Issue #402: Optimistic Martial Arts Manga

Through this round of Music League, I’ve come to find out live albums are polarizing.

Many of the Music League competitors have come out as live album haters. But I love them. This week’s playlist is a pretty good showcase as to their unique quality. There are four hc songs on the playlist, all somehow randomly (or programmatically by whatever algorithm governs playlist order for Music League) organized at the end of the playlist. We’ve got “Big Takeover” from Bad Brains at CBGBs in ‘82, “Laughing Boy” from Poison Idea at Portland Meadows in ‘92, “Furder” by Ripcord at Parkhof Alkmaar Holland in ‘88, and “Firestorm” by Earth Crisis at The Whiskey in ‘96.

I don’t want to talk about the standings since there are people who haven’t voted yet, but these songs are being appropriately appreciated. Hardcore is a live music genre and these recordings capture something the studio versions don’t. The “Firestorm” recording is the platonic ideal of live hardcore — actually, all live music, in my view — with the songs lyrics more ledgible shouted by the crowd than from Karl Crisis himself. “Furder” is my favorite song on the playlist overall, though. I should probably say a lot more about Ripcord either here or in a zine, but in the mid-80s they were setting a new standard for how you could use fast(er) tempos in hardcore music.

There’s a lot of other genres represented on the playlist, too. It starts with “Symphony No.6 in B minor, Op.74 - ‘Pathétique’” from the Leningrad Philharmonic’s interpretation of Tchaikovsky. Though classical is also a live music genre, the exigencies of recording have resulted in “live” sessions sometimes inter-cut with recordings of actual performances, it’s not clear to me that this recording was a performance in front of an audience. Someone also submitted Daft Punk “Alive 1997,” which definitely fits the bill of the prompt, but it’s an entire album in one track. Whatever, it’s pretty good. Johnny Cash’s At Folsom Prison (1968), Etta James’ Rocks The House (1963), and Sam Cooke’s One Night Stand (1963) are obviously classics of live recording. None have lost their luster, although I think the Cooke album is especially good.

I got put on to Live Skull through the Curtis Mayfield cover submitted for this round. And I have listened to Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus (1960), very often, especially given the song from which Hortense Spillers takes an essay title. It is also not a live album, though Mingus tries to convey the sense of a live performance during the studio session.

As far as music being to my taste, I think this has been the best playlist so far. Next week is a category I came up with called “Where I’m From” with the description: “A song from your hometown or long term residence. Where you’re from, where you’re at, etc, etc.” The spirit of the prompt is to submit something from where you grew up, but I wanted to give an out for those who really couldn’t come up with anything.

Music League has been pretty successful so far, so we are gearing up for another season once this round concludes. I’ll start it up in early November and if you missed out on this round, you’ll have another chance to join. We’ll probably have some attrition between the current season and the next one, so don’t be afraid.

Kengan Omega: A Martial Arts Manga Where Everything Turns Out Alright

Among fans of anime and comic books, there is an age old question: “who would win in a fight, Goku or Superman?” I would not be surprised to learn more ink (as pixels, of course) has been spilled on this question than Hegel’s Geist or Freud’s unconscious. Answers are as varied as one might expect. Some inquiries respond with other questions: “which version of Superman?”, “which version of Goku?”, “are they fighting for fun or is there something at stake?”, or “do they have prep time?” Some would prefer to use the logic of the narratives that house these fictional characters to avoid the question, “they would never fight each other!” I have always thought the best answer to be one that uses the logic of narrative storytelling as such, “the winner will be decided by what best serves the story.”

