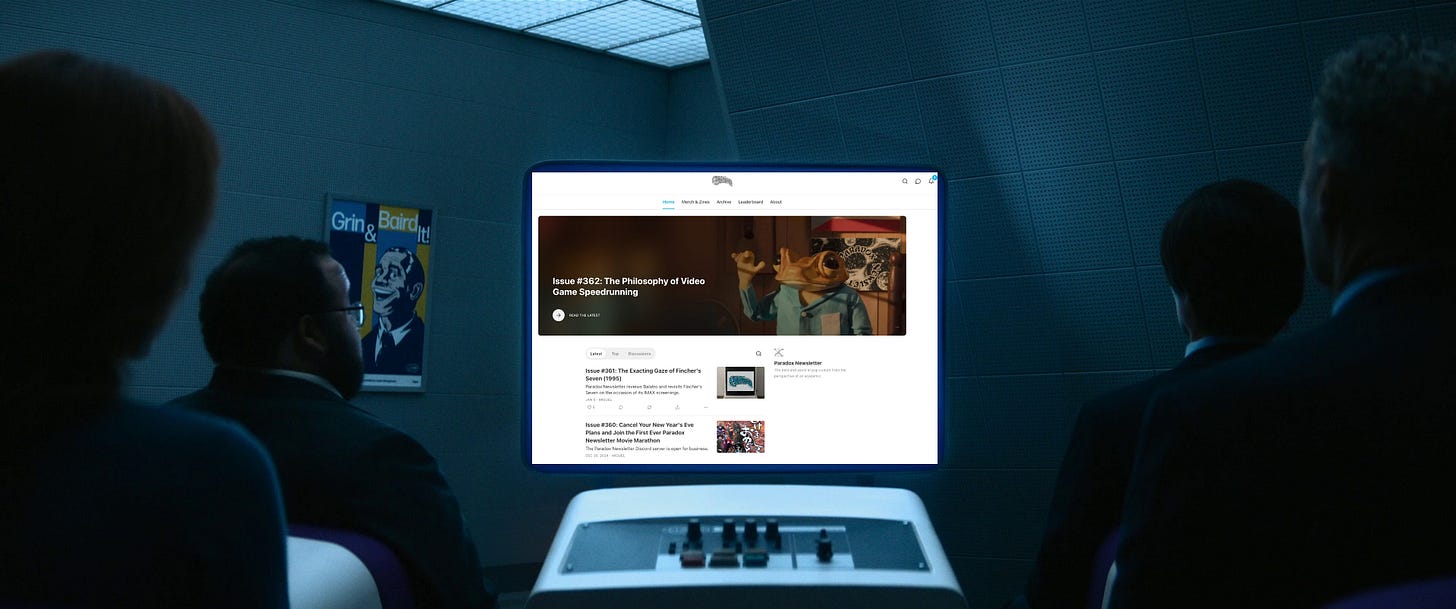

Issue #363: Severance Has the Secret to Being Happy at Work

Writing about Severance is undignified. There’s nothing about the show itself that makes it that way. Excluding these examples, I had to write the word “outie” eleven times and “innie” seventeen times to discuss the show in its own vernacular. I find this profoundly irritating and, if I write about Severance again, will need to come up…