Issue #369: The Oscar Goes to GQuuuuuuX

The Oscars are my Super Bowl. I love watching them every year, even though I usually hate the aspects of film they venerate. I was pulling for The Substance (2024). As soon as it won for Best Makeup and Hairstyling, I knew it was a wrap. A consolation prize portending another award season travesty. Anora (2024), I’m sure, is a fine film (I didn’t see it), but the overall suite of contenders in these 97th Oscars give a much clearer picture of just how bad 2024 was for film.

This is especially striking compared to the 96th Oscars, with one of the most competitive Best Picture races in history. That award season was packed with amazing films. This year? Not so much.

My favorite movie of the year, Mobile Suit Gundam GQuuuuuuX: Beginning (2025), won’t make next year’s Oscars. I know it is my favorite movie of the year because I love Gundam. And I think GQuuuuuuX is a work that is going to re-present what is great about the original series. More about that below.

I also have my usual, heady Severance recap. This one is pretty similar in scope to last week’s. That makes me happy. Maybe it makes you happy too.

New to the letter, a Spotify playlist, accompanied with some commentary on recent and not so recent pop music. What can I say? Paradox Newsletter has it all.

The Radical Incompleteness and Fallibility of Absolutely Everything in “Chikhai Bardo”

James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) famously ends with a chapter from the perspective of Molly Bloom, Harold’s wife. In a long series of words, she gets the final one: “Yes.” “Chikhai Bardo” isn’t the last episode of Severance (2022) or even the last episode of the season. But having an episode with a focus on Gemma’s (Dichen Lachman) perspective serves some important narrative purposes — different from Ulysses’s “Penelope.” The audience did not understand the stakes of the relationship between Mark (Adam Scott) and Gemma Scout. Mark is mournful after her death, his suffering one of the dominant affects of the series. Gemma as Gemma, and not Ms. Casey, is entirely absent from the episodes before “Chikhai Bardo.” In this gut punch of an episode, Severance shows what is has up until now been only telling. Mark Scout does not just yearn for Gemma as a lost object. Gemma and Mark are in love and equally motivated to reunite.

There is also something to be said, like Ulysses, for privileging the point of view of Gemma. Some morbid theories of her relationship to Mark have cast him in the role of Tim from Braid (2008). In the Jonathan Blow designed game, the player, as Tim, is ostensibly a benevolent liberator of an imprisoned princess, confined to a castle — an homage to the plot of Super Mario Bros. (1985). The game’s final twist, however, is that Tim is in fact an evil pursuer who has tormented her. Mark is neither Gemma’s tormentor nor her jailer. That role falls solidly to Lumon and helps the audience better understand the ethical dimension of Severance. Mark and Gemma are our heroes and Lumon is unquestionably the villain, although perhaps there will be a sympathetic justification for their unequivocal wrongdoing. In this way, “Chikhai Bardo” is a structurally similar reversal of “Penelope,” who gives voice to Molly Bloom to complicate the moral positions of Ulysses’s characters.

But what I have in front of me to interpret in “Chikhai Bardo” is only worth interpreting because it is what Severance always is: masterfully crafted. Aligning the audience’s sympathies with Gemma and Mark in this very emotive fashion is appropriate for a show that has commanded attention without melodrama. Jessica Lee Gangé’s first turn in the director’s chair makes for perhaps the show’s best episode yet. There are unusual camera effects that take us through fiberoptic cable, a bright and cheerful visual language that speaks in ways Severance never has before, a contrasting color grade and visual filter that delivers that optimistic affect as well as evokes celluloid. This is Severance at another level. Gagné creates a character, Gemma, essentially in the span of fifty minutes, who seems like she’s been part of the narrative the whole time. More than that, she makes a genuinely compelling and tragic romance story with the help of a monumental performance from Dichen Lachman and Adam Scott delivering lines like “there’s a kid that’s out there just waiting for us. Just got to reach out and grab her,” with unimaginable conviction.