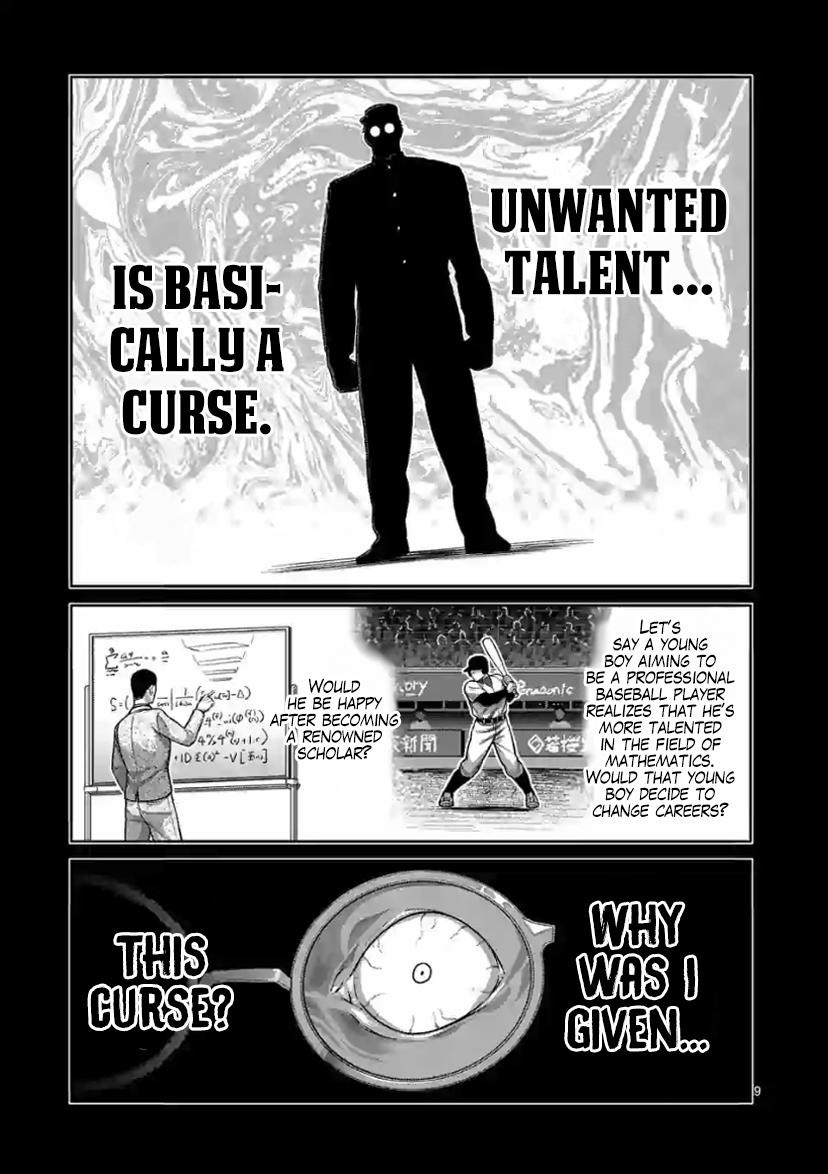

Goku and Superman don’t exist, so it is impossible to stage a conflict between them outside of the imagination of some author. Their relative level of combat ability is not even consistent within their home texts. Neither do these texts offer some measure through which the characters can be definitively compared. And then, assuming these two characters are being inserted into some realistic realm with rules of physics and logic that would govern their loss or victory independent from some story the fight is in service of, there is the unpredictability of combat itself. Yabako Sandrovich writes in his manga Kengan Omega (2019):

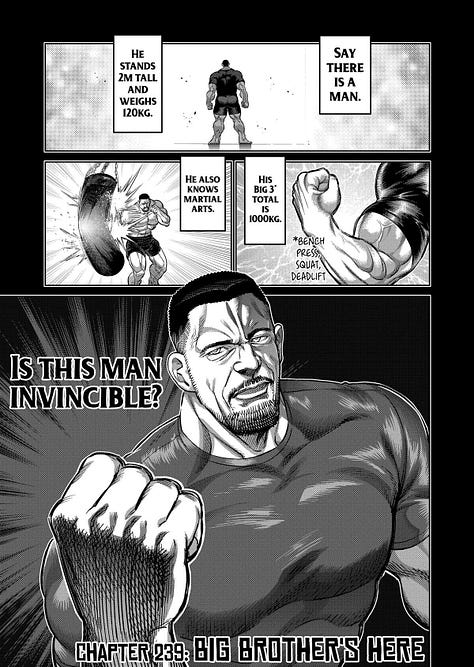

Say there is a man. He stands 2 meters tall and weights 120 kilograms. His [bench press, squat, and deadlift] total is 1000 kilograms. He also knows martial arts. Is this man invincible?

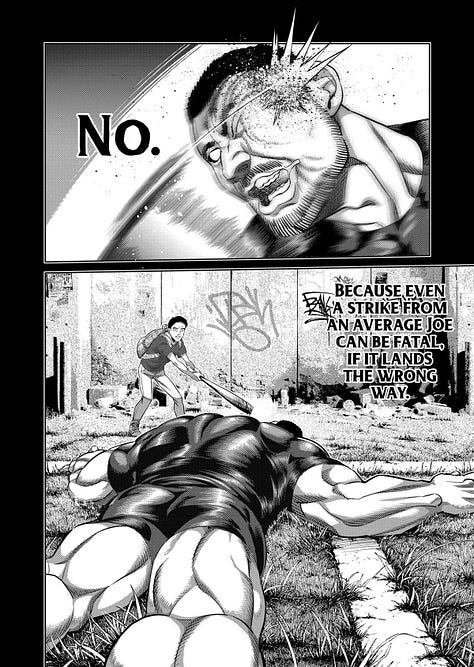

No. Because even a strike from an average joe can be fatal, if it lands the wrong way.

