Issue #375: Taro Sakamoto vs. Matthew Murdock

I’m caught up on Australian Survivor (2002). I’m caught up on Sakamoto Days (2020). I saw Opus (2025), Drop (2025), A Working Man (2025), and The Amateur (2025) this weekend. I am a machine. But my next task is to get caught up on the third season of The Floor (2024). You might ask: “What is The Floor?” Prestige TV it is not. It’s a game show hosted by Rob Lowe. This current season features Brian O’Halloran in what might be his most profitable on-screen appearance. It combines the continuity of a reality TV competition with the routine gameplay of a typical game show. And it is full of people who behave very, very strangely. Highly recommended.

This week, something on the new Daredevil series and Sakamoto Days as well as a follow-up on The White Lotus (2021).

Sakamoto Days, Daredevil: Born Again, and the Prohibition Against Killing

Killing is the anathema to the notion of heroism in fiction. Consider Batman. In Batman Begins (2005), Nolan’s interpretation gives a more or less canonical moral underpinning for this choice. When the League of Shadows1 confronts him with the ultimate test of killing a thief, he refuses, saying, “It separates us from them.” Daredevil, similarly, embraces this thesis, particularly in his most recent on screen incarnation played by Charlie Cox. In the season three finale of Daredevil (2015), after beating the breaks off Kingpin (Vincent D’Onofrio), Daredevil taunts Kingpin for his capacity not to kill him:

God knows I want to [kill you], but you don’t get to destroy who I am. You will go back to prison, and you will live the rest of your miserable life in a cage knowing that you’ll never have Vanessa. That this city rejected you, it beat you. I beat you.

The shared logic of Batman and Daredevil is that the distinction between good and evil, while sometimes blurry, is painstakingly clear in one respect: thou shalt not kill. To kill someone, even for their wrongdoing, is evil. To imprison someone for that same wrongdoing is just.

Cynical readings of superheroism, though, have challenged this notion. Continuing the Batman metaphor, we can use his antagonism with the Joker for a thought experiment. If Batman captures Joker eight times, and Joker escapes imprisonment nine times, and with each escape kills one-hundred people, is Batman morally justified in continuing to repeat this process knowing that, likely, with the ninth capture and tenth escape, one-hundred more people will die? Does Batman’s absolute conviction to not kill have a greater moral significance than the foreseeable outcome that the Joker will escape from prison and rack up a greater count of murders?

This question is exactly the question of choosing between two separate moral frameworks: deontology and utilitarianism. You have likely read about these ideas in this newsletter before. In short, deontology evaluates an act’s moral value based on the act itself. Utilitarianism, by contrast, evaluates an act’s moral value based on its consequences. If an act saves one-hundred, one-thousand, or one-million people at the cost of one life, most utilitarian frameworks would find the act to be just. For deontology, regardless of the outcome (one-million lives are saved, one person dies), it would depend what the act is. Are we talking ledge-hanging, trolley, gunshot, or poison? Were the lives saved and lost based on inaction, or did they require an agent to take action? Depending on the specifics of the deontological framework and the principles it embraces, the act itself would be the sum-total of what counts when it comes to evaluating the moral value.

Moral frameworks are meaningless outside of a greater context. For me, the best context for exploring them is a society. The rewards and risks of a society that embraces utilitarianism are, in my view, fairly intuitive. The thing a group might want to encourage people to do is the thing with the best outcome, that which maximizes ‘general happiness,’ “a good to the aggregate of all persons” (Mill Utilitarianism 812). However, the Trolley problem is one of the routine objections to utilitarianism. Even if we embrace the one vs. one-million exchange of lives, how do we account for the trauma the person that has to kill the one might experience? What harm might they visit on others as a result? What if the one that has to be killed to save the many is Einstein? What if this now-deceased one had the capacity to save one-trillion people through some kind of medical breakthrough? Is it not lives, but years of life that suddenly become the measure for ‘general happiness’?

All of this is subordinate to utilitarianism’s greatest problem: we cannot know with certainty that our actions will occasion the result we expect. This is less a problem for utilitarianism as a moral system and more a problem for its societal application. Utilitarianism, generally, doesn’t consider what one expects will happen as a result and evaluates above all else what actually happens. Nonetheless, given that people can act with the intention to “maximize happiness,” but, in fact, end up doing the opposite by utilitarianism’s own measures, is a serious problem.

