Issue #396: Can We Get Much Higher? Spike Lee and Denzel Washington Say "Yes"

Last week, I presented the Paradox Newsletter Music League as if the entry is closed. I thought that was the case. This is the first time I’ve done one of these! But, as it turns out, you can still join. You’ll be a few rounds behind, but you’ll be in good company. Click here if you still want to get in on it.

This week’s playlist was “Shorties,” songs that are two minutes or less. I’ll link the ‘official’ version the app generated as well as copies of the playlist on Apple Music and Youtube Music, the latter two graciously made by league participants:

https://music.apple.com/us/playlist/music-league-short-songs/pl.u-NpXmoaGur6gxm

https://music.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL9gLI_LSfFbe4S3Tly-Ig-1W1MccaaYkZ

This week’s contest has people in a lather. There have been attempts at collusion, accusations of collusion (both by the same person…), people unable to submit their desired song because someone else got to it first. I have to imagine the duplicate song scenario is pretty uncommon. Because many people in the league are punk and hardcore oriented, there was a lot of debate regarding what genre is most appropriate to draw from for the short song prompt.

But people getting out of their comfort zone resulted in some variety. There were more acoustic and guitar-driven songs that I would have expected. Serge Gainsbourg and La Prendia were inspired choices.

Next week is “free parking,” meaning the prompt is to submit anything. Chaos will ensue.

Will be getting fanzine comps into the mail this week, but you can still order one here: https://paradoxnewsletter.bigcartel.com/product/shining-life-fanzine-compilation-volume-2

And you should.

Heavenest 2 Hellest

Adaptation and Inspiration

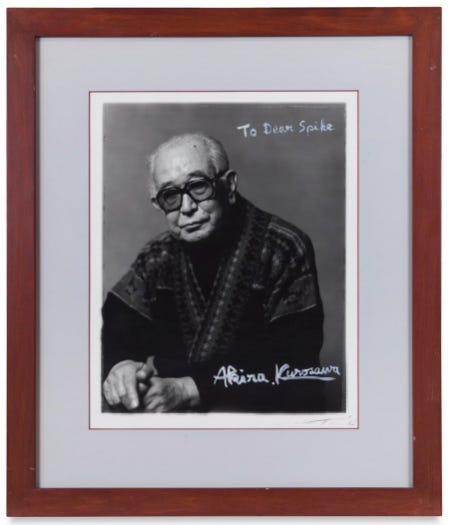

Doing press for Highest 2 Lowest (2025), Spike Lee is very clear: the movie is a reimagining of Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low1 (1963). This verbiage is so consistent and repeated, it might’ve come from A24’s marketing department. But I get the sense as I watch Lee’s various interviews, by how readily he corrects or reminds his interlocutors, that he really believes this line.

Why would Lee be so insistent about this? High and Low and Ed McBain’s King’s Ransom2 (1959) are credited as source material from which Highest 2 Lowest is adapted. Kurosawa Productions is among the production companies that made the film. Ko Kurosawa is an executive producer, part of the opening credits scroll along with a wide range of cast and crew. And Lee himself is a confessed Kurosawa obsessive.

Spike Lee’s relationship to adaptation might help make sense of Highest 2 Lowest as a reimagining. It sounds rather grandiose, doesn’t it? Spike Lee is the credited screenwriter on every feature film until 1996, where he would direct Suzan-Lori Parks’ screenplay for Girl 6 and Reggie Rock Bythewood’s screenplay for Get on the Bus. He is the sole screenwriter of She’s Gotta Have It3 (1986), School Daze (1988), Do the Right Thing (1989), Mo’ Better Blues (1990), Jungle Fever (1991), He Got Game (1998), and Bamboozled (2000), among this list essentially all of Lee’s most notable and beloved films. Though he is a credited screenwriter among two or more on Malcolm X (1992) (with Arnold Perl and uncredited contributions from James Baldwin), Crooklyn (1994) (with his siblings Joie and Cinqué), and Clockers (1995) (with Richard Price), Malcolm X and Clockers are book adaptations. Even when adapting something, Spike Lee has a heavy hand in every aspect of the creative process.