A cerebral hemorrhage can kill anyone, regardless of supreme combat skill or godlike power reserved for the realm of fiction. Accidental deaths in boxing and other combat sports happen, generally, despite the participants following rules that exist to prevent their killing one another.

Despite the fact that fights in fiction are resolved to the end of serving a broader narrative and that fights in real life are not perfect adjudications of two peoples’ relative strength, people will continue to spend a lot of time trying to figure out whether Goku could beat up Superman, or whether Spiderman could beat up Batman, or whether Luffy could beat up Kenshiro. There are even works of fiction that attempt to eliminate the incentives of storytelling and resolve a fight according to some internal “powerscaling” logic, like Tenkaichi: Nihon Saikyō Bugeisha Katteisen (2021).

As I wrote last year, author Yōsuke Nakamura eschews narrative logic and the accompanying tropes, valuing a fight which has an unpredictable outcome above all else:

Since we all love battle manga, the winners are decided by a consensus between Nakamaru Sensei, Azuma Sensei, and me, Yamanaka.

“Let’s have this one win to betray the reader’s expectations” and “this one is the secret protagonist so they’ll win.” There is no such speculation.

It is just as simple as the one who gets the most overall votes between us, the 3 battle manga fans, wins.

I guess we could say the same earnest fight as in the martial arts tournament is happening within the framework of the manga…

Tenkaichi doesn’t have a designated protagonist. In Tenkaichi, everyone is a central character. Enemies, allies, there are no sides.

That’s why… [sic] the manga is completely free of narrative tropes such as the “justice prevails” and “the promise of the story”. [sic]

A battle tournament in which not even the creators can predict the outcome.

Sandrovich’s Kengan Omega, another martial arts manga primarily made up of one-on-one battles, is different from Tenkaichi. Instead of trying to stage “authentic” fights with uncertain outcomes, the winner in Kengan Omega is always the one Sandrovich needs to win for the purposes of where he will take the story.

Sandrovich’s approach, and his ongoing manga, has its detractors. Kengan Omega is a sequel to 2012’s beloved Kengan Ashura, a manga that takes place more or less entirely during a single martial arts tournament. While Keisuke Itagaki’s Baki series or George Morikawa’s Hajime no Ippo (1989) may have perfected the formula for manga in which the overwhelming majority of their action takes place during martial arts competitions, it is not an easy formal conceit to maintain. Sandrovich, instead, has expanded the view of his series. Ashura has a conventional narrative structure with a focus on the protagonist, Ohma Tokita, and the narrative accordingly revolves around him. Omega substitutes Tokita for a much less compelling protagonist, Koga Narushima, but Narushima is hardly Omega’s focus. Instead, Omega is a true ensemble piece, spotlighting a wide variety of Sandrovich’s characters.

The faults of Omega may come across as strengths to some readers. While Ashura seemed to be an unforgiving, brutal manga where characters could suffer grisly, permanent injuries or die, Omega has undone most of the ostensibly final ends for Ashura characters. Sandrovich has, perhaps, become too attached to his characters. Omega never seriously imperils them, and the profound violence and brutality of the manga’s fights end with a handshake, a pat on the back, and mutual respect between the combatants. One might also critique Sandrovich for taking an approach similar to Tite Kubo when it comes character design, development, and presentation within a story. Kengan Omega has a lot of characters, with each new tournament adding more to the broad sweeping narrative that has come to involve international criminal conspiracies and the threat of global destruction.

I’m still on the Kengan Omega train, though, despite its growing saccharine quality and characters’ strange fixation on Narushima. The treatment of Omega’s protagonist resembles that of a fan fiction author-insert character, the constant object of fascination, reverence, pity, and general attention that totally defies the text’s narrative logic. Sandrovich softens this annoyance by absenting Narushima from large portions of Omega’s plot.

Narushima aside, Sandrovich has a great sense of which characters deserve more attention and which don’t. Even the characters who don’t get much time on the page are reasonably well-developed during their brief moments in the spotlight.