By contrast, deontology is appealing because it eliminates some of the repulsive calculus one must engage in to determine an act’s moral value (is it moral to kill 50 elder people to guarantee the long life of a newborn?). It also evades weighing one’s intention, with a focus on the action itself. It is wrong to kill. It is wrong to lie. Immanuel Kant’s categorical imperative endeavors to suture such moral evaluation with rationality, “act only in accordance with that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it become a universal law” (Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals 313). In other words, one should only act according to principles that are universalizable. There are shades of the golden rule here. The societal application here is very clear. It seems more reasonable to expect people to act according to simple, concrete moral principles as opposed to acting based on complex evaluations of an action’s outcomes.

Batman and Daredevil, then, are Kantians. Not only do they act in accordance with their moral convictions, they expect them to be universalized. Though they often stop crime that doesn’t involve murder, they will also confront other supposed heroes — “anti-heroes” — who are willing to kill in their pursuit of justice. The stage is set for a grand confrontation between deontology and utilitarianism in the constant opposition between Daredevil and the Punisher.

The Devil on One’s Shoulder

In Daredevil: Born Again (2025), Cox reprises his role as Daredevil alongside D’Onofrio as the Kingpin and Jon Bernthal as the Punisher. Daredevil meets the Punisher in episode four of the new series, “Sic Semper Systema.” Their confrontation is staged on the heels of Foggy Nelson’s (Elden Henson) murder by Bullseye (Wilson Bethel). Daredevil throws Bullseye off the top of a building, seemingly with the intent to kill him. Bullseye survives, but Daredevil retires. Now, finding the Punisher to try to demystify the death of another vigilante, the Punisher delivers a monologue condemning Daredevil for the rigidity of his morals and the failure to appropriately respond to Foggy’s death:

I don't think you came here for my help. See. I think you want my permission. You wanna get your hands on somebody, huh? Wanna hurt 'em. Maybe you're a little bit scared. A little scared about what that means. … Yeah, that guilt, that shame, that's my home, Red. And I can see it on you, I can smell it on you. It's all over you. … You come at me with that horseshit about saving lives. How 'bout that friend of yours? You save his life? You lost him, didn't you, Red? … It's not about him? You hate yourself. It's eating you up because you ain't done a goddamn thing about it … and it's gonna keep eating at you. It's gonna keep eating, and eating, and eating. … So what now? Every day Bullseye goes to the chow hole, eats his slop, you know he gets to breathe the same air that you breathe. You feel good about that?

Daredevil replies to the Punisher, “he got life,” with the Punisher getting in the last word, “How ‘bout old Foggy? He get life?”

This exchange cuts across both the dispute as to whether deontology or utilitarianism are more desirable moral frameworks and the question of whether killing or not killing determines someone’s position as a hero. From the Punisher’s perspective, Daredevil operates against his “violent nature,” thus rendering his heroic mask deceptive. Daredevil also seems to be violating a rule built into the U.S. legal structures that governs appropriate use of force. From the Punisher’s perspective, a lifetime of imprisonment for Bullseye is not proportional to the lifetimes Bullseye has taken. Accordingly, Daredevil has failed to live up to an obligation.

If deontology prevents the crossing of certain boundaries, following the Punisher’s rather extreme embrace of proportionality (an eye for an eye), then perhaps it is a moral framework ill-equipped to function as the foundation for any punitive logic. This is true of utilitarianism, too — moral frameworks are about evaluating action, not administering punishment. But the punishment that the Punisher doles out is governed both by the logic of proportional reprisal and the utilitarian logic of moral evaluation. Instead of expecting people to anticipate outcomes correctly, he kills those who have killed, and expects that by doing so he is preventing future deaths. Bullseye, after all, like any comic book rogue, will inevitably escape from prison to wreck more havoc.