But Spike Lee is not a credited screenwriter for Highest 2 Lowest. The script, which came to Lee by way of the film’s star, Denzel Washington, is by first time screenwriter Alan Fox. This adds another vector of similarity to one of Lee’s most notorious failures, his 2013 remake of Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy. This Josh Brolin vehicle is unquestionably a remake, not a reimagining, obsequiously rigid in its re-staging of Park’s film. How Lee saw Oldboy in his oeuvre is hard to say. He was in no position to promote the movie as lavishly as the Highest 2 Lowest press tour, in the middle of a decade long creative slump including Miracle at St. Anna (2008), Red Hook Summer (2012), Da Sweet Blood of Jesus (2014), and Chi-Raq (2015). Oldboy also initiated a trilogy of questionable adaptations. Da Sweet Blood of Jesus remakes Bill Gunn’s Ganja and Hess (1973) and Chi-Raq adapted from Aristophanes’ Lysistrata (411).

Unafraid to stick his head into the maw of the dog that has bitten him so viciously, Lee returns to East Asian cinema with Highest 2 Lowest in a mode closer to that of Chi-Raq than Oldboy or Da Sweet Blood of Jesus. While Oldboy and Da Sweet Blood are fairly maligned, much of the criticism Highest 2 Lowest has sustained rings hollow, from the point of view of those who don’t know or like Lee’s work. If most people (Lee included, perhaps) agree Chi-Raq is better than the two films that preceded it, then the lesson of that film is that reimagining for Lee is far better than remaking. His heavy hand in the creative process is the hand of a master.

I love Highest 2 Lowest, and the reason I love it is because it is a film for film nerds. In every way that is important, Lee is rigid in his use of Kurosawa’s original plot. The details are the same in most ways one would expect. Just like Kingo Gondo (Toshiro Mifune), David King (Denzel Washington) over-leverages himself to buy his company to protect his life’s work. He is blackmailed by a foiled kidnapper who abducts his chauffeur’s child instead of his own. Causing the confusion, a green headband for Trey King (Aubrey Joseph) and Kyle Christopher (Elijah Wright) takes the place of a cowboy outfit for Jun Gondo (Toshio Egi) and Shinichi Aoki (Masahiko Shimizu). The exchange of money occurs on a train4, and the kidnapper is particular about the denomination of bills and geometry of that in which they will be encased. Like Gondo, King faces the ugly false choice5 presented by his scenario. The threat of King being divested of the possibility of recouping his investment because of public opinion rings truer than a boycott of National Shoes because Gondo refuses to pay Shinichi’s ransom.

A heavy hand is what separates a reimagining from a remake. And the way Lee transforms those distinctive elements of High and Low into a context that makes them feel more alive than ever shows just how great a filmmaker he is.

“You be out here shootin’, but you don’t miss no shots ever?”

David King is a record executive, not a shoemaker. His proficiency in cultural curation makes him a beloved public figure, unlike Gondo who is not widely recognized for his contributions to National Shoes. Lee needs to make a revision like this for the film to work. What is at stake for King is the preservation of culture, the critical transmission of Black music in context rather than divorced from it.