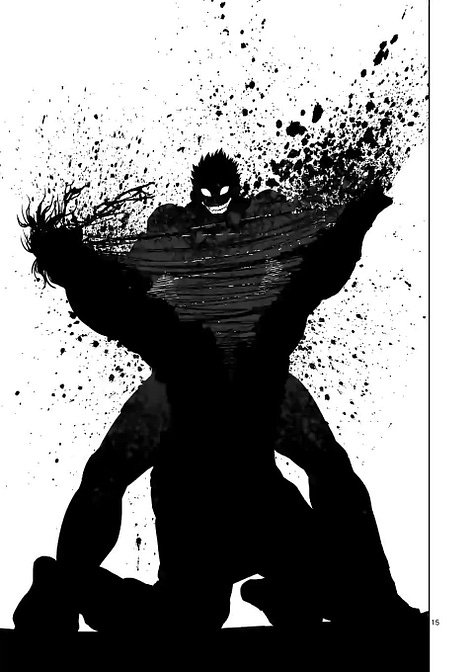

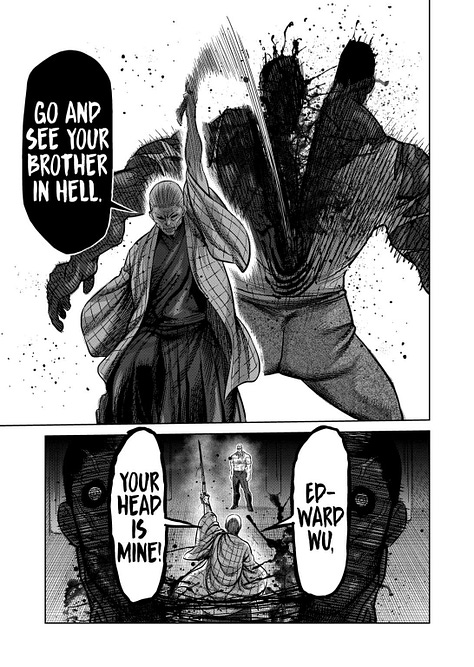

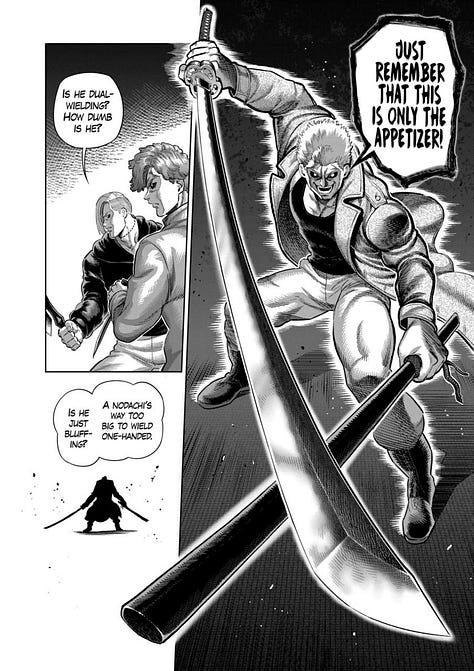

Daromeon, Kengan Omega’s illustrator and Sandrovich’s creative partner, contributes tremendously to the manga’s staying power. His illustrations are always dynamic and full of life.

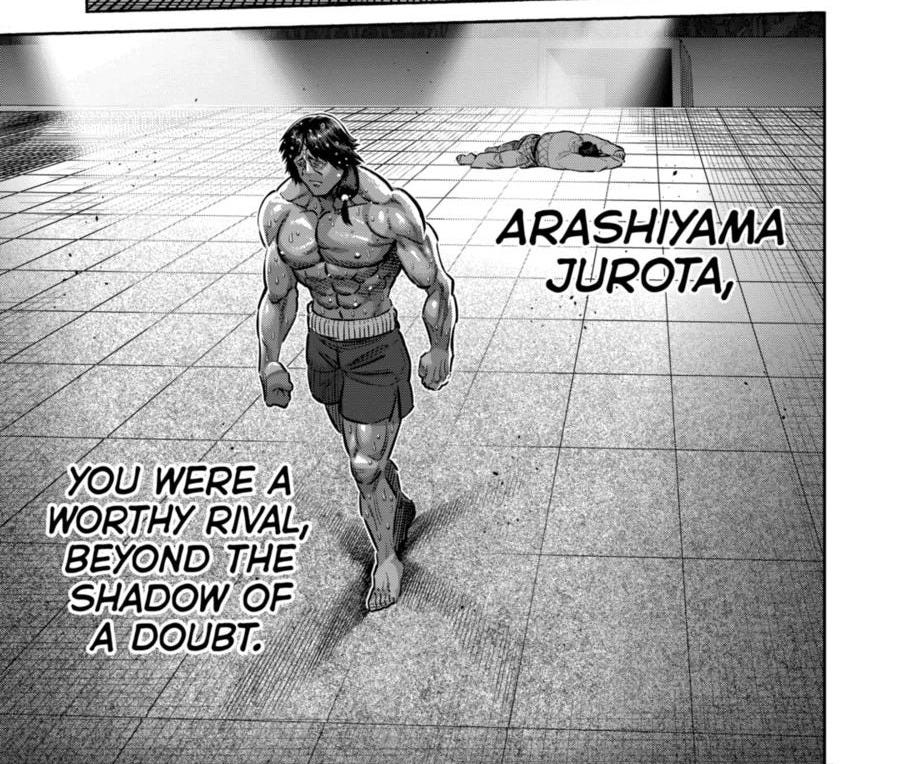

I am particularly struck by this page from a fight between Agito Kanoh and Jurota Arashiyama:

In more recent Omega chapters, Daromeon has drawn the movement of human arms with the unnatural curvature here to capture movement. I especially like his willingness to exceed the bounds of the frame, with Arashiyama’s arm covering over the gutter above.

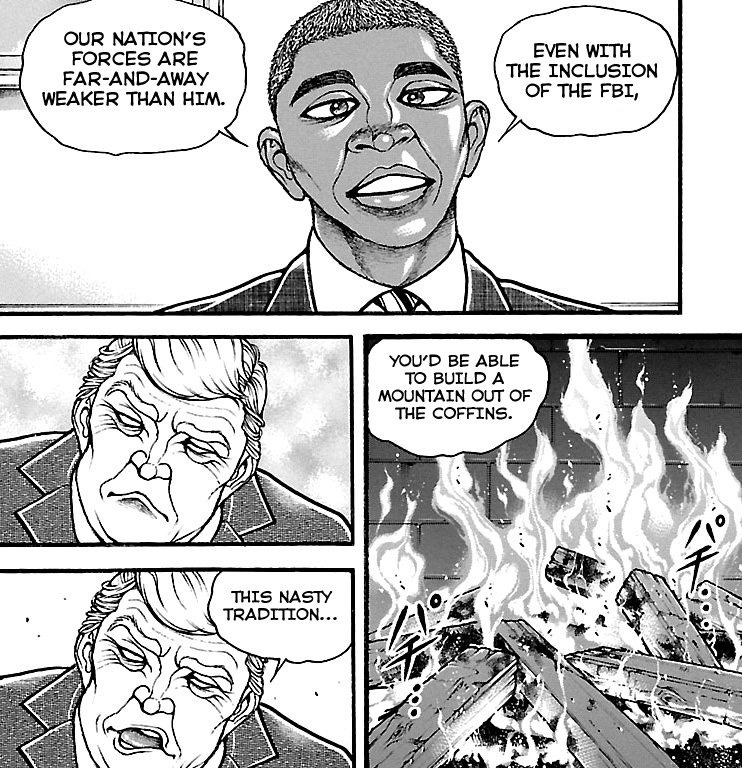

Ashura and Omega have sustained a lot of comparisons to Itagaki’s Baki, for good reason. Sandrovich borrows liberally from Baki’s character designs and narrative tropes. But Omega has become perhaps the most pointed antithesis to Baki as one could have in the same genre and medium. Itagaki is relentless in his study of Baki Hanma, maintaining his focus across thirty-three years and counting. The shadow and perennial antagonist for Baki is his father, Yujiro, who Itagaki presents as incomprehensibly powerful, even able to destroy the entire U.S. military.

