Issue #406: One Bait After Another

Despite an uncharacteristically un-festive Noirvember, I got a chance to see Odds Against Tomorrow (1959) last night. It’s a great, great film, but with a very overt didactic message. In it, Earle Slater (Robert Ryan), Johnny Ingram (Harry Belafonte), and Dave Burke (Ed Begley) plan a heist of a small town bank. Burke, a disgraced police office, is the mastermind. The film focuses on Slater and Ingram, two characters who are juxtaposed against one another like Guy (Farley Granger) and Bruno (Robert Walker) in Strangers on a Train (1951). Robert Wise avails himself of repeating the same scene, first with Slater, then Ingram, as opposed to using Hitchcock’s cross-cut. The opening emphasizes their difference. Slater is rude, leaning toward desperate, and, critically, heinously racist. Ingram is charming and well put together. Burke sells to Ingram harder, yet Ingram is a tough sell. Burke says, “you don’t look like I could sell anything to you.” The pitch is the robbery, but Slater’s prejudices mean he won’t work with Ingram. Ingram has a more sympathetic objection, “That’s for junkies and joyboys. We’re people.”

The question of what one will or won’t do under the auspices of a law-abiding society is one of the film’s critical questions.

Most of the film’s runtime is dedicated not to the planning of the heist, but Ingram and Slater anguishing over whether or not to do it. When push comes to shove with Ingram’s debt, he decides to participate in the caper. His motivation is streaked with altruism as his daughter and ex-wife are threatened. Bacco (Will Kuluva) would make them casualties of Ingram’s gambling addiction.

Slater, on the other hand, is moved to throw his hat in with Ingram and Burke for reasons as confusing as they are offensive. He is humiliated by his girlfriend Lorry (Shelley Winters) paying his bills. Beyond the incomprehensible misogyny, meant I think to appear unsympathetic even to a late 50s audience, there is some genuine pathos in Slater’s fear that if he is unable to provide financially, Lorry will leave him.

Belafonte is stellar as Ingram. For the film’s first half-hour, he is the put-together functioning addict so often floating through these noir and heist films. The breakdown arrives at around that thirty minute mark, the disposition of a gambler much more in line with contemporary expectations of a man coming undone because of his compulsion.

Odds Against Tomorrow is not subtle in its opposition to racism and racial prejudice. And the film can drag at times with the overwrought drama of Ingram and Slater getting pushed further and further into desperation that will ultimately lead to disaster. But Belafonte is undeniable and Wise has an incredible eye for disorienting close-up shots and cinematic shootouts. For better or for worse, it is set apart from most film noir because of its humanism and socially responsible imperatives.

Oh yeah, I forgot to mention this past weekend was my birthday. Consider purchasing a paid sub in celebration.

Flipping All Night in Q-Up

Since last week, I’ve been playing a lot of Q-Up (2025), the latest from Everybody House Games. It is not a game that is easy to explain in a way that makes sense or does it justice. Developer Frank Lantz describes it as “start[ing] out as a simple clicker” and says it “should appeal to fans of Zachtronics-style engine-building puzzle games.” The discussion about the game on r/incremental_games is wide-ranging. Posters call it “an incremental/autobattler,” which is reasonably accurate. Steam achievements like “Reach Novice in less than 200 flips,” “Reach Anomaly without ever deranking,” and “Reach Novice in less than 3 hours” point to a roguelike gameplay loop that requires restarting the game from the beginning in order to meet the restriction criteria. But the game is really a roguelike-like, tying progression to the random selection of enhancements from a much larger pool that is associated with roguelikes but not actually a mechanic from Rogue (1980). I associate this mechanic most with Magic: the Gathering’s draft format. Q-Up combines the “drafting” idea of their randomly populated shops with deterministic skill acquisition based on a chosen class. Each playthrough with a given class will make all possible skill builds for that class available by level fifty. But the randomly appearing gear one finds, more or less likely to appear in one’s shop based on rarity, will dictate what configuration of skills are better or worse.

Playing Q-Up, I felt like I intuitively understood it, it “clicked,” before I could articulate the ins and outs of how to play to someone else. But there are also more and more layers that reveal themselves as you play different classes because they present different strengths and liabilities depending on when you win or lose a flip. Oh, right, I haven’t mentioned that yet: Q-Up is a game, ostensibly, about competitive coin flipping.

