Issue #397: How Do You Say 'Unconscious' in Japanese?

The Music League continues unabated. With all the promised chaos, the “Free Parking” prompt inspired a wide range of submissions.

Whatever algorithm generates the playlist has impressed me. Even if it’s totally random, Anti Cimex is a good note to start on. The nature of the permissive prompt made the end result diverse. Some pockets of hardcore, “Afro-jazz,” commonly sampled R&B, some heavy hitters of rock (by that I mean Ween and Weird Al), and no less than two songs in Portugues.

Both for my own sanity in song selection and for playlist cohesion, I like more restrictive prompts better. I probably won’t use this one again if we run another one of these.

I think we will deliver a reward worth more than those from the various entertainment academies of the United States. The Emmys, as always, are a scam. My relationship to this award show is nothing like the Oscars. I never watch it. This year, against my better judgment, I did. I watched with hope in my heart that The Rehearsal (2022) would be recognized.

Regrettably, it was snubbed. Severance (2022) took home two supporting actor Emmys, but was otherwise outdone by The Pitt (2025).

Another frequent newsletter topic, The White Lotus (2021), was denied a single statue. Rough stuff.

Adolescence (2025) had such a remarkable showing, I decided to give the first episode a try. It is only four episodes overall, so I’ll watch the whole thing. But so far, I’m not impressed. Every episode is one take, but it comes across more like a gimmick. There are a lot of facial close-ups so people can move around and set up the next scene. Rather than “immersive,” I find this kind of unnecessary flourish to be “immersion breaking.” Not that a show is better or worse to the degree it does or doesn’t draw attention to itself. But, this does draw attention to the artificiality of the form in a way that I don’t think is intended. So far, it’s a big miss.

Strange Harvest and Horror Mockumentary

There are some as-yet unrefined gems of insight related to the idea of the texts produced for the “second screen.” Ralph Jones articulates this phenomenon in relation to Netflix, suggesting that production companies creating TV shows for the streamer deliberately engineer them to be watched in the background while someone scrolls on a smartphone. It’s not a completely new idea: I think of Tim Cruz’s The Final Rose (2022) where his protagonist watches his fictional facsimile of The Bachelor while folding laundry.

Theory1 aside, there are exigent formal questions. Such works that aim to play without the audience’s full attention should be dialogue heavy, perhaps podcast-esque, limiting the visual interest. The documentary, generally, is well-suited to this kind of construction. If the primary image on screen is a person seated, speaking, oriented toward the camera in the exact same way, the viewing experience is not the same as other kinds of visual art. This brings me to Stuart Ortiz’s Strange Harvest (2025), a horror film that has all the formal trappings of something suited for the “second screen” but is impossible to look away from.

The film primarily unfolds as an interview of two detectives, Joe Kirby (Peter Zizzo) and Alexis Taylor (Terri Apple) who are investigating the ritualistic, serial murders of Mr. Shiny (Jessee J. Clarkson). This horror “mockumentary” comes from the mold of The Conspiracy (2012), The Sacrament (2013), and Noroi (2005) which present themselves as completed texts rather than an assemblage of discovered recordings, more typical in a found footage premise. Strange Harvest is polished, using all the flourishes of true crime documentary and restricting itself to the presentation of “real” footage as opposed to re-enactments.

Even as the film is structured like other mockumentary horror films, it is most similar to Koji Shiraishi’s Occult (2009), a more conventional found footage horror. Like Shiraishi in that film, Ortiz hides some of the most shocking cosmic horror behind distorted camera footage with the alibi of a technological problem. Likewise, both Strange Harvest and Occult connect mystical and cosmic horror.

Ortiz is best known for Grave Encounters (2011), but Strange Harvest is a much, much better film. Aside from the Shiraishi influence, there is also the obvious pastiche of Fincher’s Zodiac (2007), with Ortiz’s film drawing attention to a comparison between Mr. Shiny and the Zodiac Killer only minutes before mentioning issues with jurisdictional alignment in serial murder cases where each incident occurs in a different county or city.