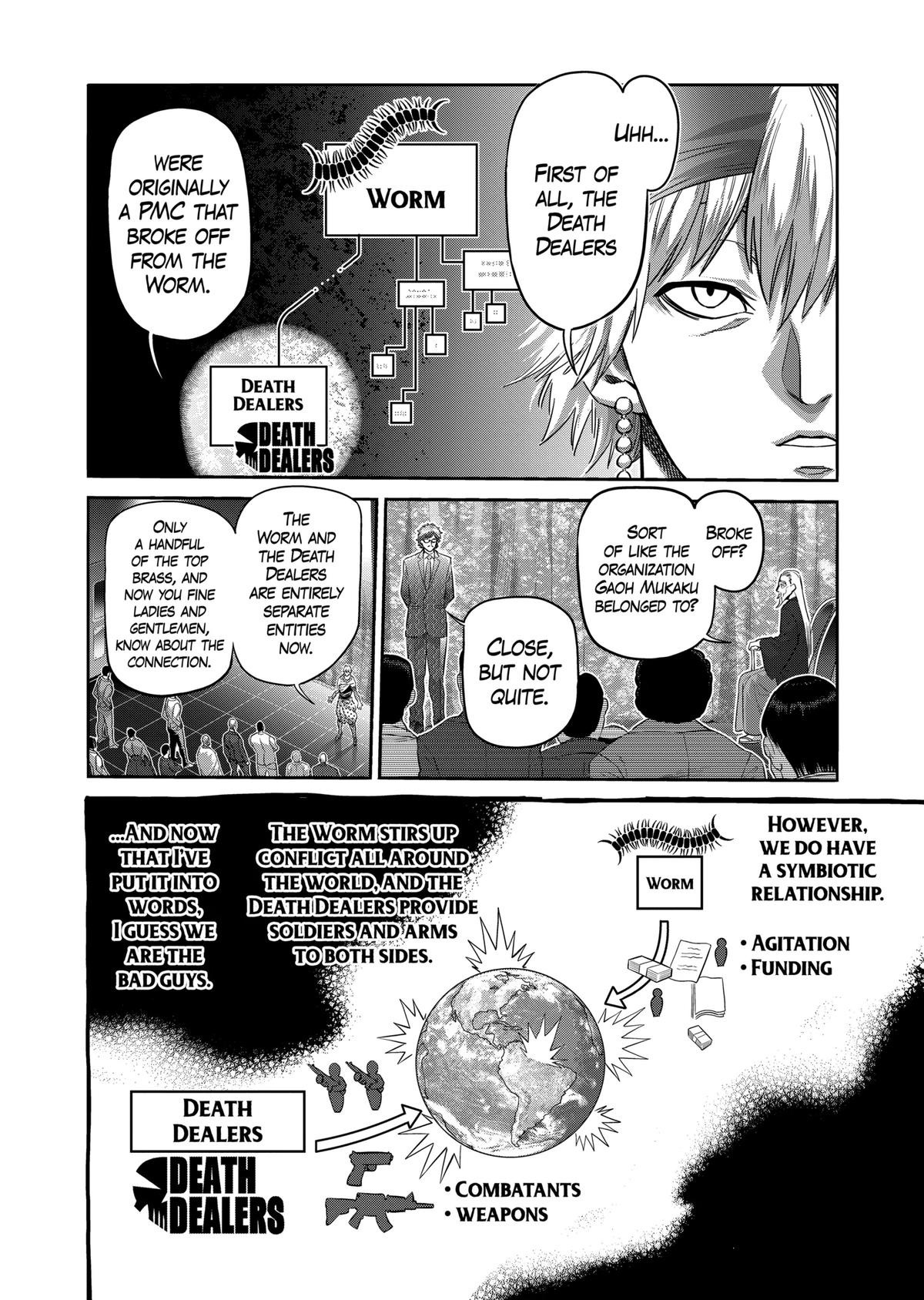

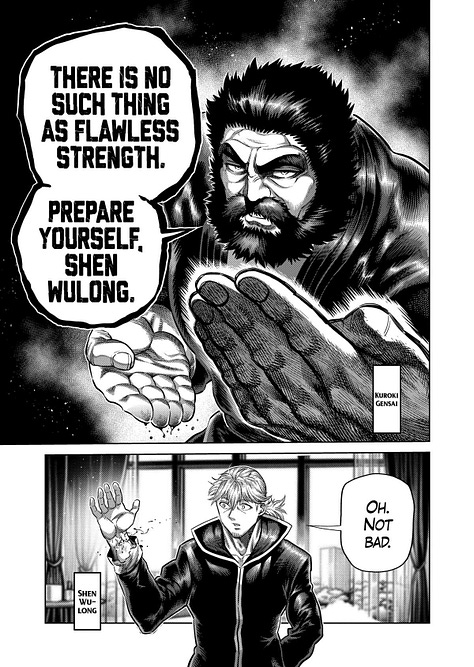

Despite Yujiro’s relentless power and malevolence, the Baki series rarely involves international intrigue. Omega, by contrast, has made a complex conspiratorial plot the lynchpin of its narrative and the engine that motivates every action. At the core of this plot is a character analogous to Yujiro Hanma, Shen Wulong.

