Issue #399: Tatsuki Fujimoto's Nihilism in Chainsaw Man and Fire Punch

The “No, But Seriously” category revealed a lot about the group playing Music League. In a sense, it reveals an individual self-consciousness about one’s own music taste.

People disputed what qualifies. Is it enough for a song to be widely disliked among your peers and friend group? Someone decried the inclusion of pop hits, when from my perspective that is a body of work that is subject to frequent mockery among aesthetes like us. Since voting is all done now, I can share what I submitted:

My logic was pretty simple. This song has circulated as a joke or meme when I think it’s a great song. I listen to it all the time. Anything we want to wrest from that irony-tinged social circulation seemed like fair game to me.

Song for song, I may have actually enjoyed this playlist most of all. Erin submitted a Kesha song, bait for me to vote for. I appreciated “Jerry Was A Race Car Driver” for the first time. Erik wrote an essay about “Baby’s Got Her Blue Jeans On” which was pretty good. There are also songs on the playlist I just like and didn’t realize were hated, but the comments were convincing enough to explain cultural context I had missed.

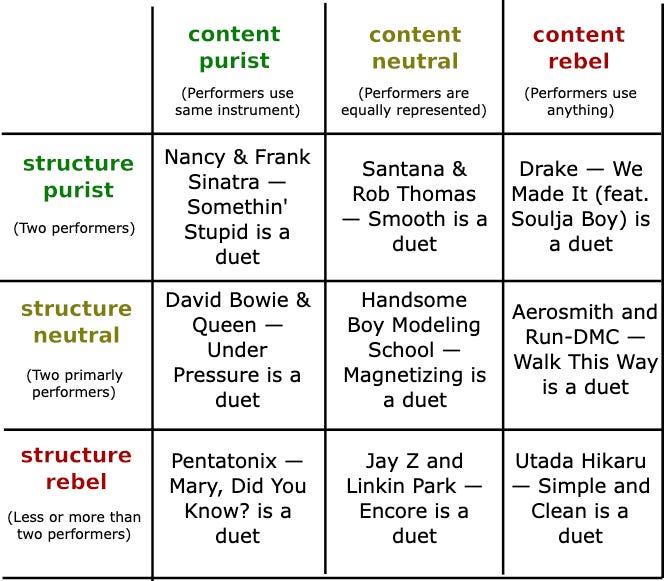

This week is simple: “Duets.” But what constitutes a duet? Does “Smooth” by Santana and Rob Thomas qualify? What about Kanye West and Rhymefest?

Someone could probably make a duet alignment chart. Actually I just made one in the last ten minutes or so after writing that previous sentence. Sound off in the comments or in the Discord if you agree.

I can count on my Music League members for some continued lively debate on this topic.

Tatsuki Fujimoto Unleashed

Ryan Colt Levy, Denji’s English voice actor, has a great line delivery in the Chainsaw Man - The Movie: Reze Arc (2025) trailer.

