Issue #398: Theory With No Restraint & a Euzhan Palcy Movie

This week’s Music League theme was “Movie Soundtrack”

I really enjoyed this one. We’ve already voted, so I don’t need to worry about putting my hand on the scale too much. I submitted Art Blakey’s “Caravan.” Was that exact version of the song in the movie Whiplash (2014)? No. Is it one of the best songs ever recorded? Yes. I was considering submitting it for the “Free Parking” round, but I figured it was justifiable as an inclusion in the “Movie Soundtrack” category. The voters thought so too. I came in second this round, which surprised me.

The incredible submission of “BATTLE WITHOUT HONOR OR HUMANITY” took the weekly victory though. And it’s well deserved. I wrote in the League comments about how this song takes me right back to Kill Bill: Vol. 1 (2003) which is what I think a good inclusion on this playlist should do. Also I didn’t realize Hotei named this song after the Kinji Fukasaku movies, which just makes it more awesome.

“You Could Be Mine” from Terminator 2 (1991) didn’t do too well but I thought it was a good pick. I don’t think of myself as a guy who likes Guns N’ Roses, but this one might’ve softened my view. “Goodbye Horses” probably would have been what I picked to win the day, submitted by my friend Ernie. I got lucky. “Fight The Power” also made the list, I think the Platonic ideal of “Movie Soundtrack” songs.

The upcoming category is called “No, But Seriously” and people have to submit songs that “are often mocked but you insist are legimately [sic] good.” I could have changed the description, but I only now realize the typo intact there is from Music League itself. Get it together. There are a lot of ways to slice this one, but I think it comes down to being able to submit something that obviously has taken on some kind of ironic cultural quality but you can also make a case for why it’s a good song divorced from a context that diminishes it. It will be fun.

