Issue #409: The Smiles and Cries of Training Day

Not everyone follows newly released music as closely as I do. For some of my friends, it can be a challenge to even name one new release that they enjoyed in a given year.

Everyone had to meet that challenge for last week’s Music League category. I submitted a song from Yuno Miles’s ALBUM. I hope to write more about it next week. We also had some usual suspects like Sulfuric Cautery and RXKNewphew. I heard The Lemon Twigs for the first time on this playlist. Key Glock’s “A+” underperformed; it’s a truly excellent song.

This week, a long overdue piece on Training Day (2001).

“You’re in the office, baby”: Dirty Work and Desublimation in Antoine Fuqua’s Training Day

During Thanksgiving week, I saw Training Day (2001) twice. Once at Coolidge, my first time seeing it on the big screen, and once at home with Antoine Fuqua’s commentary. That’s besides the five or so times I’d seen it before. It’s one of my favorite films of all time. Writing about Training Day has been something of a white whale. I’ve never quite been able to figure out what I want to get across about this film. I figured these rewatches might afford me the opportunity.

“Believe it or not, I do try to do some good in the community”

There are plenty of points of historical significance. Though Ethan Hawke may have proven himself as an adult leading man in Before Sunrise (1995), Gattaca (1997), and Snow Falling on Cedars (1999), Training Day propelled him to the profile he enjoys today. Denzel Washington won his second Oscar for the film, and his first for Best Actor after an unjust loss in 1993 and a more debatable loss in 2000. As Fuqua says on his commentary track, Training Day used a certain ethnographic filmmaking mode. He refers repeatedly to the meetings and “hanging out” with various criminal elements and law enforcement officers. He approached the direction of Washington’s Alonzo Harris as an undercover cop, though non-motor pool vehicles and street clothes are common for detectives today. Indeed, what Alonzo really is is corrupt, with screenwriter David Ayer taking inspiration from Rafael Pérez. Pérez’s career is notorious, with one of the most scandalous allegations being his killing of Biggie Smalls on behalf of Suge Knight.

This aspiration toward realism extends to the film’s personnel. Cle “Bone” Shaheed Sloan, a former street gang member, served as Training Day’s technical advisor. He also played a fictionalized version of himself, one who was never recruited to work on or act in a Hollywood film. Sloan worked to negotiate with the community to film in Los Angeles neighborhoods like the Imperial Courts and The Jungle. Fuqua also attributes his desire for cinematic verisimilitude to a sense of altruism, interacting with children who live in these neighborhoods in the course of filming. One of his success stories from this endeavor is Malcolm Mays, who was an extra on Training Day and went on to work with Fuqua again many years later on Southpaw (2015).

But you can find all this stuff on Wikipedia or the IMDb trivia page. I hold myself to a higher standard.

Crime and Crime and Punishment

What is Training Day, really, aside from a gritty actor’s proving ground loosely adapting the LAPD’s ill repute? Coming to an understanding like this starts and ends with Alonzo Harris. Washington says, “[H]e’s done his job too well. He’s learned how to manipulate, how to push the line further, and in the process, he’s become more hard-core than the guys he’s chasing.” In the director’s commentary, Fuqua is clear in establishing that Harris’s attitude about crime — “it takes a wolf to catch a wolf” — is earnest. But he also repeatedly describes Harris as the devil and characterizes his relationship with Hawke’s Jake Hoyt as Faustian. Hoyt, says Fuqua, has the tragic flaw of ambition. He points to the line early in the film where Hoyt says, “You should see those guys’ houses,” referring to LAPD division leaders. That line also reveals something else: corruption that is endemic to the order of Law. This is Training Day’s most enduring message: criminality is a feature, not a bug, of law enforcement. This excluded and covered over element of crime is necessary for the functioning of society’s Law as such.

I’ve explored this idea in conjunction with other films, such as Key Largo (1948). Johnny Rocco’s (Edward G. Robinson) monologue remains the most compelling treatise on the subject, delivered while he plays out a scene from Benito Cereno (1855):