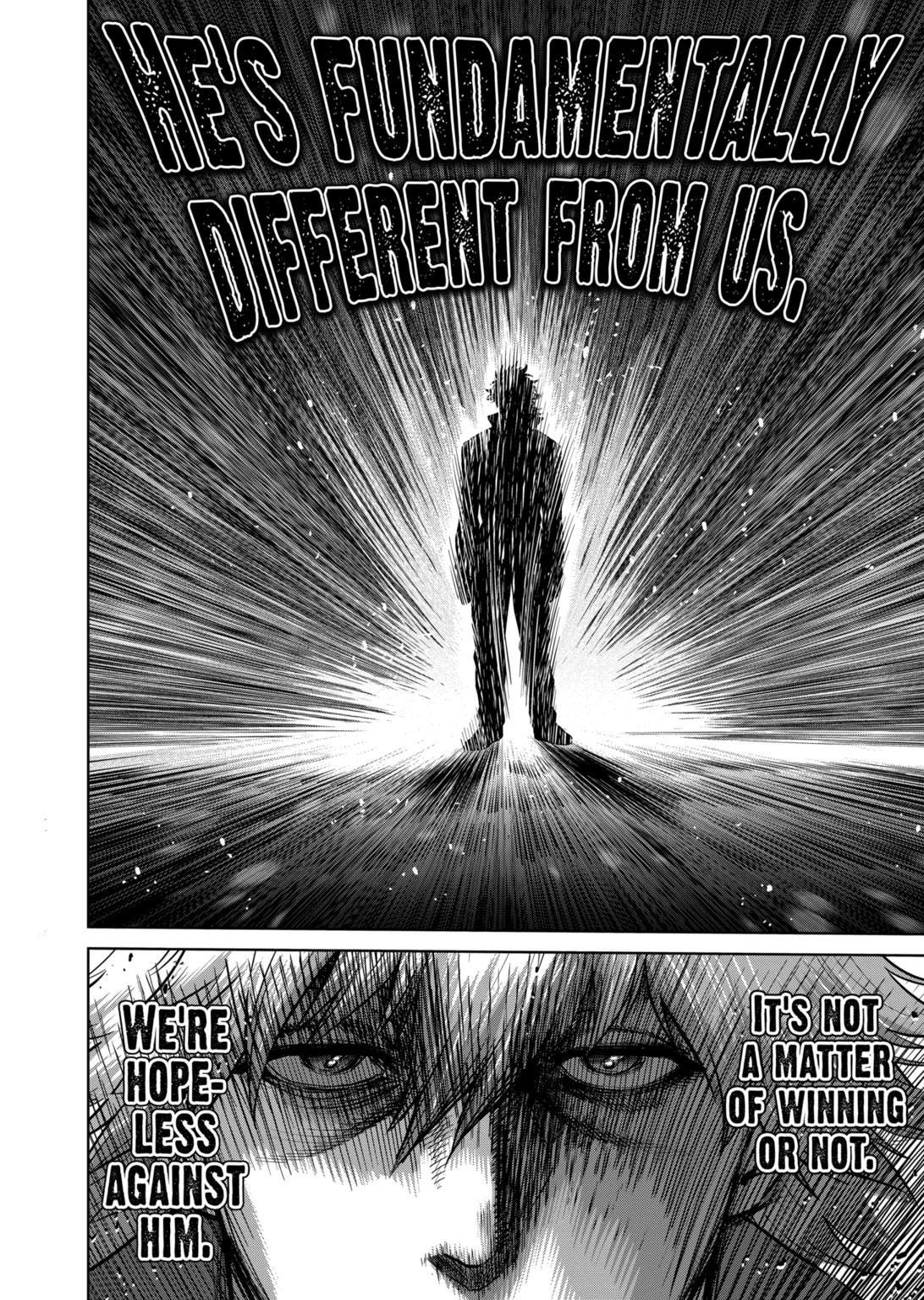

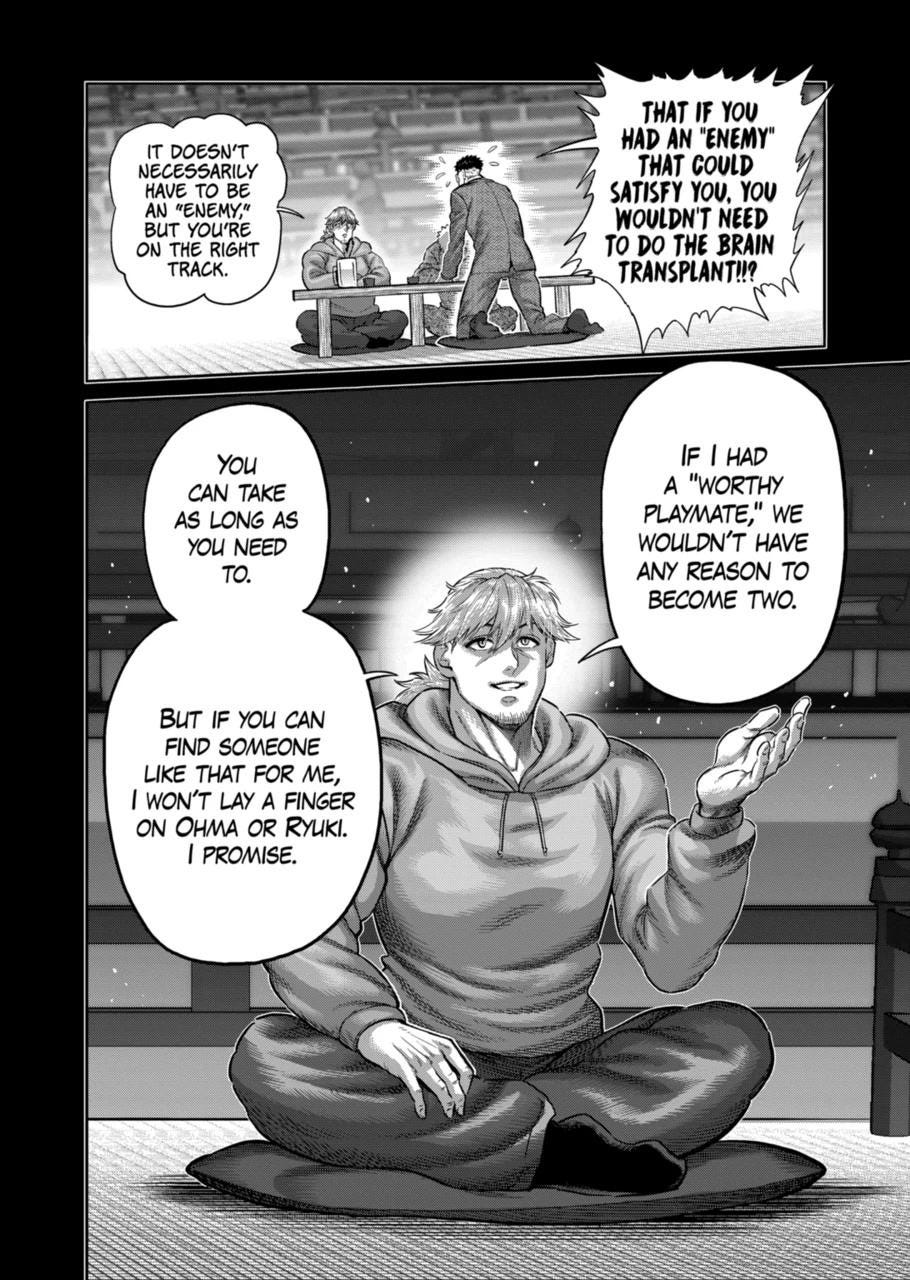

Though Wulong and Yujiro both serve the purpose of the indescribably powerful opponent totally outside the conception of human reason, Wulong is every bit the repudiation of the sensuous, excessively violent Yujiro. He trains his potential competitors and socializes with his enemies. Sandrovich’s worst tendencies come out in Wulong revealing his ultimate goal; a goal that, if achieved, will mean Wulong will abandon the over-engineered conspiracy that is critical to Omega’s plot:

Shen Wulong is just looking for a good fight. In that sense, he is perhaps more similar to Yujiro, who fosters the growth of his son in service of a definitive showdown in which Baki uses all of his potential1. But Yujiro tries to wring the potential from Baki through various brutal and sadistic enterprises while Wulong is content to wait for his desired competitor to be presented. One can’t help but predict, based on Omega’s optimism, Wulong will ultimately be a cordial colleague and good-natured competitor rather than an imposing villain. I doubt whoever beats Wulong in the end will feel as “earned” as Superman defeating Goku in the eyes of a guy who wrote a 10,000 word forum post about why and how Superman would win.