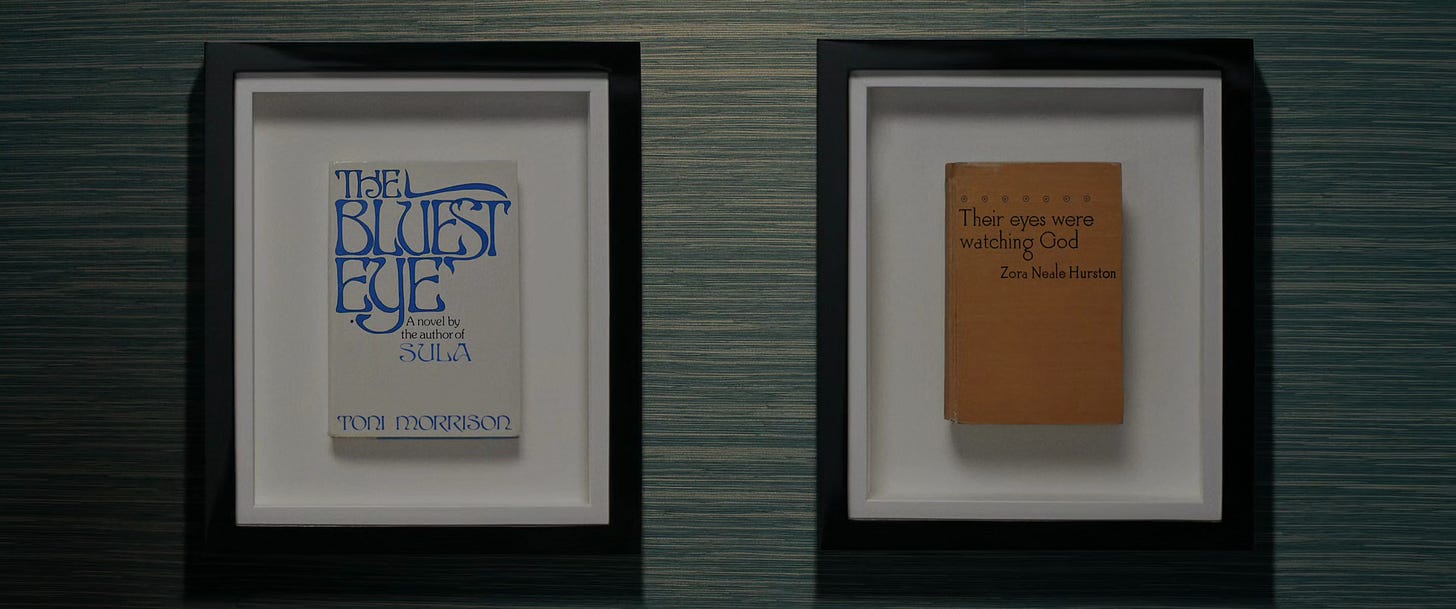

Lee lives up to this commitment he instills in his lead character. King’s house is full of Lee’s own paintings, Lee casts artists like ASAP Rocky, Ice Spice, and Princess Nokia in the film, there is even a close-up of Toni Morrison and Zora Neale Hurston novel covers toward the film’s conclusion.

The film’s greatest culturally connective tissue is not music, though, but sports. Across thirty-five years, Lee is still working over the themes of Mo’ Better Blues and, more importantly, He Got Game. King is a character from the mold of Denzel’s roles of Minifield “Bleek” Gilliam and Jake Shuttlesworth. Committed, obsessive, often at great personal cost. Todd McGowan writes about this character archetype in Spike Lee (2014):

After the depiction of Nola Darling, Lee depicts other forms of excessive enjoyment, including the attachment of Jesus Shuttlesworth (Ray Allen) to the game of basketball in He Got Game. As with Bleek and Nola, the excess troubles the character’s ability to interact with other characters at times damages the character’s self-interest. But Lee nonetheless shows that the excess defines the singularity of each character. Without excess, there would be no character at all. (36)

Although McGowan refers to Ray Allen’s Jesus in his account of He Got Game, the same applies to Jake:

The film makes it clear that Jesus’s singular basketball skill is the result of the excessive training to which Jake submits him as a young man. This excess begins even before he is born when Jake decides to name his son after Earl Monroe, a New York Knicks basketball player known as “Jesus” for his incredible skill. (37)

Jake reminds Jesus in a moment of conflict:

I pray you understand why I pushed you so hard! It was only to get you to that next level, son. I mean, you’s the first Shuttlesworth that’s ever gonna make it out of these projects, and I was the one who put the ball in your hand, son! I put the ball in your crib!

David King is a similarly exacting paternal authority to his son, Trey. Though the stakes are different, King aspires to have his son play for the New York Knicks. It is the ball, not the microphone, that King puts in Trey’s crib.

One might read into that decision all the phallic signification it entails, as King frequently reminds Trey of his childhood relative to King’s manhood.

This excessive investment in basketball cuts across Jake Shuttlesworth and David King and mediates their relation to their sons. King can’t help but see the Boston Celtics in the nondescript green headband his son wears.

