — characteristic of a specific killer. However, Mamiya does not kill anyone himself, instead utilizing the others he meets as tools to kill in this precise, peculiar fashion. Those who Mamiya seems to hypnotize become extensions of his subjectivity and his insatiable desire.

This encounter between Mamiya and those he influences is staged through the Other and establishes a kind of suture which makes the act of one subject a manifestation of another’s desire. The idea that one can act through another, making themselves the agent of the mechanism of another body, is the embrace of the Other which makes itself known in so many human functions. Mamiya recognizes the things outside himself that make him who he is, different from everyone else he encounters who appears to reject the notion of the Other and conceive of themselves as hermetically sealed individuated beings. Kurosawa, then, has created a cautionary tale in Cure. Rejecting the Other makes one particularly vulnerable to the form of influence that might be exercised through the channels the Other avails itself of.

The Stone Roller in the Crocodile’s Maw

Longlegs more or less follows the philosophical structure of Cure to, in my view, poor aesthetic results. Longlegs (Nicolas Cage) induces others to kill in a particular way. Longlegs is relevant in this reading of the Other for two reasons: simply as a reproduction of Mamiya’s logic where killing is not instrumental but desirous or pathological. Neither Longlegs nor Mamiya kill to enrich themselves, but to satisfy some kind of urge which in Longlegs gets sublimated to Satanic ritual. Longlegs as a film helps cohere a set of symbolic considerations that accompany this treatment of the Other as potentially threatening.

Longlegs also relates this kind of threat to femininity and excess. Lacan elaborates this angle in Seminar XVII (1991) when he describes the mother’s — in the position of the Other — desire and its relationship to the phallus:

The mother’s role is the mother’s desire. That’s fundamental. The mother’s desire is not something that is bearable just like that, that you are indifferent to. It will always wreak havoc. A huge crocodile in whose jaws you are—that’s the mother. On never knows what might suddenly come over her and make her shut her trap. That’s what the mother’s desire is. Thus, I have tried to explain that there was something that was reassuring. I am telling you simple things, I am improvising, I have to say. There is a roller, made out of stone of course, which is there, potentially, at the level of her trap, and it acts as a restraint, as a wedge. It’s what is called the phallus. It’s the roller that shelters you, if, all of a sudden, she closes it. (112)

Here, Lacan sketches out the imposition of the structural position of the Other that the mother might occupy and the attachment to the Other’s desire that the subject has — “man’s desire is the Other’s desire.” The phallus, this bulwark, redirects that threatening, consuming desire away from the subject, sometimes in the form of the Name-of-the-Father. Neither Mamiya nor Longlegs submit to this phallic authority, thus rendering their desire threatening. And Longlegs, particularly, embodies the feminine aspect of this threat analogous to the overbearing mother in the Other’s position. However, as Psycho (1960) illustrates, this overbearing mother is always an illusion the subject imposes on themselves. Even as Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) is, like one of Mamiya’s or Longlegs’ victims, the helpless instrument of an out-of-control desire, the desire that is unleashed in Psycho is Bates’ own, sublimated into the image of the overbearing mother he feared. Cure follows this logic more clearly than Longlegs, evidence of its superiority as a film. Ultimately Takabe takes up Mamiya’s role, showing the way in which Mamiya’s desire imposed on others is an obscene amalgamation of someone’s repressed desire with his insatiable desire. This is evident in the choice of each killers’ victim; they kill someone who has aggrieved them in some way or they may have some hostility toward.

“Leap to our doom”

Though Bates is quite different, he belongs in this continuum with Mamiya and Longlegs that also accommodates historical examples like Charles Manson, where another is instrumentalized through uncontrollable desire transmitted through the position of the Other. Other examples that can be read in this light to varying degrees include Johann Liebert from Naoki Urasawa’s Monster (1994), Tomie from Junji Ito’s Tomie (1997), and even Lorne Malvo (Billy Bob Thorton) from the first season of Fargo (2014).

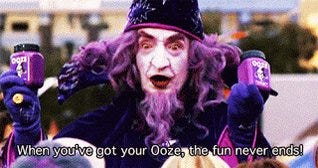

In my reading, this circuit of desire is even evident in the legend of the Pied Piper of Hamelin wherein the kidnapping of children through magical pipe demonstrates the repressed, or sometimes obvious, desire of children to escape a social order where they are accountable to parental oversight. Bryan Spicer’s 1995 Mighty Morphin Power Rangers: The Movie includes a related example: that of Ivan Ooze (Paul Freeman). Ooze is more Pied Piper than Longlegs or Mamiya, but he exemplifies the threatening kitsch of Longlegs and Gladys (Amy Madigan) that ties desire to femininity.

Ooze sells a product to children that, in turn, hypnotizes their parents. The parents first serve as manual laborers for Ooze, but ultimately Ooze directs them to kill themselves with the evocative, mono-tonally repeated phrase, “leap to our doom.”