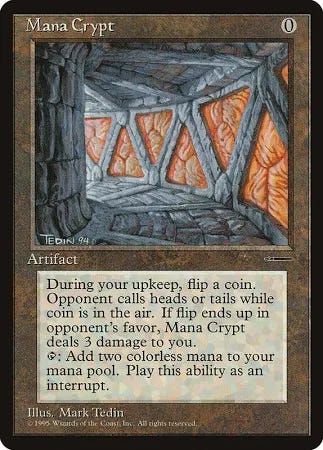

It really does involve coin flipping, so the outcome of a match is dictated by the outcome of best-of-five coin flipping where you and your teammates are randomly assigned the “Q” or “Up” side of the coin. I used to think flipping coins to resolve the upkeep trigger of Mana Crypt would be the pinnacle of coin flipping gameplay. But Q-Up is truly the most fun you can have while the force of digital gravity decides what face of the coin is against the ground.

Lantz describes Q-Up eloquently, “it’s not about winning or losing (the coin decides that) it’s about how fast you can make progress through the metagame[.]”

The metagame involves gaining ranks that are awarded based on accumulating Q, a point value that is either awarded or subtracted from your overall total based on the result of every flip. As far as I can tell, there are two methods of progressing:

Gain Q regardless of whether you win or lose the flip

Gain an amount of Q on one coin flip outcome that is significantly larger than the amount of Q you lose on the other outcome

I’ve reached “Novice,” Q-Up’s highest rank, using both strategies. And the amount of Q you gain is determined by the various class skills and gear you use, which modifies both your total Q gain and a multiplier that will apply to your Q — whether you are gaining or losing it. There’s a resemblance to Balatro (2024) in this arrangement of numbers. Indeed, I don’t think it would be unfair to describe the game as similar to Balatro where the hand you play is selected for you and there are only two possible hands. You want to maximize your result regardless of the random outcome that will dictate that result. The management of skills and gear will feel similar to choosing and ordering jokers.

As you rank up, the amount of Q you lose per lost flip increases. You could analogize this as the growing numeric wall you have to overcome in any incremental game. Sometimes it felt to me I would hit certain points in a playthrough where the increase in lost Q served the gameplay function of the “DPS check” style boss in an RPG.

Describing Q-Up is subordinate to the sublime experience of playing it. It is a really really good game. It is multiplayer, but largely asynchronous. Developer stik says, “You will be matchmade synchronously with other real humans that are playing at that time if they exist, but the actual playback of the match is not synchronous once the matchmaking is complete.” The game has a competitive veneer, but is mostly cooperative until you reach that final Novice rank. Players on your team will, on average, have a minimal impact on your results, but certain builds and planning among an established team can mean much higher Q gain for everyone.

Q-Up is also funny, satirizing esports, corporate office life, and gaming culture. Many of the jokes are also thought provoking and relate to the game’s themes. Because the game presents first a puzzle of what it even is, the player will always ask “where is the game here?” before doing anything else. Q-Up continues to explore the nature of gaming with both its humor and mechanics. This is at least reasonably thought through by the developers. As Lantz says:

In a way, attention is the key skill of Q-UP. There’s a lot of things you can look at, and they all matter in different ways. How are my items working? When is this skill going off? How much of this stuff am I generating? Is that thing I tried working? And they all kind of happen at the same time. It’s a lot of valuable data, and you have to decide where to look.

Another place you can look is the emails, delivered to you by NPCs, where “gameplay” significance is minimal, but there is plenty of amusement and intrigue to be had.

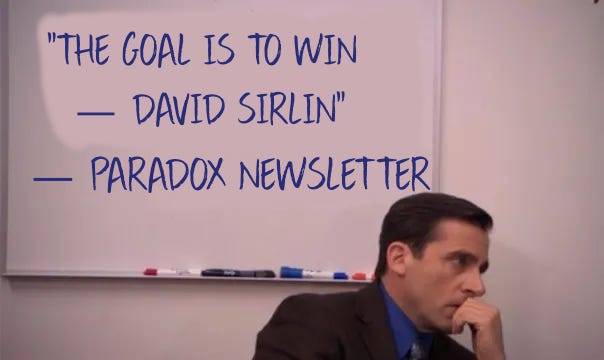

The game combined with Lantz’s excellent writing about it for his newsletter Donkeyspace makes clear that we are dealing with a team that knows ball. I even got to choose a David Sirlin quotation for my email signature: “The goal is to win.” Gaming is serious business for Everybody House Games.

My recommendation of Q-Up is totally unqualified. You should play it if you love games. You should play it if you hate games. You should just play it. It presents no barriers based on one’s dexterity. Q-Up is a good, old-fashioned thinker. And it’s a great game to play while shooting the shit with your friends.