So I won’t get away with it, huh? How many times I heard that from dumb coppers I couldn’t count ... You’d give your left eye to nail me, wouldn’t ya, huh? Ha, ha. You can see the headlines, can’t ya? ‘Local Deputy Captured Johnny Rocco’. Your picture’d be in all the papers. You might even get to tell in the newsreel how you pulled if off. Yeah. Well listen, hick, I was too much for any big city police force to handle. They tried but they couldn’t. It took the United States Government to pin a rap on me. Yeah, and they won’t make it stick. Why, you hick, I’ll be back pulling strings to get guys elected mayor and governor before you ever get a ten buck raise. Yeah. How many of those guys in office owe everything to me? I made them. Yeah, I made ‘em, just like a tailor makes a suit of clothes. I take a nobody, see? Teach him what to say, get his name in the papers. I pay for his campaign expenses. Dish out a lotta groceries and coal, get my boys to bring the voters out, and then count the votes over and over again till they added up right, and he was elected. Yeah. And what happens? Did he remember when the going got tough, when the heat was on? No, he didn’t wanna. All he wanted was to save his own dirty neck ... Yeah. ‘Public Enemy,’ he calls me! Me, who gave him his ‘Public’ all wrapped up with a fancy bow on it!

One might read Rocco here as lamenting the disloyalty of those whom he supported. But this monologue also reveals the hidden how, the mechanics of how normal social life and governance are inextricably connected to crime. Other than politicans’ need of money, there is less to account for the why. That’s where Detective Harris and Training Day come in fifty years later:

Shit, they build jails cause of me! Judges have handed out over 15,000 man-years of incarceration time based on my investigations, okay? My record speaks for itself. How many felons have you collared?

In the most cynical view, judges elected through the machinations of the Johnny Roccos of the world are handing out centuries of incarceration time based on the investigations of the Alonzo Harrises. But there’s more in Harris’s brief excoriation of Hoyt. He looks at the results of his police work in terms of “man-years of incarceration,” a strangely abstract view of his record that prevents “school kids and moms, family men” from catching “stray bullets in the noodle.” This body of work rendered in man-years seems intuitively impressive, though, despite having nothing against which to measure it other than the average length of a human life (15,000 divided by 73 is about 205). Harris’s assertion, and genuine belief, is that his methods are necessary for his results. Crime and punishment on one side, together, rather than opposite each other.

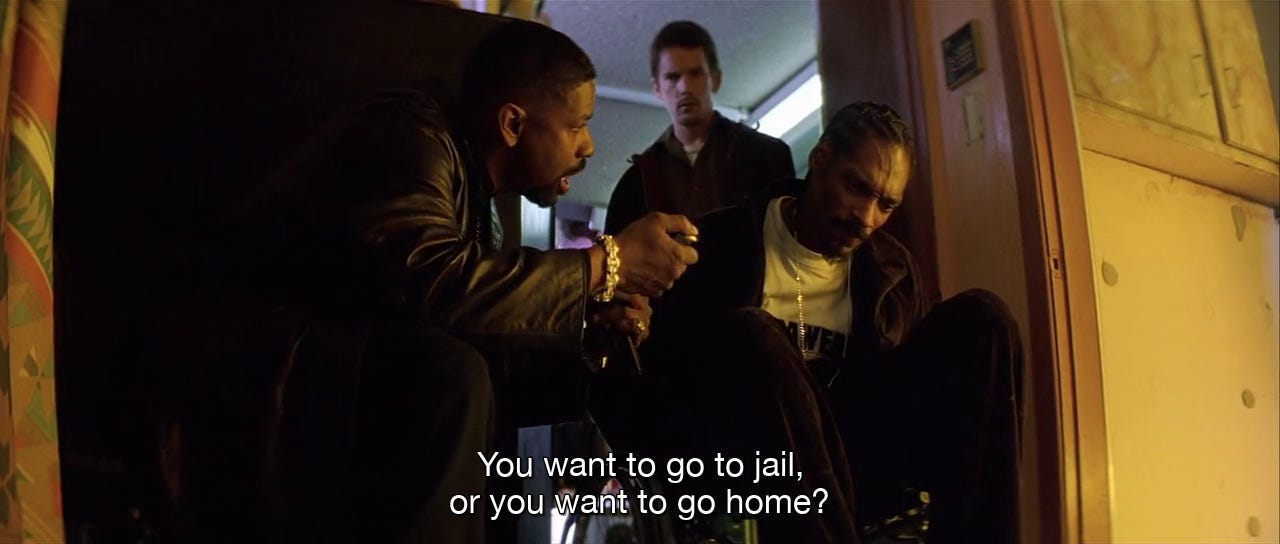

“Do you want to go to jail or do you want to go home?”