My praise for the episode might seem extreme. But I felt something watching it. Despite the complexity of the plot elements the episode introduced, it is Severance’s most simple and self-contained episode to date. It even mocks the show’s complexity through Devon (Jen Tullock), “I can tell you’re smarter than me,” and Gemma, “can you please just talk like a normal person?”

Travelers

The episode is bookended by a question: “where did you go?” Nurse Cecily (Sandra Bernhard) poses it to Gemma at the beginning of the episode and Devon to Mark at the end.

Between the two questions, Reghabi (Karen Aldridge) says Mark is “journeying.”

This departure by Gemma and Mark away from their corporeal bodies and into their memories structures the episode. The flashbacks are their mutual reminiscence. It adds to the romance of the episode. Both of their answers to the question “where did you go?” are the same.

By structuring the episode using this conceit, “Chikhai Bardo” reinforces a thematic concern about the relationship between the psyche and the body. Previously, I have talked about how Severance interrogates a brute-physical view of personal identity. The severed innie and outie versions of a personality are the same person, the same subject. This is, at least, Lumon’s party line. A person’s body, physical experience and measurable biological stimuli are what make someone who they are. In the series premiere, “Good News About Hell,” Mark explains at Ricken’s (Michael Chernus) “dinner” party, “Well, there is no other one. It’s me. I do the job.”

The show does a lot to show how this view is at least reasonable, even if it stops short of endorsing it. (Also, making it the viewpoint of an evil corporation does a lot to undercut it without needing to argue against it). Gemma’s teeth and hands hurt when she exits the various severed rooms in which she is subjected to all manner of quotidian and exceptional horrors. But “Chikhai Bardo’s” memory-journeying is one big subversion. These memories are what make Mark and Gemma, and emphatically make Mark and Gemma as a couple. Their connection seems to be the negative image of the connection between Mark S and Helly R (Britt Lower). In every way Helly R and Mark S’s relationship is partitioned, following the logic of the Lacanian non-relation, Mark Scout and Gemma seem to have the unmediated relation through some metaphysical realm. The complexity is, of course, they are separated by an impossible physical barrier, the “severance barrier” that keeps Gemma sequestered on a sub-sub basement of Lumon that she cannot escape.

“Talk of blood is as sticky and slippery as the substance itself.”

Bodies do seem to have some immanent, measurable quality in Severance. The fact that there are bodies, as opposed to just cosmic clouds of consciousness or “grey and formless mist, pulsing slowly as if with inchoate life” (Looking Awry 14), is mysterious and important. The body is measured in all manner of ways in Severance, but most insistently through the blood in “Chikhai Bardo.” Gemma gives blood at a drive at Ganz College, has it taken from her in the course of her observation at Lumon, and the sub-sub-basement severed torture doors open through blood verification.

Through Gemma’s medical journey that seems to begin with her blood donation and end with her imprisonment by Lumon, the corporation has been involved in every step. Lumon administered the blood drive as well as ran the fertility clinic in which we see Lumon corporate logos and the appalling Dr. Mauer (Robby Benson) walking down a hallway.

Though blood is important for medical assessment, cases where blood has been used to determine who a person is have a fraught history. In the United States, it harkens back to the “one drop rule” used to racially categorize Black Americans or the measurement of blood quantum to determine indigeneity and specifically Indian tribal membership. Despite these institutional (hegemonic) uses, blood is not a very good standard for determining (and enforcing) identitarian details about a person.

Race is a social construct legible primarily because of one’s appearance. As a result, one’s blood has very little that can, in a vacuum, communicate anything about one’s race. Karen E. Fields and Barbara J. Fields write in Racecraft (2012):

[B]lood made in society by human beings has properties that nature knows nothing about. It can consecrate and purify; it can also profane and pollute. It can define a community and police the borders thereof. Natural blood never does that sort of thing: it only sustains biological functioning. (41)

To whatever extent blood comes to represent DNA, a relationship the Fields sisters complicate in Racecraft, even our contemporary direct-to-consumer ancestry tests only determine how similar one’s DNA is to a control group with “known ancestry.” When someone says they are “6% Romanian” because of their 23andMe, the information they actually received is that 6% of their chromosomes most closely resembled the chromosomes of people who told 23andMe they are Romanian. The seeming importance of blood to Lumon’s targeting of Gemma and Mark places us in the realm of both science fiction and pseudoscience — perfect for a company whose real life namesake, Samuel Kier, sold petroleum as a medicinal tonic.