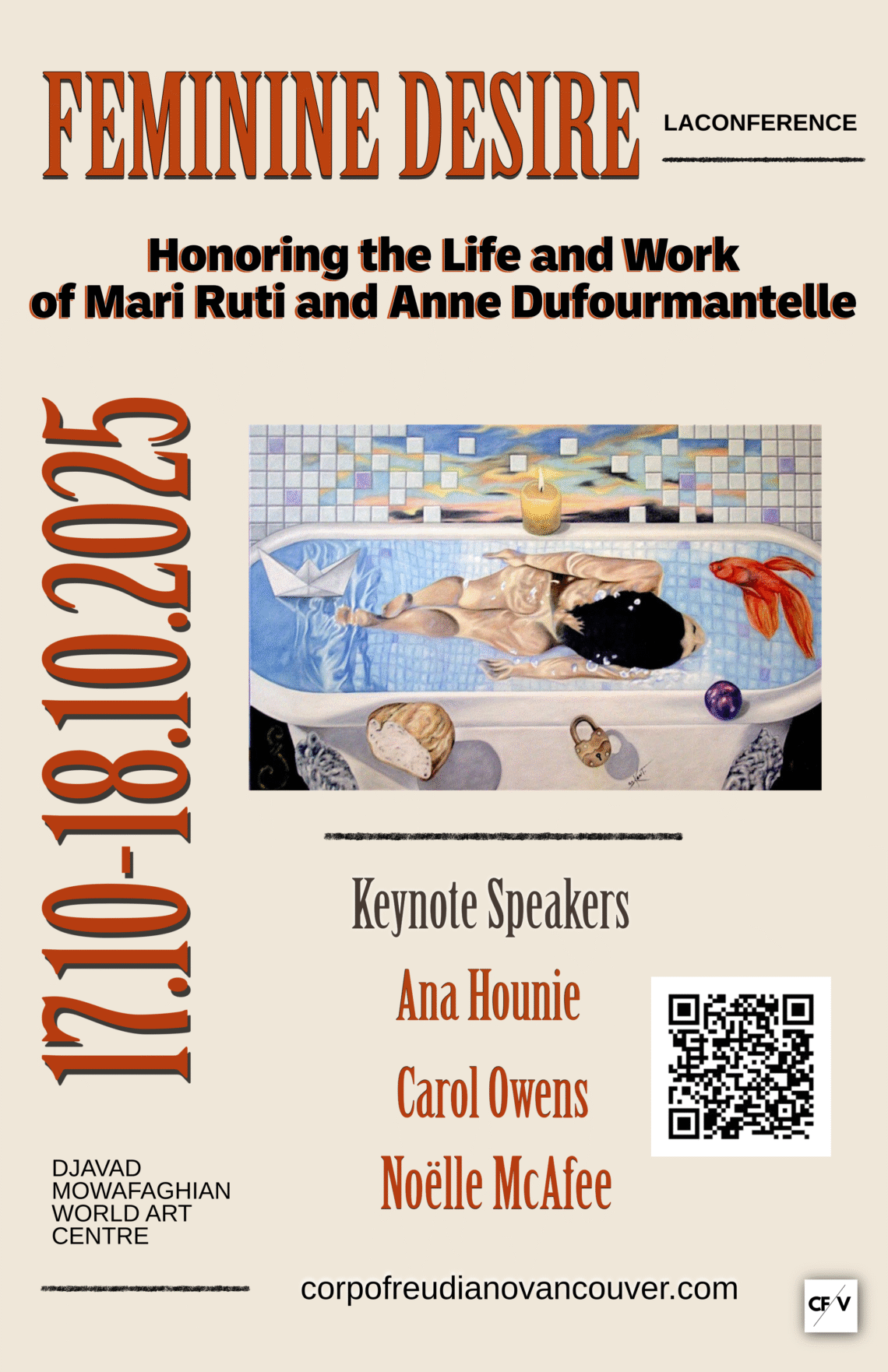

I also want to spotlight an upcoming conference organized by some friends of the letter.

https://corpofreudianovancouver.com/2025/08/25/la-conference-2025-registration/

The Corpo Freudiano Vancouver, fka Lacan Salon, will convene for their periodic LaConference in October of this year, on the 17th and 18th. One can attend both in-person at the Djavad Mowafaghian World Art Centre in Vancouver or online. They are a peerless group of scholars and I only wish I didn’t commit to presenting at so many conferences this year so I could’ve contributed to this one. I recommend, especially, the opening panels of each day where Alois Sieben and Clint Burnham will present. The conference has one, focused tract rather than a bunch of competing panels which I think is great. Attendees get the chance to have a really sustained discussion through the weekend.

Early bird registration prices end tomorrow, September 23rd, I think. Please give it a look.

Coming up this weekend, kind of an impromptu plan, we are watching Noroi (2005) in the Discord on Sunday at 7pm Eastern time. Discussion to follow.

If you would like to stream and discuss Noroi with us, please join our Discord server through a paid subscription to the newsletter.

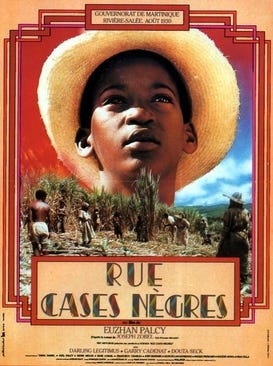

The conference I attended over the weekend is primarily what inspires this week’s writing. But the buried lede, a bit of commentary on Euzhan Palcy’s Sugar Cane Alley (1983), actually has its roots in teaching undergraduates. It might be shocking to some that I brought up Hortense Spillers in the course of my seminar discussion with undergraduates. But I did. The resonances with Palcy’s film are just too strong. The ideas there have really developed, as you’ll read here. Hopefully I’ll develop them further.

Redistributing Money, Justice, and Jouissance: Hortense Spillers, Jacques Lacan, and Sugar Cane Alley

Psychoanalytic transfers of paternal power are never peaceful. In most cases, “normal” cases, they involve the unrest of the unconscious. But in the allegories that define these scenarios for psychoanalysis, the transition involves explicit violence. Two myths characterize the Lacanian orientation to the paternal metaphor and where its power is concentrated: Oedipus Rex (429) and the story of the primal father in Freud’s Totem and Taboo (1913). Lacan comments on them both extensively in Seminar XVIII (2006):

It strikes me as impossible — and it is no accident that I run up against this word right from the outset — not to grasp the divide that separates the Oedipus myth from the myth of the father of the primal horde found in Totem and Taboo.

I will show my cards right away. The first myth is dictated to Freud by the hysteric’s lack of satisfaction, the second by his own impasses.