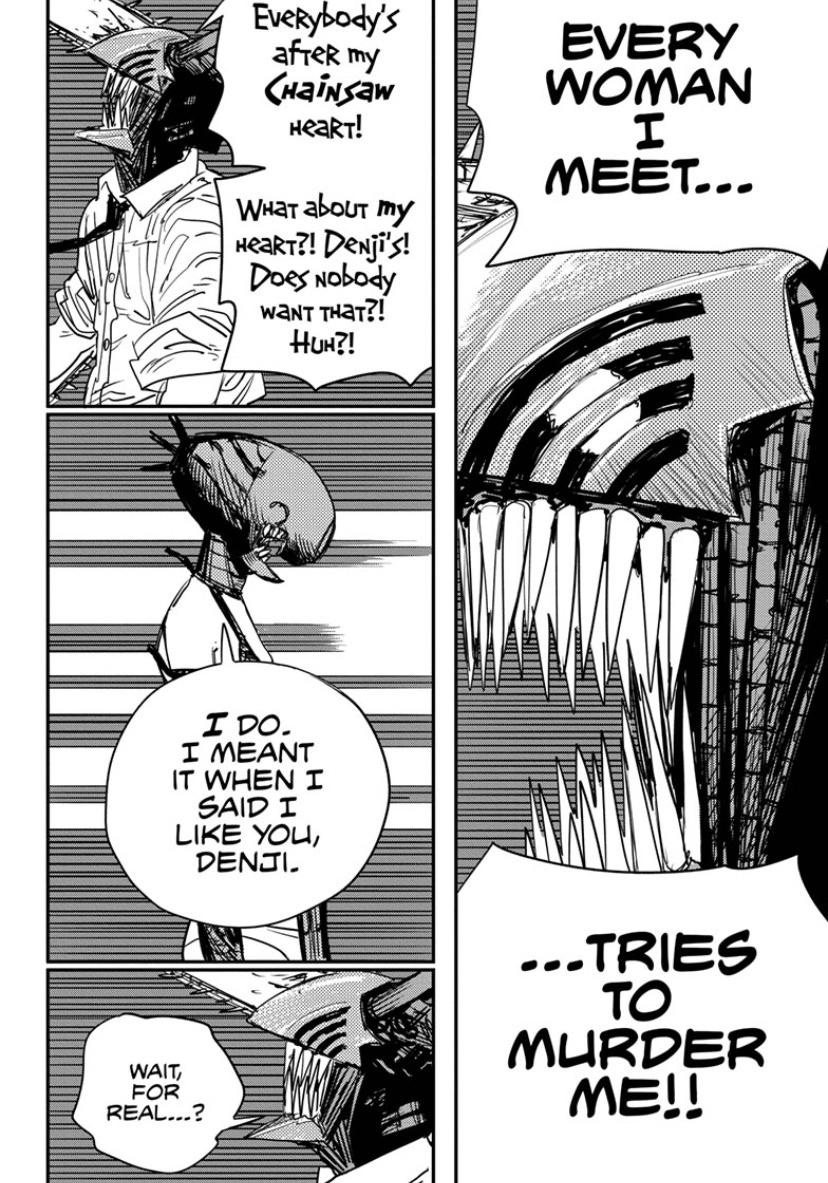

If you’re not as sympathetic to dubs as me, I was impressed by what he gets across in this line: “Everybody’s after my chainsaw heart. What about my heart? Denji’s heart? Does nobody want that?” As a voice actor, Levy has very few significant roles to speak of. Denji is a breakout part for him. He also does a good job at what is inherent to the work of Tatsuki Fujimoto, the original author of Chainsaw Man (2018) — conveying serious emotional weight within a ridiculous premise and absurd dialogue.

The trailer for the Reze Arc movie looks great, but it’s this line and Levy’s delivery that fuel my anticipation above all else. And it has reinvigorated my interest in close reading Fujimoto’s work more rigorously. I read the first 97 chapters of Chainsaw Man during its original run, and read this current “School Arc” through about 170 chapters before setting it aside. The manga has gotten increasingly surreal and impressionistic. The plot has never really been too important, but the “School Arc” spends a bit too long developing complex relationships between different organizations operating in the backdrop of the narrative.

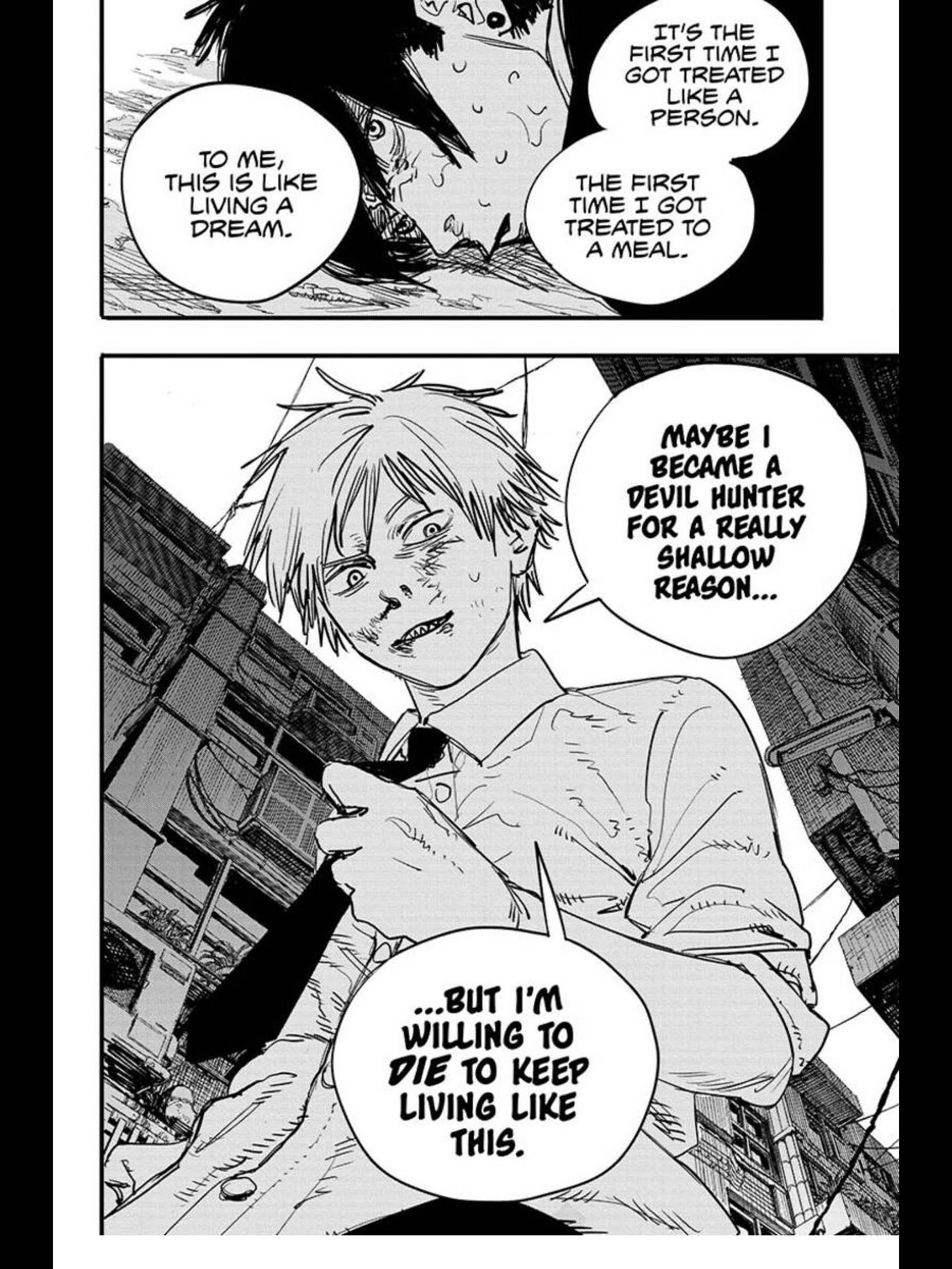

My complaints about the current Chainsaw Man arc aside1, there are some veins of thought related to the manga I haven’t mined yet. Among shounen manga, Denji is a unique protagonist. High-minded goals do not motivate him. He is not trying to be the best at something or find a lost parent or overturn a profound injustice.