“Moreover, each of you is, de jure, a Buddha”

Critical to Severance, and this episode in particular, is the tension between science and religion. We can see in the example of blood and direct-to-consumer DNA tests that supposedly scientific processes are underwritten by an ideological framework. These fundamental assumptions turn science into something spurious and insidious. But Lumon is nothing if not both, attracting Gemma through a mail marketing scheme that resembles the Art Instruction Schools qualification test scam (thanks to reddit user PhoebeAnnMoses for making this connection). Gemma shows Mark a card that supposedly represents “chikhai bardo,” one of six stages in the cycle of life, death, and reincarnation according to Tibetan Buddhism.

Gemma says, “it’s the same guy fighting himself, defeating his own psyche. Ego death” to which Mark replies, “How do you know it’s the same guy?” It is the similarity of the hair, according to Gemma, that makes her certain.

It’s no accident that the episode takes its title from this fourth of the six bardos. This inclusion suggests a lot about the plot and Lumon’s plan, pushing the audience’s mind to the topic of reincarnation and subjective dissolution in the moment of death. The remains of the body may be more important to Lumon’s plan, however. But for me, this was the first time I considered the possibility that Lumon’s goal has nothing to do with the body at all and everything to do with some kind of desubjectivized collective consciousness — the promise of human instrumentality or even East and Central Asian Buddhism.

The Tathāgatagarbha sūtras suggest that every sentient being can achieve Buddhahood through the cycle of reincarnation. Because Severance is a work more concerned with philosophical ideas rather than theological rigor, I believe we can read various Buddhist traditions loosely and together to have the richest understanding of the text. The evocation of the ego death required in the stage of chikhai bardo opens up the possibility to the ascendence to a state of enlightenment that would annihilate the subject as such and open them up to a different manner of collective existence. If the part about subjective annihilation sounds similar to Lacanian jouissance, that’s no accident either.

In Seminar X: Anxiety (2004), Lacan writes extensively about his study of Buddhism undertaken in Japan. Notably, he follows the premise of the Tathāgatagarbha sūtras that everyone has the possibility of ascending to Buddhahood:

Moreover, each of you is, de jure, a Buddha — de jure because, for particular reasons, you might have been cast into this world with some handicap that will create a more or less insurmountable obstacle to this point of access. (Seminar X 224)

However, Lacan also notes the “handicap” that might represent an “insurmountable obstacle” to accessing the collectivity of Nirvāṇa. Though every subject’s endpoint is Nirvāṇa, there may be an eternal length of time separating a given subject from such a state. The insurmountable obstacle that prevents the subject from Nirvāṇa is, perhaps, human subjectivity itself.

Severance seems to make this reading available in its treatment of the human condition, particularly in “Goodbye, Mrs. Selvig.” Whatever Lumon is undertaking with the severance procedure and the tests Gemma undergoes may point to a form of ascendant consciousness that is at odds with the fallible human subject and all its foibles. Indeed, one imagines that a Lumon religious text might guarantee, de jure, a state of Kierdom to all who follow his teachings: a cure for mankind.

“All the things that used to be inside me, now they’re all outside”

Whatever transcendent possibility Lumon is aspiring toward, it seems woefully inadequate a justification for the torture Gemma’s many innies experience. Gemma’s severance appears to be a new kind, one that delivers a private hell to each of her substitutive consciousnesses. It is clear from the horrifying reaction of Gemma with entry to each new room that her suffering is uninterrupted and undifferentiated, with some version of her experiencing nothing but repeated dentist visits, another nothing but turbulent plane rides, and yet another tasked with writing endless thank you notes at Christmas.