“Everyone is precious to someone”

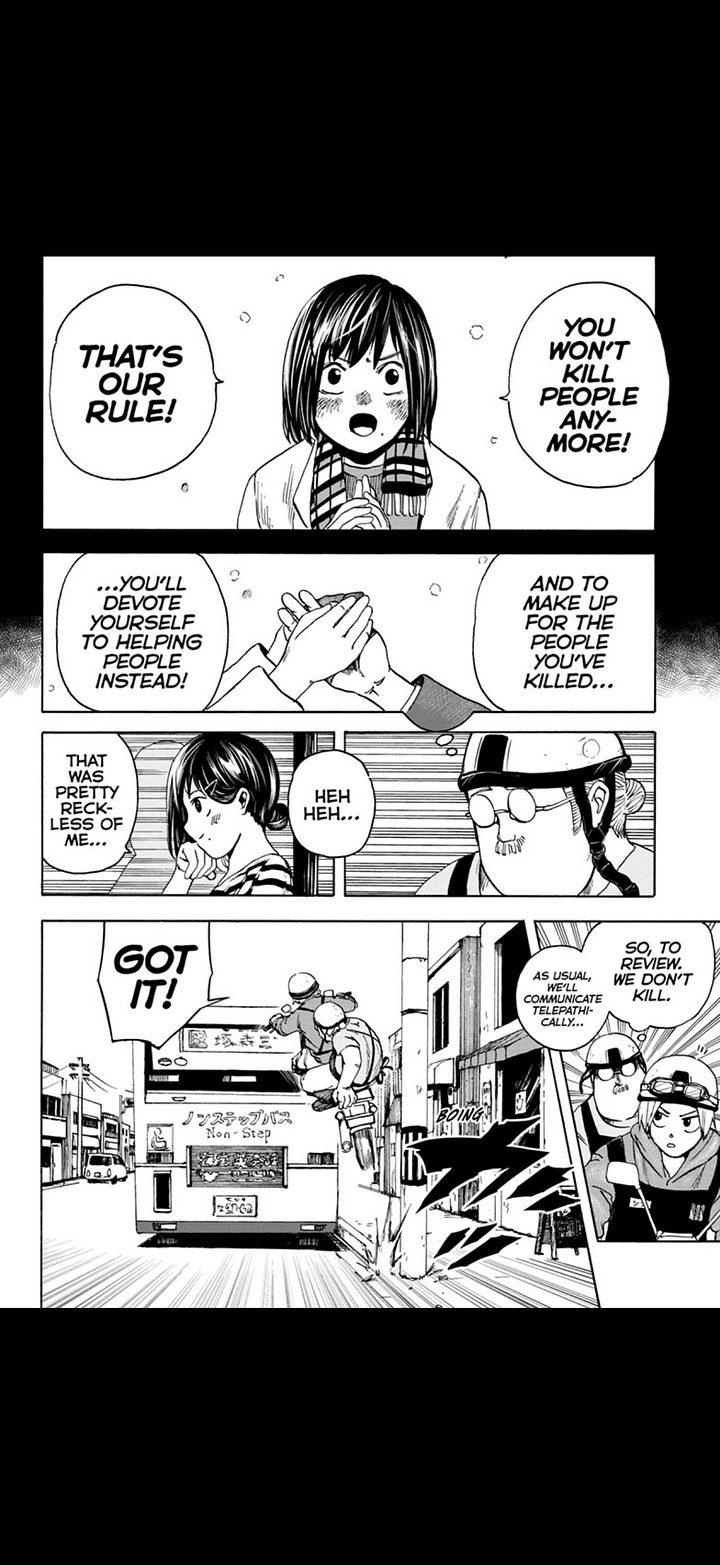

Japanese comic books have fewer high profile deontological exemplars with hardline rules against killing. One that has emerged recently, however, is Sakamoto from the manga Sakamoto Days (2020). The series follows Taro Sakamoto, a retired assassin, who has committed to not killing at the behest of his wife. Sakamoto has the very manga-like gift of turning antagonists into allies, and accordingly turns a number of assassins targeting him into relative pacifists through his adventures.