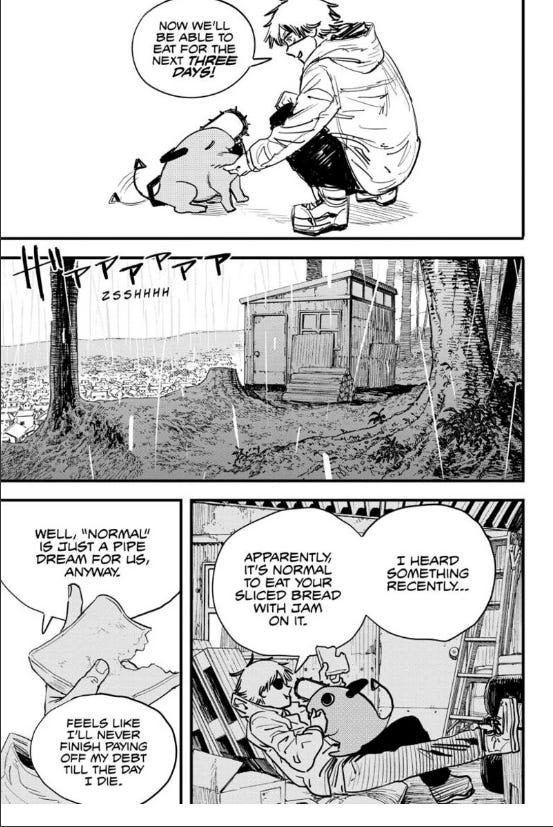

Instead, he seeks sense pleasures. Fujimoto sublimates Denji’s libidinal demands, having Denji share these goals where a more generically appropriate motive would appear in other shounen manga. Aside from being motivated by sex or praise, he also confronts the exigencies of human existence and works for shelter and minimal nourishment.

Denji’s underlying motivation, novel as it is, is enough to sustain a shounen manga that stands out among its peers. Even if you make the argument that Goku, for example, fights against extraterrestrial threats in Dragon Ball Z (1989) for his own satisfaction, Toriyama, Nishio, and Yamauchi never relate that satisfaction to the peril of poverty. Denji lives on the brink. On the one hand, he’s maladjusted because of his lengthy tenure as an indentured servant to the yakuza living in destitution.

On the other hand, he is a protagonist of the people unlike any other. His demands and unfiltered thoughts are distorted, perhaps exaggerated, thoughts of the audience that read the manga.

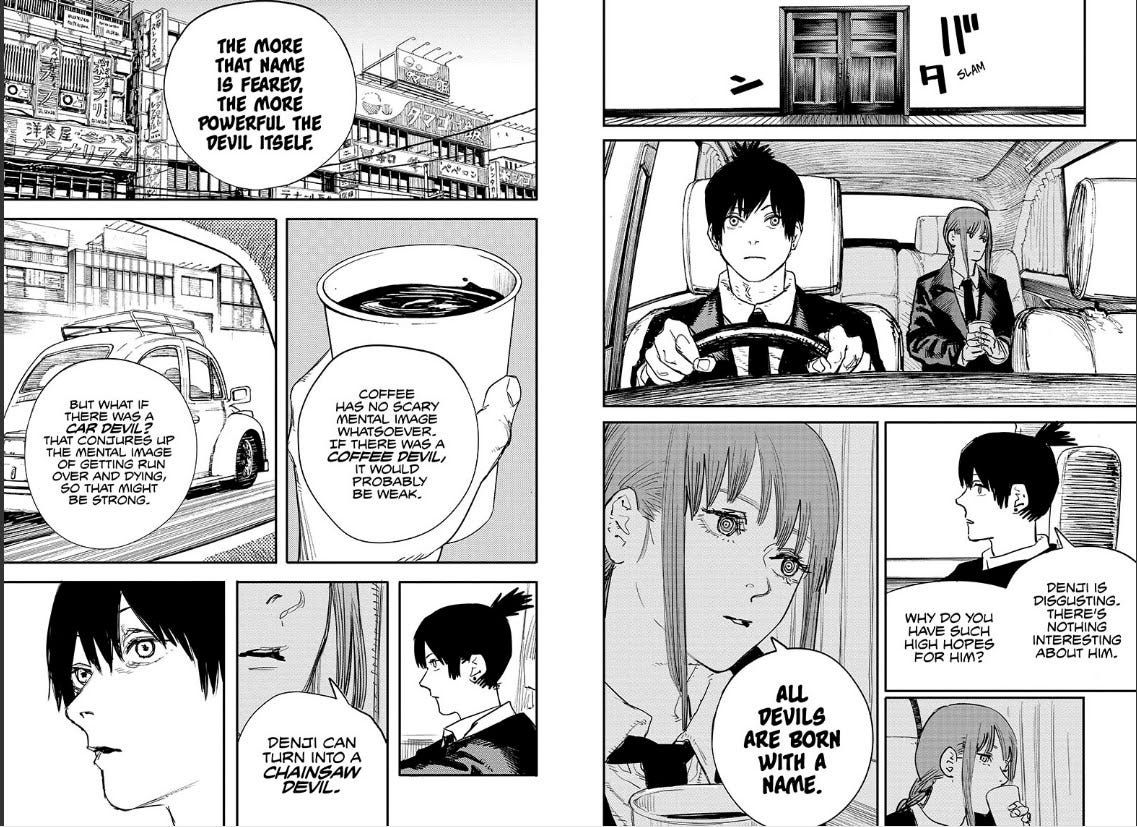

One of the major themes that emerges is that of reputation. Denji is motivated both by his self-focused sensuousness and the praise he receives from others. Devils, the class of monster that Denji both is and fights against, gain their power from their place in a societal imagination.