A circumstance like this makes me wonder, yet again, what it means for the other versions of Gemma to not have any consciousness whatsoever except for when they are being subjected to a particular kind of torment. And make no mistake, this applies to the “outie” Gemma as well, consigned as she is to this subterranean circle of hell. The question of absence and presence, negativity and positivity, is crucial. Where something is, something else is not. We are clued into this paradigm by the question, “If you were caught in a mudslide, would you be more afraid of suffocating or drowning?

The crucial difference between the two is precisely of the negative against the positive. To suffocate is to have empty lungs completely divested of oxygen. To drown is to have those lungs filled with a substance that prevents them from receiving oxygen. The difference between being there and not being there is also the difference between a bodhisattva and a Buddha:

He would be completely and utterly a Buddha were he not there, but he is there, in this manifold form that took a great deal of trouble. These statues are merely the image of the trouble he takes to be there, there for you. (Seminar X 225)

Slightly earlier in the seminar, Lacan also paints a visceral picture of personal identity’s complexity:

If what is most me lies on the outside, not because I projected it there but because it was cut from me, the paths I shall take to retrieve it afford an altogether different variety. (Seminar X 223)

While the process of severance seems to entail not the divesting of the “me” that defines the subject but a infinite replication of it to confuse which is definitive and true, one cannot ignore the operative cutting of the severance procedure. There is also a question of the brute-physical facts of Gemma’s coming to be in Lumon’s clutches. If she was somehow revived through some science fiction contrivance that turns some part of her into the whole (the one whole as opposed to the many whole she now is), we are talking in terms of a something that defines the “me” being on the outside.

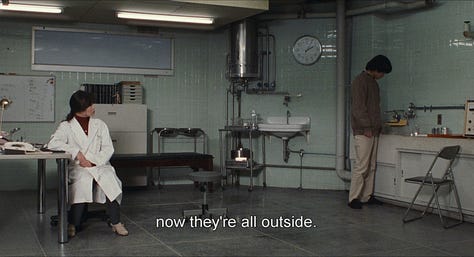

There is another work that gives a clearer sketch of the “altogether different” path Lacan must take to retrieve what is “most me” that lies outside of the subject, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure (1997). Kunio Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara) describes his subjective experience in nearly identical terms, “All the things that used to be inside me, now they’re all outside.”

As a result, Mamiya has no sense of his own identity. He has no recollection of who he is, nor is he able to even recognize himself in the mirror, as we see in the course of his interrogation.

Again, examining Mamiya as a contrast to Gemma or Mark, we are dealing with the paradigm of absence versus presence, lack versus excess. Mamiya is bereft of identity, Mark is in the process of trying to collapse two into one, and Gemma has as many as there are rooms on her special floor of Lumon. But Mamiya’s uncertainty invites us to question how Gemma knows anything about who she is at all. Her identity seems to be guaranteed by her memories. She is Gemma to the audience because we see those memories. But who is she really?

This is more than idle speculation about the provenance of her physical body in light of her apparent death. Severance has repeatedly posed the question of whether or not innies measure up to their outie counterparts. Are innies subjects? Are they people, with inalienable rights worthy of moral consideration? “Chikhai Bardo” turns the question toward the outies. What makes them who they are? Their body, their memories? What makes them anything at all?