Strange Harvest is not widely available, but it is worth seeking out for genre fans. It’s certain to be one of the most underrated horror films of the year.

Shinsō-shinri and Muishiki in Kamen Rider ZEZTZ

Kamen Rider (1971) is usually a children’s show, though occasionally Toei releases “elevated” Kamen Rider works for adults.

Kamen Rider ZEZTZ (2025), the new series for the Super Hero Time programming block on TV Asahi, is not one of these. However, it is historic for the franchise. It is the first series, ever, to be simultaneously available in the United States. Shout! Studios specially branded youtube channel is broadcasting the show weekly in the US, Canada, UK, Australia, and New Zealand with English subtitles. This is huge.

So far, the production value has been really good. The Shout! Studios localization is unusually detailed, translating every relevant bit of text on the screen.

Sign and text translations were really common in anime localizations in the 2000s, but I barely see them now. If they’re translated, they are usually squeezed into the subtitles with the dialogue at the bottom of the frame rather than edited on top of the written Japanese text. As a viewer, I appreciate this tremendously. It shows me that Shout! Studios and Toei are really putting in significant effort for this long overdue attempt at making Kamen Rider legally available to English speakers as it airs. And the visual gags from ZEZTZ have been funny enough that the trouble to subtitle them is worth it.

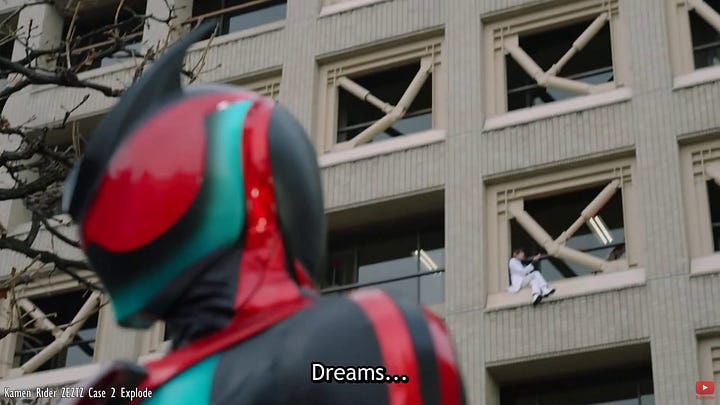

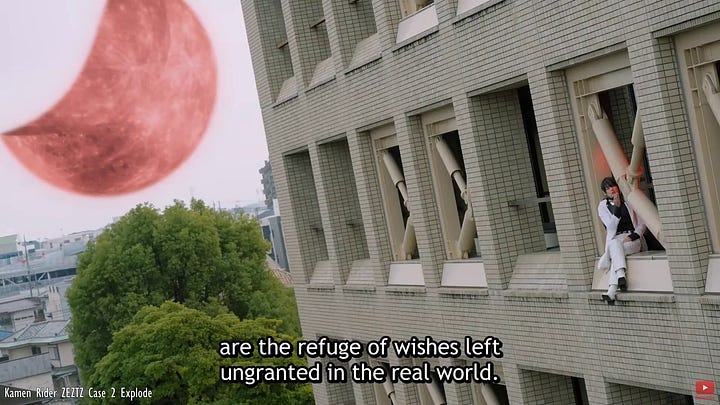

We are two episodes in. The most recent, “Explode,” more firmly establishes some interesting conventions for the show. First, the villains are a little bit shocking. They are creatures called Nightmares, who inhabit dreams and threaten to steal the corporeal body of those who dream them. Speaking of the imperiled dreamers, they cause the Nightmare to form according to their deeply held wishes — following Freud’s maxim from The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), “a dream is the fulfilment of a wish” (147).