Film theorist Jared Sexton reads neither Fuqua’s mission of social uplift nor the codependence of criminality and Law into Training Day. In Black Masculinity and the Cinema of Policing’s (2017) first chapter, Sexton is disinterested in the material conditions of the film’s production and Fuqua’s stated dual motives of verisimilitude and humanitarianism. Instead, Training Day is a case study of the complex dynamics of Black representation in popular culture and politics:

[S]uch convergence [of President Barack Obama’s election compared to “conditions of segregation that characterize black existence in the USA over the same period”] complicates the current thinking about an institutionalized black complicity with the structures of white supremacy, especially in the immediate aftermath of 9/11. These various guises of black empowerment should not be simply contrasted with the associations of violence, dispossession and illegitimacy that seem to otherwise monopolize the signification of racial blackness. Rather, the former should be understood as an extension of the latter. (4)

According to Sexton, then, the disparity between the kind and place of representation (’positive,’ presidential) and the failure of Black American life to improve proportionally is, in fact, not a mystery. Nor is each condition driven by distinct social forces. Instead, Sexton argues that these modes of representation are in service of continued concrete, exigent marginalization of Black Americans.

This chapter is one of the few academic treatments of Training Day, and Sexton’s overall argument is convincing, although I take issue with a few points. Even with the incisive close readings in the chapter’s latter half, Sexton’s argument is primarily sociological and meta-textual, focused on Training Day’s position as a cultural and market product. There is also extensive meditation on the Oscar wins of Denzel Washington and Halle Berry, the vicissitudes of directing-while-Black, and an illustrative genealogy from In the Heat of the Night (1967) to Training Day.

The most vital dimensions of Sexton’s critique extract from the film the structure of antiblackness, “a series of forced choices … do you want to go home or do you want to go to jail [sic]”1 (17). From Sexton’s perspective, Training Day un-self-awarely manifests the absolute, systemic capture of Black subjectivity, “Where, exactly, is home, we might ask, if you are black in the contemporary world?” (17). In part, this is through Alonzo Harris himself, whose day out with Hoyt “suggest[s] the mortal dangers of cross-racial fraternity” (21) and “racial[ly] code[s] state violence as black and [combines] such black state violence with offenses in the register of conventional Christian morality” (26).

These ideas come together, according to Sexton, in Harris’s final comparison of himself to King Kong. Sexton writes, “One could hardly anticipate that any director could get the most celebrated black actor of the late twentieth century—the perennial good guy—to compare himself onscreen to the archetypical figure of the ‘historical tendency [in Western culture] [sic] to identify blacks with ape-like creatures’ (28). Sexton’s final words for the film are exacting:

As for Washington’s historic Academy Award and the distinction afforded Fuqua in the process, it appears to be something more than Pyrrhic victory. It betrays the scent of a con, a black cinematic event released into custody, produced and distributed under conditions of cultural parole … parole names not the release from prison into unalloyed freedom—if only the prison house of Hollywood’s dream work—but rather continued regulation amid the foreboding sense of recapture. (31)

Just as the film attempts to flatten difference between the professional actor and gang member through its casting and filming, this traffics the greater and more enduring obscenity that Sexton draws out in his argument.

“I’m sorry I exposed you to it, but it is”

While Sexton is spot-on in his analysis of Training Day in some ways, he also diminishes the work as art and gives too little credit to Fuqua as a director. Fuqua is responsible for the aesthetic successes of the film as much as he is responsible for its political failures. Sexton proceeds with a view of Hollywood filmmaking that evacuates the director of any agency, “Directors may call the shots, but film editors and financial underwriters with pending distribution deals and potential consumer markets in mind always have the first and final word” (15). This belief is an inheritance from Horkheimer and Adorno, the originators of the formulation of “culture industry,” but Sexton’s view is what I call a naïve cynicism regarding film production.

It is a matter of fact that there are regularly Hollywood productions where the director retains final cut, managing to have the last official word on a film’s content as an art object. I attribute this to the disinterest in or misunderstanding of film that a financier may have. A studio executive is rarely the person best suited to make a profitable film, and sometimes they even know it. This is where the filmmaker’s agency is most evident.

Evacuating the filmmaker of their control makes Hollywood much easier to understand. A film exists only as a vehicle for ideology and as a commodity to maximize revenue. What I think is true, and also more interesting, is that the filmmaker makes many meaningful decisions when producing a film regardless of whether it is independent or studio backed. However, the glut of ideological film (every big budget film, until proven otherwise) shows how deeply entrenched artists are in this expression of ideas. As a result, the filmmaker’s own agency is interpellated and instrumentalized without the studio having to lift a finger.