Lumon, in some ways, seems to be scrambling to find something that will irrefutably evince the fact we exist at all. Or perhaps that is the endeavor of Severance as a work. Mark Scout or Gemma could, before the end of this series, look in a mirror as confused as Mamiya. Mamiya’s account of his own subjective experience emphasizes yet another Lacanian point:

[T]he eye is already a mirror … [I]t has no need of two mirrors standing opposite one another for the infinite reflections of a mirror palace to be created. As soon as there is an eye and a mirror, the infinite recursion of inter-reflected images is produced … The one image that is formed in the eye, the image you are able to see in the pupil, requires at the outset a correlate that is in no way an image. (Seminar X 223-224)

It’s not blood, but the eye that guarantees one is who they say they are. Both for the subject themselves, who looks at themselves to ensure their psyche is attached to the body they recall it being attached to last time they checked, and for others whose mode of recognizing the world is primarily visual. But the “eye test” isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. And it falls apart when one can’t tell apart the innie or the outie because they look the same, or is certain two people are the same simply because their hair is the same. For Severance, the fallibility of sight is connected to the mechanical function of the eye that Lacan describes. Images are reflected inside the retina courtesy of the light that enters through the pupil. The eye is a hole.

And it is every bit the generative hole that also exists in the back of Mark’s head, the one through which the severance chip was implanted and birthed a new Mark, Mark S.

“Mark will benefit from the world you’re siring”

The uncertainty about what guarantees the subject’s identity is an anxiety that permeates this episode. There are all kinds of examples of bungled speech and misunderstanding, hearing “ants” when Gemma said “plants,” her and Mark’s playful switching between “handy” and “handsy,” but even their misunderstandings fuel the romance the episode represents. Still, these are short circuits of a knowledge system that relies on sensory input. This sense-knowledge’s fallibility is ultimately irrelevant to their intersubjective connection.

But it is essential to an intrasubjective understanding of the self. A self that has long evacuated to cycle through another reincarnation in the case of a frozen body Ricken and Devon might have discovered on their Everest — sorry, Chomolungma — climb. We might draw a comparison between this morbid possibility and the actuality of Mark identifying Gemma’s body. Or, perhaps, the inability of Mark and Gemma to produce a body in a way that, pro-choice politics notwithstanding, has the tragic valence of a death. Mark and Gemma do ultimately become productive, if absent, parents to their infantile innies.

In both “Good News About Hell” and “Who Is Alive?”, we hear the Lumon innie orientation question “what is or was the color of your mother’s eyes?” It’s asked by Mark S to Helly R the first time and asked by Reghabi to Mark Scout the second time. Helly R can’t answer, emphasizing Helly’s severance from her outie’s memories and Mark Scout struggles to answer as a consequence of his ongoing reintegration. By an accident of DNA, though, Mark answers his own eye color, “brown.” Mothers and children can have the same eye color, after all. But this repeated situation demonstrates the ambiguity of the innies’ parentage.

This impression would fly in the face of Lumon’s narrative that positions the innies as an indelibly separate but vaguely connected substitute identity. Dr. Mauer’s sinister intimation that “maybe [Gemma] felt things behind those doors that [she] never felt with Mark” recalls Milchick’s assurance to Mark in “Goodbye, Mrs. Selvig,” “the solace you have given him down there will make its way to you.” Both are fantasies of the other jouissance, a misapprehension by a subject that another subject is able to experience the full, unmediated jouissance that is precisely antithetical to subjectivity itself.

This is the specious promise of Lumon itself, that their undertaking will somehow, someway, sequester from humanity the vicissitudes of life leaving behind only the undifferentiated pleasure that may or may not require the human subject to give up precisely that ambiguous thing that makes one human after all. Lumon’s quest seems to be both to find that something and excise it, to whatever end. And Dr. Mauer is telling the truth, though his statement doesn’t mean what he intends to imply. Instead of pleasure, Gemma has felt undifferentiated suffering behind the doors, a variety and degree of suffering Mark never put her through. The world that Lumon seems to want to sire is one where people doesn’t have custody of their own brains. Instead, Lumon will decide their fate.