There is no trace in the second myth of what makes up the first myth: a little boy, his mother, and the tragedy involved in the passage from the father to the son — of what, if not the phallus?

In Totem and Taboo, the father enjoys, a term that is veiled in the first myth by power [or: potency, puissance]. The father enjoys all the women until his sons kill him, having made an agreement before doing so, after which none of them succeed him in his sexual gluttony. A term forces itself upon us owing to what happens by way of an aftershock: the sons devour him, each one necessarily receiving only one morsel, which thus turns it into a communion.

It is on this basis that the social contract comes into being: no one shall touch, not the mother — it is clearly indicated in Moses and Monotheism, which flowed from Freud’s own pen, that only the youngest sons are still allowed in the harem. It is the father’s wives who are targeted by the prohibition. …

Yet if this is, according to Freud … how the law originates, it does not originate from the so-called law against incest with the mother, which is, nevertheless, taken to be inaugural in psychoanalysis; for, in fact — aside from a certain law of Manu that punishes it with real castration …. — the law against maternal incest is, instead, elided everywhere. (138-139)

As is my tradition in quoting exceptionally long passages, I would like to elaborate with greater clarity the insights here. In short, a key difference between Oedipus and Totem and Taboo is the exacting nature of the incest prohibition. The mother as such, in fact, is barely featured in Freud’s account of paternal usurpation. Instead, this is a case where the sons seek to curtail their father’s enjoyment, and not to simply supplant his power and jouissance but to redistribute it. This idea of “redistribution” is crucial, as the counterweight to the notion of a concentrated paternal authority I mention at the outset.

Tracing these threads as they run through contemporary commentaries on the Oedipus complex that may or may not found the psychic life of the subject, Hortense Spillers’ “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe” (1987) is a vital and vitalizing intervention. Among her assertions and provocations within the text, Spillers shows how the structuring of the written1 genealogy of the enslaved person functions to subvert the incest prohibition. She posts a question about the governing matrilineal logic of U.S. chattel slavery, partus sequitur ventrem, “that which is brought forth follows the belly” or written in 1825 Louisiana’s civil code, “Children born of a mother then in a state of slavery, whether married or not, follow the condition of their mother.” Spillers writes:

But what is the “condition” of the mother? Is it the “condition” of enslavement the writer means, or does he mean the “mark” and the “knowledge” of the mother upon the child that here translates into the culturally forbidden and impure? In an elision of terms, “mother” and “enslavement” are indistinct categories of the illegitimate inasmuch as each of these synonymous elements defines, in effect, a cultural situation that is father-lacking. (79-80)

Spillers’ word choice here is anticipatory of the Lacanian view of lack. She is also responding here to the insidious and racist “Moynihan Report” (1965), Moynihan asserting that Black Americans suffer as a result of “a matriarchal structure which, because it is so far out of line with the rest of American society, seriously retards the progress of the group as a whole” (Moynihan 75, Spillers 65). Spillers goes on to point out in a parenthetical aside, “Moynihan’s fiction—and others like it—does not represent an adequate one and that there is, once we dis-cover him, a Father here” (67). Spillers continues:

Moynihan’s “Negro Family,” then, borrows its narrative energies from the grid of associations, from the semantic and iconic folds buried deep in the collective past, that come to surround and signify the captive person. Though there is no absolute point of chronological initiation, we might repeat certain familiar impression points that lend shape to the business of dehumanized naming. Expecting to find direct and amplified reference to African women during the opening years of the Trade, the observer is disappointed time and time again that this cultural subject is concealed beneath the mighty debris of itemized account, between the lines of the massive logs of commercial enterprise that overrun the sense of clarity we believed we had gained concerning this collective humiliation. (69)

Though the line of inquiry each thinker pursues is different, one can’t help but notice a homology between a moment in the thought of Spillers and Lacan. Spillers shows how the woman, specifically the “African woman,” is absented in the history of the Middle Passage, a concealment beneath these “mighty debris of itemized account.” Spillers begins an attempt at excavating this subject here that many thinkers pick up, including Saidiya Hartman in “Venus in Two Acts” (2008). For Lacan, there is also a missing woman in Totem and Taboo, particularly in his contrasting of the myth of the primal horde to Oedipus.