The revelation that the dreamer brings their threatening Nightmare into existence through their unfulfilled wishes is the eleventh-hour twist of “Explode.” It’s worth diving into some of the specific terminology here as the show’s themes relate to psychoanalytic theory. Despite the evident Freudian influence, ZEZTZ’s script is not using the terminology consistent with Japanese translations of Freud, Lacan, or other Japanese psychoanalytic theorists. The show repeatedly refers to the “subconscious,” a translation of shinsō-shinri/深層心理, though you might translate this literally as something like “deep psychology,” or “the depths of the mind.” The specific, topological dimension of this phrasing is what makes the subconscious translation make sense. This follows the pattern of colloquial English, too, where “subconscious” is often used when the intention is to refer to the Freudian unconscious. “Subconscious” or shinsō-shinri are used in pop-psychology writing and colloquial conversation in both the U.S. and Japan. On the other hand, the Japanese term for the specific, psychoanalytic unconscious, the one used by Japanese scholars, is muishiki/無意識.

Not that I expect ZEZTZ to be rigid and exacting in its use of psychoanalytic terms, but another dimension of confusion here is this topological quality to the dreams that produce the Nightmare monsters. Instead of the desire emerging from the unconscious, ZEZTZ seems to suggest that the desires in question are repressed, meaning the restriction of a conscious thought into the unconscious. In the episode, the unfulfilled wish in question creates a “Bomber,” a villain who seems to allude to acts of terrorism using explosives.

The bomber targets a police station, meaning the dreamer, Tetsuya Fujimi (Kenta Mishima), has in some obscure way wished for the destruction of his own place of employment.

I’m curious to see how the show, as the episodes proceed, will resolve this radically destructive dream with a character who we have, until now, seen as a hero. One simple avenue would be to introduce it as an idle, indeed, repressed thought from his dissatisfaction at his career progression. Another more interesting approach would be to truly embrace the logic of Freudian dream interpretation, where his wish is transformed into a certain form — an explosion that destroys the police station — through the mechanism of the unconscious. Though we probably won’t hear the word muishiki spoken at any point in the show’s run.

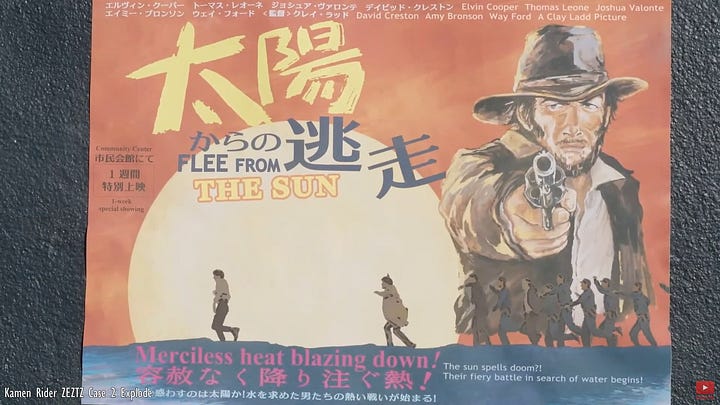

The previous episode had a Nightmare just as scandalizing, transforming the spectre of gun violence (essentially non-existent in Japan) into a monster that Kamen Rider can beat up. ZEZTZ also draws inspiration from classic spy and western cinema, as well as sci-fi procedurals like X-Files (1993). I think it all comes together rather nicely.

Baku Yorozu is the protagonist, played by Ryutaro Imai in his first major acting role. Imai gets to show off some range as Yorozu. He spends his waking life as a goofy guy, typical of late Heisei and Reiwa era Riders. But, in his dreams, he works for a spy agency and adopts a cool, disaffected demeanor. That demeanor comes through as part of his Rider transformation. As the real, waking life and the dream life where he primarily fights the antagonists begin to coalesce, so too do his personalities.

The aforementioned police officer, Fujimi, and his partner, Nasuka Nagumo (Rina Onuki) play out an exaggerated Mulder (David Duchovny) and Scully (Gillian Anderson) dynamic with some decent gags. That comes together with Yorozu’s Mission: Impossible dream life and the Persona 5 (2016) premise of entering people’s dreams to save them from threatening thoughts.

Week-to-week Super Hero Time Kamen Rider series aren’t for everyone. But the risk is low. Just twenty-three minutes on youtube to see if it’s something you might enjoy. I would really like to see this series be successful in its international broadcast. It streams 7:30 PM Pacific, 10:30 PM Eastern on the TokuSHOUTsu youtube channel.