I am probably much closer to Sandrovich’s ideal reader than the people invested in debates about which fictional character would win in a fight. I don’t really care who beats Wulong in the end as long as the fight looks cool (Daromeon’s responsibility) and Sandrovich can draw out some interesting character moments before, during, and after the fight. It’s possible Sandrovich has written himself into a corner with the spectacularity of his plot and the seemingly infinite power of Wulong; but I imagine he’ll be able to come up with some direction to take the story if he even bothers to continue it past Wulong’s inevitable defeat. I don’t think I mind Sandrovich’s naïve optimism he showcases in Omega, though. And as long as Daromeon keeps drawing well, I’ll keep reading.

Weekly Reading List

https://tachimanga.app/ — This application has changed my life. It has made it trivially easy for me to read my legally purchased digital manga and comic book files. I think I’ll share more details in a post exclusively for paid subs, but if you are technologically inclined and want to read manga, you should be able to get everything figured out following this link.

Judges’ Tower is one of my favorite ways to play Magic: the Gathering so I am always excited to see it represented in videos.

Event Calendar: The Lull of “Q4”

Didn’t add much here other than a few forthcoming movie releases. Got stuff I should add relevant to the Paradox audience? Let me know.

Until next time.

This is also a pretty common manga trope in various incarnations, whether the Yujiro-esque malevolence of Hisoka’s attitude toward Gon in Hunter x Hunter (1998) or the existential anguish and loneliness at the top explored in 100 Meters (2018).