All of this brings me to the convening of the Psychology and the Other conference this past weekend and the keynote by Hortense Spillers, “Riding with Oedipus.” Just as Spillers responds to the sweeping claims of Moynihan in “Mama’s Baby,” “Riding with Oedipus” confronts another provocative claim by a much more sympathetic thinker, Frantz Fanon. In Black Skin, White Masks (1952), he writes, “it would be fairly easy for us to demonstrate that in the French Antilles ninety-seven percent of families are incapable of producing a single oedipal neurosis” (Philcox trans. 137). Spillers defines this oedipally immune subject as a “figure [who] takes his place alongside a repertoire of characters who inhabit our 20th … and 21st century imagination about the complicated personality who emerges on the other side of slavery and colonization.” In the brief survey of Spillers thought from 1987 to 2025, this much is clear: the subject of post-coloniality and post-enslavement is neither “father-lacking” (Mama’s Baby 80) nor in a state of exception that would cause such a subject to be immune from oedipal neurosis. To intervene in this question further, the best I can do is bring Lacan to bear.

For the scope of my off-the-cuff weekly newsletter, I cannot address the nuanced state of exception of U.S. chattel slavery with all the precision it requires. Suffice it to say, Spillers is a foundational cite for a necessary theoretical edifice considering the ontology of enslavement that includes Hartman, Fred Moten, Christina Sharpe, Frank B. Wilderson IIII, and many many others. However, I want to put to the test some Lacanian ideas that might bridge the gap between Spillers consideration of the father’s symbolic function in “Mama’s Baby” and “Riding With Oedipus.” For Lacan, the Name-of-the-Father, his account of exactly this symbolic function, does not presuppose an explicit genealogical link with a father or even a parent. Where Law exists, there is a paternal function. He writes in “On a Question Prior to Any Possible Treatment of Psychosis”:

the necessity of his [Freud’s] reflection led him to tie the appearance of the signifier of the Father as author of the Law, to death—indeed, to the killing of the Father—thus showing that, if this murder is the fertile moment of the debt by which the subject binds himself for life to the Law, the symbolic Father, insofar as he signifies this Law, is truly the dead Father. (Fink trans. 464)

And yet, without exception, this Law that is instituted cannot perpetuate itself precisely because of the illusory quality of phallic authority:

in this groping search for a paternal failing—the range of which is unsettling, including as it does the thundering father, the easy-going father, the all-powerful father, the humiliated father, the rigid father, the pathetic father, the stay-at-home father, the father on the loose … These are all ideas that provide him with all too many opportunities to seem to be at fault, to fall short, and even to be fraudulent—in short, to exclude the Name-of-the-Father from its position in the signifier. (Fink trans. 482-483)

It is the father’s word, then, that is called into question. This is the very word that would confer the authorized passing of a name, the actual surname, that is obscured in Spillers’ account in “Mama’s Baby.” Enjoyment is also at issue, as I write in my dissertation:

Freud exposes both the transmission of jouissance through identification and the cohesion of the siblings into a group in order to accomplish their goal. The two are part and parcel of one another. It is through the shared jouissance that the siblings, who identify with their father, are grouped together by their shared identification with an other. In the light of the idea of the “other jouissance,” what the brothers might come to find is that the enjoyment reserved for their father is not all it has been cracked up to be.

So, inevitably, or at least very often, the subject encounters the fraudulent nature of the paternal authority that is inscribed at the order of Law. This Law is full of holes, the foibles we might associate with any authority figure who does not deliver on what they promise. Finally, to relate this to Spillers and try to lengthen a thread, I must turn to Euzhan Palcy’s Sugar Cane Alley/La Rue Cases-Nègres (1983).