In episode three of the Chainsaw Man (2022) anime, “Meowy’s Whereabouts,” Makima (Suzie Yeung) says:

There isn’t a devil in existence that was born nameless, and the more a devil’s name is feared by the world, the more powerful it becomes. Take coffee, for instance. It might scald you, but it isn’t very intimidating, so a coffee devil would probably be weak. Cars paint a much scarier image, since plenty of people dread crashes or getting run over, which would make a car devil strong. What’s interesting is how Denji’s part devil. The chainsaw devil at that.

This is early warning of what becomes so critical to Chainsaw Man’s narrative, as Denji’s life and even his supernatural abilities transform based on people’s attitudes toward him. There’s also a gap, though, between the perception that gives Denji’s chainsaw devil its power and his base motivations, like the Lacanian signifier, “[t]hat is why he finds himself divided in this way, being represented all the same” (Seminar XVIII 2).

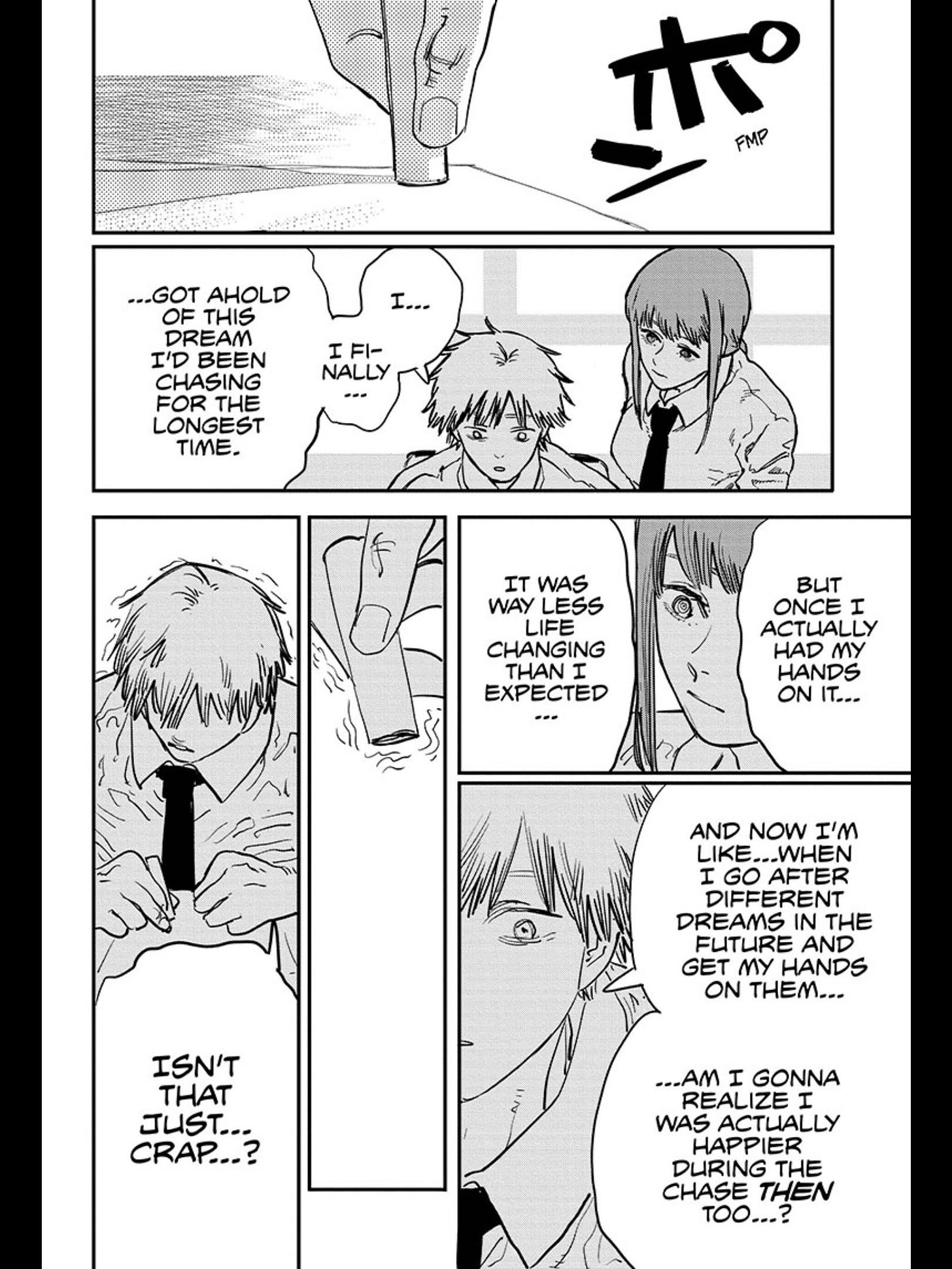

The power of the proper name, and the dignity it imposes on the otherwise fungible signifier, is just one of the Lacanian themes one might draw out of Fujimoto’s most popular manga. Denji also experiences the brute reality of desire’s metonymy.