Freedom and Interconnectivity in Mobile Suit Gundam GQuuuuuuX: Beginning

I don’t know what Hideaki Anno was thinking when he came up with the idea of Human Instrumentality for Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995). I don’t usually frame my readings that way, as what someone who made it was thinking. In Anno’s case, though, I’m curious. There are all kinds of cultural contexts you can read into the idea of Instrumentality — the union of all human subjects into one undifferentiated consciousness. Japan is a country that, relative to the United States, puts less emphasis on individualism. But Japanese society also individuates. People are separate, isolated, from one another in an enormous city like Tokyo, where Anno spent 1984 on. If Neon Genesis Evangelion were a show where Instrumentality was the desired outcome instead of the “bad end” of The End of Evangelion (1997), one might argue that a society, simultaneously isolating, yet discouraging of individual expression, could make instrumentality sounds very appealing. Finally, people are truly united.

Hideaki Anno isn’t the only person involved with Mobile Suit Gundam GQuuuuuuX (2025) but he is, by my measure, the most important person to be involved in it. My criteria is simply that his work as a writer for the series will be seen as an outsized influence on the final product compared to what he actually contributed. In fairness, the people with greater influence — Kazuya Tsurumaki, for instance — are heavily influenced by Anno. And that influence is clear in the through line from Mobile Suit Gundam (1979) to Neon Genesis Evangelion to GQuuuuuuX which will be seen, rightly or wrongly, as the synthesis of the two.

The switch point from one work to the next turns on a hinge that attaches two ideas together: instrumentality and Newtype. Sometimes, being a Newtype means being a space psychic. The most important narrative consequence of being a Newtype in a Gundam series is always combat prowess. The idea of the Newtype gets contrasted with the Force in Star Wars, with the Force that connects the Jedi and Sith similar to the connections Newtypes share. Yoshiyuki Tomino’s original vision for Newtype, I think, is not a precognitive space wizard. Instead, like the relation between the Jedi and the Sith, being a Newtype is about connection. In the plot of Mobile Suit Gundam, the Newtype evolved as a consequence of humanity’s travel to space — where people were born, lived, and died in gigantic orbiting space colonies called Sides. The capability that this evolution brings about is that of maintaining a strong connection among friends, family, and lovers separated by Earth’s atmosphere. Being a Newtype means you won’t forget your loved ones who move to space if you stay on Earth or vice versa. You’ll remember them. More than that, you will be able to reach them somehow. Because what a Newtype conquers is not the battlefield, but the seemingly insurmountable gap between human subjectivities. Existentialism awakens us to the horrifying impossibility of understanding someone else. A Newtype overcomes that impossibility. That’s Tomino’s vision.

I feel like I understand Tomino and Anno, both. They made themselves understood through art and responded to the paralyzing realization that their words could be misapprehended, their motivations always ambiguous to the people in their orbit. A Newtype and instrumentality are two sides of the same coin or opposite sides of a fulcrum. The idea of instrumentality, where all human consciousness collapses into one singularity, takes the Newtype idea to the extreme. Where Tomino’s vision of the Newtype wasn’t without its complications — the Gundam stories showed Newtypes exploited and experimented on for military purposes — it was an optimistic vision that suggested a new axis of relation between humans. Char Aznable and Amuro Ray’s unending conflict was dialectical across Mobile Suit Gundam, Zeta Gundam, and Char’s Counterattack. But Tomino, across those works, made me believe that two people could understand each other. It was a sci-fi contrivance that made it possible, yet it felt real, and the unspoken communication between the two of them outside of the signifier is perhaps the greatest relationship ever depicted in a work of fiction.

Now, Char Aznable returns to the screen, larger than life, in GQuuuuuuX, a character rewritten to the letter of Mobile Suit Gundam. This is not a reinvention, but a reverent dialogue between the ideas of the two men. But Anno is also a bull in a china shop, and so too is named the minor Mobile Suit Character Anno spins up into a major one, Challia Bull.

Machu, GQuuuuuuX’s Newtype protagonist, fights like Amuro. She gets in the robot because she wants to, but she kills because she herself might die. And because she has a reflex or intuition that lets her know exactly what is at stake, signaled by a familiar sound, she survives.