You can find me in the Novice queues.

A Unified Theory of Bait

Somehow, I don’t think I’ve ever shared this mantra from my friend Cory in the pages of the newsletter:

DO NOT CLICK THE BAD CONTENT

DO NOT READ THE BAD CONTENT

DO NOT SHARE THE BAD CONTENT

The meaning may be obvious here, but I feel compelled to (over)explain how I have internalized this advice. Calling works of art “content” is odious to me, and that is not the meaning here. “Content” here means social media posts, blog entries, articles, headlines, the stuff I think most people encounter when “scrolling.” Adding the descriptor of “bad” is all-encompassing, it may mean poor quality, rage-inducing, whatever. But this philosophy feels most applicable to that which one might call “bait,” or “trolling,” the kind of material that is presented precisely to aggravate or shock and farm interaction. With the introduction of payment for viral twitter posts, this kind of posting has reached a profoundly cynical extreme. People will pose questions that appear to be rhetorical with no obvious answer or share a photo with a caption that does not draw attention to some obvious, shocking feature. The responses will then ask what the question is trying to suggest or something like “is nobody going to point out this ridiculous detail in their photo?”

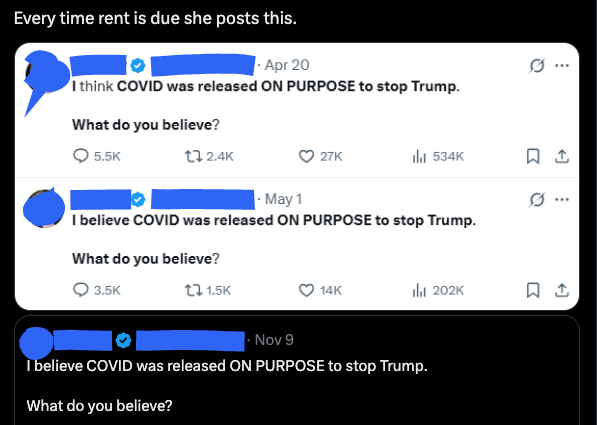

These patterns have become so obvious on twitter, posts that have the quality of “engagement farming” or “bait” appear to coincide with the first of the month.

Verified checkmark, controversial or confusing post, and close to the turning of the month have become a reliable heuristic for sussing out bait. Because twitter has introduced payment for viral tweets for those who are verified, the incentives are clear. Pay for verification, post something that gets a lot of interaction, and get paid.

These incentives are new to twitter, but not new to the economy of the written word. “Bait” and “trolling” have existed for just about as long as published writing. Though the situation on twitter shows how individuals might be implicated in enriching themselves in this way, posting something they do not believe for the sake of engagement, there are many examples of editors or editorial boards choosing to spotlight writing that they know will incense their audience. Bait, then, is not always authored in bad faith, though it will nearly always be presented in bad faith.

Take, for instance, the conflict between Joyce A. Joyce and Henry Louis Gates Jr. in the pages of New Literary History, a reputable academic journal. In 1987, NLH published “The Black Canon” by Joyce which took aim at established critics Gates and Houston A. Baker Jr. The editorial board invited Baker to respond, but his “In Dubious Battle” more or less dismissed Joyce. Gates, on the other hand, engaged with Joyce’s work a bit more rigorously in “‘What’s Love Got to Do with It?”: Critical Theory, Integrity, and the Black Idiom.” I first got assigned these three readings as an advanced undergraduate and read them again in my first year of graduate school, along with Joyce’s reply “Who the Cap Fit.” Joyce was at the time and remains a tremendous scholar in her own right, but in 1987 there was an unquestionable imbalance in the profile of Joyce and Gates. Nonetheless, NLH decided to stage and broadcast this ugly conflict. Gates’s reply needed a sterner editorial hand, Baker’s probably should not have been published.

There were methodological problems, too, in Joyce’s original argument that I have to hope would have been clear to peer reviewers of the piece and might have been corrected before they were seized upon by Gates. My perception of NLH forever changed for their brief foray into turning their pages into a site of an internecine, personal squabble among literary critics writing in a way that contravened the codes of collegiality for the discipline, especially in the case of the senior scholars “punching down.” Joyce and Gates’s dispute has had a profound impact on literary criticism and the lines of argument each pursue are critical to how the discipline has developed. I want to emphasize these are great works of thought in the field. Maybe their antagonistic quality is a necessary part of developing these thoughts. But, without question, NLH knew what they were doing. They presented the shocking conflict to their benefit, instrumentalizing the earnest urgency evident in the writing of Joyce and Gates.