There is rarely a question in shounen manga that the next triumph for the protagonist is meaningful. The next summit they scale is proportionately better than the previous one. Chainsaw Man, instead, opens up the possibility for calling this entire structure into question. Denji is always positioned between a form of relieve resulting from the satisfaction of his basic human needs and his impulse to seek something in the same way his colleagues (and generic counterparts) do. Ultimately, Denji is never oriented toward goals that facilitate social cohesion. Even his ascendency to the status of icon, as the manga progresses, is destructive. The public version of Chainsaw Man society embraces is a distorted semblance of Denji himself, the signifying substitution for its referent. This is the painful reality of the world that Fujimoto explores, where satisfying one’s desires rarely makes the world a better place. It often makes it much, much worse.

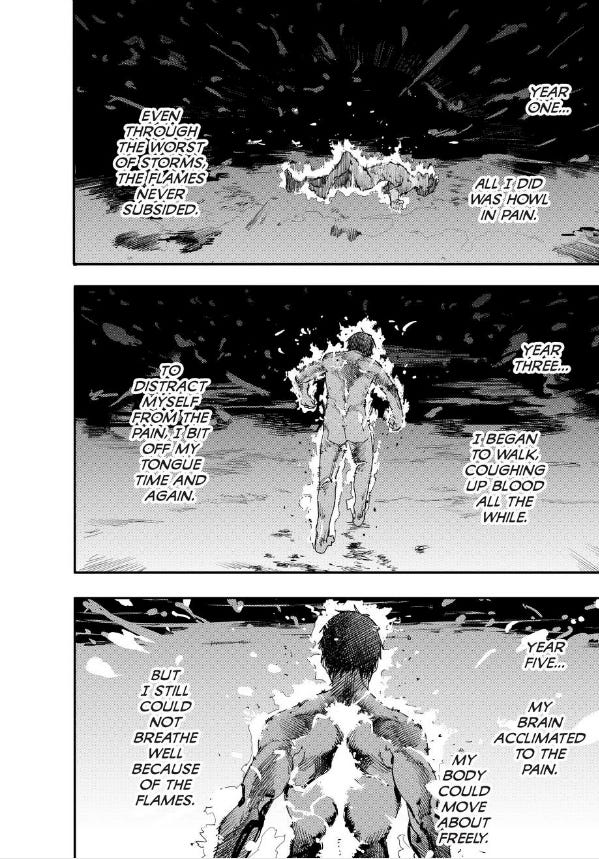

But there is no world that is worse than that of Fujimoto’s serialization before Chainsaw Man, Fire Punch (2016). Fire Punch has not been adopted into an anime. I’m not sure how it could. It includes some of the most obscene material I have ever seen in a shounen manga. And, yes, this is a shounen manga: it was serialized in the online Shōnen Jump+. The manga is a post-apocalyptic story following a young man, Agni, with regeneration powers who is lit on fire by a soldier of the last remaining city, Behemdorg. Agni’s powers are such that his body is constantly regenerated as it is burned. The fire, like just about everything else, can’t kill him.

Agni is a very different protagonist compared to Denji. They are both suffering, imperiled, proletariat figures. But Agni’s capacity for normal behavior and brain function is nonexistent as he constantly suffers mind-searing burns.

Agni’s state of being is fitting for the setting. The gruesome violence I alluded to, which includes some very bizarre examples of sexual violence and other sorts of unusual, salacious horrors, divorces the setting from modern context and sensibilities. What shocks the readers barely registers as unusual for the characters. It’s a world of “snow, starvation, and madness.”