Machu remarks in her self-introduction, “The heavens aren’t over our heads, but under our feet. Those of us born in the colonies know nothing of real gravity or real skies. Or, naturally, or real seas.” But space has brought about a reformation of humanity, the Newtype, that signals real connection as a replacement to an inferior alternative. This idea of something real seems to be one of the two biggest concerns in GQuuuuuuX. Machu is a Newtype, “the real thing,” because of her sense of “timing.” But what is real is relentlessly controlled by the corrupt Zeonic regime that relentlessly suppresses the spacenoids they supposedly intended to liberate. The residents of the Sides believe they will never be free under the rule of Zeon — the alternative would not have been any better, as the Earth Federation treated the denizens of space abhorrently in Zeta Gundam (1985). Shuji tells Machu late in the film, “you can be much freer.” That’s the second of those big concerns: freedom.

There’s always ambiguity about who is and isn’t a Newtype. They don’t look different from normal humans. They may or may not act differently. It comes back to battle prowess. Machu is a savant only because of her Newtype capabilities. Shuji dominates other mobile suit pilots because of his. Their understanding of each other is the real thing, because of what they can get across to one another without words. The realm of Newtype connection is represented with colorful sparkling visuals, Machu repeatedly calls it kira-kira, a Japanese onomatopoeia for something that shines. GKids left kira-kira untranslated in their subtitles for GQuuuuuuX.

Most considerations of freedom generally oppose it to the ideas of collectivity, sociality, and mutual obligation. Freedom exists to greater degrees the more one is an individual and is untethered to people or groups. This is the logic of American exceptionalism and American subjectivity. Be yourself, true to yourself, go your own way, etc. GQuuuuuuX presents a radically different vision of freedom, one that requires interconnection and mutuality. It’s a vision that is tinged with the residue of instrumentality. Machu can be “freer” to the extent that she accepts her sci-fi interconnection with others, Newtype or not. She can understand others deeply, though she doesn’t yet realize it.

For freedom to be the real thing in GQuuuuuuX, it requires a connection with another person that clears the bulwark of separation between subjects and yet allows the subject to remain themselves. Zeta Gundam shows the grisly fate of the Newtype connection misused, a subjective identity erased as Scirocco brain blasts Kamille in their final confrontation. But that’s the radical gambit of this show. To be much freer means to embrace, not reject, the other. And to embrace them in the most radical fashion of unmediated exposure. It’s impossible for the people that watch the show, prohibited from unmediated encounters with anything, let alone another subject. Even one’s own thoughts are mediated.

Not so in GQuuuuuuX. Machu and Shuji will stage an encounter in space that lays bare their consciousness, identity, and subjectivity all for the sake of real freedom.

Paradox Newsletter Radio

What is the superlative pop music? If you ask me, it sounds like this:

The song is “IYKYK” by XG. Seven letters for the sickest song that I guess came out last year? It samples the hit “Prism” by m-flo, all the way back from EXPO EXPO (2001). Their second record. That’s respect for the greats. It makes it even sweeter when Verbal shows up on this song:

But everything from AWE (2024) is incredible. I guess XG has a thing for acronyms. “Something Ain’t Right” is the album’s biggest hit:

And there are no notable samples to speak of, but some of that 90s US R&B and 2000s J-pop sound is evident. And the thematic similarity to “Say My Name” is right there.

Then, there’s “In the Rain,” in a McDonalds commercial airing in Japan right now:

This is the pinnacle of pop music and nothing will convince me otherwise. I reject the modern “poptimist” posture, just keep making music like this:

(From 4 Real [2003] and sampling the Neptunes drum hit from “Grindin’” that terrorized lunch room countertops for the next decade)

To share, regularly, this and other music I have been listening to, I made a playlist:

I plan to update it regularly and won’t always write about it when I do. So, keep an eye on it, and if you like stuff from it, save it or write it down. The range of stuff on here is a lot wider than my retro and retro-style J-pop. Good music lives here.

Weekly Reading List

This talk by Mark Rosewater provides some invaluable insight about the process behind making some of Magic: the Gathering’s most notable cards.

HC, presented without comment.

Until next time.