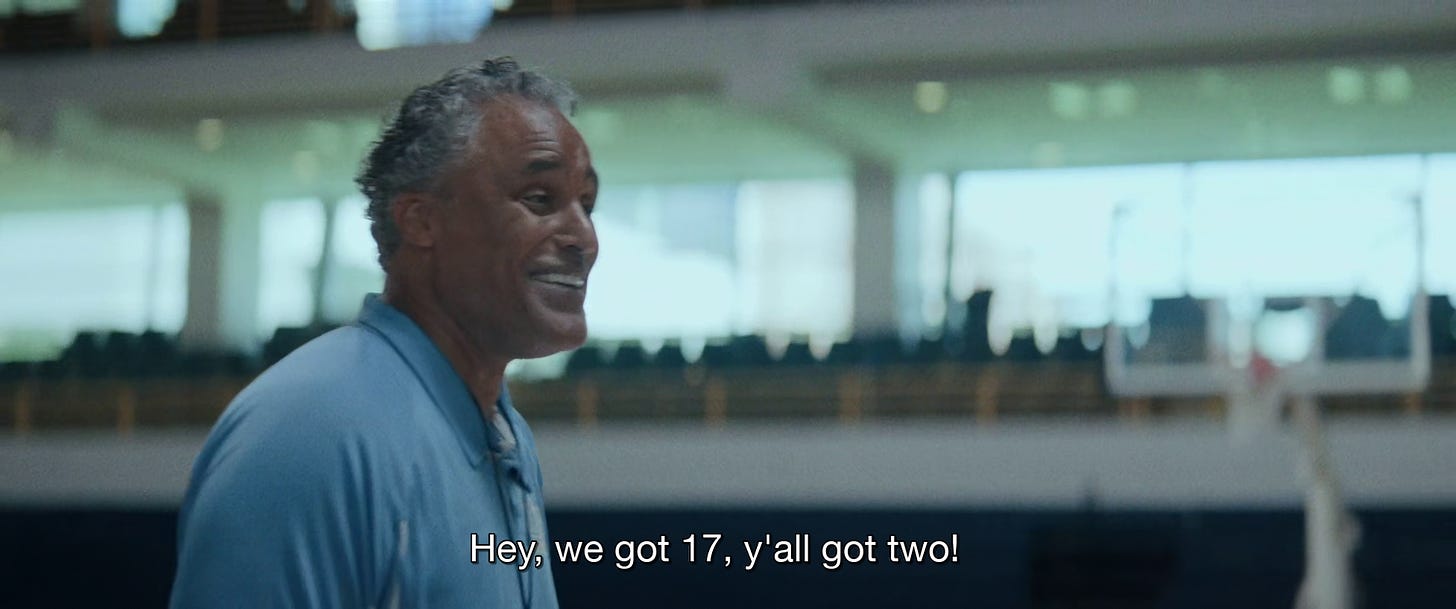

The excess of sports fandom even disrupts the film’s form, with direct address to the screen by an unnamed subway rider declaring, “Boston sucks!”

Sports becomes texture through which the characters in this film relate, beyond any other more restrictive identitarian lines. Even as Lee celebrates the specificities of Black and Puerto Rican culture, sports is the sublimated thing that defines New York as a multi-racial and multi-ethnic community. There is an allegorical dimension, too, of an ailing sports fanbase relative to one whose team is experiencing success.

Among the criticisms of the film that seem justified, there is a lack of stakes for King compared to Gondo. Even at the level of the film’s representation of space, the lowest low Highest 2 Lowest can show is so far above the gruesome filth of High and Low. King is never in danger and comes out clean. The drama and the tension is there, but the stakes are lowest. It’s as if the titles give the game away, one film trying and failing to anatomize the fall of a great man and the other focused on the juxtaposition of what it means to occupy different places separated by a great vertical distance.

Sports as an allegory, though, relieves some of this pressure from Highest 2 Lowest. Indeed, the stakes are not high when exploring this kind of resentment that ultimately has no impact on an individual’s life. Spike Lee’s material fortune has no relationship to the success of the New York Knicks. And the difference between a winning and losing team can change in an instant.

How many hours a day you on that?

Where the stakes of Highest 2 Lowest feel more significant than High and Low is in relation to the vicissitudes of public opinion. The great humiliation for Ginjirō Takeuchi (Tsutomu Yamazaki) is the way Gondo is embraced after paying Shinichi’s ransom. Takeuchi set out to turn Gondo into an embarrassment and disgrace, but he instead galvanizes the people and police force in service of regaining the ransom payment.

King is similarly beloved as a result of his paying Kyle’s ransom. But the idea that he might be “cancelled” looms large over his decision to pay.