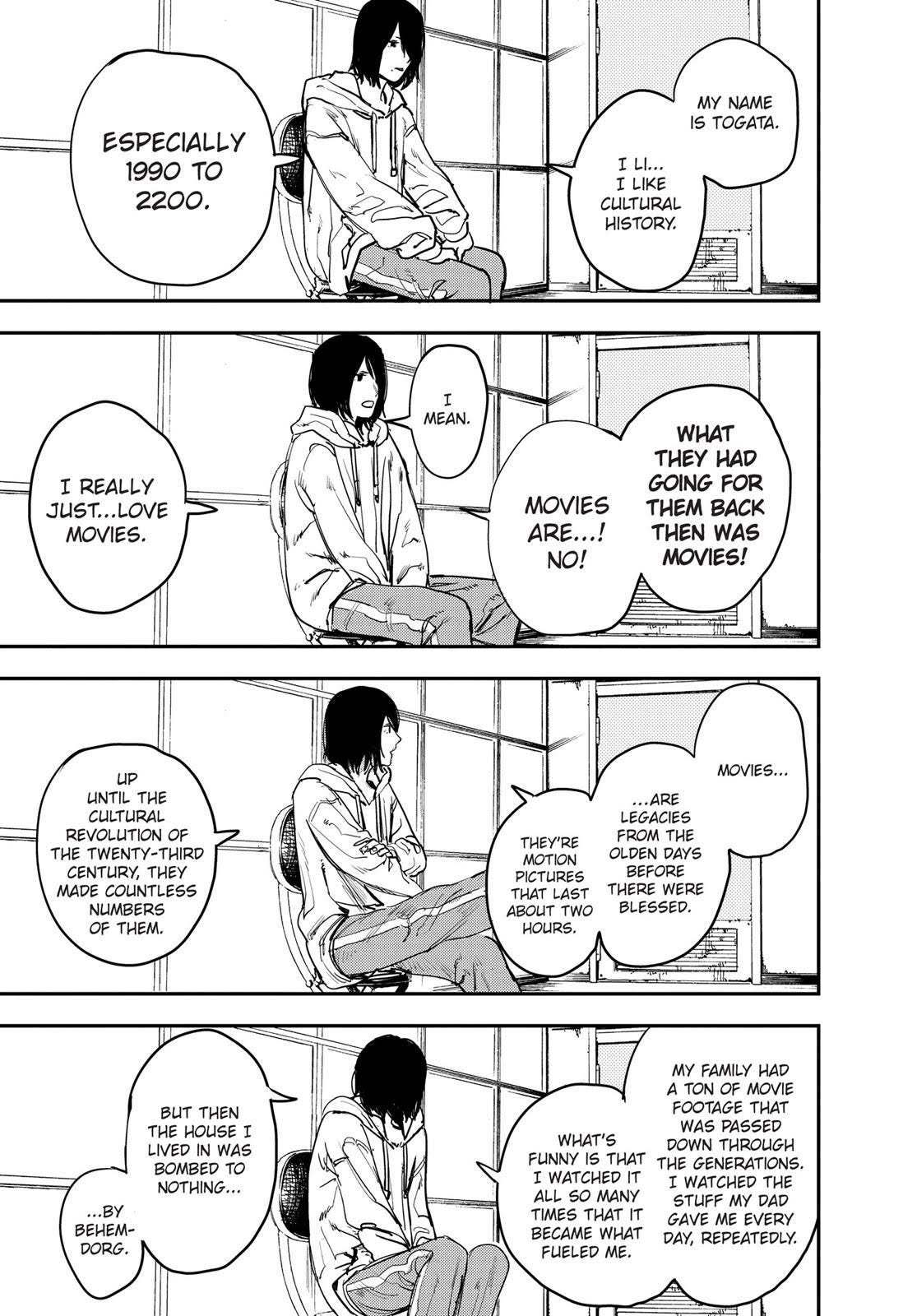

At the end of Fire Punch’s first volume, Fujimoto introduces the character Togata.