One might consider how Training Day is a reactionary film in the same, routine sense as Hollywood cinema and how it is exceptional in its promulgation of, say, antiblackness. Fuqua’s film is not unusual in its ultimate endorsement of the proverbial “good cop” who triumph’s over the “bad apples.” Sexton writes of the near-final scene where Bone tells Jake, “We got your back”:

The communal hatred of this particular black cop—the others in the film are no better—overrides a general and otherwise healthy skepticism toward the political functions of the police as such. This hatred runs so deep, in fact, as to encourage their active and reckless backing of a “whitened” cop who will return, as per job description, to violent many among their ranks in a scenario inadequately described as self-incrimination. (26)

Of course, Sexton is intentionally reading the film against the grain here. What Fuqua presents, and Sexton disputes, is the idea of the “criminal neighborhood”2 as capable of self-regulating homeostasis and Hoyt as the benevolent police officer who lets the neighborhood flourish under his watch rather than languish under his boot (31).

“It’s all about smiles and cries”

If the bargain that Harris presents to Hoyt is Faustian, it mirrors what Hollywood films ask of their audience in exchange for their pleasure. One might uncritically receive a film’s overt message without attention to the sinister underside. Or one might, as I do, encounter some derivative of jouissance through the mutual acknowledgement of a film’s formal features and the insidious ideology it transmits. Both are deals with the studio devil.

Ironically, Sexton’s condemnation of Fuqua’s “image-track of urban fear and loathing” (22) aligns him with the studio executives, who, according to Fuqua’s account in the film’s director’s commentary, objected to the film’s ‘gritty’ presentation of ‘the streets.’ From Fuqua’s perspective, Training Day represents an unfiltered, unsanitized version of life in some LA neighborhoods. It is remarkable, then, just how much of the film is dedicated to conversations between Hawke and Washington in frames that are dominated by their visages in close-up.

Much like the pledges of realism by David Simon on behalf of The Wire (2002), Training Day’s supposed realism presents the switch point between obscenity and enjoyment precisely through offering a window for one to enjoy the obscene. Sexton points to the evident similarity of Apocalypse Now (1979) and Training Day, faulting Fuqua’s film for failing to respond to the age old critiques of Heart of Darkness (1899) (28). Like Heart of Darkness, Training Day is a travelogue, analogizing Hoyt’s exploration of The Jungle and the Imperial Courts to a descent into hell. This is hardly an ennobling representation of these neighborhoods and their residents. But what Fuqua never fails to acknowledge is that Hoyt is already in hell, whether he knows it or not. His dedication to law enforcement is complicity in the corruption that facilitates the enormous houses of the division leaders.

Likewise, his domestic life as a father is no more dignified. A throwaway line from Hoyt’s wife, Lisa (Charlotte Ayanna) is rich as she “moos” at her husband while breastfeeding their child, one of the film’s overtures to the complex gender politics primarily explored through Hoyt and Harris. Early in the film, Harris delivers a rapid-fire provocation to Hoyt not in Ayer’s original script:

You do have a dick, don’t you? … Okay, your dick lines up straight like that, right? To the right of it and to the left of it are pockets, right? In those pockets are money. Look in either one of them, pay the bill.

This exchange is an early indicator of the film’s greatness and a signal of its less obvious symbolic preoccupations. Though Hoyt may be imperiled in the film as the victim of Harris’s machinations, expressed in the film’s form through a labyrinthine plot filled with devices and details that transform from insignificant to significant, Hoyt is never free of the vicissitudes of his own desire. This is a desire that strains him between notoriety and obscurity, man and woman, lawfulness and criminality, smiles and cries. What Hoyt should learn after his odyssey, above all else, is that these are not poles, but horseshoes. A thing contains always what it attests to oppose. Fuqua does not exalt what he films, he desublimates the admired roles of police officer, father, and man to hellish conscriptions.

Weekly Reading List

https://letterboxd.com/journal/letterboxd-video-store-unreleased-gems-december-2025/ — The Letterboxd Video Store is coming and there’s nothing we can do to stop it. At least the premiere films sound good.

Event Calendar: Sorry, I’m going to a movie

No updates today because I need to get to my advanced screening of No Other Choice (2025). But the list is getting pretty thin. I’ll try to beef it up next week. Feel free to send submissions.

Until next time.

There’s an obvious difference in the quality of the expression as Sexton misquotes Harris, reversing “home” and “jail.”

I hate to use this phrase without qualification, but I think it is fair to say that Training Day presents certain parts of Los Angeles as in a state of exception with regard to Law. Regardless, one should ask what exactly constitutes such a neighborhood, and what features does Fuqua use to represent it?