With the opinions of the internet as the backdrop, Lee makes a broader critique of social media and “stan culture” through the parasocial relationship that drives Kyle’s kidnapping. While Takeuchi’s resentment of Gondo is driven by a combination of brute economic factors and psychological particularity, Yung Felon’s6 (ASAP Rocky) blackmail of King is the result of an unhealthy, protracted obsession.

The world in which Yung Felon inhabits is one of his own delusion. He worships King, his wife (Princess Nokia) reveals in the film’s final act.

Following from the song that originated the term, Felon even names his son after King7. This is a significant departure from High and Low. It makes the relationship between the blackmailer and the mastermind one of complex social figuration as opposed to relative randomness. Takeuchi and Felon both seem to have a pathological form of hatred, but Felon’s resentment is at least slightly more sympathetic as an aspiring artist who has been overlooked.

Highest 2 Lowest promotes a cultural embeddedness, through sports, literature, music, and cinema that is antithetical to the parasocial obsessiveness endemic to “stan culture.” One can and should appreciate art (and sports) without a fixation on the minute, personal details that are not readily available for public consumption.

This kind of investment is what the internet exacerbates, something Lee opposes to what he presents as authentic culture.

A Performance Fit for a King(o)

Aside from the film’s symbolic meaning, I was deeply moved by its performances. Denzel’s is dynamic and forceful. Since 2020, Washington has acted from the chest up. In The Equalizer 3 (2023) and Gladiator II (2024) it is particularly obvious that only his upper body is being filmed and a double is used for any scenes that involve a greater degree of movement. With some exceptions, that does not seem to be the case in Highest 2 Lowest. Although Washington claims to have never seen High and Low, he channels the intensity of Mifune’s Kingo, using the experience of having to act with his hands to get to a on-screen representation with the electricity and tension of Mifune’s furtive, unsettled movement in front of Kurosawa’s camera.

Though Highest 2 Lowest is not as meticulously blocked as High and Low.

Highest 2 Lowest is a movie clearly made by a fan. But it encapsulates and represents the different forms of cultural engagement and fandom and their consequences. Though they both may represent different forms of excess, Yung Felon seems to fit into Lacan’s neurotic structure. By his delusional beliefs about what an encounter with King might mean, Felon makes his own identity contingent on propagating his delusion. The reality can never live up to that which Felon imagines. And, indeed it does not, the scales falling from his eyes is such a psychically violent circumstance he begs King to kill him.

At the same time, this maintenance of this obsession is what drives Felon to torment King. Felon can’t let his fantasy of King go, whether he is the fantasmatic hero or villain of Felon’s narrative identity.

This is a great lesson for all filmmakers who seek to adapt other work. Lee departs deliberately from Kurosawa’s original to give his film an incisive edge cutting across a contemporary social issue. Above all, it is the film’s height.

Weekly Reading List

The first episode of Kamen Rider ZEZTZ (2025) is playing on repeat on youtube. Right now.

Hajime Iida debut record, Hajime, is out this week. I am intrigued by tofubeats, primarily an electronic music producer, becoming a popular featured artist as a singer. But he has a distinctive voice, showcased here.

Event Calendar: Kurosawa Never Ends

A 4K Kurosawa restoration is making its way to Somerville Theater after the run at Coolidge.

Until next time.

My title for this section comes from a joke Erin made based on the literal translation of Kurosawa’s original title, Tengoku to Jigoku.

According to Studio Binder, Kurosawa hated the novel from which he adapted his masterpiece.

Lee suggests She’s Gotta Have It is his first Kurosawa inspired film, taking cues from Rashomon (1950).

This scene in High and Low always reminded me of a lot of the action in Richard Fleischer’s The Narrow Margin (1952) or the train scene in Fritz Lang’s Human Desire (1954). Lee says in Highest 2 Lowest he’s paying homage to William Friedkin’s The French Connection (1971).

See Lacan’s elaboration of Kant in Seminar XI pg 212.

Spike Lee is gonna have me writing some variation of “Yung Felon” like twenty times because of his naming conventions. C’mon man.

Eminem raps from the perspective of Stan, “If I have a daughter, guess what I’m call her? I’ma name her Bonnie,” taking the name from an Eminem song about his own daughter. At the end of the song, Stan kills his pregnant girlfriend and himself because he doesn’t receive a response to his fan letters.