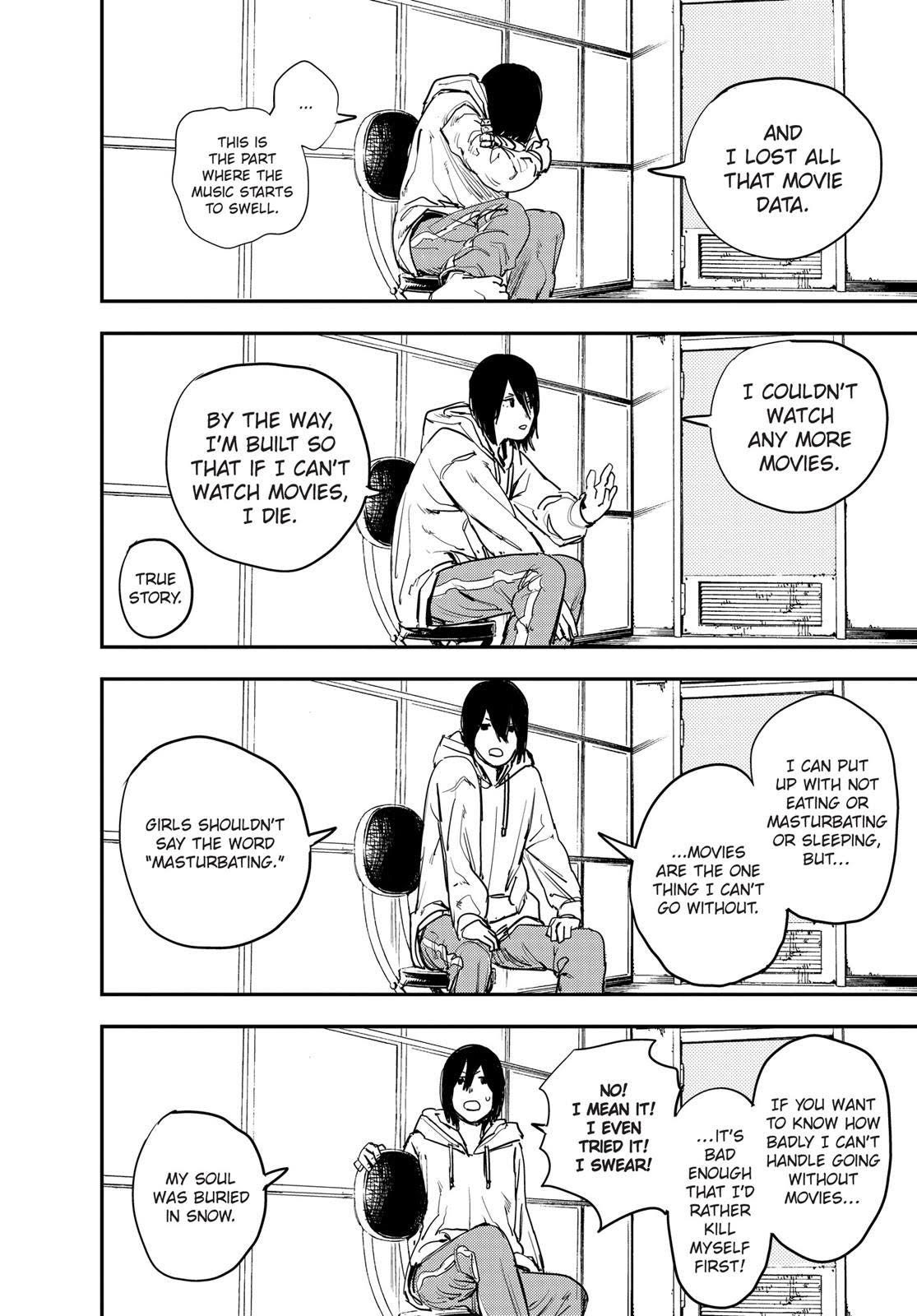

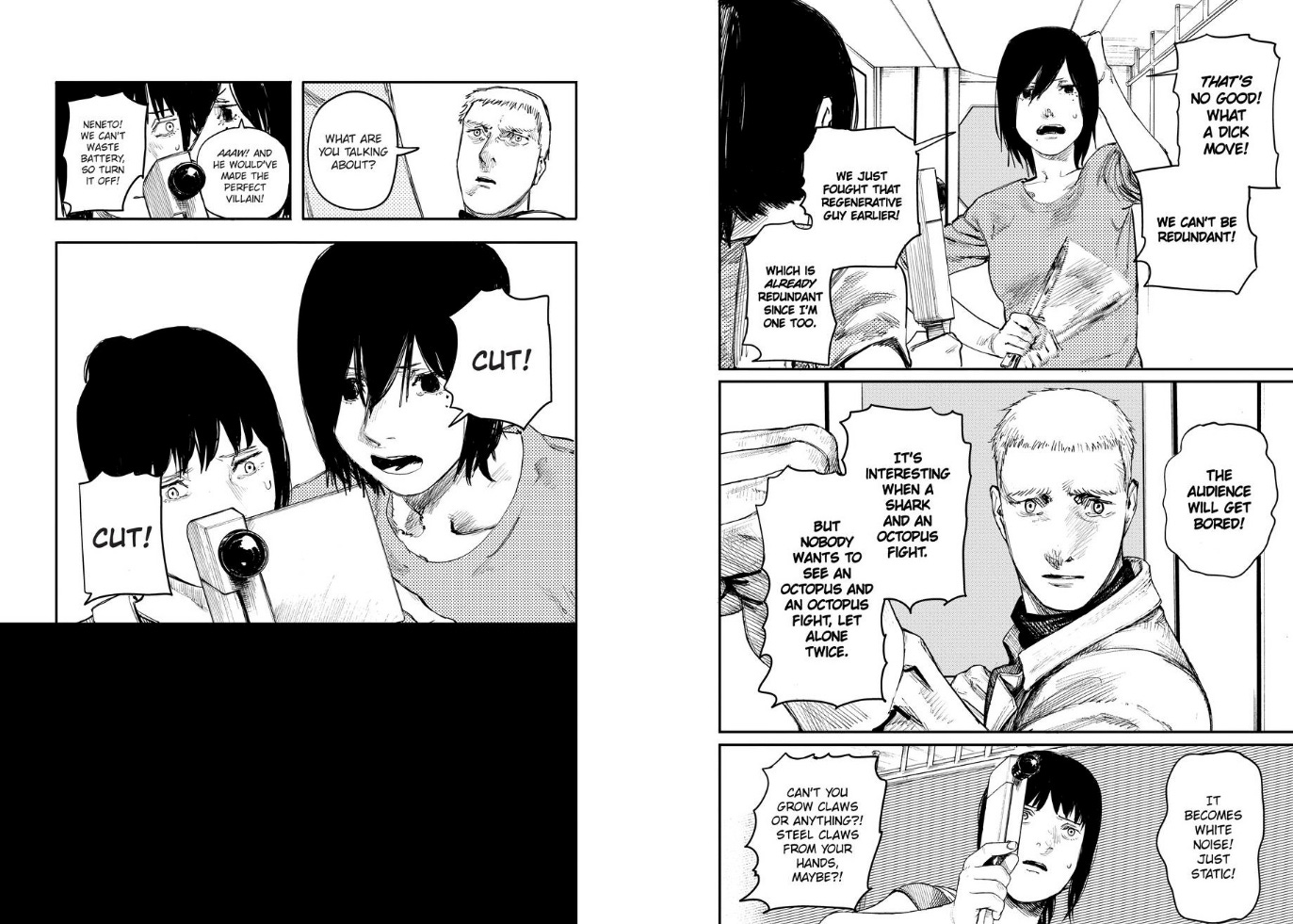

Togata begins to follow and film Agni, stating his confrontations with opponents and assisting both him and his adversaries. Fujimoto uses a formal conceit that resembles a found footage film, where Togata will instruct her camerawoman to “cut” and excluding parts of the narrative from being included in the manga’s pages.