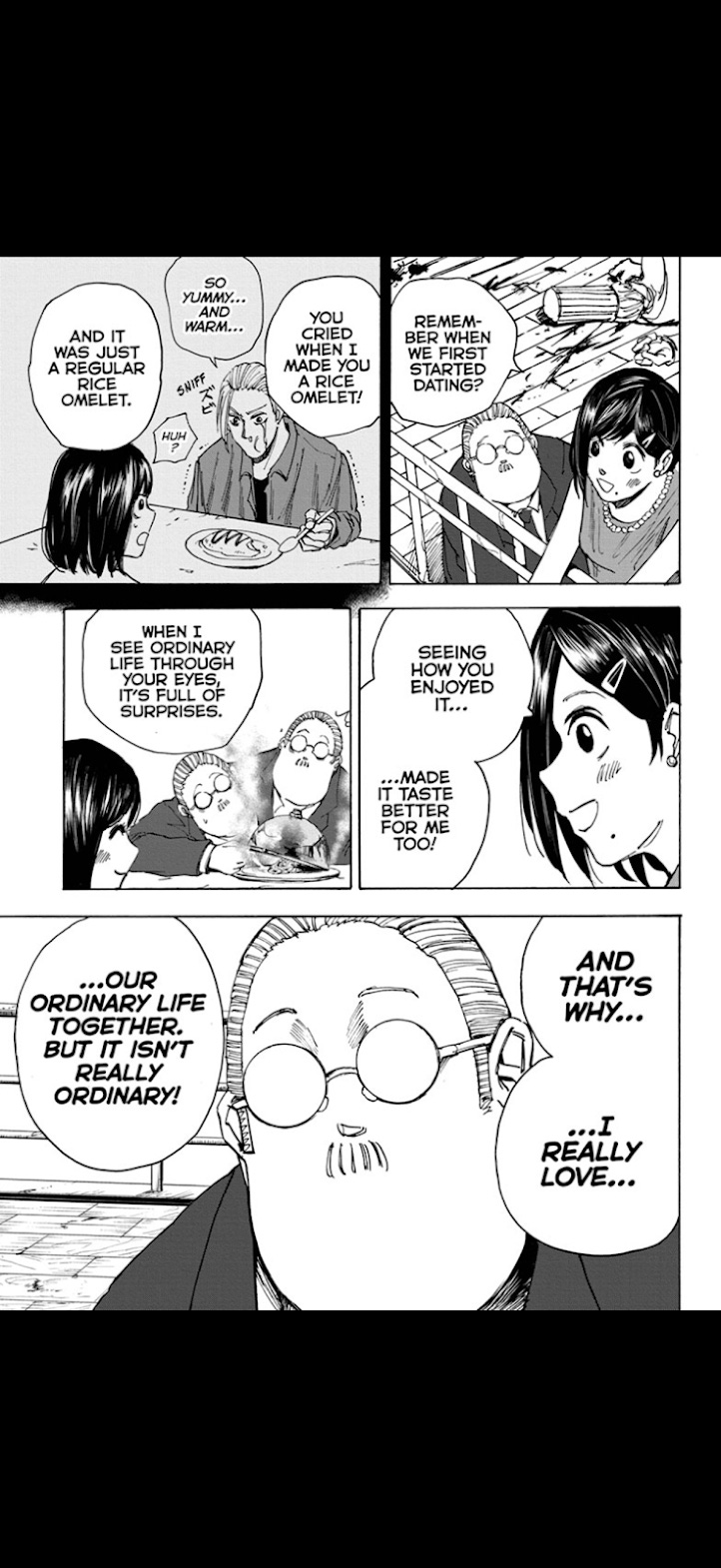

Sakamoto’s wife, Aoi, demands not just that Sakamoto stop killing but that he also “devote[s] [himself] to helping people instead,” as contrition for his assassinations. The logic of Sakamoto Days is a bit more optimistic than that of the various stories of Batman or Daredevil. Instead of a villain inevitably escaping to take more lives, and the hero challenged because of the confrontation between the deontological and utilitarian calculous, the two are frequently in alignment for Sakamoto. The defeat of an enemy and the exceptionality of Sakamoto’s “ordinary life … [that] isn’t really ordinary” often results in the enemy joining in his commitment not to kill.

However, Sakamoto must subjugate his opponent by his physical power before they will share in his moral commitment. This is most often what is at stake for Sakamoto, that his not killing has made him weaker than an opponent who is willing to kill — though this is rarely the case.