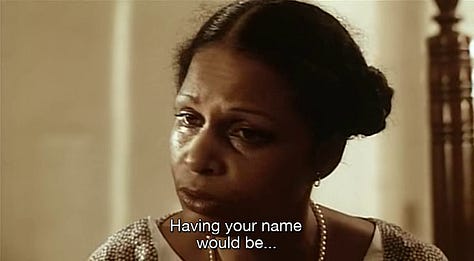

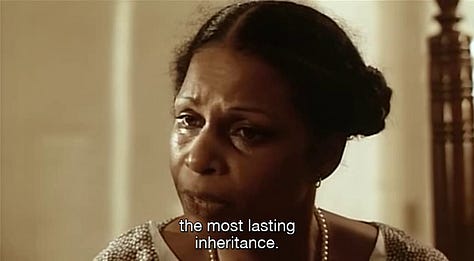

Palcy’s film is an adaptation of the semi-autobiographical novel by Joseph Zobel of the same name, translated a little differently in its English publication as Black Shack Alley (1950). In Palcy’s adaptation, the film follows José (Garry Cadenat), in the care of his grandmother Ma’Tine (Darling Légitimus), growing up on a sugarcane field. Though the workers, like Ma’Tine, are free, the film is critical of the wealth inequality and exploitation that has maintained the condition of enslavement despite ostensible freedom. Medouze (Douta Seck) reflects back on these changes to José, “The Master had become the Boss.”

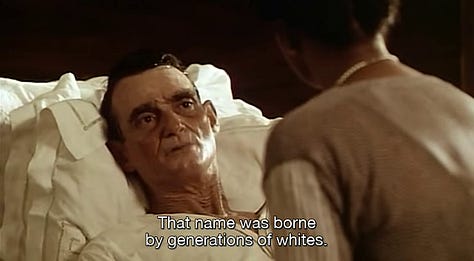

As José travels to attend school, he meets Léopold, the multiracial son of the owner of the cane fields and his Black mistress. Though Léopold’s parentage is not a secret, he is not formally or legally recognized as his father’s heir or son. Even on his deathbed, Léopold’s father refuses to acknowledge Léopold legally.

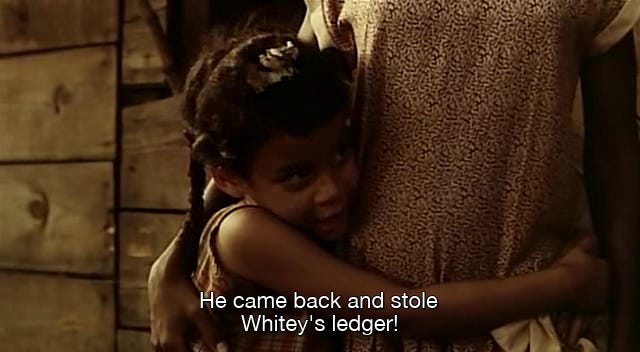

Léopold overhears this rejection, which begins a side plot critical to my consideration here. First, Léopold steals the financial ledger that proves the field workers are being underpaid.

He is arrested, but eventually goes on to instigate a strike that closes the film.

In Léopold’s usurpation of paternal authority, the transformation he undergoes is more radical than the sons consuming the body of their father to partake of his power and jouissance. The consequence of the failure of the paternal function expands beyond the confines of the anointed siblings. Because Léopold exposes his father’s wrongdoing and generates the political will to strike, he opens up the possibility of something being redistributed that is different from jouissance. In the words of the striking cane field workers, “money and justice.”

If the paternal function does not cohere around a particular subject, a father who passes their name to their child, perhaps the effects of its overturning are also diffuse. This is the model of paternal authority that Sugar Cane Alley explores.

Weekly Reading List

Prestige TV is not dead.

Event Calendar: Columbia Rarities at HFA

A lot of films start running this time of year in Boston, especially at Harvard Film Archive. Coincident with the school year. I can’t keep up with everything, but this week I added some of the most interesting rarities from their upcoming run of Columbia films. I’m especially excited for Mysterious Intruder (1946) and The Killer That Stalked New York (1950).

David Kornfeld, the head projectionist at Somerville Theater, once told a story before the run of a large format picture that there’s a film club in some middle American town that watches all of Somerville’s programming. Even if you don’t live in the region, I encourage you to check out some of these movies in whatever way you can manage. And tell me all about it.

Until next time.

This writing, the “official” documentation, which obscures paternity, also upholds one fantasmatic element of the racial imaginary. Namely, the fantasy that substitutes the contemporary nomenclature of “enslaved person” with “slave,” that presents a person (my terminology here needs a footnote within a footnote) extricated from a genealogical connection, eliding the fact of who birthed who, instead presenting the so-called “slave” as fungible and available for use as a commodity and tool or function.