Weekly Reading List

I hate relegating Lacan’s most recently published (in English) seminar to the “Weekly Reading List.” My preference would be to produce a substantial, considered analysis of the seminar. High volume of words, high volume of theoretical precision, etc, etc. But I am doing that for my conference paper, mentioned below. Thus, my academic requirement satisfied, I can gloss this seminar more superficially.

I’ve been drawing from this seminar a bit for the newsletter. It addresses ideas having to do with the function of the signifier and discourse (“the signifier is identical to the very status of semblance” [7]), the non-relation (“Nothing allows us to abstract the definitions of man and woman from our complete experience of speech” [23]), his opposition to idealism (“we know things by means of an apparatus known as discourse — the Idea is ruled out” [19]), the merit of Voltaire (“of course, no one [reads his work] anymore, which is dumb as it contains plenty of things” [44]), and plenty more. The seminar’s second chapter is my favorite treatment by Lacan of sexual difference.

The signifier’s status as semblant is the main event, as one might infer from the title. As main events go, Lacan defines his thinking in this period (1971) as an elaboration of Lévi-Strauss and Barthes. Ultimately, the signifier’s status as semblant is precisely why the signifier is opposed to its referent, “Where the subject is represented, he is absent. That is why he finds himself divided in this way, being represented all the same” (2). While Lacan outlines a structure, it is far from rigid. Lacan also outlines the many interruptions to the signifier’s function endemic to psychic life. These interruptions move the signifier out of the way, or evacuate it of meaning such that it is not a semblance precisely because it is nothing at all, “At the limits of discourse, insofar as discourse strives to hold that semblance together, some real occurs from time to time” (24).

Some of the press for Highest 2 Lowest (2025) has been pretty bizarre, but I enjoyed this discussion between Lee and Washington.

The problem with the Music League is one is restricted to what is available on Spotify. In our first round of covers, I couldn’t help but think of one of my favorites: Otomo Yoshihide’s version of Eric Dolphy’s Out to Lunch (1964). Yoshihide’s version was released in 2005, following an extremely prolific career dating back to the late 80s. He is best known for his contributions to Ground Zero through the 90s, but I was introduced to him through his MC Hellshit & DJ Carhouse project, a collaboration with Yamantaka Eye. Yoshihide has plenty of experience as a jazz player, too, first in Otomo Yoshihide’s New Jazz Quintet and then in Otomo Yoshihide’s New Jazz Ensemble. Finally, for the Out to Lunch cover record (a reinterpretation?), he led Otomo Yoshihide’s New Jazz Orchestra.

Dolphy’s original version is already pretty bizarre, so Yoshihide’s experimental gloss is quite extreme. He brings distorted, screeching guitar to the background of “Hat and Beard” with an aggressive, dissonant version of the original melody. Dolphy’s clarinet intro on “Something Sweet, Something Tender” is just slightly off from something you could excerpt and use as the score for an introduction of a femme fatale in a film noir. Yoshihide’s version is just too twisted, bringing in the off-kilter clarinet screeches even sooner. He has like fifteen people, way more than Dolphy’s band. I think Alfred Harth is playing the clarinet for Yoshihide, renowned for his many contributions to underground and avant-garde music.

When I first heard it, I felt like Yoshihide’s version really drew something out of the Dolphy original, helping me appreciate both. It’s like what Hideo Kojima says about the Project Itoh novelization of Metal Gear Solid: Guns of the Patriots (2008), “Project Itoh already dwells inside my game. Itoh-san took this game, retold it, and handed me back his own Metal Gear Solid.”

Event Calendar: Paradox Live! at Psychology & The Other

The Psychology & the Other conference is this weekend, where I will be presenting on Cure (1997). I’m pretty happy with how that has all come together. I already outlined some of the sessions I am excited for previously, but you can find them listed below.

Until next time.

Mark Fisher theorizes an analogue to the “second screen” idea as a “sensation-stimulation matrix,” though I find his argument to be lacking in precision and insight (Capitalist Realism 24).