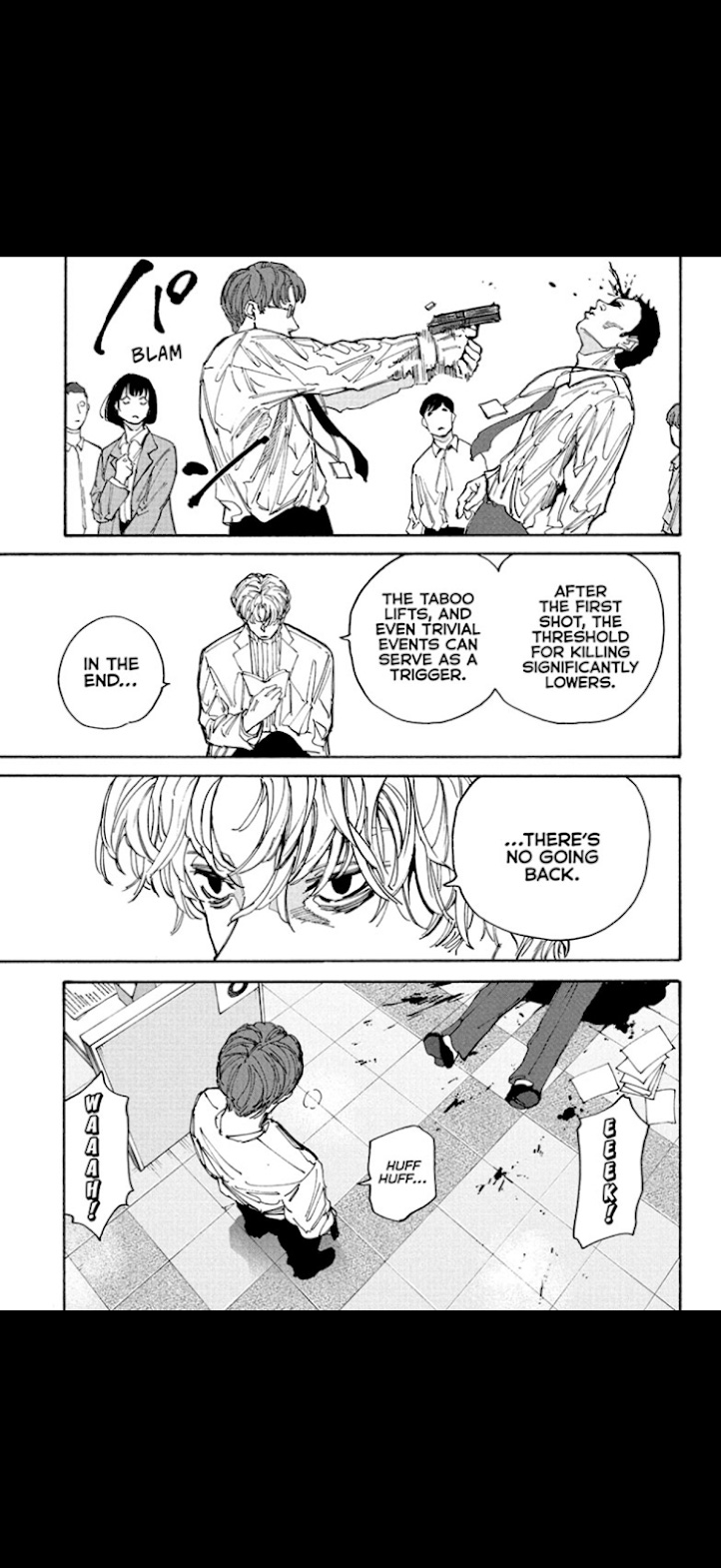

In a recent chapter, however, a supporting character, Shin, decides to abandon his adherence to the Sakamoto Family Rules and kill someone.

Sakamoto’s reason for not killing tries to square the circle of utilitarianism and deontology by creating a world where people generally don’t want to kill each other if they can avoid it and suggesting that part of the harm of killing another is the loss of the potential good they could do and the harm to their loved ones that occurs as a result of their death. It’s not the case that killing is wrong for its own sake, but it generally produces outcomes that maximize harm and minimize happiness. Shin’s confrontation with a sociopathic villain, Tenkyu, challenges those assumptions and creates a scenario where refraining for killing someone doesn’t present the benefits the Sakamoto Family Rules are found on.