This episode in NLH is not exactly understudied, but I would like to give it more sustained consideration at a later date. Today it is an illustrative example of the fact that “bait” can emerge from positioning genuine emotion, deeply held convictions, and reasonable ideas in a certain context. It also exemplifies how benefitting from that which will aggravate and polarize an audience is an enduring part of publishing and cuts across all venues of publication. Editors are incentivized to hold back critique and instead throw their writers to the dogs for the sake of frenzied reaction. I feel sincerely bad for writers who publish something they believe will be inoffensive or well-received that an editor knows will occasion an aggressive response.

Regardless of where or how the bait appears, the imperative is the same. Don’t click it, don’t read it, don’t share it. Doing any of these things enriches the person operating in bad faith (sometimes author, sometimes editor/publication) and divests the person succumbing to the bait of time and energy.

“Our lives are like houses build on foundations of sand. One strong wind and all is gone.”

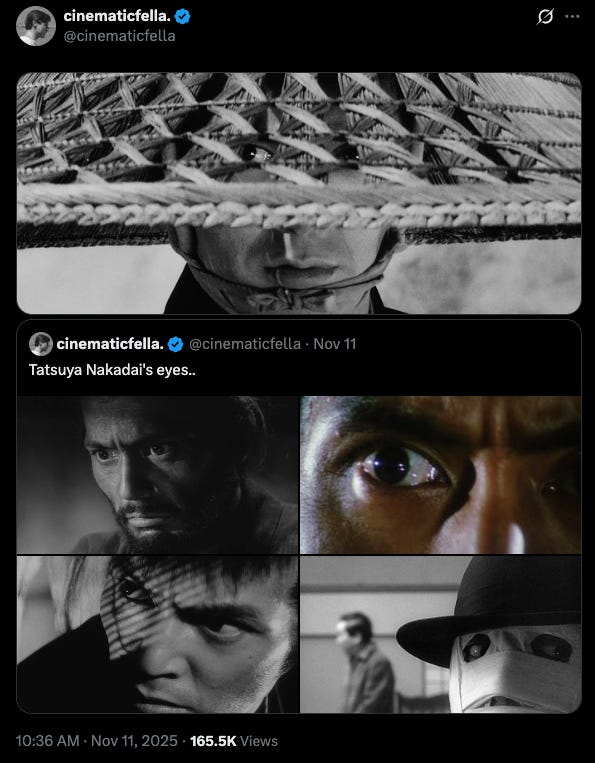

Tatsuya Nakadai died of pneumonia on November 8th, but his death was reported to the world on the 11th. At 92, Nakadai was an incomparable titan within the art form of cinema. He worked with the greatest directors of Japanese film, Kihachi Okamoto, Masaki Kobayashi, Hideo Gosha, Akira Kurosawa, and Mikio Naruse. And he worked with them a lot, five films with Naruse, six with Kurosawa, ten with Gosha, eleven with Kobayashi, and thirteen with Okamoto. Ridiculous.

It’s no accident that his collaboration with these filmmakers was so enduring. He worked with Kurosawa across a twenty-year span, with Gosha and Kobayashi in four different decades, and his prolific collaboration with Okamoto began in 58 and ended in 2001: almost half a century. With Okamoto, he made what I believe to be one of the best films of all time: The Sword of Doom (1966) adapted from Kaizan Nakazato’s novel series.

Okamoto’s own career and U.S. reception is inextricably tied to his work with Nakadai in films like Kill! (1968) (another of my favorites), Japan’s Longest Day (1967), and Sugata Sanshiro (1977).

Kobayashi directed Nakadai’s most celebrated film, Harakiri (1962), along with The Human Condition series and Kwaidan (1964).

Even as Harakiri may be hailed as the greatest Nakadai performance and the film for which I think he is most well-known, his work with Kurosawa, front to back, is epoch defining. He co-starred across Toshiro Mifune in Yojimbo (1961), Sanjuro (1962), and High and Low (1963).

The happy production accident of Mifune and Nakadai’s final duel in Sanjuro is the creation myth of samurai film.

Kagemusha (1980) and Ran (1985), Nakadai’s ascendency to leading man in front of Kurosawa’s camera, define Kurosawa’s late style and are among the greatest artistic triumphs of human history.

There is no higher stakes filming scenario than Kurosawa’s conflagration in Ran, where Nakadai descends the stairs of a burning castle that Kurosawa was actually setting on fire.