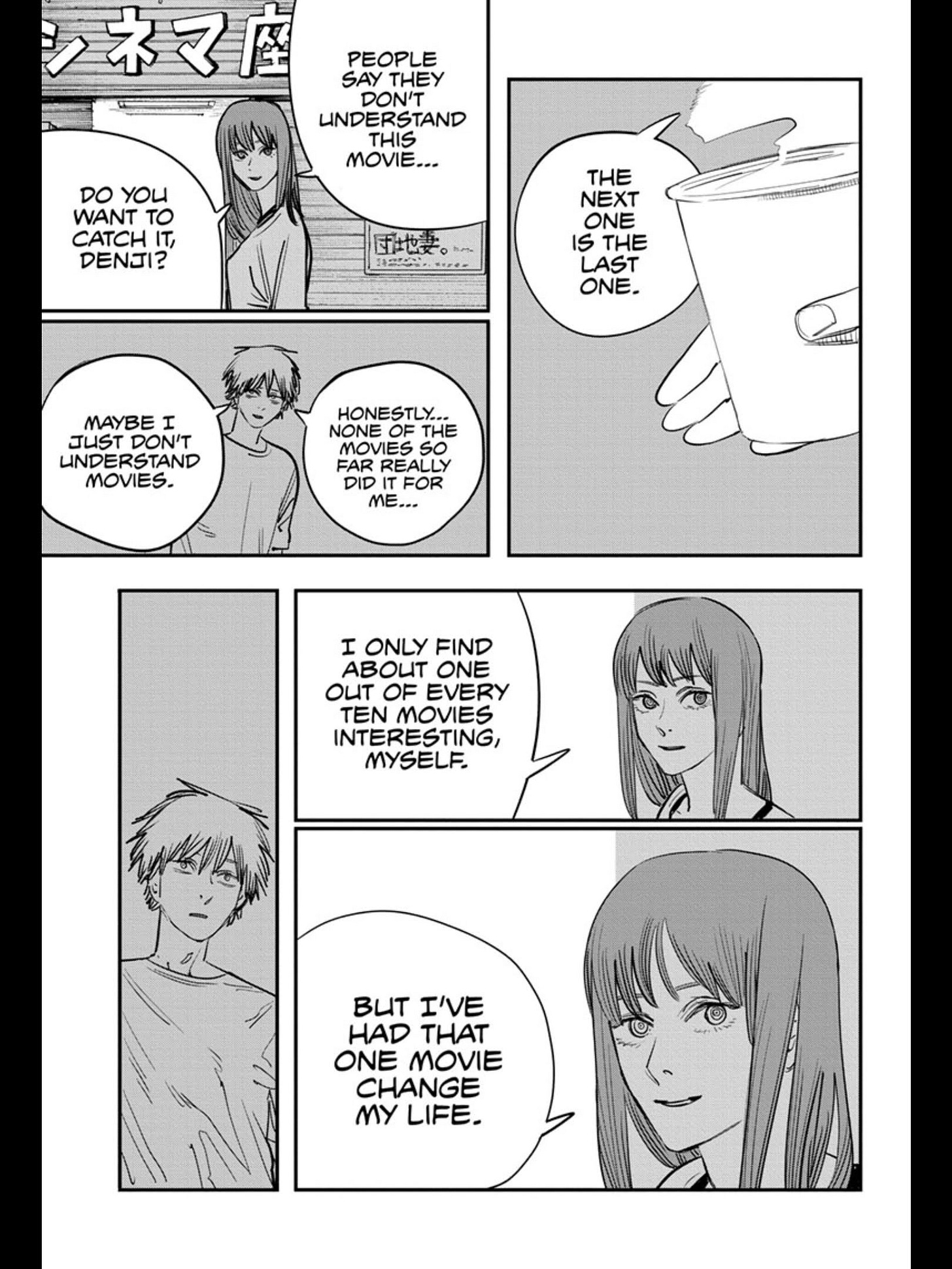

Togata also repeatedly makes reference to films the audience would recognize, including Dead Alive (1992), Star Wars (1977), Home Alone (1990), Spider-Man (2002), and The Matrix (1999). Fujimoto takes film seriously as a medium in both Fire Punch and Chainsaw Man.

Strip everything worthwhile from both manga, and the self-aware references to cinema would keep me engaged. Across Fire Punch and Chainsaw Man, Fujimoto has developed terrifying, nihilistic worlds where the greatest solace comes from art. Fire Punch is a manga about making movies and the costs of commitment to one’s art. Chainsaw Man explores a character who can’t muster this kind of zealous commitment to anything but his own satisfaction, though he can’t fully grasp what satisfies him. This kind of subjectivity is the foundation of the kind of characters we see in Fire Punch and more conventional shounen manga. Denji and Togata exist on the same continuum, where bodily satisfaction becomes sublimated into an artistic endeavor with a vice grip on one’s soul.

I have more to read of both Fire Punch and Chainsaw Man, but I’ll be seated for the Reze Arc movie. I imagine Fujimoto is gratified yet again2 to see his work on the big screen.

Weekly Reading List

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23311886.2025.2562379 — I am back in peer reviewed form. This open access, collaborative journal article for Cogent Social Sciences poses the question: “What does it mean to psychoanalyse sport?”

Event Calendar: Darren Aronofsky Will Never Know Peace

Perfect Blue (1998) is back in theaters this week. Along with that, I added some notable releases coming to megaplexes this October. Unfortunately we still have another month and a half until Running Man (2025) comes out, meaning corporate theater audiences will continue to be punished by that same trailer they’ve been running for what feels like forever.

Until next time.

Since picking up the manga again, I’m on chapter 198 and enjoying it well enough.

His one-shot Look Back (2021) was adapted into a film in 2024.

I am for structure purist + content neutral for my pick this week.