As a result, Sakamoto Days must pivot to its final bulwark of its all-encompassing objection to killing: egoism, a moral framework that suggests people should act for their own benefit. The cost that is too much for Shin to bear is the cost of killing to himself, killing is most harmful to the killer who must endure the guilt of their act. This is also the basis for Sakamoto’s quest to stop another supporting character, Akira, from killing one of the manga’s villains.

Sakamoto Days offers a very robust consideration of killing in the context of superheroism and normal social function. Recent turns in the manga have gone on to subvert the premise that people, fundamentally, don’t want to kill by setting up a purge-like scenario in which killing is authorized by the government.

How Sakamoto Days differs from Batman or Daredevil, then, is its consideration of the wider social implications of killing. In the various incarnation of the two American superheroes, it’s taken for granted that people generally are not interested in killing another person. Sakamoto Days opens the possibility that there’s nothing unique about the “violent nature,” the Punisher attributes to Daredevil. The moral conflict of Sakamoto Days is far grander in scale than the narrow consideration of whether one particular man should or shouldn’t kill in the interest of service.

Parable vs. Thought Experiment

Sakamoto Days is vastly different in its treatment of heroism and the prohibition against killing than Batman or Daredevil stories. It contends with the violent impulses of the culture as a whole, taking them as a normal part of social life, as opposed to the U.S. superhero examples that treat these questions in exclusively exaggerated contexts for the purposes of staging a legible thought experiment. Yuto Suzuki’s manga is less of a thought experiment and more of a didactic moral parable. In its attempt to teach a life lesson, it diverges from the precise moral frameworks U.S. comic adaptations often utilize. I have equal admiration for both approaches. In the particular cases of the Sakamoto Days manga and the Daredevil: Born Again series, the creative forces behind these works have done an admirable job translating these complex ethical questions to the page and screen.

High & Lotus

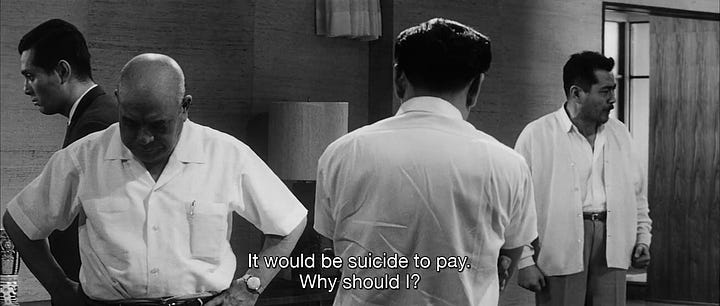

With all love and respect to Spike Lee, my film GOAT, I think Mike White would have been a great choice to adapt High and Low (1963). I could imagine a shoe magnate blackmailed by kidnappers who accidentally grab his chauffeur’s son as a White Lotus (2021) plot. But maybe Kingo (Toshiro Mifune) and Reiko Gondo (Kyōko Kagawa) are too benevolent and heroic for Mike White characters.

Early in the film, Reiko begs Kingo to pay the ransom for the child despite their own son safe at home. As a strong contrast to Tim (Jason Isaacs) and Victoria Ratliff (Parker Posey), Reiko insists that despite her privileged upbringing she could survive poverty.

Kingo has no reason to Amityville Horror his family, but instead disappoints them at first by his refusal to pay the ransom.

The distinction here is obvious. Tim must hide his financial destitution from his family, while Kingo’s family implores him to accept destitution in exchange for the kidnapped child’s life. Tim losing his wealth because of his wrongdoing is a failure that compromises his identity. Kingo’s identity is propped up by his capacity for compassion, as he does ultimately pay the ransom on the behalf of his driver’s child.