The video above is youtube guy Lextorias quoting Akira Kurosawa as Kurosawa is, in turn, quoted in Stuart Galbraith’s The Emperor and the Wolf (2002)

Nakadai’s importance to me should be already obvious from how often he and his films have come up in the newsletter. To this point, I’ve linked to four essays about Nakadai’s films. I made a case for Nakadai as the GOAT just four months ago. I even wrote about Harakiri in connection with my marriage last year.

So, to say I am gutted by his passing would be an understatement. I think what is worse is just how obscure he is among “normal people,” people who are not film enthusiasts, when his prodigious talent and singular contribution to the medium is indisputable. There is a silver lining to this state of affairs, though. It means there is a great deal of pleasure ahead for the many who discover Nakadai and see his work for the first time. And, indeed, even for us, devoted fans, who will watch his work again and again and discover something each time.

Critics and commentators often compare Nakadai to Mifune, who both stand as paragons of Japanese cinema to the U.S. audience. The comparisons are not unwarranted. They got their start within six years of each other. Mifune worked more or less up until his death in 1995, like Nakadai whose most recent credit is in 2020.

But there is something about Nakadai that will put him above other actors for me, including my perennial favorite Denzel Washington. Mifune, like many stars, are always unmistakably themselves despite their convincing, compelling performances. Nakadai, on the other hand, transforms. The way he embodies is roles is shocking. There is a radical incongruity between, say, Tsugumoto Hanshirō in Harakiri and Ryunosuke Tsukue in The Sword of Doom, roles separated by only four years. Nakadai’s unmistakable characteristics are buried beneath a total metamorphosis: his eyes, his laugh that Harakiri made famous.

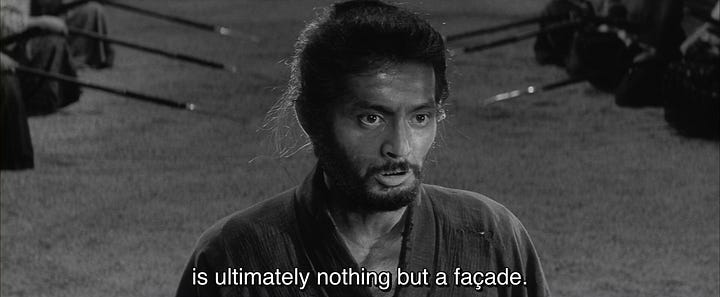

In that career-defining role as Tsugumo, Nakadai plays a samurai who confronts the hypocrisy of bushido in the controlled environment of the castle courtyard. Harakiri, unquestionably a violent film, unfolds in an unfamiliar setting for samurai fiction. Tsugumo embarrasses the proud samurai who forced his son-in-law (Akira Ishihama) to disembowel with a bamboo sword. Harakiri manages to be one of the most incisive critiques of the moral code of a era long past, but also a timeless moral tale about the sin of pride.

He says, as I title this piece, “Our lives are like houses build on foundations of sand. One strong wind and all is gone.”

Kobayashi, the director who birthed Nakadai as an actor, draws the tension of Harakiri taut as Tsugumo slowly reveals the purpose of his presence in the Iyi courtyard. To be disemboweled? Yes, but also to place in front of the Iyi their own failure to live up to bushido along with his entrails. Each samurai that Tsugumo has defeated in combat has hidden their disgraceful failure, the severing of their top-knot by Tsugumo, feigning illness to remain unseen. Nakadai’s surprise, Tsugumo knowing these short-haired samurai will not be showing up to work, comes across with the perfect balance of genuine surprise and knowing certainty that those who judged his son-in-law so harshly cannot turn that exacting gaze on themselves.

Nakadai’s own commitment to the vocation of acting is not so flimsy. The monument of his work cannot be effaced by even the harshest conditions.

Weekly Reading List

Frank Lantz has got a certified fan in me, which should be obvious from my writing about Q-Up. Here, he explores SET, a really fun card game I played in elementary school. His account of SET’s design reflects a tendency I admire in writing: exploring a niche topic but ultimately relating it to something more human.

A quick, informative breakdown of the samples in “I Wish.”

The best ever.

Event Calendar: Ethan Hawke

My event calendar is looking a little thin. This week, I added a series of Ethan Hawke films the Coolidge is showing in advance of giving him some kind of award. Training Day (2001) and First Reformed (2017) are among my favorite films of all time, so you can bet I’ll be coming through.

Until next time.