Desire cuts across all angles of this scenario. Ooze imposes his desire upon these parents, and a certainly unintended reading of this Power Rangers film through the theoretical framework I am arguing for would suggest these parents have a repressed desire for suicide that is made manifest by Ooze’s will. Beyond the dynamic between Ooze and the parents he controls, the children first celebrate the absence of their parents, indulging in the childhood fun that parental oversight limits.

Though the children aren’t the ones controlled by Ooze, thinking of him in the mold of the Pied Piper suggests children might be particularly vulnerable to what is threatening about desire. Lacan’s account certainly corroborates this, as the mother-as-Other’s desire is particularly threatening to a child. “Normal” ascendency to adulthood, and the psychic changes it occasions, neutralize the threat to some degree.

“Just a touch of consumption”

All of this leads us to Weapons, Cregger’s newest film, where both children and adults are supernaturally motivated to kill through the rituals of a clownish witch, Gladys. Tracing the trajectory that includes Mamiya, Longlegs, and Gladys, it is important for my argument to distinguish, loosely, two kinds of murder. Up until this point (setting aside the minor examples of Perkins and Ooze) the examples I have examined are of serial killers. Mamiya and Longlegs induce others to kill in a particular, consistent way for their enjoyment. This kind of killing is not oriented toward a purpose. It is without traditional motive: the ingredient that, when subtracted from murder, requires the application of particular crime solving techniques innovated by the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit.

By contrast, Gladys is not a serial killer in the sense of Mamiya and Longlegs. Though ritual is involved in her killings, the killings themselves are not ritualistic. Gladys turns people into killers that might discover her ongoing imprisonment of Maybrook’s children. She then sends those killers after others who might expose her. Gladys kills with a traditional motive. Her murders are utilitarian or rationally motivated as opposed to Mamiya’s or Longlegs’ which are pathological or ritualistic.

What, then, ties Gladys to these other two? In Weapons, Other emerges not in the inducement of one to kill on another’s behalf. Instead, it is in Gladys’ subjugation of others to the end of syphoning their life force. Gladys uses Alex’s (Cary Christopher) parents and classmates as sustenance in the tradition of the child-eating witch in Hansel and Gretel. Gladys makes Mamiya’s existential peril, “[a]ll the things that used to be inside me, now they’re all outside,” literally. Her life is outside her, in the form of the children and family members she must extract it from. Cregger repeatedly analogizes her with a parasite, suggesting that the parasitic relation substantively locates one’s own life force in another. Gladys takes up the space of the Other to retrieve it.

“And they never came back”

The imperilment of children in particular is Weapons’ overriding anxiety. Justine’s (Julia Garner) attitude toward Alex is nearly as self-serving as Gladys’ disposition to his classmates. She stalks him, following him home with the mise-en-scène of Frank (Richard Brake) stalking his victim in Barbarian (2022). Her justification for wanting to speak to Alex is to make herself feel better, something Marcus (Benedict Wong), the school principal, immediately points out as a reason for why she should not speak to him. While it happens to be the case that Justine could uncover the mystery of the lost children and, indeed, Alex’s own confinement, her desire is only to sustain her affect through commiseration with Alex.

A more overt theme in Weapons, reflective of its title, is the analysis of gun violence in schools. The aftermath of the students’ disappearance is almost interchangeable with the aftermath of a school shooting. Alex, bullied as he is, is coded as a lone shooter. But Alex is the most sympathetic of the film’s characters. And he is our hero, ultimately turning Gladys into roadkill. The responsibility for gun violence in schools, and other wrongs a child might perpetrate, lies primarily with adults before children. This, too, is the threat of the Other whose overwhelming desire may subjugate a child to its whims. Though Lacan discusses the mother in this position more than the father, his analysis affirms only a structural position rather than the specific gender of a parent.

In a roundabout way, Alex transmits his trauma to his classmates through instrumentalizing them to kill Gladys. The missing children awakening to the eviscerated body is sure to be one of this year’s best moments in mainstream cinema.

“Not only can man’s being not be understood without madness, but it would not be man’s being if it did not bear madness within itself as the limit of his freedom”

What has returned the Other’s desire to the forefront of horror cinema in the form of Longlegs and Weapons? This question animates this entire essay, a taxonomy of the Other’s desire embodied by killers who don’t dirty their hands. Weapons provides the most salient answer, insofar as it suggests the limits imposed on children are transformed into the limits the superego imposes on adult subjects. Mamiya, Longlegs, and Gladys desire with no such limit, the grown versions of the dark alternative outcome in the Power Rangers film where the children let their parents leap to their doom to continue their endless revelry.

The formula for harm’s motive, where one person hurts another because they are upset with them, or for one’s own enrichment, seems quaint today. Across Cure, Longlegs, and Weapons, we see a world where the harm one might be subject to is inexplicable. If Cure is, in part, about the death of God as the guarantor of an ordered world, its themes are as relevant as ever in a world that is terminally disordered. As chaos stitches together bewildering rationalization for actions and beliefs, only coherent within the in-group from which they emerged, more complex intellectual work is required to explain these things from outside of those groups.

These films set out to demystify the actions that perplex us. What psychoanalysis reveals is these actions are sometimes motivated by an agency outside of us, and outside of everything.