Both scenarios are complex moral quandaries as opposed to straightforward moral parables. Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto writes in Kurosawa (2000):

Gondo is not presented as a morally despicable person or somebody who is interested in taking advantage of his position to line his own pocket. He does try to stage a little coup, but his takeover attempt is devised not to merely make more profit but to produce better shoes. As we can see in his words of encouragement to Jun and Shin’ichi (“Try your best, both of you!”) and in the testimony of a worker at the factory, Gondo is a fair and even-handed man. The choice he is forced to make is therefore not simply between pure personal greed and humanitarian sentiment. The situation in which he inadvertently finds himself is, as he says, just an absurd one. Gondo’s agony is represented by Kurosawa and Mifune in such a subtle way that we cannot but probe into his moral dilemma. Yet the fundamental absurdity of the situation does not allow us to find out what in the end makes Gondo decide to ruin himself financially. This absence of a clear motivation is further foregrounded by Reiko’s remark “Shikata ga nai” [it can’t be helped]; that is, Reiko and the boy’s father can’t help asking Gondo to save the kid, and Gondo can’t help paying the ransom even if as a result the Gondos lose everything they own. Reiko’s remark is not refuted by any character including Gondo. This is particularly surprising because the idea of shikata ga nai is exactly what the Kurosawa hero rejects time and time again.

Yoshimoto goes on:

When Gondo makes up his mind to pay the ransom, he jumps into the darkness without knowing whether he will land safely at the far side of an abyss. Significantly, what emerges through Gondo’s blind leap is a certain sense of collectivity … Because Gondo does not save his own son Jun but saves his chauffeur’s son Shin’ichi, his most important action takes place outside the familial space of blood relation. It must also be distinguished from a mere interest group such as the group of capitalist investors who demand full repayment of a loan from the financially ruined Gondo.

Following Yoshimoto’s reading, Kingo’s heroism is a result of the responsibility he chooses to shoulder. If it can’t be helped that Reiko must entreat her husband in this way and, similarly, Kingo’s obligation to pay the ransom also can’t be helped, we find Kingo in the exact opposition position to Tim Ratliff (as I discussed last week).

Kingo is pulled into his act of heroism by the social obligations that emerge as a result of his presence in a collective society. He is commensurately rewarded with fame and admiration, although High and Low also shows that fulfilling one’s social obligations often requires to act in opposition to one’s financial interests. Just because the act of compassion is compelled by these social ties doesn’t detract from its authenticity in the view of the film.

Tim is, instead, chafing against the responsibilities that are a product of expectations. This causes him to act out and shrink from the possibility of murder that could cause his family not to experience the subsequent crisis his financial wrongdoing will visit upon them. In my view, the most important distinction between Kingo and Tim is their fixity in certain formal positions in the logic of a narrative. Kingo is a hero, something Kurosawa accepts as a feature of his universe. Mike White doesn’t depict those kinds of characters. He explores flawed, amoral, or immoral actors who navigate the world in a state of imperilment or confronting self-annihilation. Even as Kingo loses everything, his sense of self is stronger than ever.

That brings us back to the initial parallel between Reiko and Victoria. But their relation to their identity mirrors that of their husbands. Reiko accepts the possibility of poverty to be someone who is compassionate and lives in accordance with the collective obligations society imposes. Victoria is unable to confront the possibility of change because her sense of obligation is confined to those to whom she is bound by blood. Victoria can’t be the heroine that extricates Tim from his sense of doom, she can only exacerbate that sense. Reiko offers a point of transition for Kingo, “starting over,” where Kingo’s good business sense and moral uprightness could lead to a satisfactory, if less luxurious, life.

In understanding the distinction between these characters, I think I’ve talked myself out of a Mike White helmed High and Low remake. Spike Lee, like Kurosawa, knows how to treat the flawed but ultimately heroic character who answers to something higher than his immediate needs. If Yoshimoto is right, though, Kingo is a hero that is heroic precisely because of his acceptance of fate — his unflinching gaze toward and acceptance of the oncoming tsunami, if we want to carry through The White Lotus metaphor. This makes him an unconventional hero if there ever was one.

Weekly Reading List

https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/O/bo243090734.html — I’ve been enjoying Mendelsohn’s new translation of The Odyssey. His introduction and notes are particularly strong.

Obviously there’s not usually much going on in these talk show appearances, but I’m intrigued by Spider League.

A very informative summary of mid-2000s Bay Area rap music.

I am sure this video is specifically engineered to be one of those “satisfying” type of things, but it achieves its intended purpose.

Calling them the League of Assassins, as they are in the comics, might have clued Bruce (Christian Bale) into the fact that they would reject his moral philosophy.

Roger Crisp (ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998

Mary Gregor (ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998