Weekly Reading List: Eddie Palmieri All the Way Down

https://www.npr.org/2025/08/08/nx-s1-5495576/remembering-pianist-and-jazz-master-eddie-palmieri — Eddie Palmieri has been eulogized across the internet. I particularly liked NPR re-surfacing this 1994 interview of Palmieri by Gross. There’s a ton of insight into the innovations he brought to so-called “Latin jazz”:

PALMIERI: 1960 after I left Tito Rodriguez. It took about a year, and then by 1961, I started different forms of orchestra. But La Perfecta I started in late '61, which was the orchestra then that stood together for seven, eight years. And we had two trombones, flute, wooden flute, timbales, conga, bass, singer and I. It was a total of eight.

GROSS: Were trombones unusual for a Latin band?

PALMIERI: At that time, yes. They called us, like, the sound of the roaring elephants.

He also describes the repetition of montuno:

GROSS: In Latin music, there's a lot of repetition that the piano plays. Is that called montuno?

PALMIERI: That's exactly right. It's a montuno part, but it's called a guajira. You'll hear like, (vocalizing). That would be the guajira that I'm using there. And I'll use that, the guajiras behind the percussionist because the least amount of harmonic changes in Latin is where we get the highest degree of synchronization, which is what you're after. We simplify the chord changes. And there we get what we call masacote, which is the synchronization of the rhythm section and the piano and bass so that we're featuring that soloist that is showcasing himself or that I'm showcasing on the record, or in live, you know, live presentations to the public.

There’s also the quote from Robert Farris Thompson about Palmieri’s intro to “Adoracion,” the first song on side B of Sentido (1973), “Palmieri blends avant-garde rock, Debussy, John Cage and Chopin without overwhelming the basic Afro-Cuban flavor. A new world music, it might be said, is being born.”

Palmieri has no shortage of hits. “Adoracion” really does go crazy. And there’s “Vámonos Pa’l Monte” (1971) from the eponymous album, Superimposition (1970), El Sonido Nuevo (1966) with Cal Tjader. He even has a Tiny Desk.

But I have to say, without any concept of whether this is controversial or not, my favorite material of his is the La India record I wrote about back in July two years ago, Llegó La India Vía Eddie Palmieri (1992).

Supposedly, the genesis of La India’s collaboration with Palmieri happened by chance. And they would only work together sporadically afterward, never collaborating on a full album.

Beginning his career in the 1960s, his early output is a critical artifact of Puerto Rican culture in New York. His music predates the Nuyorican movement that emerges in the late 1960s, though his long career persisted through the movement’s most active periods. His activity as a burgeoning jazz musician occurs in the tale of anti-Puerto Rican sentiment, where various New York news outlets enumerated “The Puerto Rican Problem” describing “unwanted, unassimilable Puerto Ricans” in New York (A Puerto Rican in New York 9).

Palmieri and his contemporaries emerge precisely in response to this repression, but also benefit as it abates and the cultural attitudes toward Puerto Ricans shift in the 70s and 90s. His artistic innovation required this milieu of antagonism and synthesis.

This history will live on in his music, forever.

Event Calendar: Movies at Your Megaplex

Added some nationwide (USA) movie release dates to the calendar. Hopefully, you can see these at your local corporate theater on or around the dates listed. TBD if I’ll keep having stuff like this on the calendar.

Until next time.

It is worth noting that other Lacanian theorists have read Lacan’s account of the Other in “On a Question” differently. In Reading Lacan’s Écrits (2020), Stijn Vanheule writes, “Note that in this line of reasoning Lacan’s concept of the Other is not referring to the other qua interpersonal figure, or to language” (178). Vanheule goes on to explicitly make the Other here and the unconscious synonymous (179).

However, Vanheule does not square this with his own reading further on in his analysis of “On a Question.” He reads Lacan as saying, “the unconscious is made up of signifiers through which the dimension of Otherness is expressed” (179) and “[t]he question arising from the Other not only determines the subject, but also shapes his relationship with other people (a in the L-schema) and with the world” (180).

Finally, he seems to adopt the view of Other as structural position relative to the Name-of-the-Father when he describes the Name-of-the-Father as “the signifier of the law” that is “the context within which the subject and Other interact” (184).

Do these latter readings on Vanheule’s part make sense if one substitutes “Other” for “unconscious”? While Vanheule is right to distinguish Lacan’s use of Other here from the Symbolic order itself — something with which the Other is regularly conflated among other enumerators of Lacan — I dispute the idea that Lacan ever treats the Other as interchangeable with the unconscious.

Instead, what we see here is a preliminary sketching of the difference between the unconscious and Other, as I believe Vanheule’s own reading goes on to support to the extent that he claims the Other is determinative of the subject, opens intersubjective possibility, and is interacted with under the Symbolic Law of the Name-of-the-Father.

![Issue #286: Proof of [Insert Conspiracy Here] Inside](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!tEHH!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5eaab460-0e04-4a50-adb9-e9296977f7ab_960x540.jpeg)

The header image killed me.